|

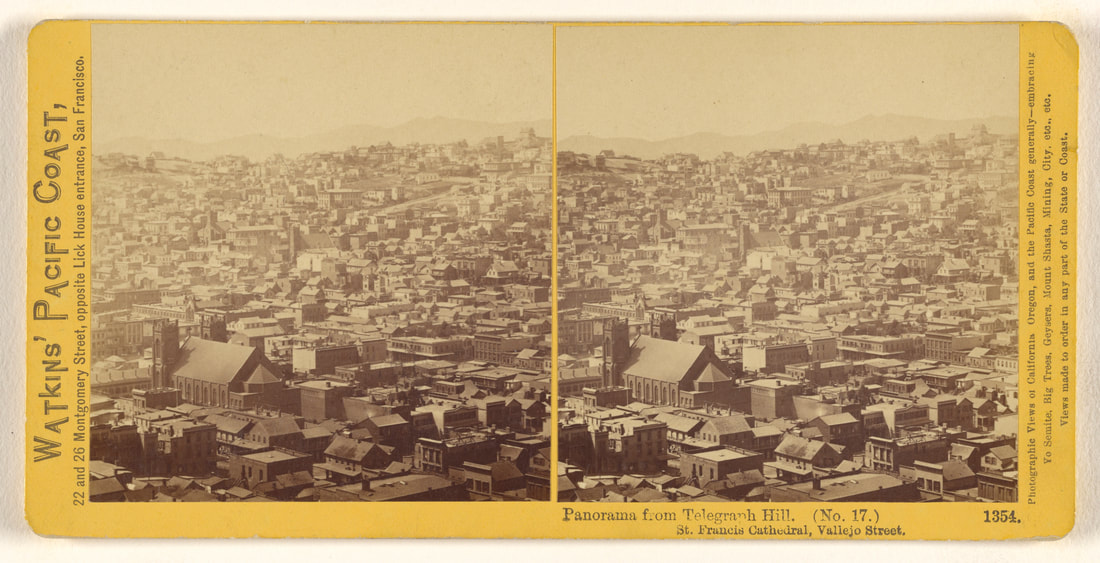

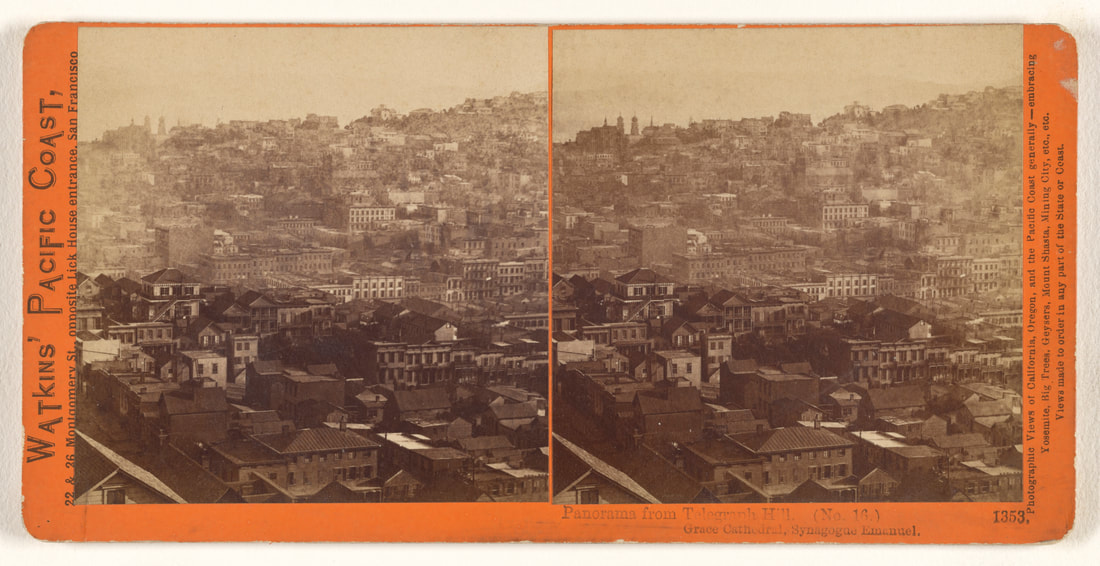

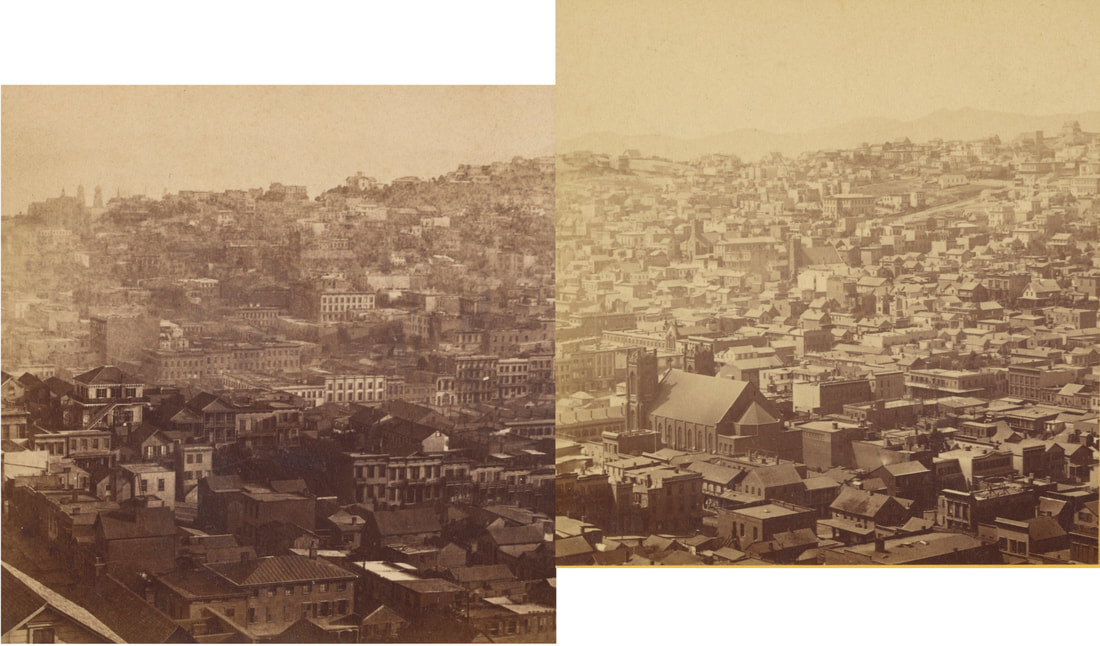

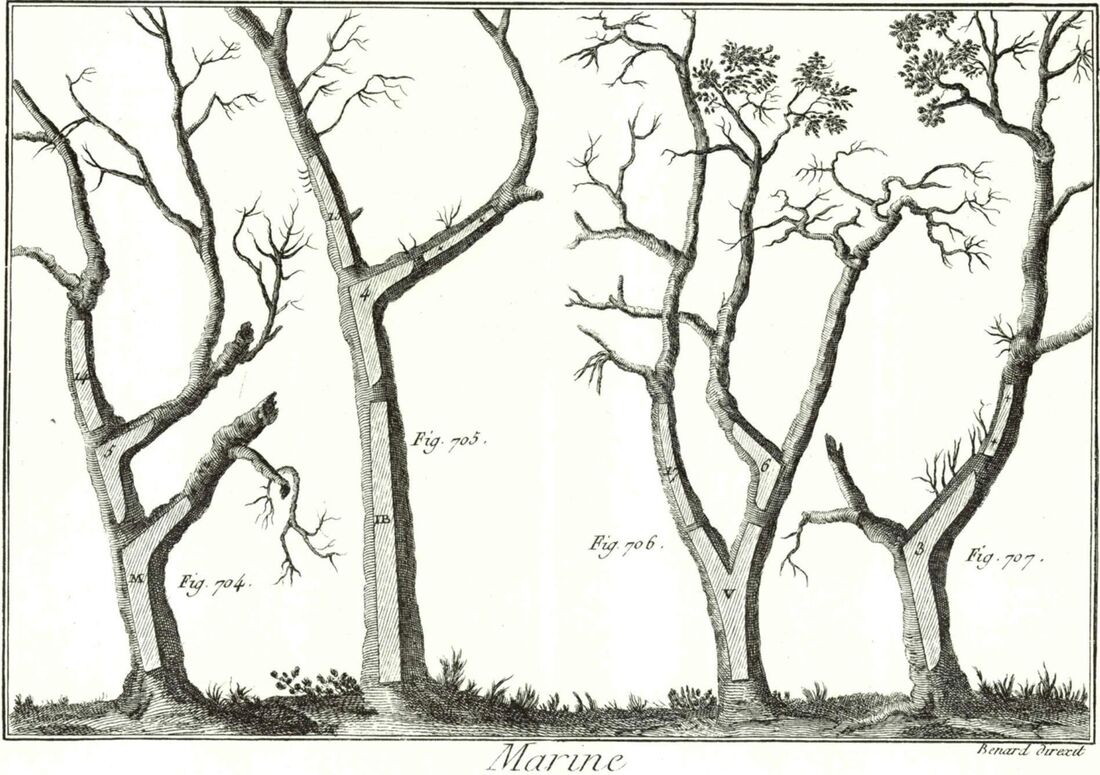

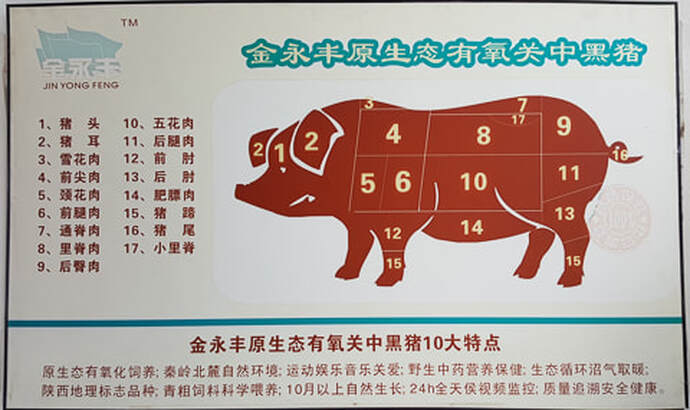

Eric These past two weeks have been spent applying to a Duo residency at ArtExplora with Aaron and continuing to make new attempts at panoramas. The search for a new panorama methodology is a component of the residency application, but also an attempt at making images of forests that confront a viewer with visual information in a way they have not experienced before. Before I get to the new tests, I want to point out a few panoramas from photography’s past that I have been thinking about this last week as well. The first is Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip, from 1966, which Ruscha has actually been rephotographing every couple of years. Ruscha is interested in changes taking place along the strip, and tells the NY Times that he wants to have the changes “nailed down and captured.” I find the sentiment to track, or acknowledge, change compelling, and I also like the way that Rushca did not hide the camera’s lensing with the construction of the panorama. Technically, it’s worth noting that Ruscha’s images work as a linear panorama because they are scanning a single plane - the building facades - and as you look deeper into the perspective in the images, the connections start to break down. Another image that works as a panorama, but is constructed quite differently is Art Sinsabaugh’s Railroad Crossing #24 - ⅔, 1961. This image tracks the flat midwestern landscape using a large format camera and a long (telephoto) lens and then becomes a linear panorama by cropping off the top and bottom of the image. This creates an absurd flatness, and an ability to compare the relative size of objects that are quite distant from one another that begins to reveal a