|

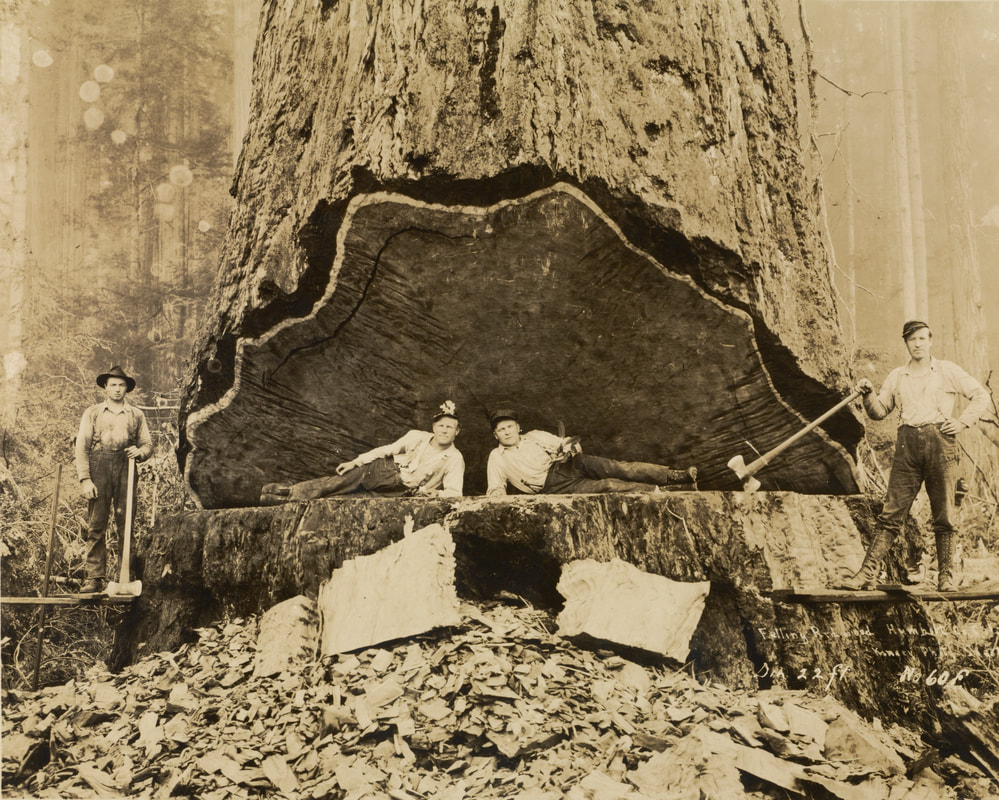

Eric As a first step towards considering what we can do through our collaboration, Aaron and I have been discussing in greater detail our areas of knowledge and research, our interests, and the questions we still have about that research. I tend to first be interested in the historical contexts for whatever subject I’m researching, so I put together and shared with Aaron a slideshow of images to articulate what I think of when I think of images of trees and the natural world in various contexts. The photographs started with images similar to this one below by Darius Kinsey titled Falling Redwood, Humboldt County, California, 1906, and ending with contemporary images by Trevor Paglen and Taryn Simon. In turn, Aaron sent me a copy of Hemlock: A Forest Giant on the Edge which answered many of my questions about the Harvard Forest, which we are planning to photograph in some way. Through this exchange of information, we have been able to narrow down our set of questions about trees and photography. One large question among many we are considering is: How do you photograph a forest? There are numerous histories of documentation, archives, and scientific endeavors to understand forests, including Harvard Forest’s own archive of images. One aim of documentation has been to understand a system in its entirety. The issue that immediately crops up when trying to understand a dynamic system like a forest through still photographic images is the inherent contradiction between the multiple time-based interactions in the forest and the singular point of view of a photograph. Other artists working in the past, and even currently, have created ways around this problem by looking only at specific components of a tree, or to make a narrative series of images that attempts to convey a story that is adjacent to the documentation of the forest itself. Another way to frame the question How do you photograph a forest? is: What does a forest look like? This is helpful because it takes the problem of the tool (the camera) out of the process for a moment. When I stand in a forest, and in this case, it is a forest near my home, Goll Woods, I am not just focused on individual trees, but also on the distances between large and small trees, the canopy height and density, the animals on the forest floor and birds in the trees, and the motion of these objects through time. After noticing that being in the woods for me is about seeing the system, I can now bring back the camera. In a first attempt at essentially sketching out a way to use a camera in the woods, I made the photograph below, which is a composite image in multiple ways. First, it uses a technique called focus-stacking to layer multiple images from the same point of view on top of each other to create an image with maximum focus from the lens to the background. Second, I combined those focus-stacked images into a panorama to give a perspective of the forest, based not on single-point optics, but more on what it looks like to walk through the woods. This experiment is sure to be just the first sketch of many in an attempt to resolve some of these fascinating questions that Aaron and I have started to consider together, I hope that the images will become further complicated as we investigate more the way that humans interact with and look at the world’s forests. Aaron These last two weeks our conversations have included discussions of intention and communication in art, science, and sci-art. As a practicing scientist and collaborator with artists and designers, and artful creator, I continue to struggle to identify and define the various roles that sci-art (and more specifically in much of my own work, ecological art [eco-art]) can take on. Some additional ideas percolated up last week when I watched the “Beijing” episode of the 10th season of Art21’s Art in the Twenty-First Century documentary video series. The segment featuring Xu Bing was especially clear in identifying the deliberate intentionality in his work. Notable examples for me include his Background Story series (ongoing since 2004), which I saw when it was at MassMoCA in 2012 and wrote about in an article I published a couple of years later, and his Square Word Calligraphy series (ongoing since 1994). Xu Bing’s work, like that of the photographer Richard Misrach (featured in the “Borderlands” episode of Art in the Twenty-First Century), stood out for the intentionality of their creators. In contrast to most eco-art that I have viewed or created, Xu, Misrach, and Guan Xiao (also featured in the “Beijing” episode) appeared to me to be much less interested in communicating a specific message than in provocatively providing a space for viewers and audiences to rethink their own underlying assumptions and reimagine new possibilities for different worlds.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |