|

January 2022 Nearly two years ago, we independently applied to the SciArt Initiative’s Bridge Residency program. A bridge connects two places, spaces, ideas, people, and The Bridge is intended to connect artists and scientists who together might “generate new ideas and provide new perspectives which can lead to innovation in existing fields or the creation of new ones.” Through weekly zoom meetings and our series of nine blog posts, we used The Bridge and the opportunity for bridging that it created to introduce each other to our different perspectives and ideas about ecology, photography, and woodworking while sharing fragments of our day-to-day lives. What we were doing at the same time, albeit less explicitly, was developing a shared language that we could use together to build a friendship and to develop and instantiate creative and collaborative projects. In hindsight, we can say that we started out our residency on different sides of a bridge but ended it at the beginning of another. Now, we are crossing this new bridge together from familiar ground into new, creative territory. In this post, we sum up where we’ve gotten to in the year since the formal end of our residency and reflect on how it has changed our creative, scientific, and technical practices as we continue to engage in collaborative work. Where we’ve been The theme that emerged from our time spent in/on The Bridge focuses on a non-anthropocentric aesthetic: decentering humans from their centrality in defining beauty and the picturesque, a consideration of how other organisms “see” and understand visible characteristics of the world around them, and how this consideration might expand our understanding and conceptions of our own aesthetics. We have been honing this theme and developing projects around different aspects of it through photography, workshops, and creative and technical writing. By the end of our residency, we had applied to Art Explora for a Duo Residency at Montmartre, submitted proposals for workshops at the 2021 Borrowed Time event in the UK and the 2021 CICA New Media Art Conference in South Korea, and submitted an abstract to present at the 2021 biennial conference of the International institute of Applied Aesthetics (IIAA). Of these first four submissions, we batted .500: the CICA workshop and the IIAA paper (both presented virtually because of ongoing effects of COVID-19). And we had similar success with an abstract we submitted—and the paper we subsequently presented—at the 2021 annual meeting (also virtual) of the International Visual Literacy Association (IVLA). But we struck out with Art Explora, Borrowed Time, and other residences (Tusen Takk, Loghaven) and opportunities for exhibitions (COAL, PhotoPlace Gallery’s In Celebration of Trees) for which we subsequently applied. Whereas grant competitions in the sciences have a success rate of 10–30%, most of the residencies and exhibition opportunities we applied for received > 900 applications for a single slot—a success rate of about 0.1%. But the most fun and most productive work was done in the field working together. As travel restrictions eased in the fall, we took a break from our continuing weekly zoom meetings and got together in person to start developing these ideas in practice. In late October, we spent 10 wonderful days in the Great Basin region of the southwest US, photographing bristlecone pines (fig .1)—the oldest individual organisms on Earth—and the extreme, high-elevation landscapes in which these trees live, at Great Basin National Park (in eastern Nevada) and the Inyo National Forest (in southeastern California). At dozens of locations, we photographed the identical trees or scenes in digital color and infra-red, analogue ultraviolet (film), and with glass plates using an emulsion comparable to what would have been used in the 19th century. This field excursion was followed up with a week of developing and scanning the glass plates and 4×5᳓ film negatives, organizing hundreds of digital images, and additional technical production work at the University of Toledo, where Eric is an Assistant Professor of Art and Aaron was the first Axon Labs Creative Artist-in-Residence. Where we’re going

After more than a year of working together, we’ve developed a theme and a set of ideas that serves as the foundation for our creative and technical work. We are sieving through the large collection of analogue and digital images that we have accumulated and creating a portfolio of work that we can develop into exhibitions and use to clearly illustrate our written work. While we are waiting for editorial decisions on a pair of submitted papers, we are writing additional ones, submitting abstracts for conferences, and artwork for exhibitions. We look forward to continuing to expand on our existing ideas, evolve new ones, and create new work.

0 Comments

Eric & Aaron

For our last blog posting of this fantastic 18-week Bridge Residency in sci/art, we thought that rather than write separate blog posts that we’d write a single post as a dialogue about our experience and where we hope to go from here. We talk about five topics. What did we expect from the residency? AME: I don’t have a copy of my application to the residency, but I probably typed in something like this into the description box: I would like to work with a creative artist to learn more about how to integrate photography and sculpture with ecological theory to effectively envision, illustrate, enact, and communicate the expected and unexpected consequences of manipulating the world around us as we create novel ecosystems. And in my first blog post, I wrote that I see it [the residency] as a great opportunity to work with Eric (and perhaps others in this cohort) to explore new ideas, pick up on some simmering ideas in new contexts, and walk a different path from my ‘normal’ work as a scientist and academic administrator. ERZ: When I applied, I hoped I could extend the interdisciplinarily-informed work I was already making into new areas, and that happened almost immediately in our collaboration. I also expected to be paired with someone else who was equally interested in collaboration, and I am pleased that I got that and more, specifically - a partner who is already quite experienced in working with other practitioners inside and outside his field. AME: It’s easy to lose track of expectations, but on reflection, I feel there’s been a good match between what I expected from the Bridge and what I learned and accomplished over the last four months. ERZ: I also think, looking back, that when I applied, I was interested in seeing how another person works in a different discipline. Many of the things I do (photography, woodworking, teaching) function as some balance of observation and physical understanding, then repetition with reflection. I have found that I learn quite a bit more from others when I am unfamiliar with what they do, and I have certainly learned quite a bit in this short time working with Aaron. What have we learned? AME: I learned a lot about photography, especially its history and digital post-processing techniques. Talking with Eric about how to make better panoramas, from paying attention to leveling of the camera for each shot to tips and tricks in Photoshop has led me to think much more clearly about a photographic form I’ve used before not only for photographing scenery but also for collecting visual data about forest dynamics through time. Eric and I were constantly looking out for interesting things to read, and one of the most influential for me was Hagi Kenaan’s new book, Photography and its Shadow. It brings together themes from the history and cultural siting of photography, aesthetics, and existentialist, phenomenologist, and perspectivist philosophies. One reading of it is clearly not enough! I also thought a lot about how ecologists (and other scientists) use photographs primarily for documentation. Even though scientists have many photo contests that emphasize aesthetics, post-processing is frowned upon if not outright forbidden. Although such proscriptions certainly make sense when photographs are themselves data objects, the disavowal of creative post-processing places science-based photography firmly outside of the realm of photography-as-art. I’ve come to think that’s not a useful stance for sci/art collaborations that use photography as a medium. ERZ: I learned quite a bit about research forests, Hemlock trees, and the surveillance of these research forests and our world’s ecosystems. I thought about the “truthfulness” of images in the context of science even more than I previously had, which was quite helpful, as it informed the teaching of my History of Photography course in the Fall semester, during the start of our collaboration. One of the many recurring topics in our conversations around photography and ecology is the contradiction Aaron pointed out between the permanence of a photograph (at least to us as mortal human observers) and the persistence of change in natural systems. This tension informed the images I have made and posted to this blog, and continues to generate thought and experimentation with images of forests. I’ve also learned more about the collaborative process. As an artist, collaborations are not typical, and there are not many understood structures or methods for such things. I have worked in collaborative ways before, but not in a way where the collaboration started from a pairing up that was out of my hands. How did the residency change our practice? ERZ: I think in the aspects that I could conceivably measure in my practice, what has changed might be better examined as a shift in perspective, or a reinforcement of previously held values that needed deeper exploration. For example, I’ve gained a better understanding of the complexity of ecological systems, and the issues involved in their representation. As a result, I’ve been thinking less about the “now” of my practice, and more about the long-term, or perhaps even the full term of it; something that better echoes lessons learned from observing ecological dynamics instead of just other artists working in studios. AME: Several years ago David Buckley Borden and I wrote about how our sci/art collaboration affected my scientific research and practice. We wrote then - and still would assert that - major breakthroughs or innovations from art-science collaborations are more likely to be the exception than the rule. But we also wrote that sci/art collaborations provide new insights and skills and open up new avenues for creativity. Working with Eric has certainly given me many new insights and helped me develop new skills, and has both of us thinking about what projects we can pursue together. In my own scientific work, thinking more about photography of science is making me much more aware of how much my colleagues and I depend on photo-documentation without considering how our assumptions about it affect the science that we do. As with new insights afforded by my previous sci/art projects, the effects of this residency and associated projects will take time to become manifest. What have we accomplished? AME: Most importantly, I’ve found a new friend and collaborator. I successfully created panoramas in Photoshop and managed to restore to working order on a Windows 10 computer Canon’s 20-year-old (and no longer supported) PhotoStitch software to rescue me from Photoshop’s inability to automatically create a panorama from nearly 100 images. ERZ: I also think the most important accomplishment of this residency has been the new friendship and the great collaboration. For myself, I made images that are not yet visually successful, but are becoming more conceptually successful. I think this way of working is important - to work from an idea that may not be possible, and try to make it work while engaging an expert in the study of the thing being photographed, in this case forests. Together: We wrote nine blog posts (mostly on time) and have accumulated piles of digital images to sift through. We came up with concepts, sketches, and applications for workshops, exhibitions, and installations, of which some have been submitted (one accepted, one declined) and others are still pending. What’s next on our horizon? Together: We have a lot to look forward to that will enable us to continue our collaborative work. One of our workshop/exhibition proposals has been accepted for presentation in June at the 2021 CICA New Media Art Conference in South Korea. We hope that travel is possible by then, but if not, we will be able to participate in the conference virtually. We also have submitted a similar proposal for a workshop at the November 2021 Borrowed Time summit in England and an abstract for a paper on using photography to envision an ecological and non-anthropocentric aesthetic for the June 2021 IIAA 14th International Conference in Finland. Eric Today I was able to test out the linear tripod setup to see if the results for my panoramas would be better than the old method of moving the tripod by hand and guessing where the next frame should be. Let’s just say the results were mixed. The mechanics of the setup worked just fine—I attached my tripod quick release mounts to a 2x6 I had, and I then took it out to the same small pond near the Maumee river I photographed two weeks ago. When I get to the spot I’m interested in, it’s easy to extend the legs of the tripods, attach the board, and then level it up. Framing a view is easier with this apparatus because I can move the camera back and forth along the axis I’m making images from, and start to understand better what my final image will look like. I also have much more confidence that I won’t miss a frame this way. To take the image, I started on the left side and made the camera’s back (and therefore the image sensor) parallel to the board. I then took a series of roughly 10 images at different focusing distances before moving to each next framing position, to the right. I moved the camera about 6” each time, roughly the width of the camera body, which gave me around 50% frame overlap from one image to the next. The results in the field seemed to be much better, but when I got home to process the images, I realized that I had made a few choices that would result in a poorer image overall. The first issue was a determination to stay with a low ISO rating - this in itself was not a problem, it always results in an image with less noise, but it forced me to sacrifice by aperture opening (f/5.6 in this case), which made focus stacking very hard on Photoshop, giving me far more blurring than last time. Additionally, I kept my shutter speed low, which allowed the slight breeze to move some of the branches around, blurring information further. Nonetheless, I processed the image and stacked it together as you can see below (the preceding blog post’s image is just below this week’s for reference.) I think that this setup will work better in additional tries, if I can avoid the rain and sleet that has been falling lately, I’ll make some more trial images this week. I can easily bump up my ISO sensitivity rating to gain a deeper aperture and better shutter speed for the conditions and see if I can make this work out. I’m confident in the process, it has just been a slow evolution with widely spaced experiments. Here’s hoping the next (last) blog post will have a truly successful image of trees that engages a viewer in a new way. Aaron The last two weeks have spanned the Christmas and New Year’s holidays, and I took the opportunity afforded by a two-week vacation from work to read a couple of books on photography. First, I plowed through Mary Warner Marien’s Photography: A Cultural History, which Eric had pointed me toward at the beginning of our Bridge Residency. This comprehensive, thoughtful, and richly illustrated textbook not only covers key highlights of the history of photography but also situates its different developments in their cultural settings. As I’ve never taken a survey course in the history of photography, this was a welcome introduction to an artistic and documentary medium that I’ve worked with for more than 50 years. Second, I read Hagi Kenaan’s new book, Photography and its Shadow. In contrast to Marien’s Cultural History, Kenaan’s Photography and its Shadow is a dense philosophical argument about how photography literally instantiates the relationship of people to nature, time, and death. Through a deep dive into the meaning of William Henry Fox Talbot’s 1839 description of his “photogenic drawing” (one of the key first inventions in the history of photography) as the “art of fixing shadows”, Kenaan argues that photography “is a medium that, while appearing within the bounds of culture, allows nature to show itself from within” (Shadow, p. 131). Kenaan goes on to suggest that “the shadow [i.e., the instantiation of the visual in a photograph] is an instance of nature’s ability to represent itself” (Shadow, p. 135) and that “photography’s inner logic has no sense of the contingent values, practices, or forms of meaningful involvement that constitute the human world” (Shadow, p. 154). This approach is somewhat at odds with Marien’s emphasis on “the historical and cultural context in which photographers lived and worked” (Cultural History, p. x). Indeed, Kenaan devotes one chapter (nearly half of Photography and its Shadow) to a discussion of the importance of Oscar Gustav Rejlander’s 1857 photograph The First Negative as an illustration of the distinctiveness of photography relative to drawing (see Joseph Benoit Suvée’s 1791 chalk drawing/painting The Invention of Drawing) and painting (see Jean Raoux’s 1714-1717 oil painting The Origin of Painting); The First Negative (nor the tale of The Maid of Corinth, from which each of the aforementioned works is derived) is not mentioned in Photography: A Cultural History.

For me, Kenaan’s analysis of photography lays out the beginning of a route to the non-anthropocentric aesthetic that I discussed in my previous blog post. Kenaan writes that photography has the “ability to conjure views that are indifferent to man’s being-in-the-world” and its “space consists of an indefinite multitude, a plurality of viewpoints that refuse to coalesce” (Shadow, p. 157). In this, he echoes Emerson, who’s fundamentally uncaring nature is “something mocking, something that leads us on and on, but arrives nowhere, keeps no faith with us” (Nature, in Essays II [1844] p. 396 in 1981 edition). In the same way, photography for Kenaan “moved to erase the specific conditions that were traditionally associated with the artist’s ability to create images out of natures imagistic potential (Shadow, p. 33), creating in photography not only Kenaan’s “separation from the natural world (Shadow, p. 37), but also a separation of its aesthetic from the requirement that beauty requires an (human) observer. Eric I’m back with more linear panoramas! The 200mm lens is still working quite well for me, it allows for a foreground and background relationship that feels just about right in relation to all the image/world relationships discussed in previous posts. I am even starting to feel good enough about these images that Aaron and I are entering some of them with our work to calls for proposals. The image I have identified with the most forward potential here is figure one; it has a compositional spacing that works in a unique way that I think I can build upon. Specifically, there is a front-to-back and side-to-side rhythm which is complementary, and that is not reduced in any way by a “too full” frame. In fact, there are many vines and thorns that were swept away by Photoshop during the focus stacking and panorama-melding processes that would be welcome here. To bring those parts of the world into the image, I plan to return to the site with a more deterministic photographic set up. I will take two tripods, and span a board between them, moving the camera left to right by a set distance. This will give me far more accuracy than I currently have, trying to move a tripod over uneven ground, and framing the next image by memory of the preceding one. I should also be able to achieve better focus stacking with this new process as well, because I will be able to concentrate more on the focus steps than all the other factors going into the shot. The major downside to this is the added equipment, complexity, and planning that will go into each image. It is much easier to walk through the world with a camera on a tripod and happen upon a place than to cart around a large set up that takes a good amount of time, and will no doubt attract attention from any passers-by. The trick to the work will be to get the technical aspects polished while keeping as much of the spontaneous compositions that happen from an easy walk through the woods in the images. The other necessary next step is to take one of these images to a print-level state, and to make test prints. The files are very large, and can accommodate printing at almost any scale. It is tempting to use the largest paper I have and see what happens, but I think I will stick to a testing mode and make smaller (24” high by whatever length) prints at first. With any luck, these next few steps will come together in the next few weeks. Aaron Today is the winter solstice - the shortest day of the year here in the northern hemisphere – and there is palpable pleasure in knowing the daylight hours will now be steadily lengthening. The solstice this year was also marked by the “great conjunction” of Jupiter and Saturn, when, to viewers on Earth, they appeared closer together in the sky than they have in nearly 800 years. Not surprisingly, the co-incidence of the solstice and the conjunction have spawned all sorts of eschatological prophecies and pronouncements, which can be revealed by even a cursory Internet search and make for disturbingly fascinating reading. In this dim light, Eric and I have been discussing how we might combine ecological thinking and photography-as-art to promote an aesthetic that is ecologically informed yet not anthropocentric (with an eye towards contributing a paper/exhibition to next year’s annual summer conference of the International Institute of Applied Aesthetics). We are grappling with two significant challenges in defining a non-anthropocentric aesthetic of environmental stasis and change. First, aesthetics is the philosophy of the beautiful or of art; a system for its appreciation; or the distinctive underlying principles of works of art, artists, culture, etc. Because aesthetics requires perception, appreciation, and high-minded critique of art and beauty, it is decidedly human-centered (anthropocentric), so the proposition of a non-anthropocentric aesthetic is prima facie, a non sequitur. Second, ecology has evolved into a decidedly anthropocentric discipline. Our departure from the Holocene and subsequent arrival into the Anthropocene has been marked by the replacement of biomes by anthromes, declarations by various organizations and governments of a “climate emergency”, and pronouncements that humans are destroying the planet lends strong credence to Montaigne’s assertion (ca. 1580) that [a]insi fera la morte de toutes choses notre mort (our death will bring about the death of all things), which Morselli unpacked in his novella Dissipatio H.G. (1977) (which presaged by decades the more familiar The World Without Us and Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils): One of the pranks played by anthropocentrism is to suggest that the end of our species will bring about the death of animal and vegetable nature, the end of earth itself. The fall of heavens. There is no eschatology that doesn’t assume man’s permanence is necessary to the permanence of anything else. It’s accepted that things might have been before us; unthinkable that they could ever end after us. Ecologists can describe - and document with photographs - what is and what has been and apply various models to forecast what might be. We may even be able to test the forecasts with emerging and photo-documented data - but this begs the question of what will be without us around to observe, measure, and record it. Photography can record what is and what was, but how might we photograph what could be? This question is also at the heart of a debate that has been ongoing since the invention of photography: whether photography is only objective (i.e., scientific), soulless and constricting of human imagination, whereas artists see with their souls and create what they dream. But consider: Eric Picking up from the lessons learned two weeks ago, I set out to create a linear panorama with a 200mm telephoto lens, to see if this focal length would produce the outcomes Aaron and I have been talking about - a view of the forest that reveals the individual trees and plants, as well as the connections between the organisms. I started by testing the lens on the same view - and traditional-style panorama - I made with the 500mm lens two weeks ago, but this time I stood closer to the edge of the trees, and photographed a smaller section. You can see that the results are quite different in Figure 1 from those of the longer lens. The 200mm lens is much sharper and reproduces color far better, which is honestly a little astounding given that it is really just a cheap lens that comes standard in a Nikon camera kit. This increase in sharpness and color contrast is likely due to the superior coatings on the optics and the increased tolerances for lens manufacturing from recent times. Being closer to the edge of the trees also creates a better entry to the identification of and interest in any particular specimen. This was an exciting development, and I knew at this point that results from a linear panorama should be better than previous tests as well. I made 11 photographs in a straight line on what is the right edge of the forest pictured above. When first importing them into Photoshop, I thought I might have some material that the program would know how to stitch together, but this was not the case. Figure 2 shows the failure of Photoshop to connect most of the edges. This issue cropped up with Aaron’s panorama’s (found in his post from this week) as well. I decided to manually stitch the images together and happily it was very easy to do, and produced the best result from all of these tests yet (Figure 3). I am quite happy with these results, as the forest has depth as well as a real (and strange) width that changes the viewer’s relationship with the information just enough (I hope) to generate a deeper look. I now plan to try out this method on more subjects to see if the results are reproducible. Aaron The two weeks since my last blog post have overlapped with a writing workshop facilitated by Charlotte Du Cann and Nick Hunt (editors with the Dark Mountain Project) that I had the good fortune to participate in. Our main assignment was to think of a wild place/space to walk (in)to, walk into that space at dusk, and look for stories there that needed telling. Nick suggested a few different exercises to do to (un)focus our attention, including “horizon-lining”, in which one focuses their eye on a point on the horizon and then very, very slowly turning a full circle and following that horizon point around the circle. As Eric and I have been working on how to photograph and post-process panoramas to reveal new kinds of information, I thought that horizon-lining could provide an interesting way to visualize the competing ecologies of a particular wild space: the often-overlooked wetlands that exist in the margins and on the edges between rivers and roads (Figure 1). I took two sets of photographs. The first set of 21 images were taken at a 28-mm focal length (wide-angle). Panoramas constructed using standard post-processing (with Adobe Photoshop; Figures 2 & 3) were workable but surprisingly (at least to me) did not reflect the order in which the photographs were taken (Figure 4 shows the panorama in the “correct” order). As the photographs encompassed a complete circle, though, “order” is an aesthetic choice; perhaps it would be better to display these as a circle with the viewer able to view them in any order or from any angle).  Figure 2. Wetland by the Watertown (Massachusetts) Storm Drain Outfall, Dec. 1, 2020. Panorama constructed from 21 images (28-mm focal-length) by Aaron Ellison; post-processing (correcting for lens distortion, vignetting, and chromatic aberration) and panorama stitching by Eric Zeigler using Adobe Photoshop. With the intention of focusing on the wild space, the second set of images “zoomed in” on the wetland. Using a long focal length (300-mm) and low f-stop to deliberately render the urban background out-of-focus, I needed 86 images to complete the circle. Although I have been able to stitch sections of the image together using Canon’s PhotoStitch (software that is nearly 20 years old and no longer supported) (Figures 5 & 6 show panoramas of the first 10 and last 14 of the images), Photoshop was unable to automatically piece the panorama together. There appear to be too few landmarks and too much motion (from the strong wind blowing the tops of the reeds) for accurate computation. What insights does this provide about how technology and specific visualizations force particular alignments or interpretations of landscapes and their ecologies? Eric This week I continued technical photographic experiments with panoramas. So far the biggest technical problem with making a linear panorama has been the occurrence of parallax error, which in this case, ends up as the copying of background information across multiple images. This has confused the software I’ve used to make these panoramas, and in order to continue working this way with any hope of automation, I needed to figure out how to create an image with less background oversampling. One way to reduce the parallax is to use a longer, or more telephoto, lens. Using a longer lens reduces the angle of view, and creates less of a parallax shift from one image to another, because we are looking at a thinner angle of the world. I grabbed an old 500mm Minolta-mount mirror lens from the photography department, and using an adapter, I attached it to a Nikon D800e digital camera (figure 1). I started with a simple single-point panorama to assess the lens and camera set up. I found that the lens is not perfect, and due to its low potential for sharpness and the slight breeze that was vibrating the camera and tripod, the results are not sharp even though I used an electronic cable release. Nonetheless, they were usable. The images were taken from a distance of around 700 feet from the edge of the woods (figure 2), and as a result, look—and more importantly—feel very distant from the viewer. I knew this was one possible outcome, as telephoto images look “flatter” than our normal vision, but what I did not anticipate fully was that the distance also keeps the viewer from entering the forest in the image. As you can see in figure 3, the total effect of the combined images does not necessarily create an image of the forest that provides for a view of the whole and its parts, but rather an image of the whole of the edge of the forest emerges. This flatness is undesirable for the effects that Aaron and I have been conversing about, so for next time, I plan to use a 200mm lens, which will allow me to get closer, and perhaps end up with a more “Goldilocks” version of an image that shows the trees and the forest equally. Aaron The days are noticeably shorter now here in Massachusetts; sunrise today was at 06:45 and sunset at 16:15, so it’s still dark at breakfast and it’s long been dark before the end of the workday. Most of the trees are bare of leaves, even in parking lots warmed by heat-absorbing asphalt and the generally warmer cities by the coast. It is a good time to contemplate ecological transformations. Someone lacking in ecological consciousness who walks through a forest at this time of year might feel surrounded by death and dying. Dead leaves crackle underfoot, flies and mosquitoes gave it up with the first frost a few weeks ago, and birds have migrated to warmer climes. Even the trees, which we know will flush new leaves five or six months from now, are mostly “dead”: most of a standing tree consists of non-functioning cells (“heartwood”) that support its thin skin living cells (“sapwood”). But the forest is neither dead nor dying. Metabolism continues in the sapwood. Bacteria and fungi are hard at work decomposing the leaves and the carcasses of dead animals into their component minerals and eventually transforming them into the nutrient-rich soil that nourishes the herbs, shrubs, and trees when they awaken or sprout next spring. These transformations are happening all the time - if they weren’t, we’d quickly find ourselves up to our armpits in the disintegrating corpses of the plants, animals, and even other humans who have lived out their lives. Ecologists like me study the dynamic, evolutionary processes, including birth, reproduction, death, decomposition, reuse, and transformation, that lead to the continual rebirth and recreation of the material world. The creative arts capture a single instance in—or in the case of video (for example), a short interval of—in time and space. I return to a fundamental question that Eric and I continue to discuss: how do we use an essentially static medium to make change visible and to reveal what may appear to be gone but is, in fact, transformed and remade?

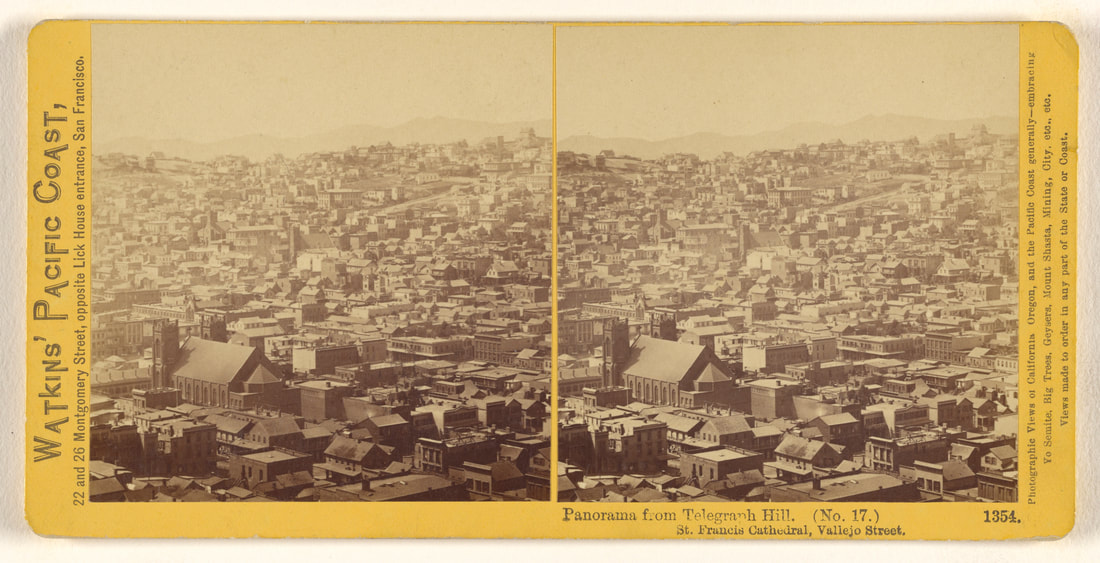

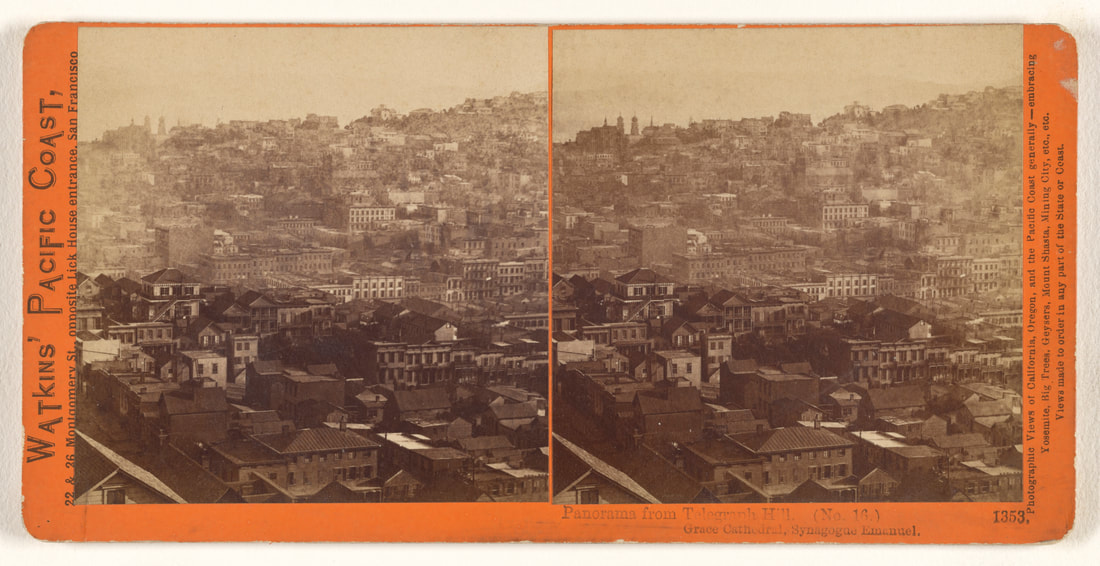

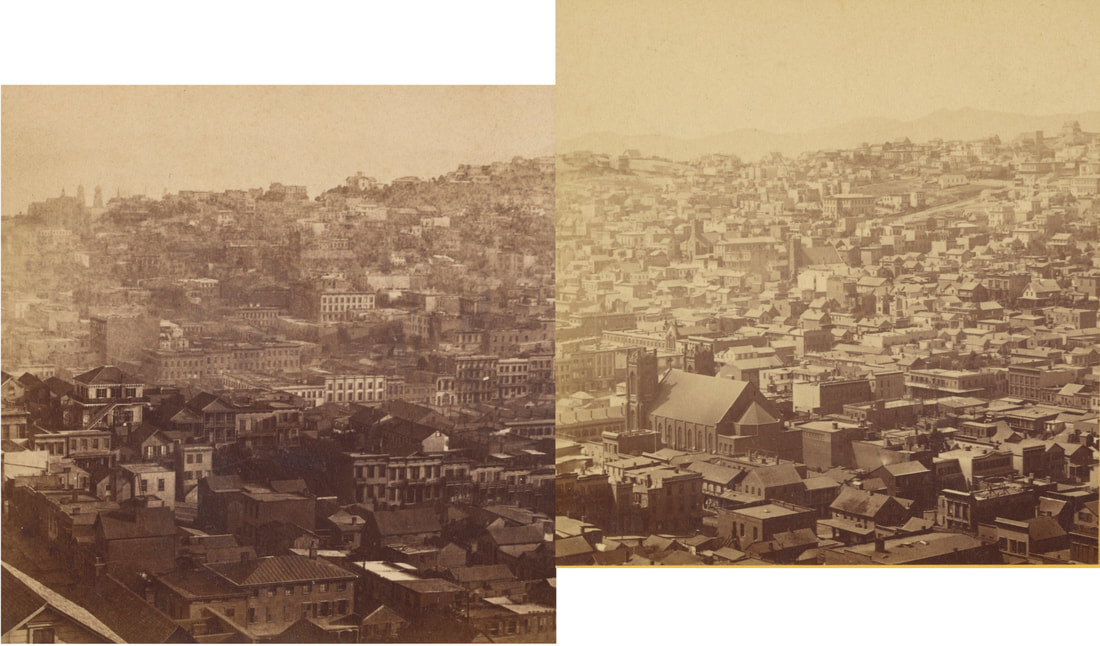

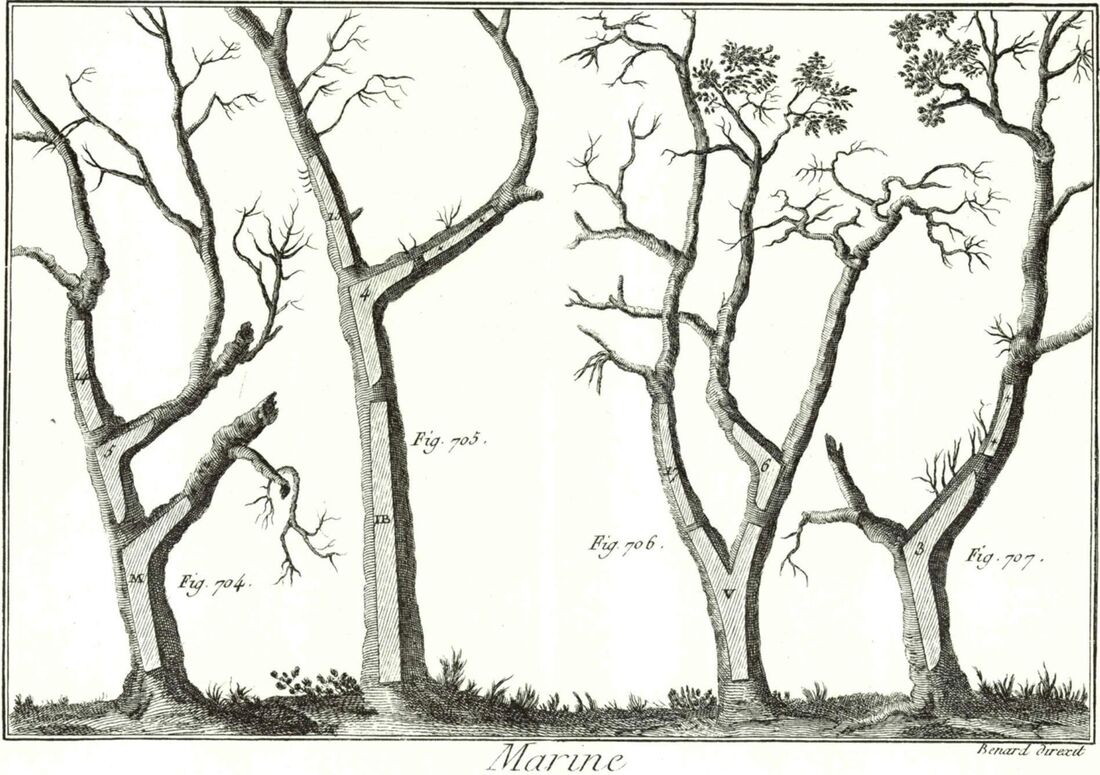

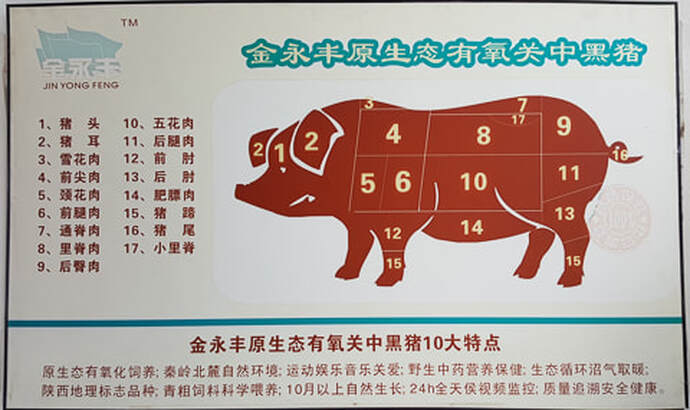

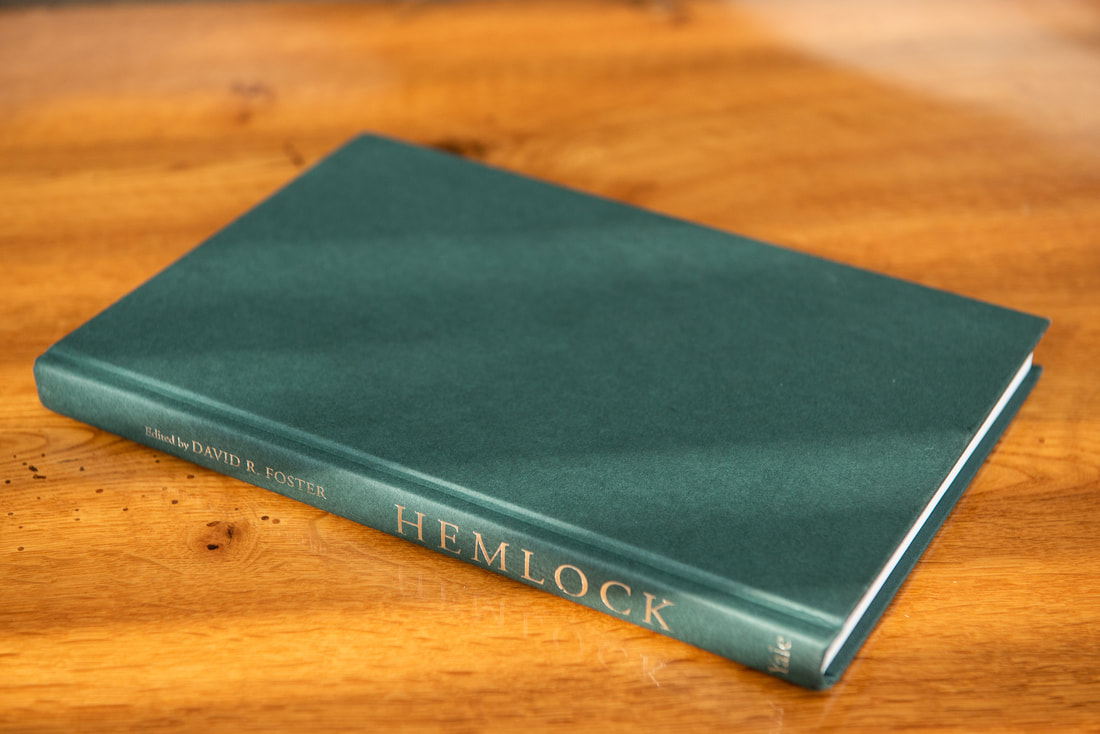

Eric These past two weeks have been spent applying to a Duo residency at ArtExplora with Aaron and continuing to make new attempts at panoramas. The search for a new panorama methodology is a component of the residency application, but also an attempt at making images of forests that confront a viewer with visual information in a way they have not experienced before. Before I get to the new tests, I want to point out a few panoramas from photography’s past that I have been thinking about this last week as well. The first is Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip, from 1966, which Ruscha has actually been rephotographing every couple of years. Ruscha is interested in changes taking place along the strip, and tells the NY Times that he wants to have the changes “nailed down and captured.” I find the sentiment to track, or acknowledge, change compelling, and I also like the way that Rushca did not hide the camera’s lensing with the construction of the panorama. Technically, it’s worth noting that Ruscha’s images work as a linear panorama because they are scanning a single plane - the building facades - and as you look deeper into the perspective in the images, the connections start to break down. Another image that works as a panorama, but is constructed quite differently is Art Sinsabaugh’s Railroad Crossing #24 - ⅔, 1961. This image tracks the flat midwestern landscape using a large format camera and a long (telephoto) lens and then becomes a linear panorama by cropping off the top and bottom of the image. This creates an absurd flatness, and an ability to compare the relative size of objects that are quite distant from one another that begins to reveal a connectedness that I would like to have in my own panoramas. This connectivity is also emphasized by the lack of any separate frames being artificially tied together. The last panorama I’ve been looking at is a stereoview panorama from the top of Telegraph Hill in San Francisco in about 1867 by Carleton Watkins, see in part here in Figure 1 and 2. The images are unique in that they are made to be a round panorama of the city, but are meant to be seen separately (only 16 and 17 seen here), and in 3D Stereoview. For me, there is an intriguing compromise made here between the spatial experience of a place, and the time needed to switch to another stereoview, and the imagination required to place oneself in the next image, relative to the last. I’ve provided a crude combination of the above images below (Figure 3) to make it easier to see how they line up. While there is still quite a bit of work to do to combine the technical functions of these historic images into my panoramas of forests, I have made some new images that start to stretch the tools I have at hand. (Figures 4-7). I have learned that the longer my lens, the better a linear panorama I can achieve, and I have also tried to stretch the limits of Photoshop’s canvas size by manually combining multiple iPhone panoramas together, which represents an entire stretch of recently colonized farmland. The lens makes for a more legible panorama but also introduces strange variances in the color consistency of the combined image. These tests are continuing to get closer to the newly-imaged forest Aaron and I have been talking about, and I am excited for the next experiments. Aaron I continue to consider the scientiartistic coproduction of reality and its subsequent perception by practitioners and viewers. This entry is inspired and informed by the overlap between Eric’s and my shared interest in and practice of photography and woodworking We have been considering how we can simultaneously see and know individual trees while visualizing and understanding entire forests. At the same time we have been exploring this question through different kinds and manipulations of panoramic photographs, we also have been thinking about transformations of trees and forests into material (“wood”) from which we create and envision abstractions of trees and forests in aesthetic and utilitarian objects. In our research, we came across a fascinating illustration from the Encyclopédie Méthodique de la Marine (ca. 1783). Here, oak trees are envisaged as a series of cuts - analogous to cuts of meat - each of which would have a particular use in the building of a boat. The creation of a boat (or a fine meal) not only takes materials but also takes years of practice. The end result needs to float, but the addition of artistic design and fine craftsmanship can transform a utilitarian object into something entirely different. In this transformation, we gain an objet d’art but we often lose the intimate connections with our understanding and appreciation for its source materials. From a tree to a boat. Top left: Western red cedar (Thuja plicata), H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, Blue River, Oregon; Bottom: Kayak baijitun (白暨豚), constructed of three different kinds of cedar (Western red cedar, Alaskan yellow cedar, Eastern white cedar) and black walnut; Top right and center: details of bow, cockpit, and stern of the baijitun. Red cedar designed by evolution; kayak design (North Star) © Rob Macks/Laughing Loon; kayak construction by Aaron M. Ellison; and all photographs © Aaron M. Ellison. Can these connections be recreated only with photodocumentation, and what is the additional role of Benjamin’s “tiny sparks of chance” in triggering awareness and implied transformations?

Eric The last two weeks have been spent continuing the attempts to find the limits, or flaws, of the imaging software I’ve been using, and to understand better the act of looking at a forest, or an ecosystem. First, I’ll bring us up to date on the images. I made photographs in two different locations this time, the first at the Fallen Timbers Battlefield Park, and the second at “The Spot” in Oak Openings Metropark. The Battlefield location was chosen out of convenience and interest; the maples were exceptionally bright in color that weekend, and “The Spot” is an example of a plantation forest, which Aaron and I had been chatting about in our weekly meetings. At the Battlefield, I attempted to be more systematic and precise while taking the initial images which were later fed to Photoshop. For the first image, I laid down a string to demarcate a linear viewing area, and then I moved the camera and tripod 9” to the right after each exposure. For the second test, I used a bridge in the park as a guide for the tripod legs, and moved to the right 8” at a time, including the bridge railing in the base of the images so Photoshop might have something linear to grab hold of while calculating a panorama. As you can see, neither test went according to plan. The first image (fig. 1) collapsed over itself, as the cacophony of leaves and branches melted into one another and became distorted. In the second (fig. 2), the bridge railing helped, but only served to make the image edges choppy instead of smooth for some reason. Of course, I expected the results to be unrealistic, given that the program was being fed information outside its intended inputs, but usually, that is the process I use to find out exactly what the limits for inputs to a program are. Strangely, when using an iPhone to create a panorama (an iPhone 6s in this case), I was able to walk in a straight line and gather an image that made some sense, as seen in the image from “The Spot” below (fig. 3). As I mentioned above, I went to “The Spot” because it is a remnant of a plantation forest, planted by the WPA in order to hold the sandy soil in place in the area and to provide a revenue stream for the parks. Aaron and I are interested in the plantation forests as examples of constructed environments, and we are curious about what the process of studying and imaging them may bring about. Due to its age, this particular forest has a short life span ahead of it, despite being a hugely popular local site for posed photographs. (Just search Instagram for “Oak Openings” and you will see what I mean.) It’s also worth noting that this tiny spot (fig 4.) more than likely has served more often as a backdrop for images, and is more widely known than the entire painstakingly restored and preserved park around it. To see what a “normal” panorama of the same view looks like, you can compare the image to fig. 4. Aaron A common question for scientists involved in art/science collaborations is whether art changes (or at least influences) science. This topic was explored in some depth two years ago in SciArt Magazine (October 2018). My own contribution, co-authored with my long-time collaborator David Buckley Borden, concluded that “major breakthroughs or innovations from art-science collaborations are more likely to be the exception than the rule”, but that as scientists working in collaboration with artists that we can expect to have our assumptions challenge, our work refracted through new creative lenses, and gain new sets of critical thinking skills that expand our scientific practice in unexpected ways. The value of the unexpected was brought home to me last week when I read Ruth Margalit’s review of several novels by Ronit Matalon that have recently been translated into English from their original Hebrew. Most chapters of Matalon’s novel The One Facing Us open with an old photograph of the narrator’s relatives. Margalit notes that the chapters then focus on minor, easily overlooked, or unintended details of the photographs. She then draws in Walter Benjamin’s observation in his 1931 essay “A Short History of Photography” that the viewer of a photograph (Benjamin’s “spectator”) : “feels an irresistible compulsion to look for the tiny spark of chance, of the here and now, with which reality has, as it were, seared the character in the picture; to find that imperceptible point at which, in the immediacy of that long-past moment, the future so persuasively inserts itself that, looking back, we may rediscover it.” (from the 1972 translation by Stanley Mitchell) The ”tiny sparks of chance” in photographs are analogous to the detailed, often serendipitous observations that send scientists and their research in unanticipated directions. The remarkable, often unexpected natural-history observations made from the late 18th through the 19th centuries were grist for theoretical mills that annealed ecology and evolutionary biology into a new science. Among many examples, Darwin and Wallace’s years of meticulous observations and experiments inspired and grounded the theory of evolution by natural selection, while von Humboldt’s explorations set the basis for our understanding of how distributions of plants and animals are governed by climate – theories that still guide our models and forecasts of the effects of ongoing global climatic change. Yet, the institutionalization of ecology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was paralleled by a devaluing of natural history, which was left to “amateurs”, while professional ecologists focused on developing general theories often unconstrained by data. And just as ecologists could ask whether natural history was still science (a question still posed today), Benjamin highlighted tensions between art and photography: photography as art, art as photography, and photography of works of art. “A Short History of Photography” was written 90 years after the invention of the daguerreotype. Now, 90 years further on, Benjamin’s “tiny spark of chance” continues to sear photographs, but his subsequent lines highlight new intersections between art and science: “It is indeed a different nature that speaks to the camera from the one which addresses the eye; different above all in the sense that instead of a space worked through by a human consciousness there appears one which is affected unconsciously.” (from the 1972 translation by Stanley Mitchell) Just as photography and other creative arts are increasingly shaped and impacted by emerging technologies (discussed recently by Hans Ulrich Obrist), so ecology and our understanding and interpretation of nature increasingly is determined by webs of sensors, computers, data clouds and models that interpose themselves between our eyes and our brains. Interrogating Obrist, I pose the question: what is implied about us and our world in this scientiartistic co-production of reality?

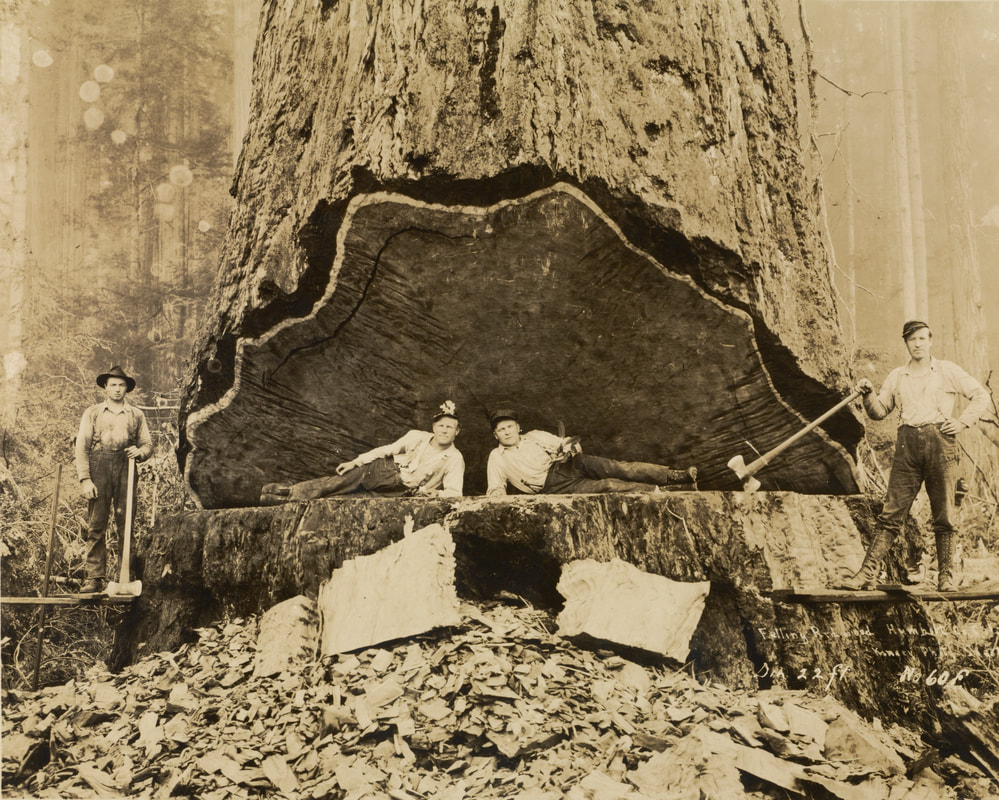

Eric As a first step towards considering what we can do through our collaboration, Aaron and I have been discussing in greater detail our areas of knowledge and research, our interests, and the questions we still have about that research. I tend to first be interested in the historical contexts for whatever subject I’m researching, so I put together and shared with Aaron a slideshow of images to articulate what I think of when I think of images of trees and the natural world in various contexts. The photographs started with images similar to this one below by Darius Kinsey titled Falling Redwood, Humboldt County, California, 1906, and ending with contemporary images by Trevor Paglen and Taryn Simon. In turn, Aaron sent me a copy of Hemlock: A Forest Giant on the Edge which answered many of my questions about the Harvard Forest, which we are planning to photograph in some way. Through this exchange of information, we have been able to narrow down our set of questions about trees and photography. One large question among many we are considering is: How do you photograph a forest? There are numerous histories of documentation, archives, and scientific endeavors to understand forests, including Harvard Forest’s own archive of images. One aim of documentation has been to understand a system in its entirety. The issue that immediately crops up when trying to understand a dynamic system like a forest through still photographic images is the inherent contradiction between the multiple time-based interactions in the forest and the singular point of view of a photograph. Other artists working in the past, and even currently, have created ways around this problem by looking only at specific components of a tree, or to make a narrative series of images that attempts to convey a story that is adjacent to the documentation of the forest itself. Another way to frame the question How do you photograph a forest? is: What does a forest look like? This is helpful because it takes the problem of the tool (the camera) out of the process for a moment. When I stand in a forest, and in this case, it is a forest near my home, Goll Woods, I am not just focused on individual trees, but also on the distances between large and small trees, the canopy height and density, the animals on the forest floor and birds in the trees, and the motion of these objects through time. After noticing that being in the woods for me is about seeing the system, I can now bring back the camera. In a first attempt at essentially sketching out a way to use a camera in the woods, I made the photograph below, which is a composite image in multiple ways. First, it uses a technique called focus-stacking to layer multiple images from the same point of view on top of each other to create an image with maximum focus from the lens to the background. Second, I combined those focus-stacked images into a panorama to give a perspective of the forest, based not on single-point optics, but more on what it looks like to walk through the woods. This experiment is sure to be just the first sketch of many in an attempt to resolve some of these fascinating questions that Aaron and I have started to consider together, I hope that the images will become further complicated as we investigate more the way that humans interact with and look at the world’s forests. Aaron These last two weeks our conversations have included discussions of intention and communication in art, science, and sci-art. As a practicing scientist and collaborator with artists and designers, and artful creator, I continue to struggle to identify and define the various roles that sci-art (and more specifically in much of my own work, ecological art [eco-art]) can take on. Some additional ideas percolated up last week when I watched the “Beijing” episode of the 10th season of Art21’s Art in the Twenty-First Century documentary video series. The segment featuring Xu Bing was especially clear in identifying the deliberate intentionality in his work. Notable examples for me include his Background Story series (ongoing since 2004), which I saw when it was at MassMoCA in 2012 and wrote about in an article I published a couple of years later, and his Square Word Calligraphy series (ongoing since 1994). Xu Bing’s work, like that of the photographer Richard Misrach (featured in the “Borderlands” episode of Art in the Twenty-First Century), stood out for the intentionality of their creators. In contrast to most eco-art that I have viewed or created, Xu, Misrach, and Guan Xiao (also featured in the “Beijing” episode) appeared to me to be much less interested in communicating a specific message than in provocatively providing a space for viewers and audiences to rethink their own underlying assumptions and reimagine new possibilities for different worlds.

Eric I’m an artist, designer, researcher, woodworker, gardener, and professor. I received my BFA in photography from Bowling Green State University and my MFA from San Francisco Art Institute. I teach photography, digital media, art history, drawing, tools, and Biodesign at the University of Toledo. My recent personal work is photographic, and is made with an array of imaging technology: high-resolution digital cameras in studios, drones, Micro CT scanners, and computer display capture to create the final images. Each piece is conceived individually, based on research into the scientific, cultural, and photographic importance of each object or place. The resulting prints range from overwhelmingly large to quite small in scale, intuitively referencing historical photographic conventions (landscape, the sublime, and historical scientific imagery). I also make all the frames for the photographs, because, in addition to controlling the quality of presentation, the usage of the frame reinforces the image’s presence, history, and separation from the lived world. Each piece is framed according to its shape - for instance, the round images are displayed in circular frames. When conceiving my work, I consider questions such as - How does an image arise in the world? What are the necessary conditions and materials needed to make discoveries through images and exploration? To put it another way, I’m interested in creating images that engage the viewer in the conceit and deceit of the image’s actual construction, while utilizing well-known methods of seductive image creation. As a whole, the work questions the efficacy of being in a place to factually photograph and understand it, and what the exploration of a place, or outer space, means to the contemporary world of photography. Our seen version of the world has been simultaneously explored and photographed while we walk through it, and the photographs I make reach into the previously unseen. In addition to questioning the action of making factual photographic images, the images scrutinize the materials necessary to perform this work. What materials are extracted from the Earth to create these photographs, and what are the costs to us and the planet? Is the image that results worth the material extraction involved if the facts as presented by the photograph are suspect? As images are increasingly taken as “pure” fact in our culture, I aim to understand and continue to inspect these mechanisms which create persistent cultural narratives. As a woodworker and image-maker, I am lately increasingly interested in the complexities of the materials of the wooden frames that I make for my photographs. Looking beyond just a named location of the source lumber, what are the criteria that go into harvesting the trees, and has information about the fitness of a tree for its final use been lost through mechanized harvesting? Also, what relationship does the use of a tree for an image have to the health of the forest? Attempting to understand the photographic process as a biological and mechanical process is something I am excited to start to explore in this residency. Aaron It’s very exciting to be part of the 2020 Bridge Residency cohort! I see it as a great opportunity to work with Eric (and perhaps others in this cohort) to explore new ideas, pick up on some simmering ideas in new contexts, and walk a different path from my “normal” work as a scientist and academic administrator. Scientists and artists alike are explorers of the unknown worlds beyond our current understanding. We may use different approaches and languages to communicate our discoveries, but we share the common goal of illuminating what has not been seen before. In our case, Eric and I have already met three times (via Zoom, of course), and have found common ground in photography and woodworking, complexity and dynamic systems, forests and oceans, and in how to deal with the cognitive dissonance and disconnection between a static photographic image (or more generally, an artefact) and the complex dynamics that characterize the world we live in. What do I bring to this collaboration? I am an academic ecologist and statistician by profession but find additional creative expression in cooking, photography, sculpture, creative and non-technical writing, and woodworking (examples of all but the cooking are here). For almost 40 years, I have done research on how ecosystems are organized and structured; how plants, animals (including humans), fungi, and microbes interact with one another and their external “environment”; what happens to ecosystems disintegrate when they are “disturbed” by often unexpected “natural” or anthropogenic events; and how they reorganize and restructure themselves following these disturbances. I am particularly interested in how systems behave as they pass through “tipping points”. I have studied these processes and dynamics with simulation models and in the field in person and with many colleagues on every continent. My favorite places to be in are forests - especially the old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest, swamps, marshes, and bogs, and my favorite organisms are (in alphabetical order) ants, eastern hemlock trees, mangroves, melastomes, and carnivorous pitcher plants. A sixteen-week residency will pass very quickly—we’re already two weeks into it—and we’re already thinking about tangible projects. These include [1] photodocumenting the dynamics of a managed forest stand at the Harvard Forest in the context of stasis and dynamics, growth, logging, (re)use and (re)generation while attempting to capture the rapidly disappearing intuitive human feel for the trees themselves and [2] a proposal for a session or installation at the 2021 Borrowed Time summit.

Meanwhile, I find time to kayak and bike while working through my obsession with snags. |