connectedness that I would like to have in my own panoramas. This connectivity is also emphasized by the lack of any separate frames being artificially tied together. The last panorama I’ve been looking at is a stereoview panorama from the top of Telegraph Hill in San Francisco in about 1867 by Carleton Watkins, see in part here in Figure 1 and 2. The images are unique in that they are made to be a round panorama of the city, but are meant to be seen separately (only 16 and 17 seen here), and in 3D Stereoview. For me, there is an intriguing compromise made here between the spatial experience of a place, and the time needed to switch to another stereoview, and the imagination required to place oneself in the next image, relative to the last. I’ve provided a crude combination of the above images below (Figure 3) to make it easier to see how they line up. While there is still quite a bit of work to do to combine the technical functions of these historic images into my panoramas of forests, I have made some new images that start to stretch the tools I have at hand. (Figures 4-7). I have learned that the longer my lens, the better a linear panorama I can achieve, and I have also tried to stretch the limits of Photoshop’s canvas size by manually combining multiple iPhone panoramas together, which represents an entire stretch of recently colonized farmland. The lens makes for a more legible panorama but also introduces strange variances in the color consistency of the combined image. These tests are continuing to get closer to the newly-imaged forest Aaron and I have been talking about, and I am excited for the next experiments. Aaron I continue to consider the scientiartistic coproduction of reality and its subsequent perception by practitioners and viewers. This entry is inspired and informed by the overlap between Eric’s and my shared interest in and practice of photography and woodworking We have been considering how we can simultaneously see and know individual trees while visualizing and understanding entire forests. At the same time we have been exploring this question through different kinds and manipulations of panoramic photographs, we also have been thinking about transformations of trees and forests into material (“wood”) from which we create and envision abstractions of trees and forests in aesthetic and utilitarian objects. In our research, we came across a fascinating illustration from the Encyclopédie Méthodique de la Marine (ca. 1783). Here, oak trees are envisaged as a series of cuts - analogous to cuts of meat - each of which would have a particular use in the building of a boat. The creation of a boat (or a fine meal) not only takes materials but also takes years of practice. The end result needs to float, but the addition of artistic design and fine craftsmanship can transform a utilitarian object into something entirely different. In this transformation, we gain an objet d’art but we often lose the intimate connections with our understanding and appreciation for its source materials. From a tree to a boat. Top left: Western red cedar (Thuja plicata), H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, Blue River, Oregon; Bottom: Kayak baijitun (白暨豚), constructed of three different kinds of cedar (Western red cedar, Alaskan yellow cedar, Eastern white cedar) and black walnut; Top right and center: details of bow, cockpit, and stern of the baijitun. Red cedar designed by evolution; kayak design (North Star) © Rob Macks/Laughing Loon; kayak construction by Aaron M. Ellison; and all photographs © Aaron M. Ellison. Can these connections be recreated only with photodocumentation, and what is the additional role of Benjamin’s “tiny sparks of chance” in triggering awareness and implied transformations?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |