|

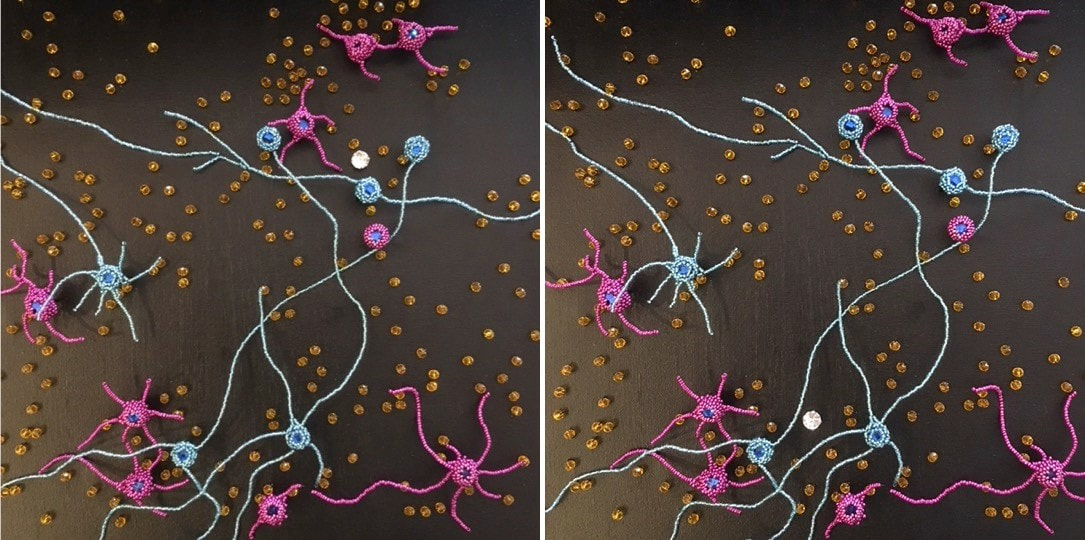

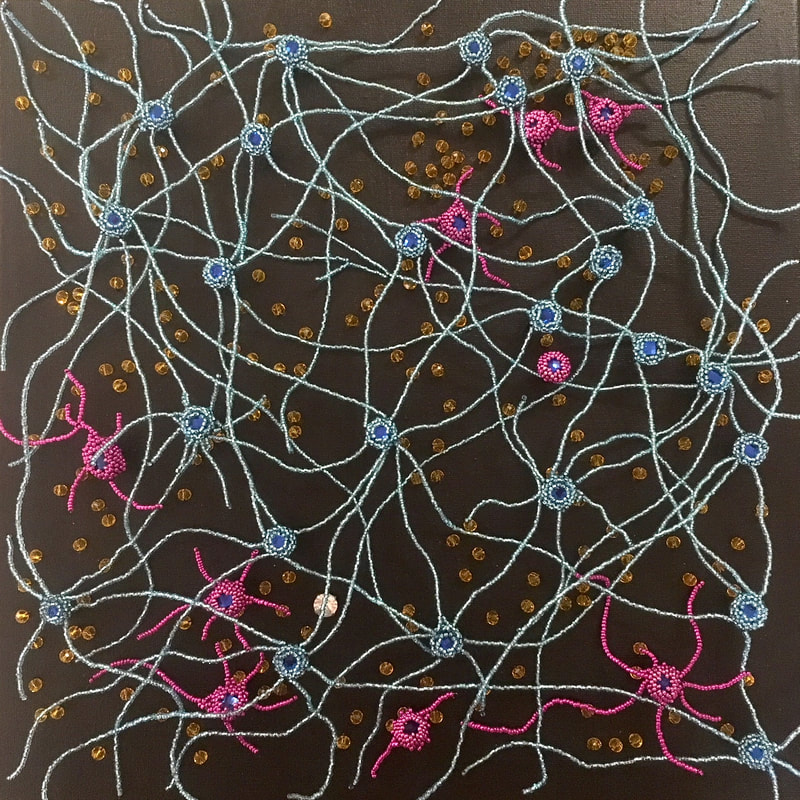

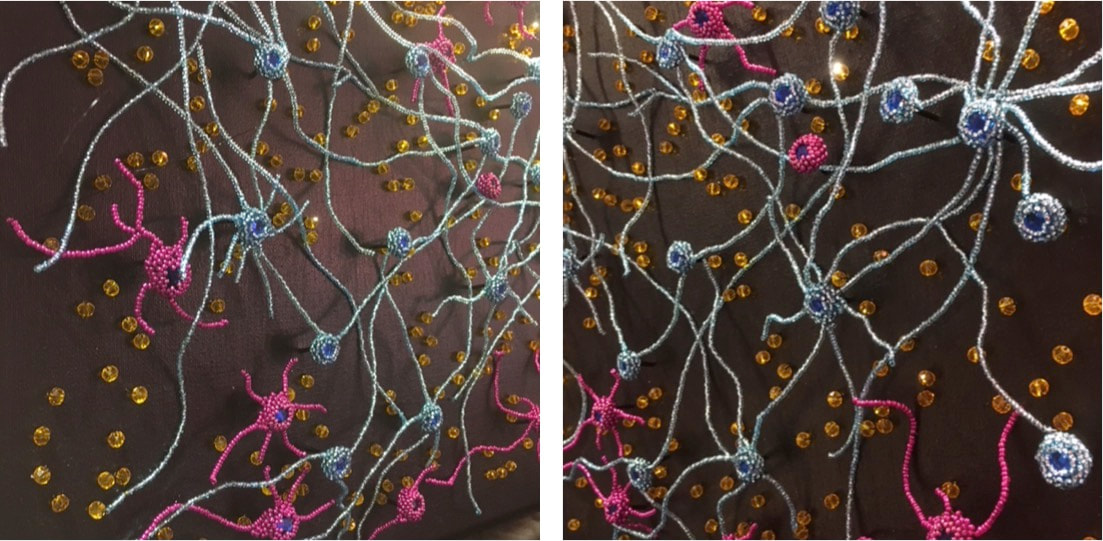

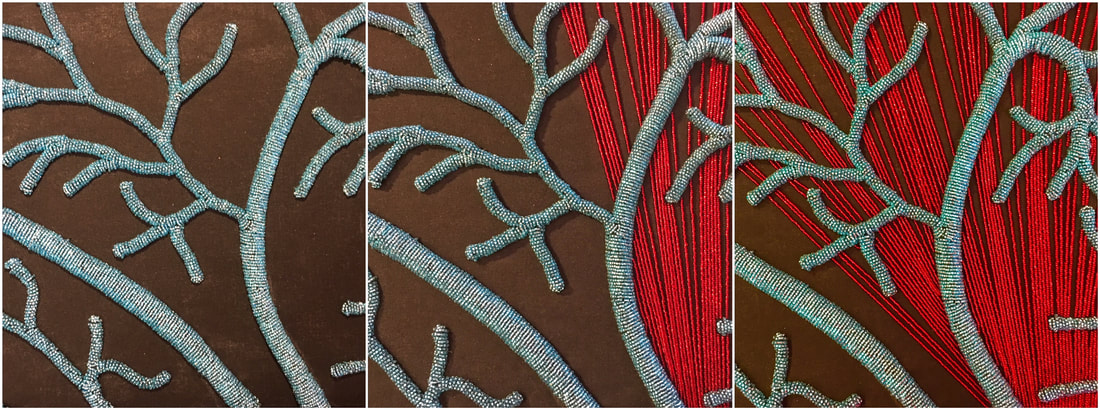

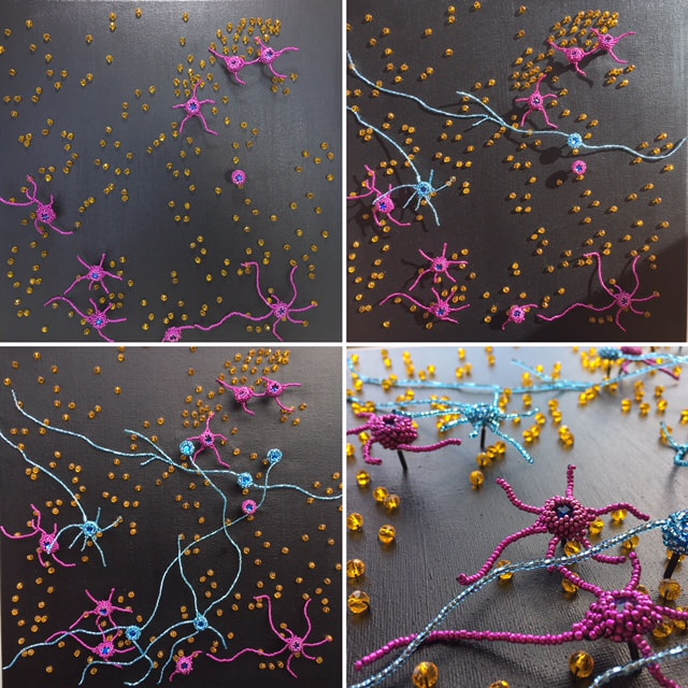

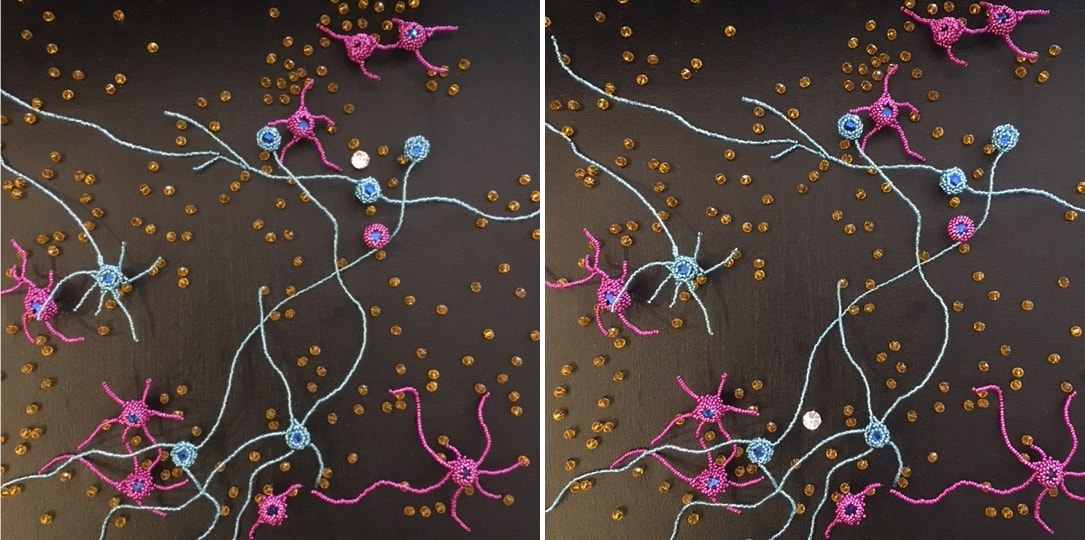

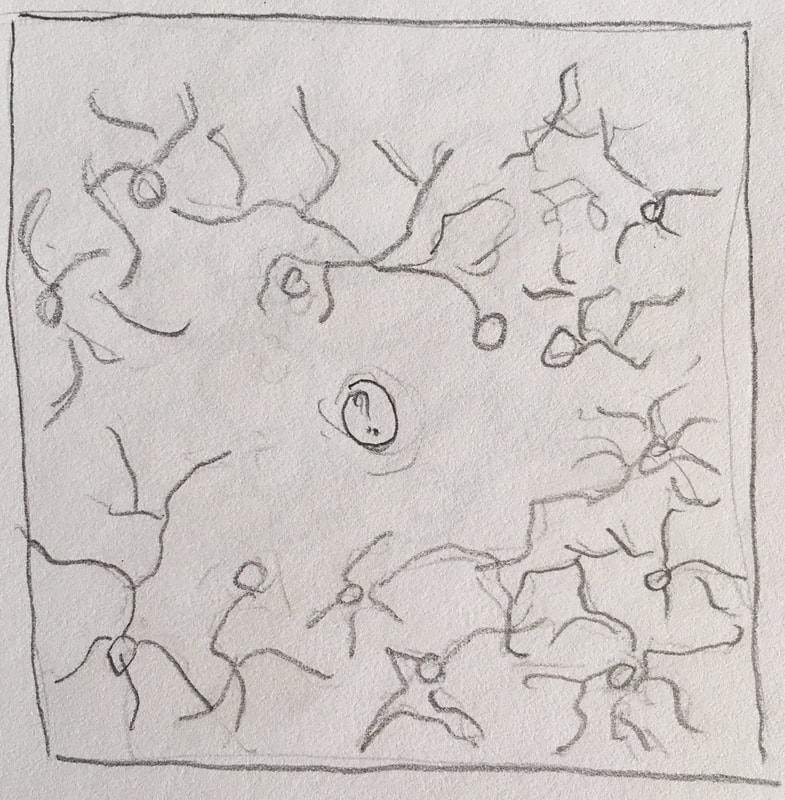

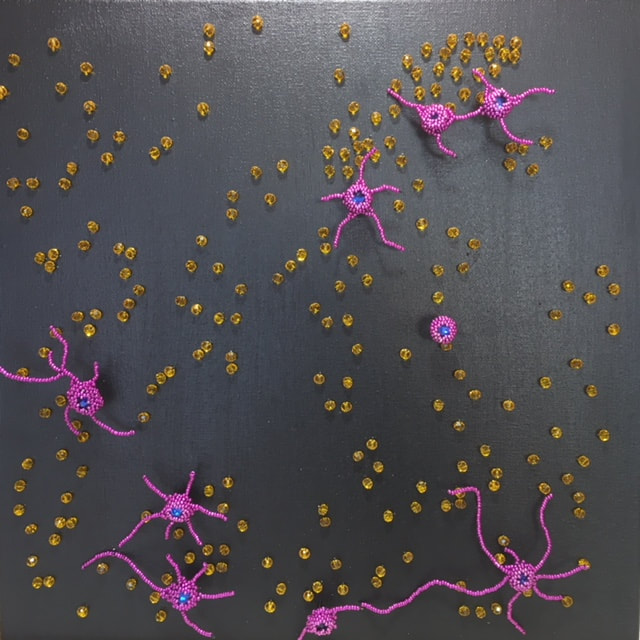

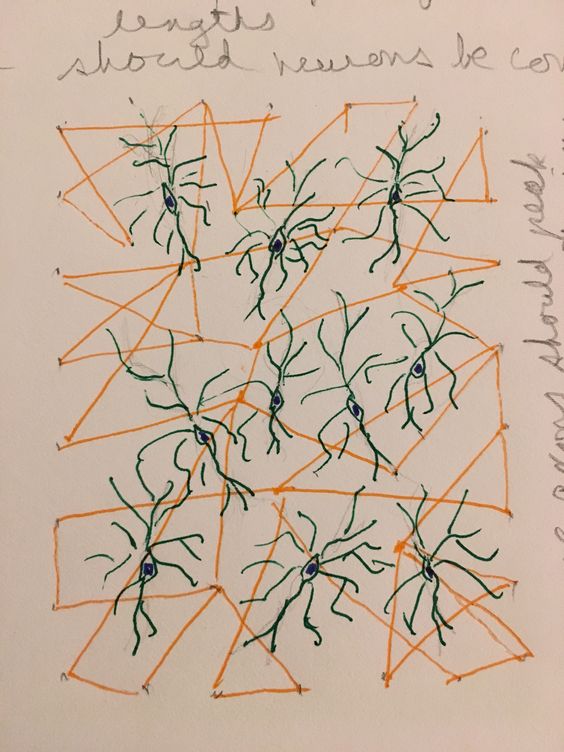

Yana The SciArt Residency is over and it is a good time to look at where it led me. Before embarking on this journey with Darcy, I had a few vague ideas that I wanted to coalesce into 1-2 projects. A lot of people talk about art being both a playground - where we can let go of our daily inhibitions, and a way of expressing our true feelings. The exact meaning may not be clearly evident to others, but at the end of the day, the art allows us to at least get something off our chest. Due to some personal circumstances, I was feeling lost. I felt like I am losing a big part of what I consider to be my identity. I was losing a sense of self. Before starting the program, I did some brainstorming, took a trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and came up with a couple sketches for a potential new project. As I have written in a previous post, I use my sketchbook only to jot down the "bare bones" of a project, which come down to the general composition and some ideas on engineering the necessary structures. I wanted to portray the idea of a dense network or forest, representing the complex composition of a large city. Although I have lived in New York for the vast majority of my life and I love it, sometimes it can be a bit difficult to navigate. And I don't mean geographically. When Darcy and I started working together, I explained my idea and suggested that we use an image that came from my lab work for inspiration (shown mostly in red). Darcy manipulated the original image in Photoshop, resulting in a novel set of colors (mostly in light blue). Her adaptation also emphasized the texture of the image, giving the neurons more volume. Beyond creating the network, initially I also wanted to emphasize the constricting environment by putting a layer of string art on top of the neurons, depicted in orange in the original sketch on the right. But when I finished beading the neuronal network, I realized that it would be too much and ended up shelving that idea for another project. One of the original sketches had a circle with a question mark in the middle. It took me a long time to decide how to portray myself among the challenging environment. I wanted it to be a small entity in this sea of connections, yet it needed to be different enough from the rest of the structures to stand out. Finally, I decided to follow the theme that I used in "Hope" and incorporate a single white jewel, slightly hidden below the rest of the network. This would allow me to put a positive spin on the sense of feeling lost. Finding the right place for the white jewel took some time and playing around. About midway through the project, I felt like I could not proceed without making this decision. Especially, since a lot of the blue cells and connections needed to be positioned on top of it, it had to be put down pretty early on. After letting it stew for a couple weeks, I ended up going with a gut-based decision. It felt very unlike me. Once I placed the white jewel on the bottom and slightly off center, I started layering on the neuronal connections. They would represent the jungle gym that we need to maneuver in both the city and life in general. I wanted them to be very tangled and interdependent, but elegant at the same time. Outer complexity leads to inner complexity, yet our brains can sort and organize information in an interpretable manner. It was particularly challenging for me to start filling in what I considered to be empty areas. The network was physically growing in density, making it very difficult to thread the wires from cell to cell. Initially, I was planning to make the longer connections using thread, but ended up using wire throughout the project, making it more sturdy and uniform. Uniformity of technique gives me a sense of peace. To fill in the empty spots, I had to populate the landscape with connections that did not correspond to the original image. Despite this being a creative process, introducing elements that are absent in the original always leads me to a sense of internal conflict. It almost feels like falsifying data. But I followed the patterns that could have formed in nature and hoped that the connections would arise organically. There can be no limit to labyrinths and tangles, but at some point a project must come to an end. So after creating what I considered to be a sense of balance, I brought it to a conclusion. This project has made me step out of my comfort zone in many ways.

Darcy

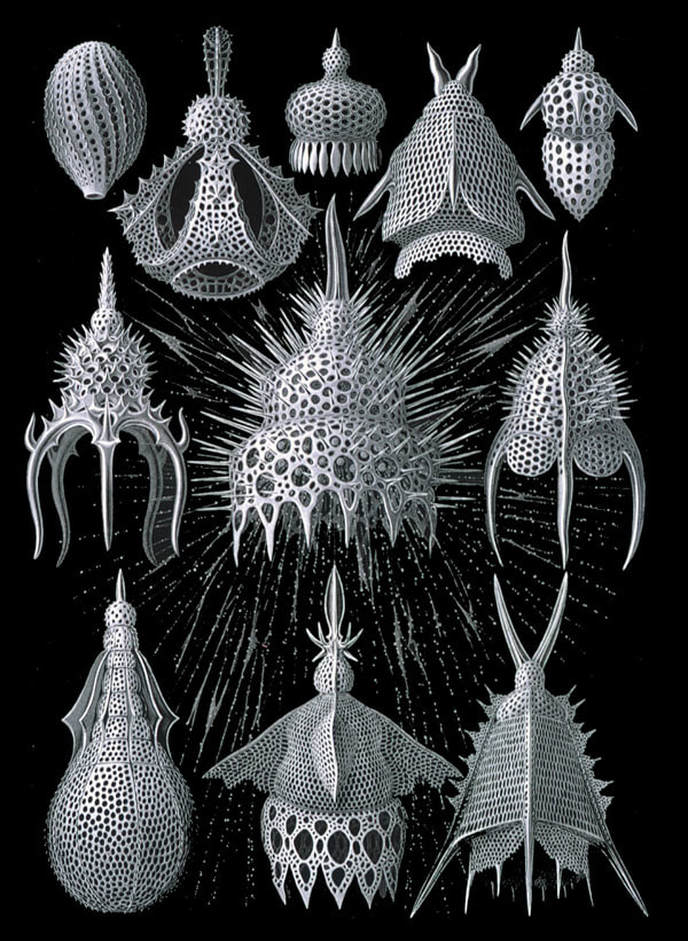

This residency has been inspiring and artistically productive for me. In broadening my understanding of SciArt it has pushed me to explore and redefine the connections my art practice has with my love of science. I have thoroughly enjoyed working with Yana and we are already planning another project together. There are endless avenues we could pursue together with neuroscience images and their expression in visual art. During this residency I have wandered through some great books, some for the second time such as Ernst Gombrich (“The Story of Art”), that I have been reading on and off for years. Relatively recently I have come across, Eric Kandel (“The Age of Insight”, “Reductionism in Art”) and Robert Sapolsky (“Behave”). My last two reads were the rediscovery of Alexander Von Humbolt in the passionate voice of Andrea Wulf (“The Invention of Nature”) and then, “The Age of Genius” by a favorite author, AC Grayling. All of these brilliant writers and many more have influenced my ideas and found their way into my own writing repeatedly. Then there are the artists, who I don’t refer to as often in this blog series because I was really grappling with how science and art inform each other in the less obvious ways. However, they need to be mentioned here too. How can I choose, there are so many...Ernst Haeckel, Paul Klee, Joan Miro, Picasso, Franz Kline, Brice Marden, Mark Tobey, Joseph Beuys, Cy Twombly, Arnulf Rainier, Richard Serra, Eva Hess, Sol LeWitt, Lee Bontecou, Frank Stella, Thomas Muller, Gerhard Richter, Julie Mehretu and, and, and… The truly interesting thing is to try to remember what my thoughts looked like before my encounters with the rich worlds of science, art, and ideas. Impossible, even though I “feel” like the same person I was at 16 years old or even 10. The intricate reordering of the mind that happens when we corroborate our worldviews with others is so pervasive that it is impossible to tease apart. This is a collective understanding that emerges from our social nature, our ability to learn from and influence each other. I value this above everything. It is the hope for the future. To be clearer in our understanding of ourselves, our species and the gorgeous complex living plant to which we are completely connected and dependent. This residency has fulfilled many of these desires and concerns. Yana is an accomplished neuroscientist with the rigorous mind of a scientist and also practicing in the more nuanced inquiry of art. Our collaboration has brought up ideas I have not thought of before and a rich body of imagery that Yana has provided in her microscopy work. The most recent images she has shared with me show cancer cell membrane markers. When I have time to get back into my studio, I want to play with all of the ideas these images inspire. In conclusion, I want to mention that none of the artists I have listed above except Ernst Haeckel do SciArt. I think this is because I look for artists that express the most fundamental desire to understand human perception and our expression of the unique yet still collective internal worlds we all possess. This residency has encouraged me to look deeper into the SciArt community for ideas and understanding about the highly varied work that comes out of this burgeoning field of art. Thank you all for this experience.

0 Comments

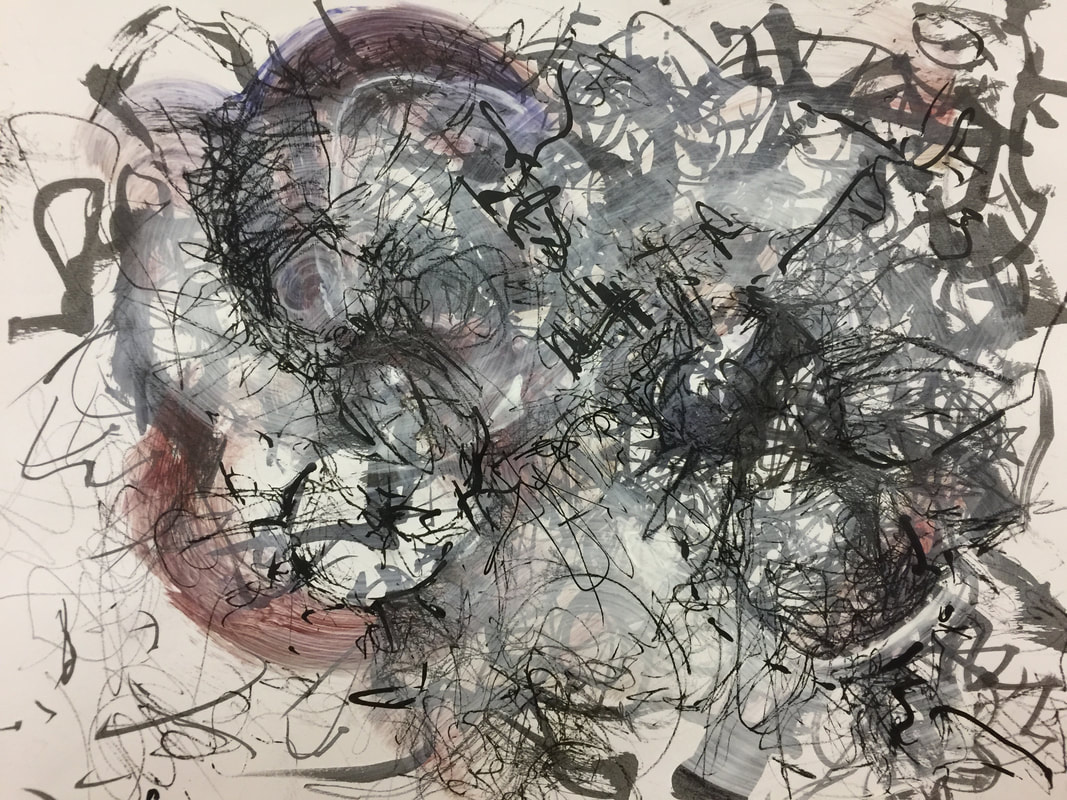

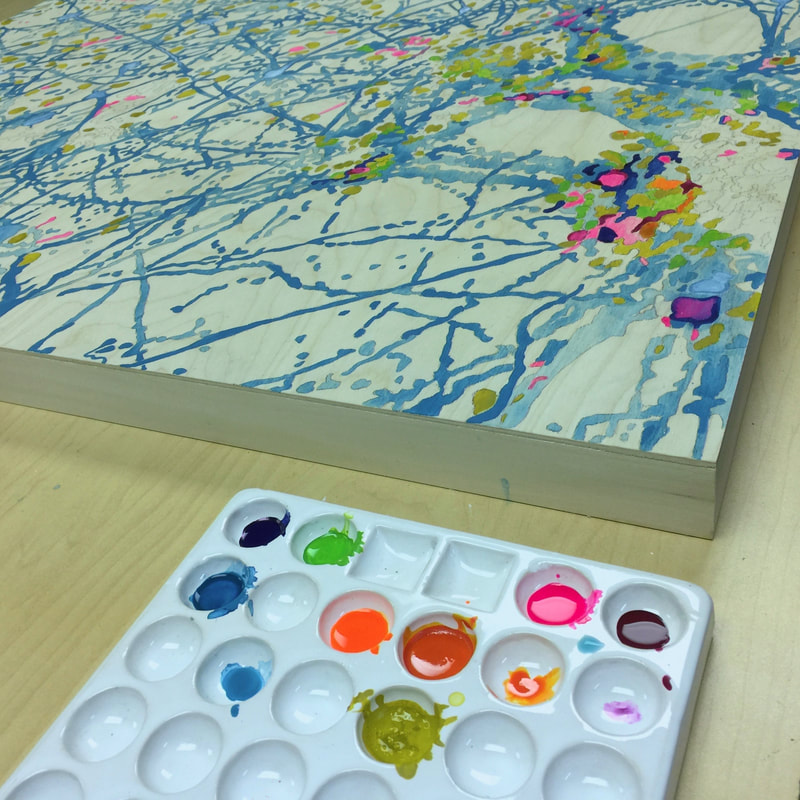

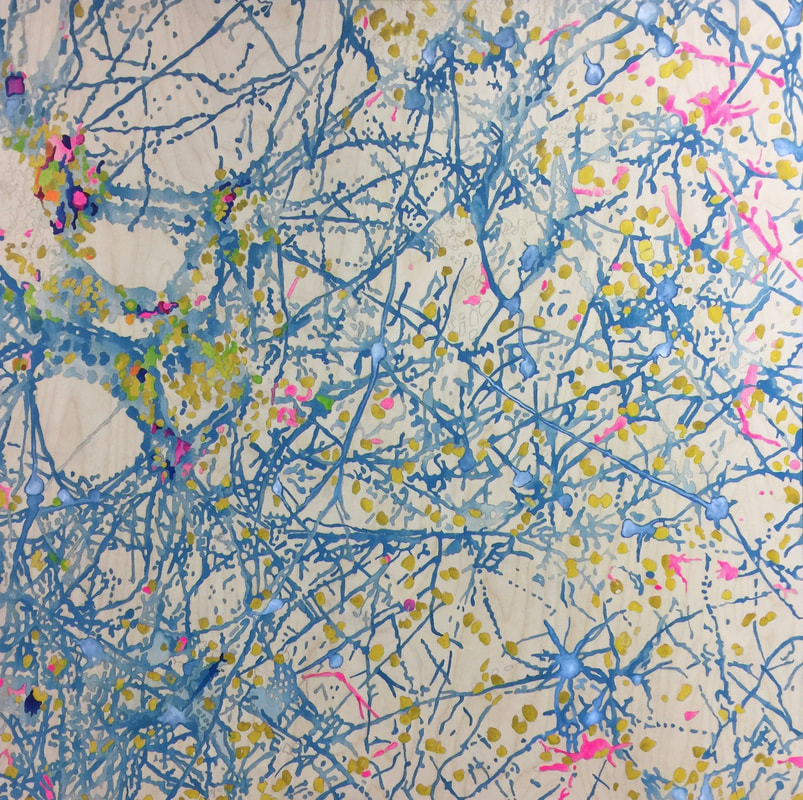

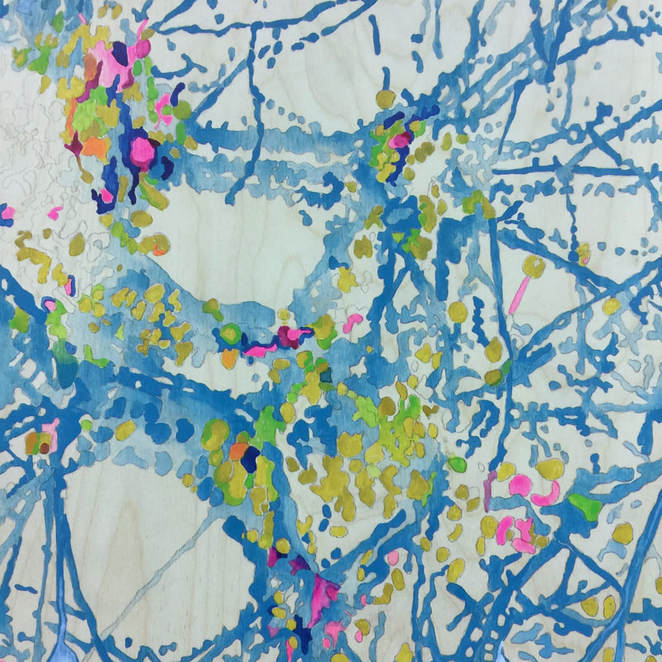

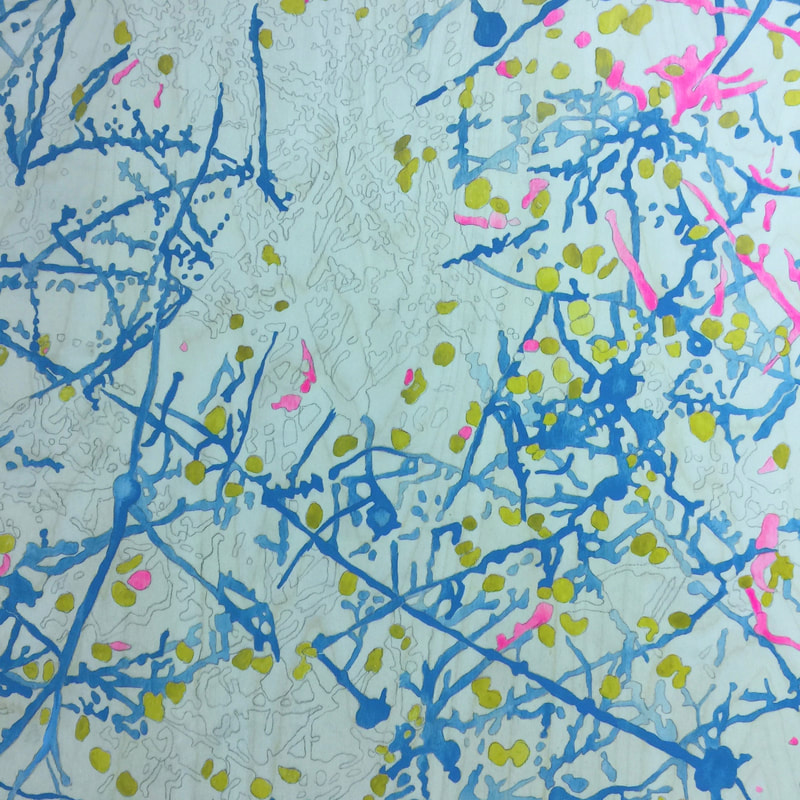

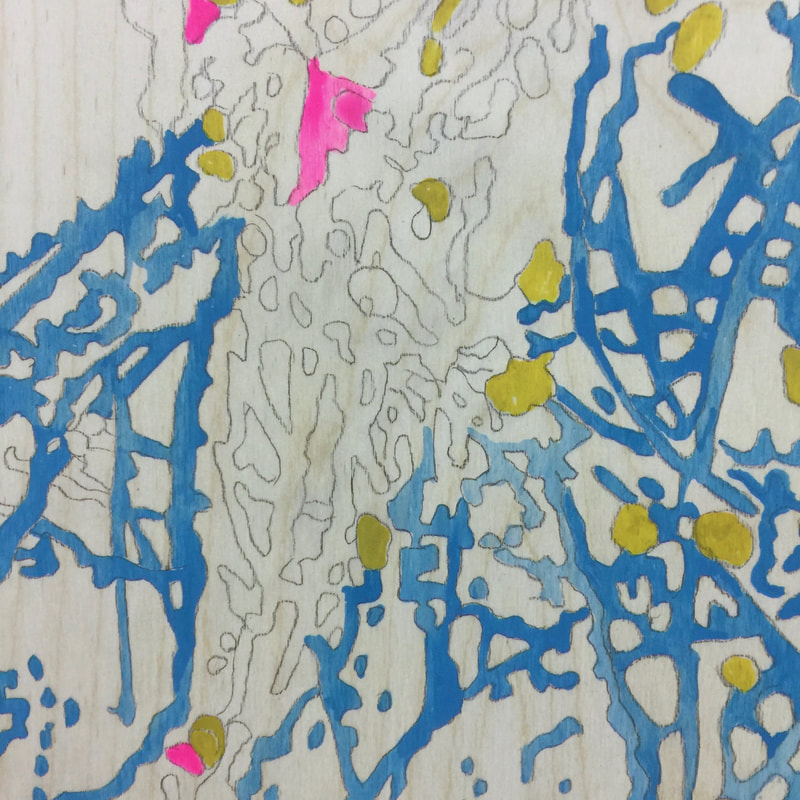

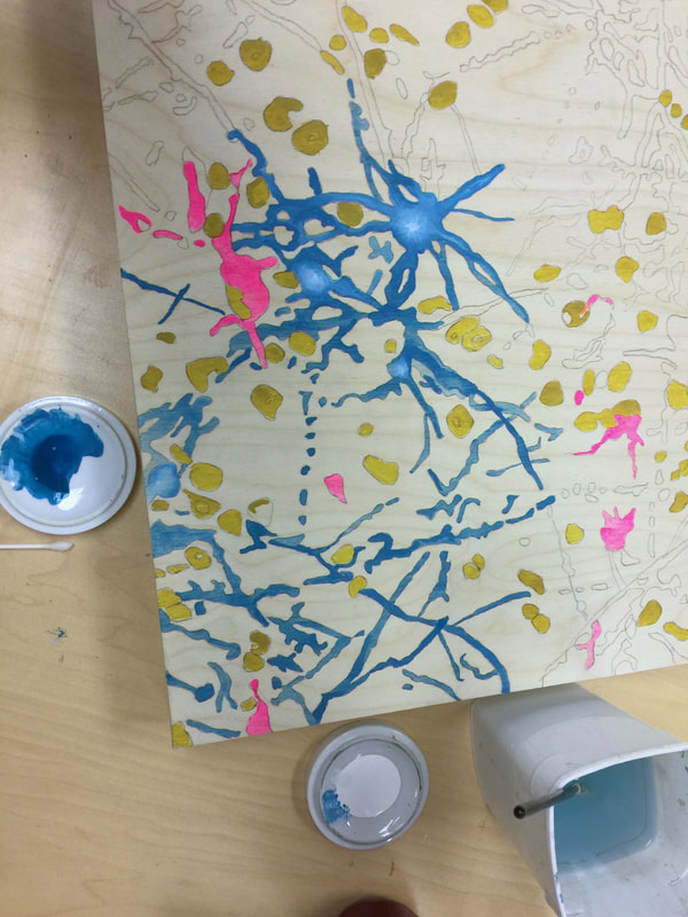

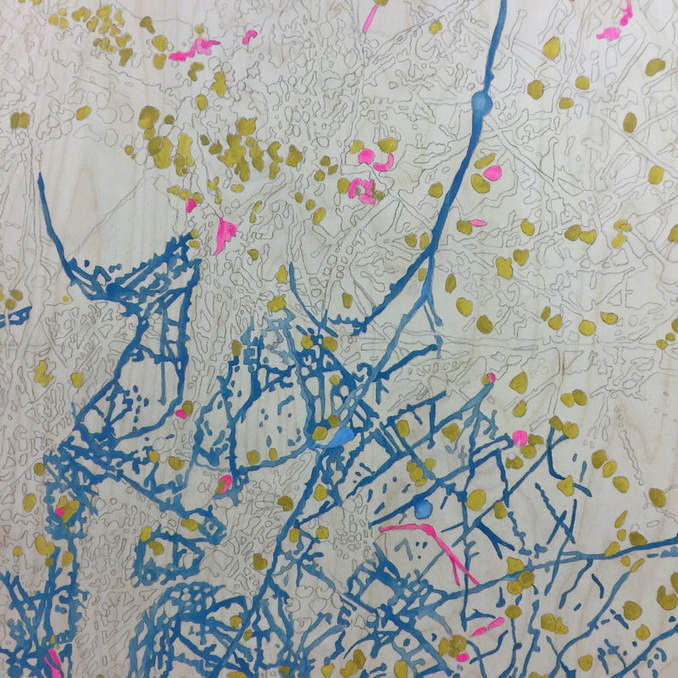

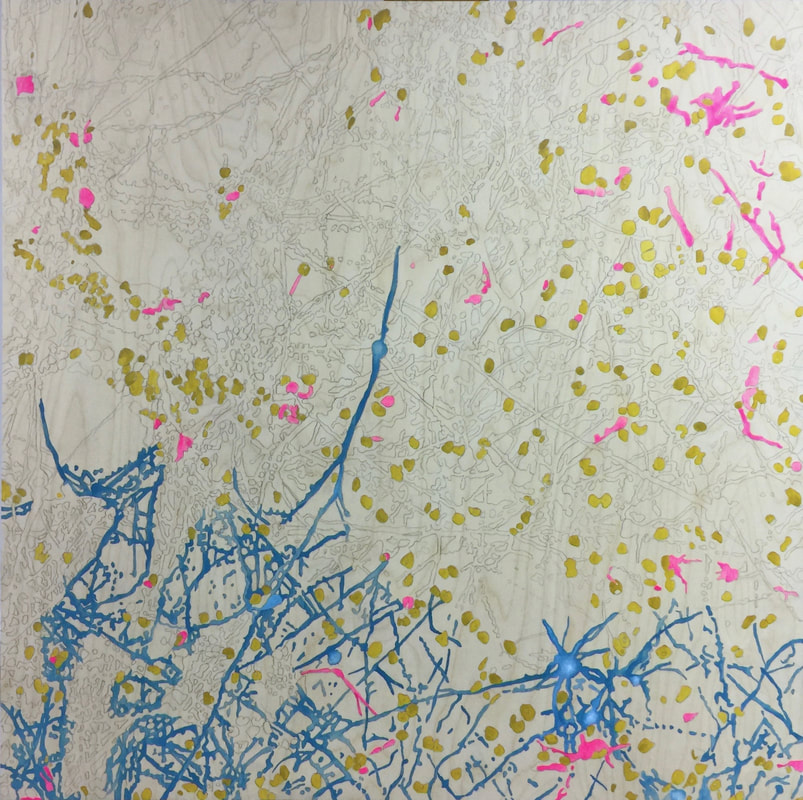

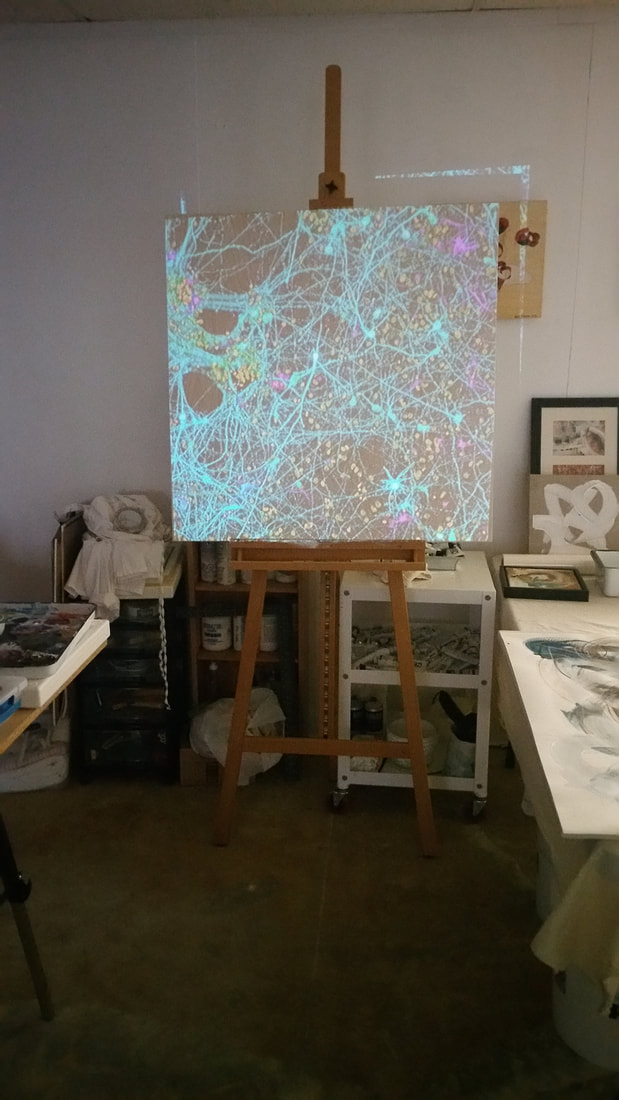

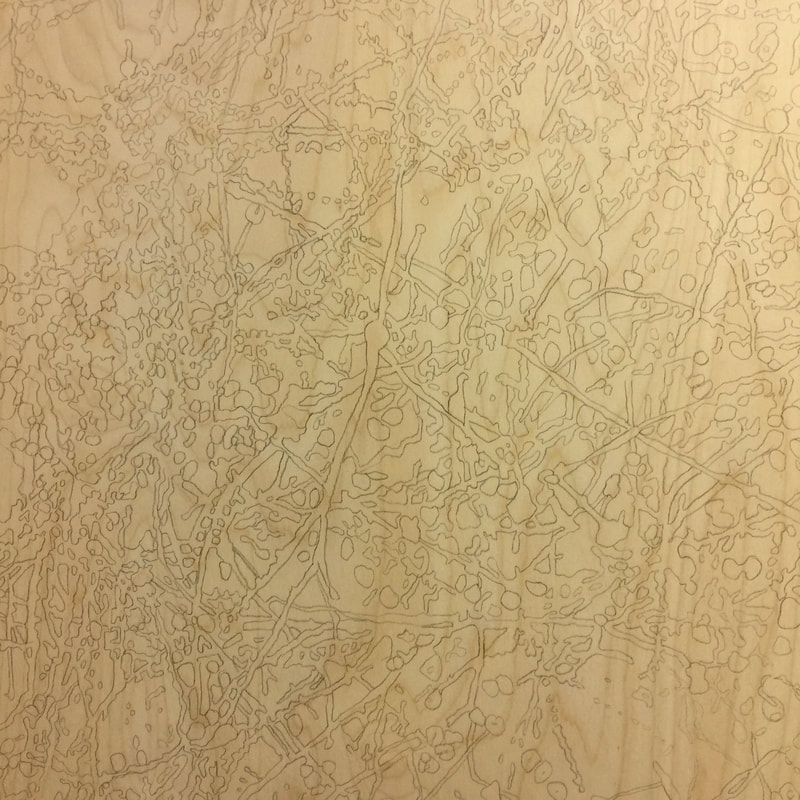

Yana Continuing in the theme of balancing the structured scientific method and free play (as Darcy writes about this week), I keep struggling with letting go. I strive for scientific accuracy, yet sometimes you need to decide what to keep and what to leave out to gain clarity. Sticking to the original image makes me feel in control, while venturing off with making my own imaginary connections (which are totally possible in this context) feels like throwing in the towel. And then balancing all of this with the concept of composition and making the image visually pleasing… Letting go is difficult… In science, “bias” is a dirty word. The same goes for Photoshop. Altering data and being selective in what you pay attention to leads to direct risk for being very subjective and failing to see the real picture. You can get carried away with trying to fit everything you observe into a picture that you have already formed in your mind. It is quite dangerous. Darcy previously wrote about creating models from of observations. While it may be important for understanding difficult concepts, you cannot grow too attached to your model. Unfortunately, there is also a factor of consistency. A scientist may keep publishing papers proposing a certain model of a disease or natural phenomenon. And then suddenly they come across a piece of evidence that contradicts their initial thinking. What do you do in such a situation? Well, if you publish the new data as it is, you will be accused of being inconsistent, which will make people question all of your research. Who would want to do that to themselves? So people try to find a way to slightly alter their models to accommodate for new evidence. But is that the right way of going about it? When I was in graduate school, my advisor used to jokingly say that bias is a sign of knowledge. That it allows you to use your experience to observe what otherwise may not be obvious. While it may be true that a trained eye will see what others would not, the “beholder’s share” needs to be consciously controlled. So where does this lead us and how is it relevant to art? How do we gain clarity and not leave out important details? Who is best and judging what is important and how will you know if something important is missing? Darcy So here we are in the last week of the residency. I am ready to start a new painting and plan to explore “Where’s the Party?”. This is another collaborative image of Yana’s and mine. This will be the sister painting to “Mapping Manhattan Revisited”, done in a similar way in order to observe the differences in process and outcome. I will start by projecting the image on a 36” X 36” wooden cradle, redrawing the image in graphite, then painting directly onto the wood with an array of bright inks in order to recreate the pattern. I will continue posting the results of this project and others on my personal blog, darcyelisejohnson.com. I have come to enjoy painting when there is a procedure to follow even though I will always produce some artwork that is spontaneous, expressive and unpredictable. It is wonderful to lose myself in an abstract image but there are times when this process of making art ends up in a mess of chaotic ideas. Even so, the mess yields its own wisdom and provides a pathway forward. (See Image #3) A structured method pushes my creativity in a different way than the more intuitive paintings and drawings. It provides a framework that holds me in and anchors me to the image. I am able to compare the results of a particular process over a number of artworks and gain valuable insights. I can play inside the boundaries I have set up for myself when I use a planned, stepwise method and discover the consistencies and anomalies in the results.

I have often thought that part of my attraction to science is the structure it provides for new and more complex insights. Scientific thinking gives us a roadmap within which our imagination can act. It is a bit like fleshing out a storyline. The important revelations are in the details. Scientific methodology keeps us focused, organized and withholds judgment until the results are in. Then we bring our intellect and creativity to the results which at the very least, point towards the next step. There is another aspect of scientific thinking that I deeply value in my work as an artist. I glean ideas from the rich world of nature and try to understand them through art. I am doing art to study and understand both myself and the world and a rational method keeps me from spinning off the edge of the world in a flurry of colour and emotion. My two halves are always informing each other, the artist saying come on let’s play in the beautiful world and the scientist saying, well, let’s make this playfulness lead us to a richer place because we are bigger and stronger together. Yana The last two weeks have been a bit of a blur. After completing several layers of cells, I have hit a wall and decided that I needed a break from this project. I feel like it is the time to decide on where to put the clear white jewel in the background before it will be covered with strings of beads and become very difficult to access. Similar to my previous work, this jewel would represent hope. But I am stuck on deciding where it should be and feel like I can’t move forward without making this decision. In following multiple artists on social media, I have long been intending to adapt the practice of working on several projects in parallel. So I finally decided to leave “Mapping Manhattan” alone for a while and let it breathe. But of course, my hands cannot stay still. I decided to return to a project that I have put aside at the beginning of this residency and begin filling in the background… ...and I played around with digitally manipulating the current work in progress. This week I also attend a very inspiring talk by Amy E. Herman on “The Art of Perception” in the Art of Medicine seminar series at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Amy refers to herself as a “recovering attorney” and has a M.A. in art history. She uses art to communicate the importance of being objective on our observations and decision-making. Every single slide in her hour-long talk was a piece of art without a single word of text. And every single image had a very specific message for the audience. These included:

It was quite fascinating how so many questions could be simultaneously applied to both viewing art and treating patients and it made me think back to the core message I see behind SciArt - breaking the communication barrier between the biomedical community and general public/patients. While physicians may try to simplify their terminology and use visual aids to demonstrate complex medical concepts to the patients, the patients themselves may also need a more universal language. The patients often feel afraid of the physiological processes they do not understand and reframing disease into beautiful scientific, yet approachable images, may bring them a sense of comfort. This may be especially true for patients who recover. There is a wide spectrum of approaches patients take to communicate what they have gone through. Some are very brave in openly speaking about their experiences, but some still feel very stigmatized. I believe that scientific artwork can serve as an icebreaker for such difficult conversations. But does every piece of art need to have a specific message?.. Darcy So I have finished the painting. There is a mixture of loss and relief in finishing an intricate piece like this. The questions begin ... “when to stop?”, the... “what next?” and a burst of new ideas that have to be sorted and culled. The hardest question to feel good about is, “what was that all about”? Do research scientists ever feel that way? Well, maybe when things go wrong, but there is always the sense in scientific research that it is always “worth it”. Worth the effort. That it is meaningful and important for human understanding.

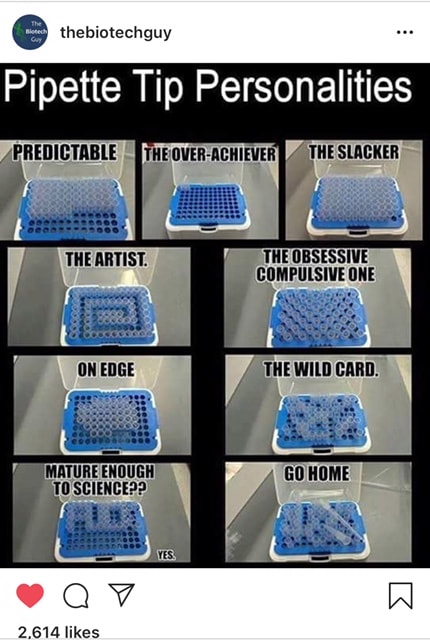

The sciences and their subsequent applications have made human life easier, healthier and more affluent than ever before. Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now gives reams of statistical evidence to this. Science has given us modern medicine, communication, travel, education, improved labour, cultural openness, and leisure, for the arts. The list is inexhaustible as science continues to help solve humanity’s problems. Maybe not fast enough to save our planet home from our thoughtless overuse but worth the effort to try. Better than the alternative. Does art have this same saliency in the modern world? Is art less important than it used to be, before the Enlightenment and the rise of scientific thinking? Do we, or even can we understand what the arts are really for? In this blog series, I have given a number of tries at an explanation. At least, the motivation to do art and the capacity to enjoy the art of others. However, when it comes to my own artwork I am often left mute as to any greater purpose other than to satisfy my own curiosity. This is probably sufficient because it keeps me open, learning and discovering. Many scientists are motivated but just this urge. The desire to know and then, to know more. So in this way, there is equity between the arts and the sciences but I’m not sure that this value extends beyond the communities engaged in scientific or artistic work. I feel that the arts get lost in the noise of commerce. Does science also suffer from this? Science is institutionalized by universities and funding agencies that make it more efficient, rigorous and protected. More and more, the arts are being unhinged from their original institutions. What is the consequence of this? Does it matter that so many of us are out there drumming without the rest of the band? A modern problem allowed by leisure and to some extent, wealth. So...only questions? That is what finishing an artwork does to the artist. I want to just throw this painting out there into the world and with it, some of my inevitable disappointment in its manifestation. I want to discover what others see in it...if anything. Is it meaningful or beautiful? Does beauty matter? Does anyone care? Am I the only one being fed in this process? Is the world making me feel this way or is it simply the ancient struggle of the risk taker. Reading Steven Pinker reminded me that our perception of beauty may be related to our positive response to order as opposed to the more disturbing qualities of chaos. In the living world, we have circumvented entropy for as long as the sun has shone. Time and the sun’s energy drives the increasing complexity of life in an orderly way. Even if we don't survive as a species, other life forms will, until our sun’s energy alters dramatically. We exist in the self-organizing world of nature, which is unusual in the universe where the normal trajectory is towards disorder or entropy. And so we may have evolved to recognize order as a positive part of the process of life and our own survival and then, eventually named it beauty. Understanding our world is what being human is about. What are these recurring patterns? Why are they around us? How is it that we can even think about them? Is this the beauty we all seek, in science, the arts and each other? Yana As I have mentioned before, most of the time art and science coexist in my brain. While the setting, such as being at work vs. at home, may dictate which side dominates, the other side rarely shuts off. In my scientific career, I have spent over 13 years using microscopy to acquire and analyze data. When I look at fluorescence microscopy images, they always tickle my aesthetic side. The opposite is also true. While I use art to (partially) shut off rational thinking, I cannot prevent my left hemisphere from taking part in the decision making process. Throughout the time I have spent so far on making this piece, I have been feeling conflicted about the purity of my technique. While I tend to refer to my work as “mixed media” (for the lack of a better term), I really don’t like to mix my methods. For example, sewing the large yellow rondelle beads directly onto the canvas went against my usual approach of using small seed beads on a wire. This “noisy internal dialogue” interferes with my sense of flow. Where do you find the balance of staying true to your style and not being afraid of learning new things? Is it an excuse for not taking the risk of expanding your horizons or does it really feed into defining your identity? This week, I came across a funny picture on Instagram showing different approaches people take to pick up pipette tips from a box in the lab. Although I have seen something similar before, it still made me laugh. I realized that while I certainly cannot call myself a particularly neat person, I always use the so-called “predictable” method (as opposed to the “artist”). When I need to use a common box that was used in any other way, it causes a bit of a visceral reaction. The same probably goes for my art. It needs to follow a smooth, repetitive and possibly predictable process to be satisfying. And so far that is mostly what I have been doing. As Darcy mentions in her entry this week, the original image is too complex to be fully rendered, so I need to be selective in which cells I decide to make. My typical method involves stringing beads on a thin wire, but given the complexity of the network, I have considered doing some sewing of the thin processes as well. So far that hasn’t happened. It has been particularly challenging to create the long connections between separate cell bodies using wire, but I am trudging along. Sooner or later I will probably give in and switch to needle and thread, but then what’s more important - accurate recreation of the image or a sense of unity? Darcy

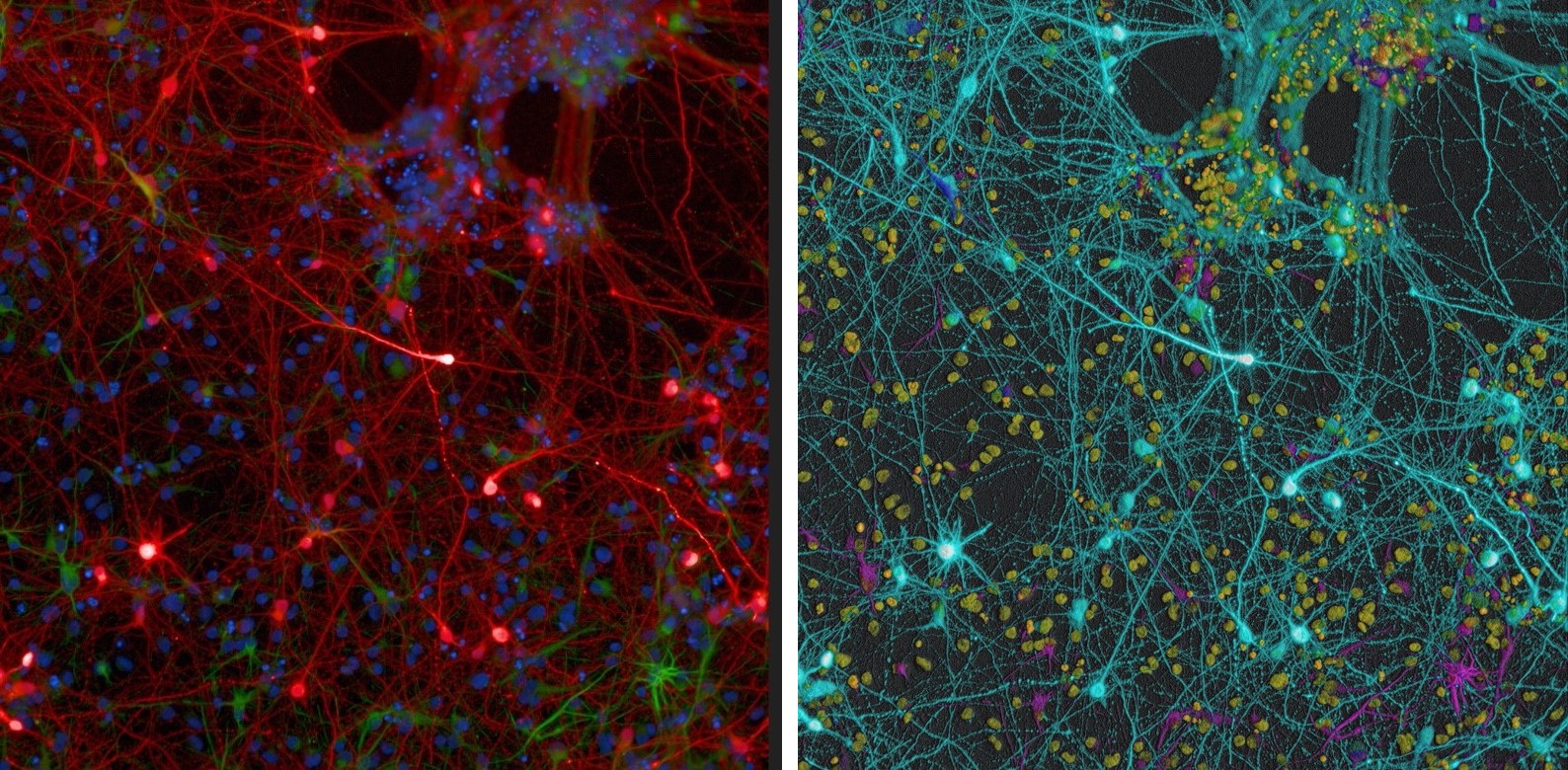

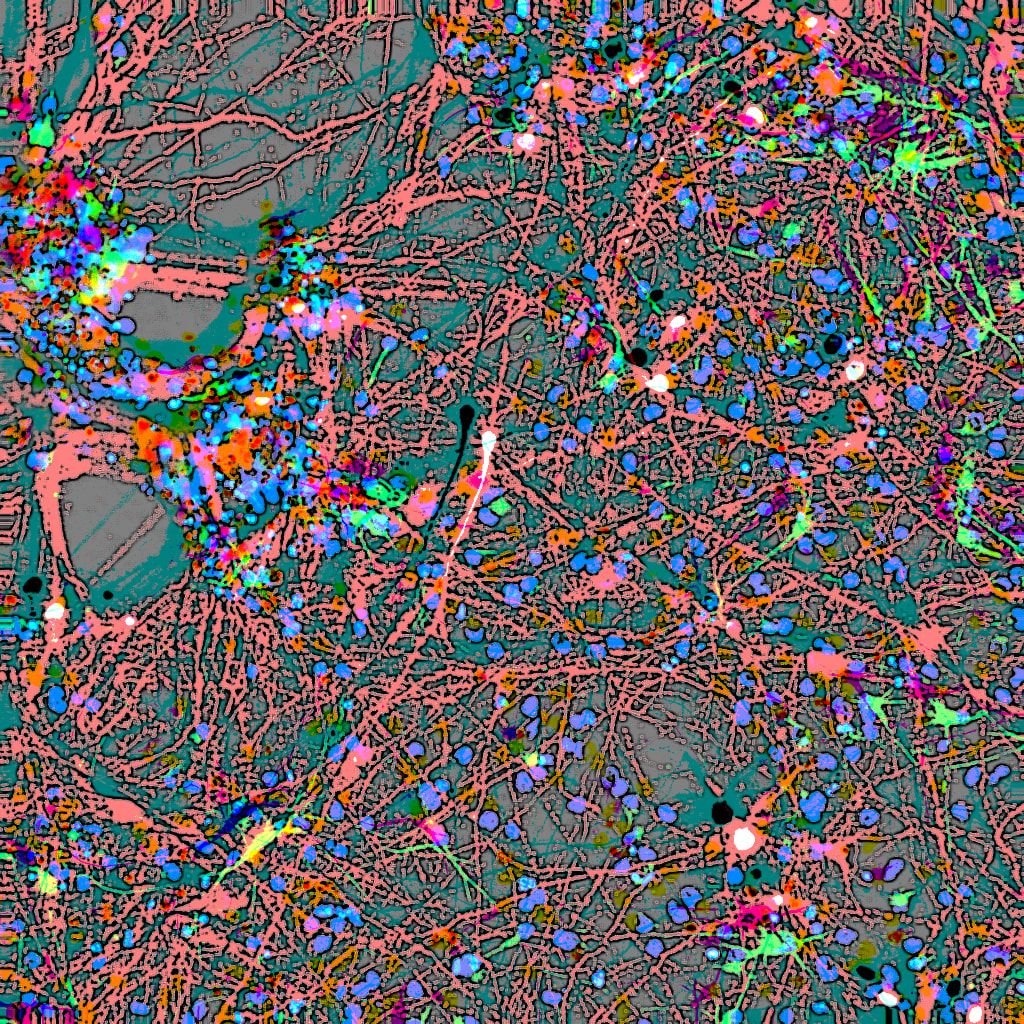

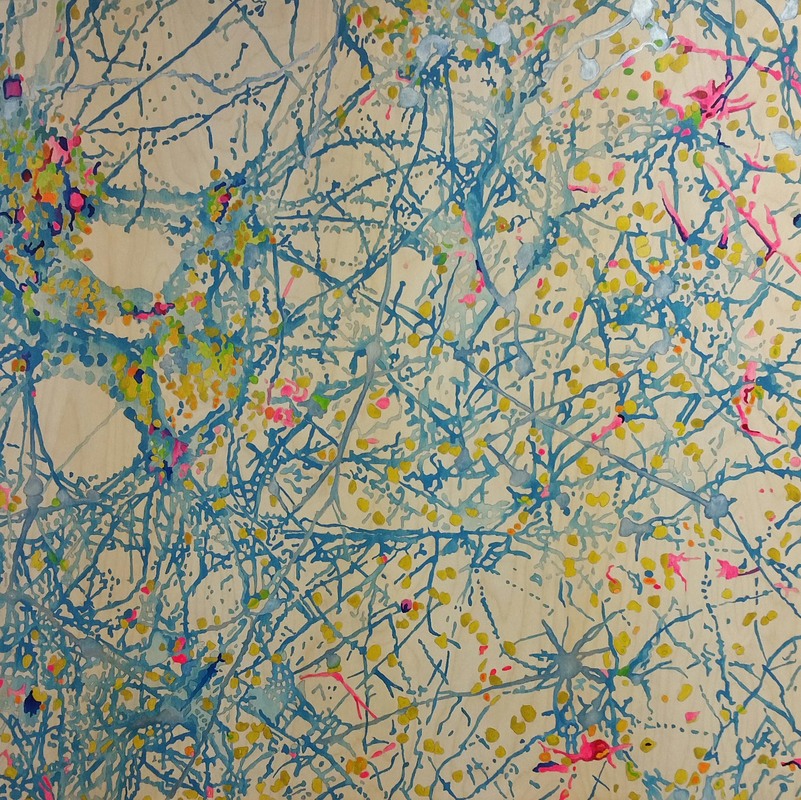

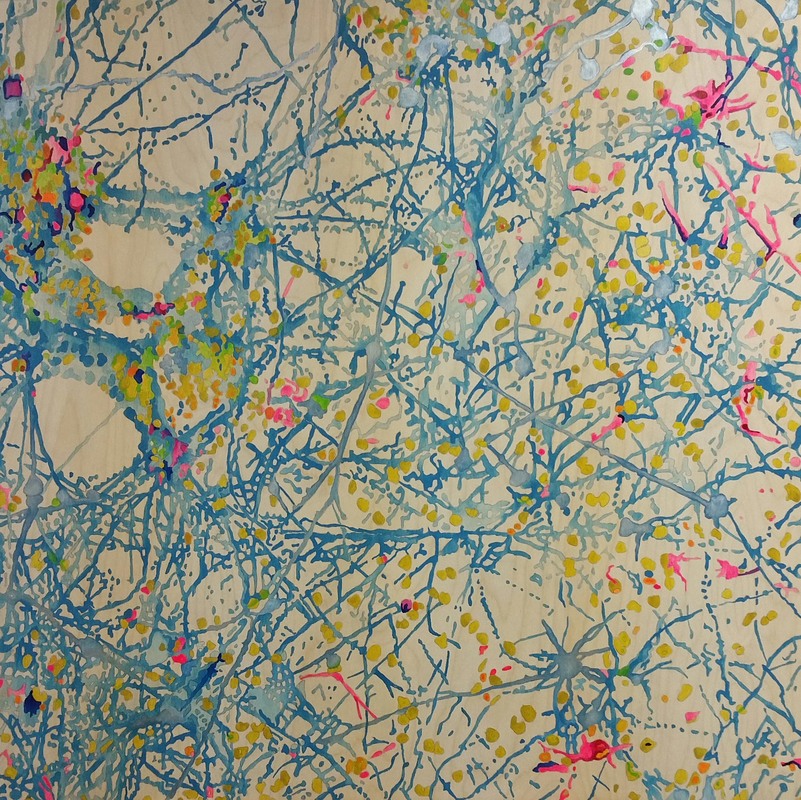

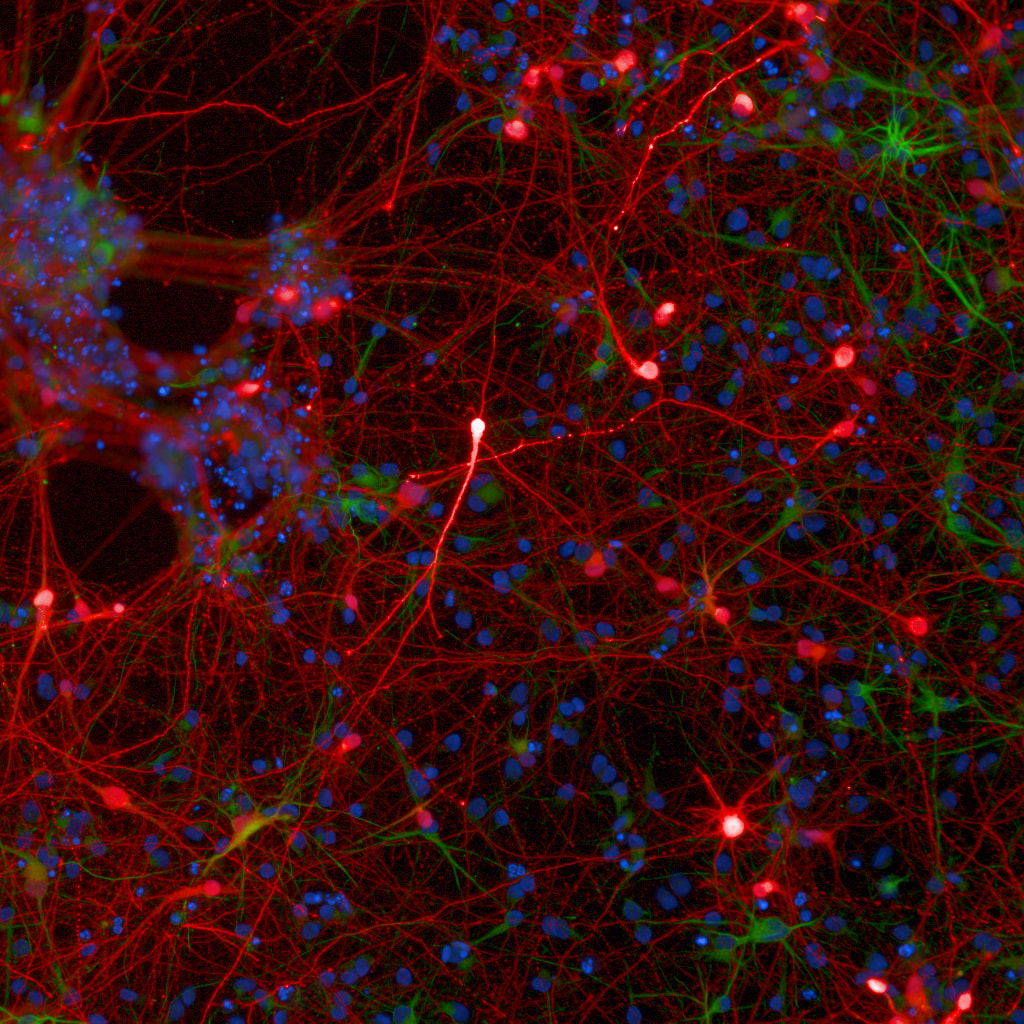

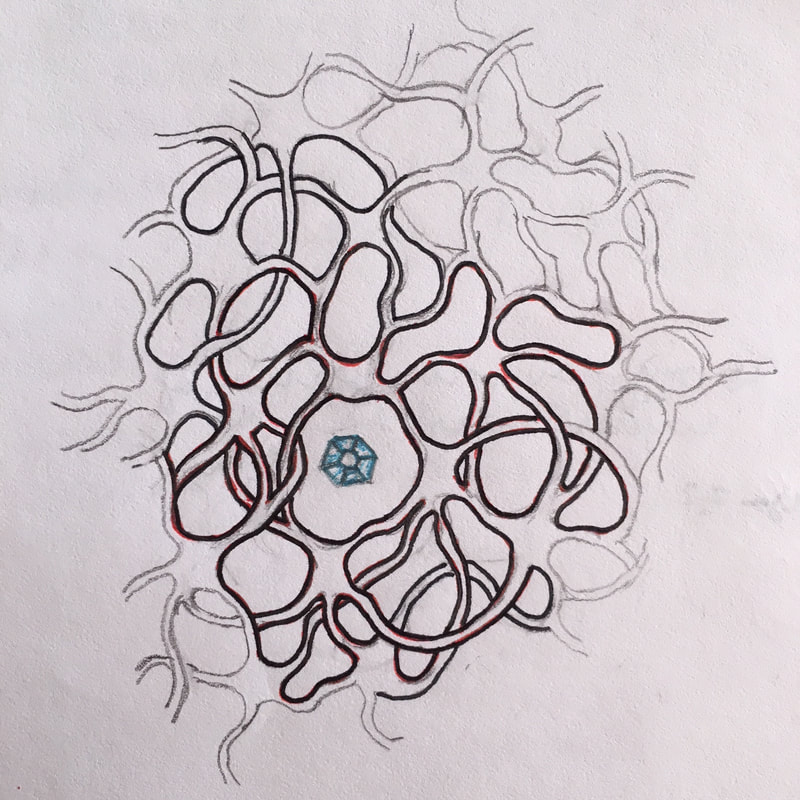

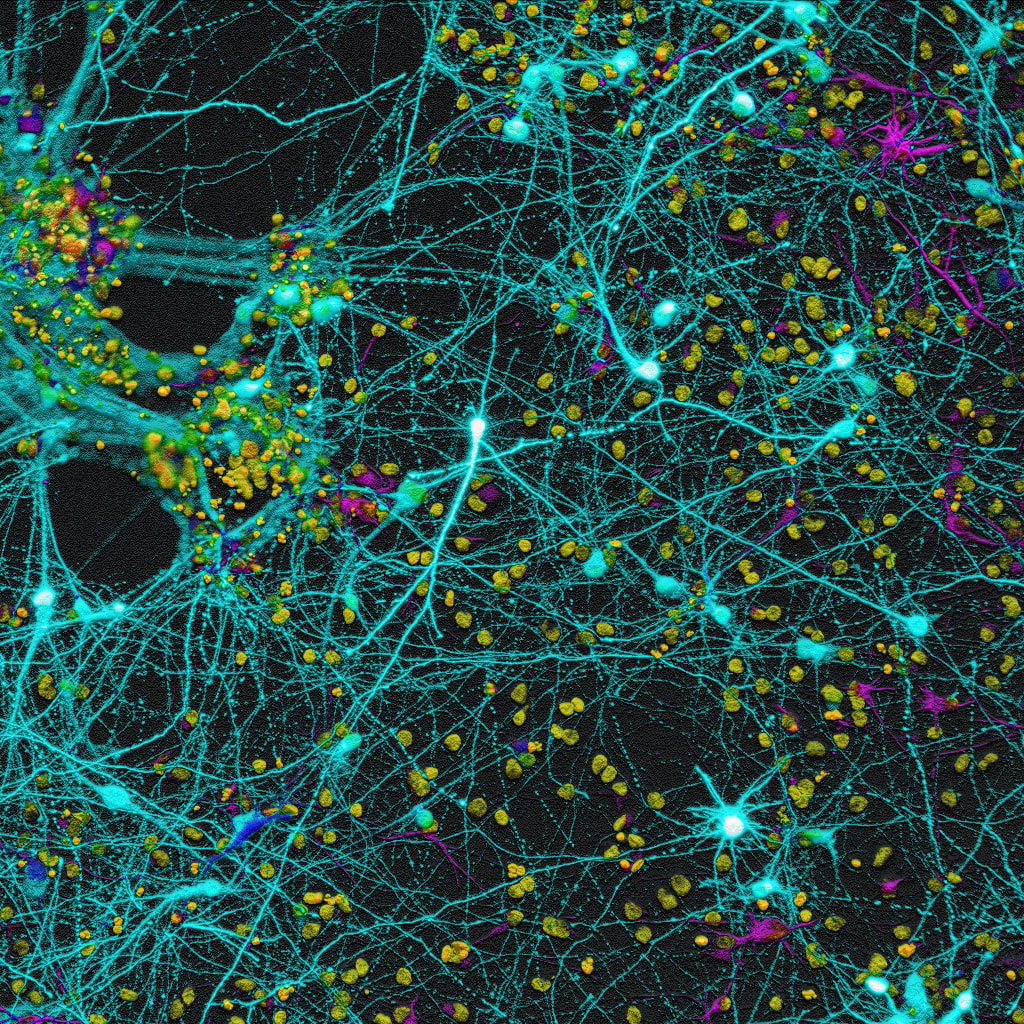

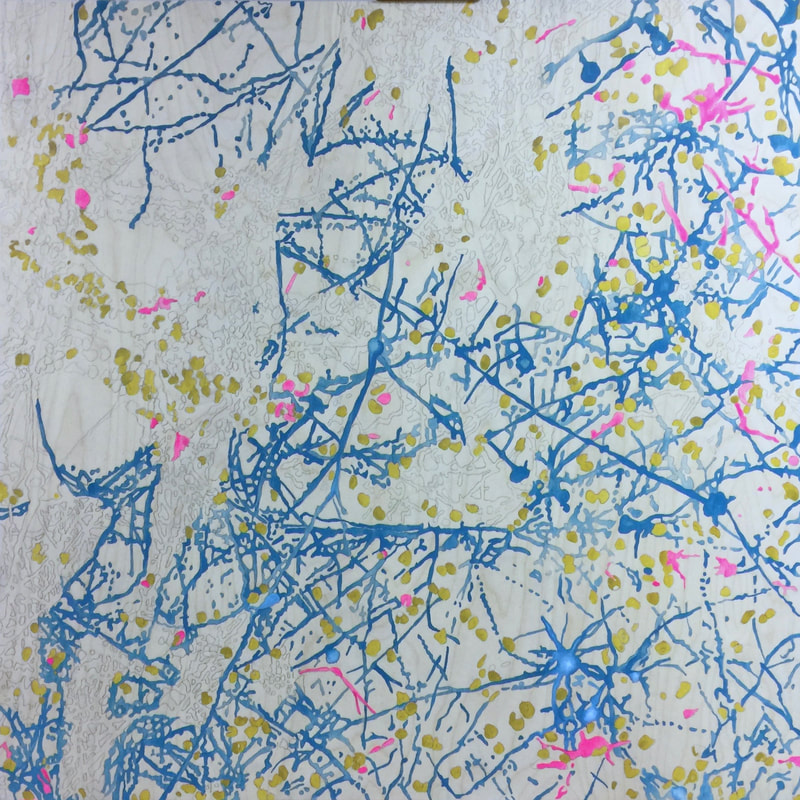

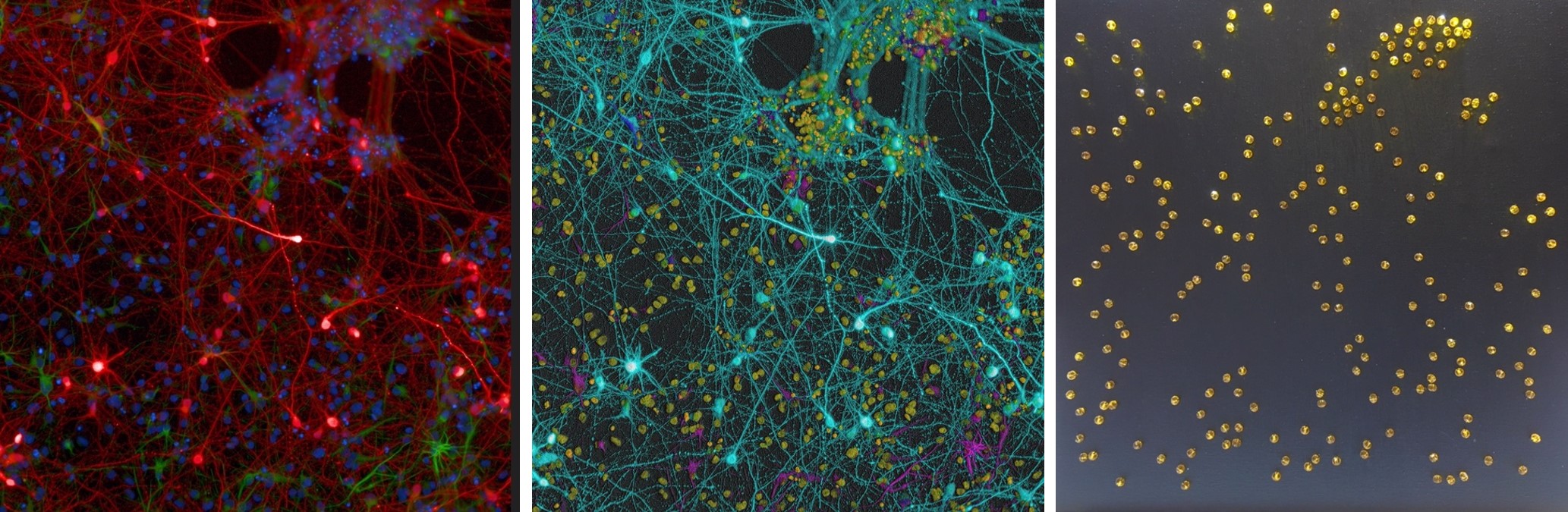

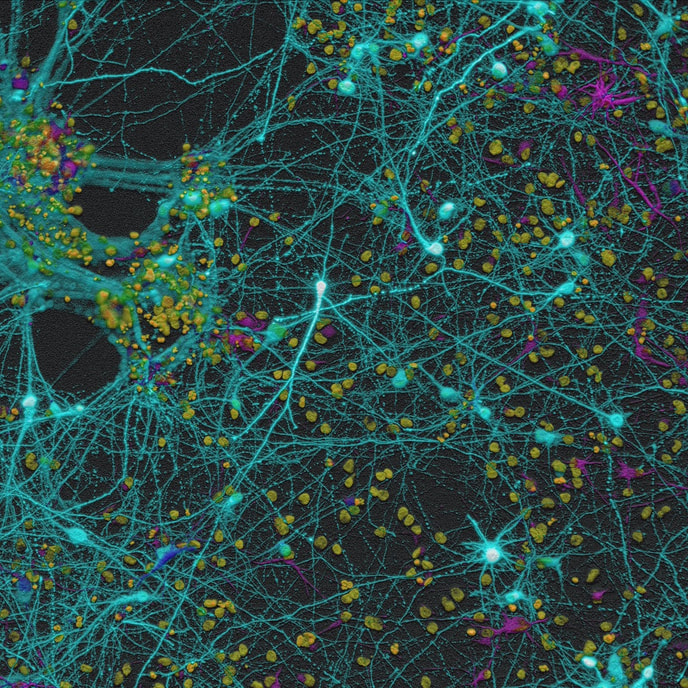

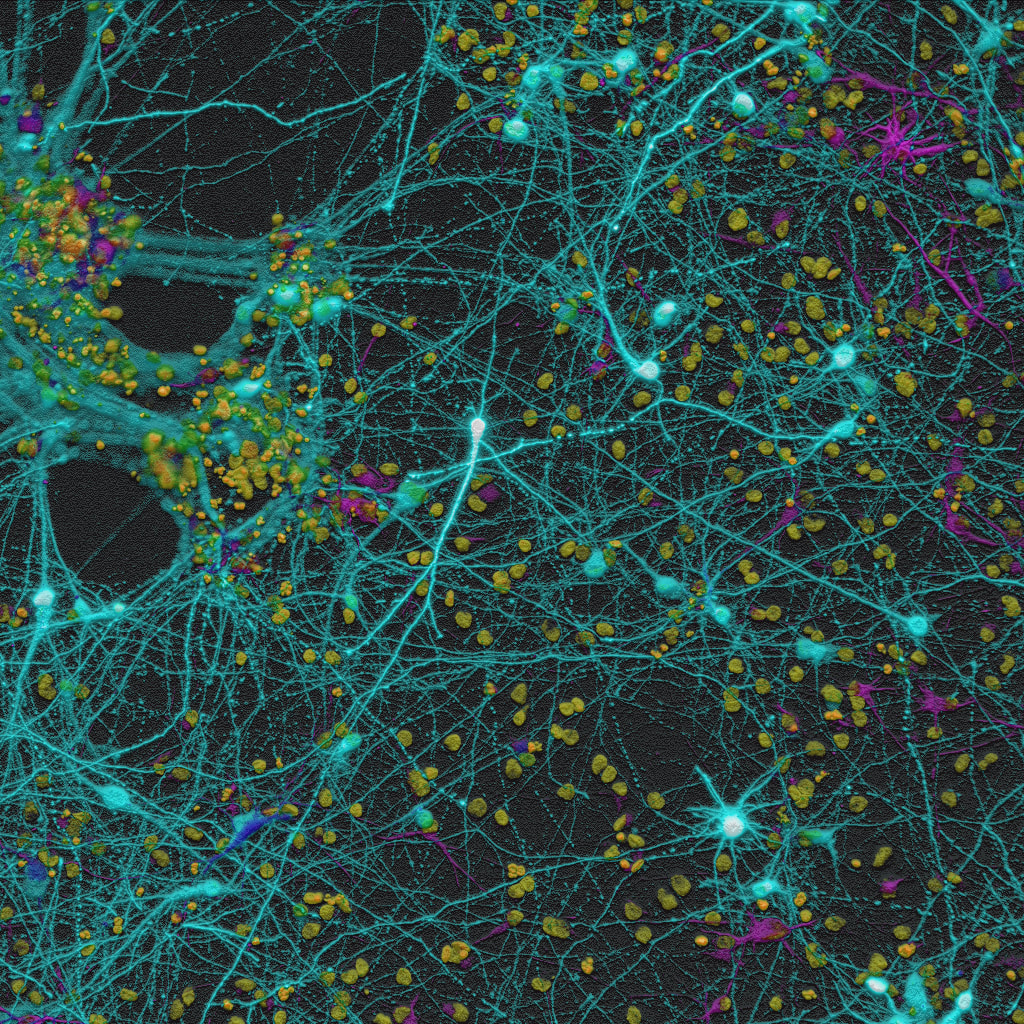

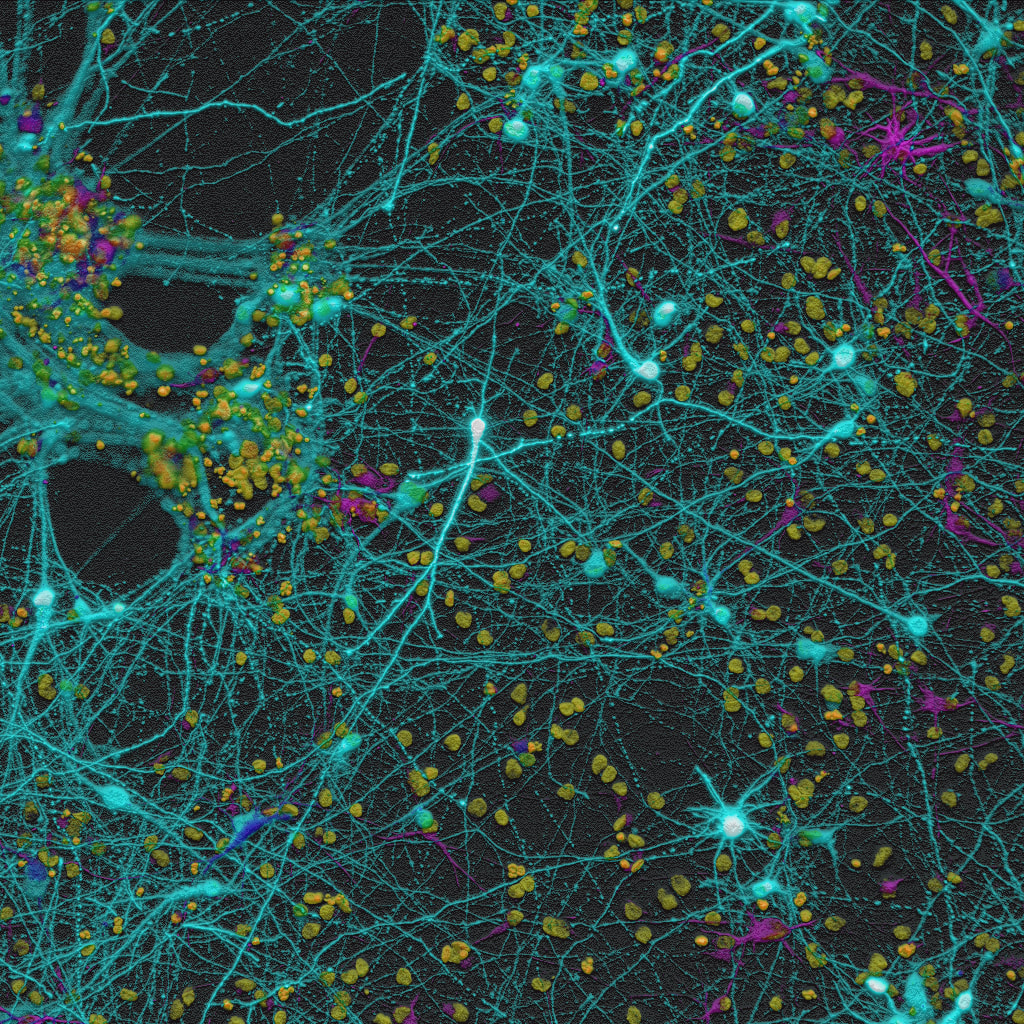

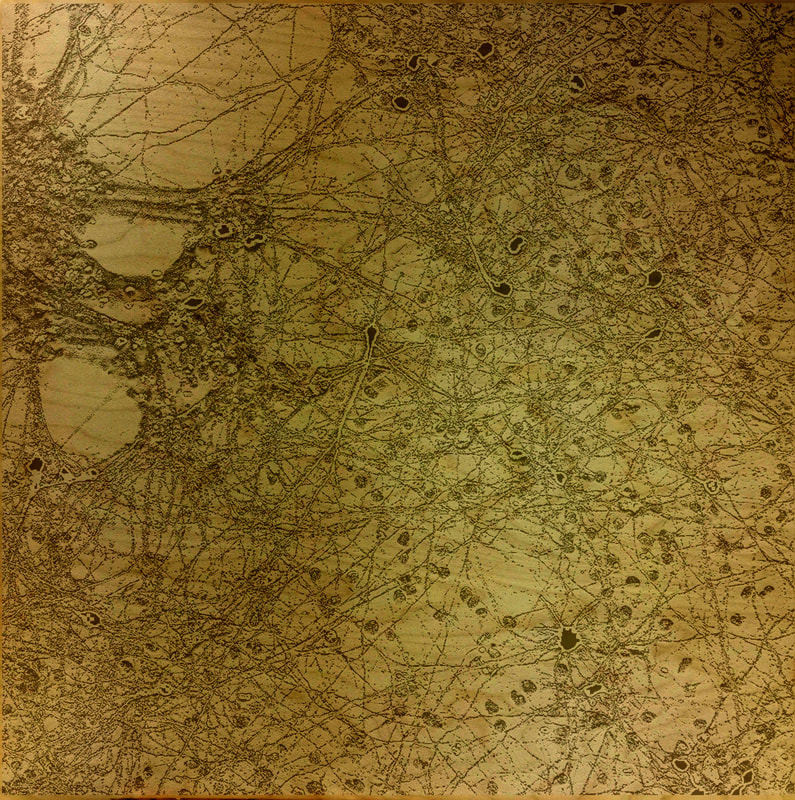

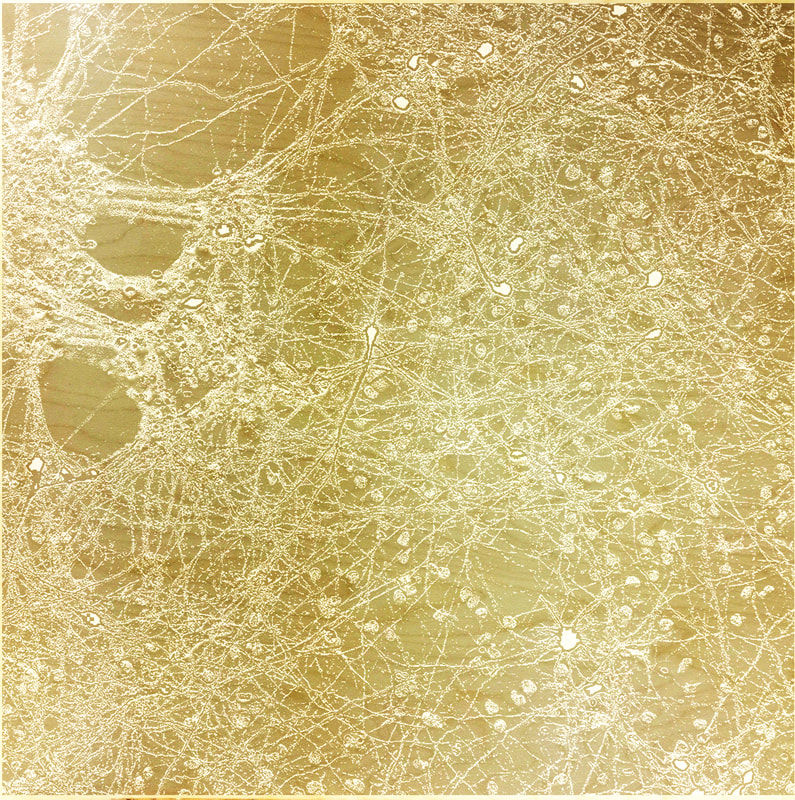

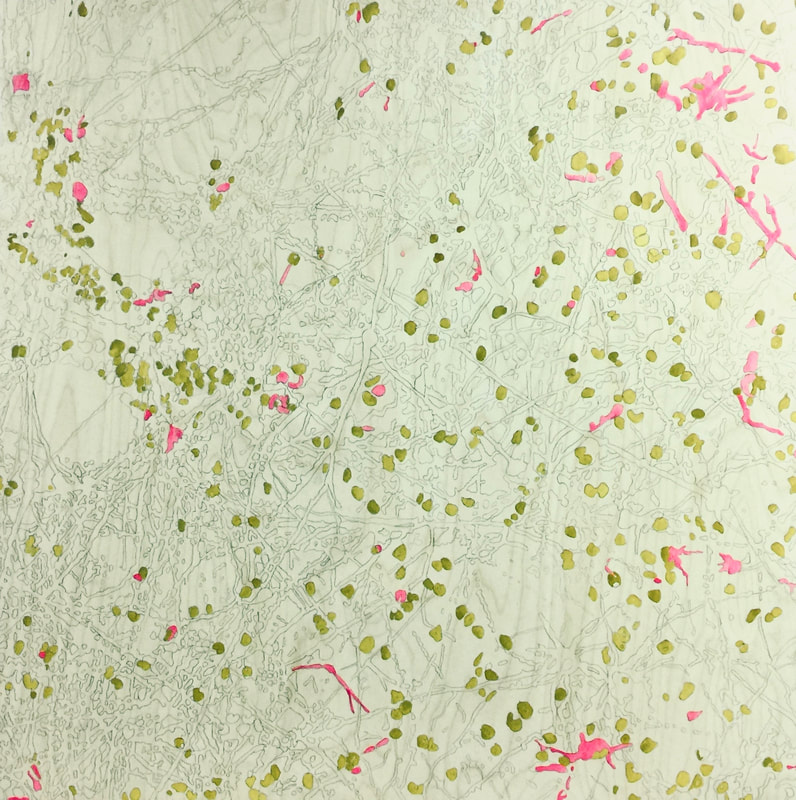

The weeks have passed quickly and my painting (Image #3) is nearly finished. My original decision to paint on wood with acrylic inks is because the wood grain has an organic pattern that interacts with the overlying image. I chose inks because they are transparent and sink into the wood in a satisfying way, acting more like a stain than opaque paint. Inks are also fragile and yet always leave their trace on the wood. Once laid down it is impossible to completely erase them. This requires careful painting and decision making throughout the process. Although I have never used fluorescent or metallic inks before, I was drawn to them for this piece because of the brightness of the digital image that Yana and I began with (Image # 1). Digitization injects light into an image, making it more luminous than it is. I wanted to somehow mirror that brightness. The interesting thing is that the fluorescent pigments will slowly lose their luminous quality as they fluoresce away their excitability to UV light. The neurons were “artificially” stained before Yana imaged the culture with an confocal microscope. (Image #1). I took this image a step further, digitally, to arrive at “Mapping Manhattan”(image #2). Using our respective art techniques, Yana and I are each bringing this scientific image into the realm of the artist. Looking at the artwork Yana and I are making brings me back to the idea of scientific models I talked about in Blog # 10 (November 16th.) In some ways, Yana’s beadwork and my painting are both abstract models of the original image. In my piece (Image#3), I was fairly careful to render it accurately yet it is still less complex than the original. Details are left unresolved, helping to emphasize the main structures. To be useful in explaining complex phenomena, a model must pare down information to its essentials. The model can then make the overarching characteristics of something, such as a network of cells, more accessible to any viewer. Another important aspect of scientific models is the ability to manipulate various dimensions. In the Week 11 Blogs of Diaa & Stephanos, Stephanos presents his mathematical model of neuronal activity in memory. Mathematical models expand our ability to visualize processes and events that our brains are not capable of holding onto in ordinary circumstances. This type of modeling is a powerful simplification because it allows us to then manipulate variables and that our conscious minds would lose track of within several mental operations. Scientific models use the same technique as artist’s images in simplifying and emphasizing specific aspects of phenomena. If all details are included in a “scene”, we get lost in the noise. Sensory processing in the brain also plays that role for us by directing our attention to the salient details around us from moment to moment and then constructing a model of that experience in our brains. The model becomes a memory which may be altered repeatedly over time in the process of being stored, retrieved and stored again. Our brains need this sorting to take place to direct our attention to the most essential aspects of an experience. Once the basic structure of a memory or knowledge about the world is formed, we can more easily embellish it with more detail. Learning through time and experience requires us to redesign or reorganize the model, often increasing its scale and complexity. But it must start simply. I have learned this from teaching. So if the model creates the structure within which new information and experiences can fit, then the role of the artist and scientist is to create a compelling, accessible and comprehensive model or image that the viewer can take away and refer to later, developing it further with their future experiences. Again, I would like to point to the Beholder’s Share. Yana Over the past several months, I have been listening to a lot of art-related podcasts. Currently, my favorite one is “Your Creative Push”. In the process of listening to interviews of multiple artists, certain elements appear again and again. These include:

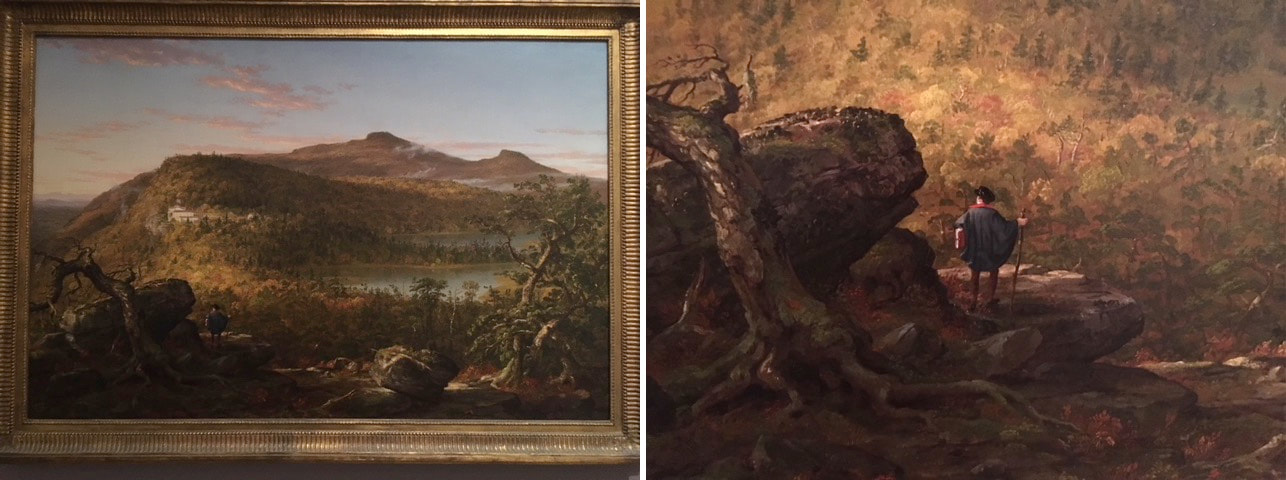

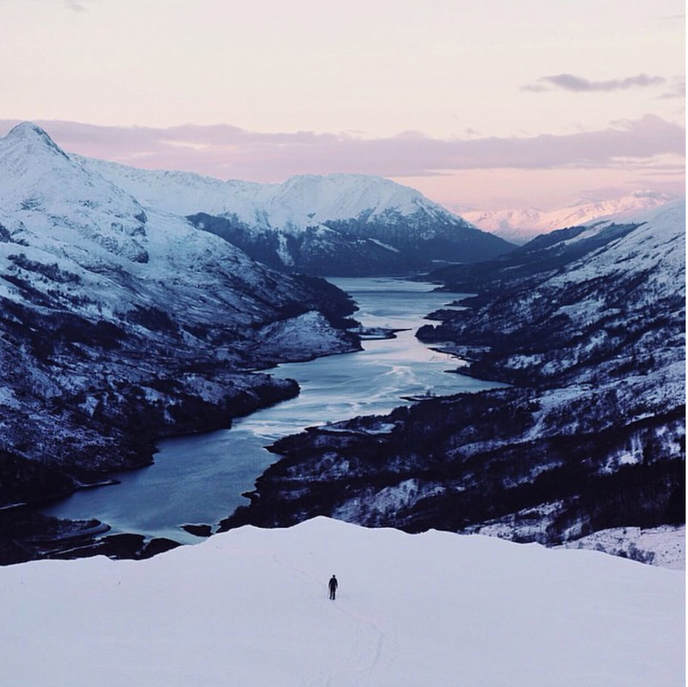

In several of her posts, Darcy wrote about the importance of “beholder’s share” in viewing art. While from a creative perspective, the concept sounds very poetic, a similar approach in science would have been called “bias” and would carry a much more negative connotation. But as much as we would like to remain objective in recording our scientific observations, we know that we are all guilty of it. When you are using data to construct a cohesive scientific model, it is akin to assembling a puzzle - you do your best to make the pieces fit together. This means that rather than trying to fit a “square peg in a round hole”, you begin your search with an assumption that you know what you are looking for to complete the missing pieces. So how does this relate to art? Do we go out into the world with the full intentions of openly observing our surroundings or are we consciously or subconsciously looking for a particular puzzle piece that is missing in our current work? I believe that the latter version is probably more prominent than we would like to admit. We perceive the world through the prism of looking for a solution for our current challenge (in both art and science). Last week I wrote about the inspiration I drew from Theordore Rousseau’s painting “The Forest in the Winter at Sunset”, which I wanted to combine with a jewel of hope. This week I happened to go to the Brooklyn Museum, where I saw the following 2 paintings. What in the world do they have to do with my work? Well, I was mesmerized by minuscule scale of a single person juxtaposed against the vastness of each of these landscapes. The same feeling came from observing the work of Richard Gaston, who photographs people as tiny speckles against the grandiose backdrop of nature. This is how I wanted to position the white jewel of hope mentioned in my previous post against the background of the intertwined neurons. Over the last several days, I was finally able to start working on the first layer of blue neurons from Darcy’s image. I am continuing the prop up all of the cells and now adding long processes to connect them to each other and eventually create a dense network. And I am just beginning to play around with the question of where the white jewel should go… Darcy If we accept that simplified models (such as my example of the cell in the last blog) make scientific knowledge more accessible, I think art also has a powerful role that is similar. Part of what art evokes is an emotional response in the viewer. Emotion motivates interest and makes an idea meaningful and without it, we have difficulty caring even if we do understand something intellectually. So, to make science more widely appreciated it must be presented in the language of enthusiasm, inspiration, and connectedness to other human concerns. These are all components of what we call “beauty”. The thing that has always drawn me to science is beauty. The elegance of an explanation or the integration of questions and observations into an awestruck moment of clarity. The sheer aesthetic burst that hits me in the chest when I look at Ernst Haeckel's radiolarians or the grief at the present acidification of our oceans, is enough to convince me that it is how I feel about nature that makes me want to explore it. Both Yana and I are working from the above image in our respective residency projects. I am slowly transforming this image into a painting. In my last blog post, I showed to progress over five weeks. The following image is my progress so far. I am understanding this image more deeply and it is becoming a sort of companion. My attention is focused on discovering the intricacies of it. A carefully crafted artwork becomes a manifestation born from an intimate connection between the image and me. I know and care about it. I have just discovered a book on this topic that I am anxious to read, Drawing as a Way of Knowing in Art and Science by Gemma Anderson. Drawing and painting are a type of close observation that requires ongoing interpretation, evaluation, and commitment. Missteps become glaring. I am learning so much about so many things while I work out the possibilities of this piece. I suppose my point is that the process of making art is personal for me and I want to convey that in some way. The viewer, however, only needs to pay attention to the beholder’s share. This emotional connection to things we study closely is essential whether it is subatomic particles, bacteria, neurons or a painting. Andrea Wulf in “The Invention of Nature” eloquently revisits Alexander Von Humboldt’s conviction that “memories and emotional responses would always form part of man’s experience and understanding of nature”. In Humboldt’s “Cosmos” he united all sources of scientific discovery of the mid-1800s with the passion of a poet. He emphasized that all knowledge should be integrated and made accessible to the general public. Scientific models embody a theory and can act as a powerful tool to further our objective understanding of nature. The arts enrich and enliven this theoretical structure, make new connections and even reorganize it. Creativity drives the questions we ask that lead to the refinement of human understanding. Emotion motivates us by giving meaning and purpose to the process of “finding out” about the natural world and ourselves in it.

Yana The original idea for my current project was inspired by a specific series of events in my life last year. To me, using the layers of neurons in this work represents certain layers of my knowledge, interests and passions, which have been temporarily covered up and moved to the back burner. Looking through my sketchbook, I came across an idea that I jotted down last November, while visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While it is not the type of art I would usually go to see, “The Forest in the Winter at Sunset” painting by Theodore Rousseau caught my attention. I remember, I sat down and contemplated over it for a long time. I was trying to find a way to translate it into my art style. While I have seen a lot of artists draw parallels between neurons and trees, I was trying to dig for something deeper. I wanted to catch the essence of being caught in a dense thicket. I took out my sketchbook and scribbled the following idea along with some notes. I was trying to figure out what to place in the center. Around the picture I had the following notes:

A bit later, the idea evolved into this, which I temporarily titled “Hope in a forest”… My current project with Darcy is deeply rooted in these ideas that were floating through my head last year. But as the project progresses, it continues to be influenced by more current events as well. That is why I am considering revisiting a couple of elements that I have used in my previous pieces. Namely, placing a clear white jewel somewhere in the depth of the network, similar to the way I did it here: I may also follow one of my original ideas and allow certain branches to reach out beyond the limits set by the canvas. But for now, I am working through creating enough cell bodies to sufficiently populate the canvas. Darcy When I look at this image it inspires so many metaphors for me. These ideas tumble over each other and intertwine in a beautiful, tangled pattern of nature... both nature out there and the nature inside me. All organic systems require connectivity. From atoms to cells to ecological webs which all connect life together into a vibrant, scintillating web of communication and interdependence. We cannot separate out one component from this complex set of relationships because one thing removed, changes both the system and changes the component. Yana’s and my artwork flows from this image and carries our unique responses. In the end, our separate pieces will reveal something of the minds that have created them and our individual interpretation of what is meaningful in the image. I am increasingly convinced that this process is rich with ideas and insight. My progress so far… Progress is slow for both Yana and me because we have both chosen deliberate and meticulous methods. This is good in the end because we can watch our work unfold with time to think about what is developing. For me, this is the point of doing the work. Ideas swirl around in my head and finally, the insights start to gell. This takes time.

I had the pleasure of spending the past weekend with my wonderful children who are steeped in science and also deeply appreciate the arts. We had lively discussions of many of the questions I am asking in this project about the close and necessary relationship between science and the arts. My stepson, Andrew Cameron (a microbiology professor), he came up with the idea of scientific models as being one of the closest connections between science and the arts. I have previously talked about the arts as being a Gestalt that originates in the right hemisphere of the brain and also the importance of this integrating part of our brain in processing, enriching and storing knowledge. Andrew’s idea is an elegant demonstration of this. A scientific model often takes highly complex and abstract ideas and builds a framework that makes those ideas more accessible because it favors simplicity. An example of this is the cell. The model may simplify the structure and function of the cell makes it more approachable to everyone. A grade 9 science student who has very little previous knowledge of a eukaryotic cell would process the model very differently from a geneticist, a physiologist or a virologist, who would, in turn, bring different emphasis to their viewing. In a scientific model, all the pieces must fit, relate and interact and are less meaningful if reduced to their parts. A scientific model is a testable framework that contains the overall understanding in a particular scientific theory but also acts as a beacon for moving the research forward. A scientist can then go about designing new research, fitting in new information and even predicting what will eventually be discovered to flesh out the model (eg: the Higgs boson in particle physics). Assuming that an artwork is a representation of the artist's abstract and complex experience, it may be a framework similar to scientific models. A work of art contains interrelated and interdependent content for the viewer to grapple with. But art, like scientific models, also exposes holes, such as ambivalence, that allows the viewer to flesh out the artwork and extract personal and universal meaning. This relates to my previous discussion of the beholder’s share developed by Rigel, Gombrich, and Kriss. Great art must leave room in its overall “structure” for the viewer to gain unique insights and in some way light the path forward to new art and ideas. I will carry on with these ideas next week and discuss the organic and dynamic nature of scientific models and art. Yana Last week, Darcy, Kate and I had a very productive Skype call, where I expressed my concern about the technical challenges of attaching the beaded cells to the canvas in a way to would make them stand. Kate suggested using acrylic rods. It was a good start, but honestly, I was not thrilled with the idea. I felt that the width of the rods, despite being hidden behind cells, would take away from the delicate nature of the image. But it got me thinking… The next day, I went back to the bead store and found long, thin black beads. I created the cells with a long and sturdy wire stem in the back. The stem was threaded through the black beads and then the wire was pierced through the canvas. But now what?... I was really tempted to stick small pieces of Styrofoam to the back ends of the wires, but again, that would prevent me from doing any further sewing. So for the time being, I just put small blobs of modeling clay onto the tips to keep them from falling. Now imagine doing that several times, flipping the canvas back and forth and hoping that nothing would fall out. Slowly, I was able to create and attach nine purple cells. As with the yellow beads in the background, I need to find a compromise with myself on which cells to include and which to leave out. I was particularly concerned about the relatively uneven distribution of the purple cells across the image giving a sense of imbalance. This is where I’ve hit a wall. The process of creating each cell was so slow and intricate that I decided to take a break from the actual artwork and think about the logistics of creating the next layer - the light blue cells. When I bought the black cylindrical beads, I got them in 2 lengths with about a 1.5-fold difference.

Darcy

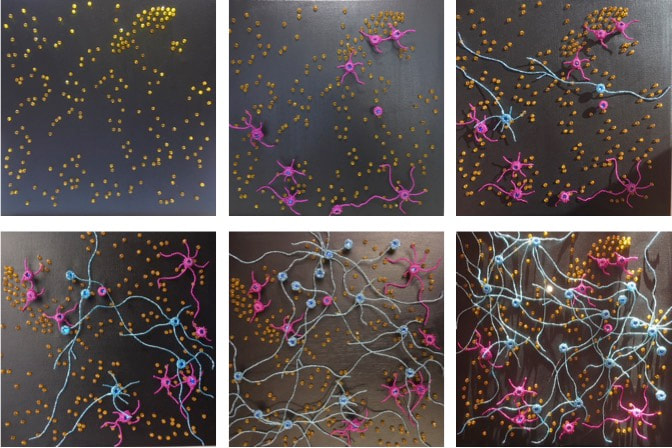

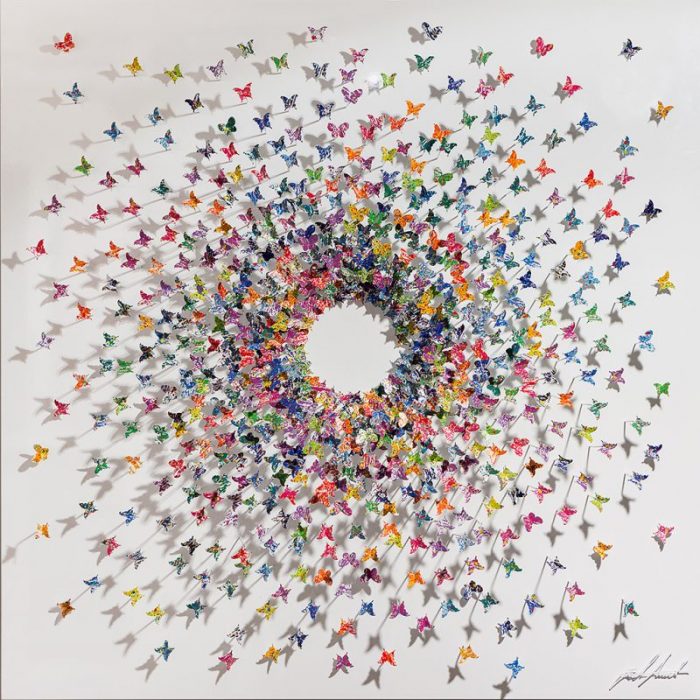

I suppose my interest SciArt is not only to investigate the ways in which the arts and sciences work together but also to argue that they are critically important to each other and in a sense inseparable. One of the ways I study this intersection is through my own artwork and so will continually return to this theme. During the Age of Enlightenment, as rationalism and empiricism vied for dominance in the scientific approach to knowledge, they both moved science further and further from the arts. This separation has persisted until fairly recently. One of the most important scientists of the Age of the Enlightenment, Alexander Von Humboldt (1769-1859) did not have the attitude that our emotionally dominated intuition should remain out of the picture when trying to decipher the complexity of nature. A close friend of the polymath, Goethe and the philosopher Schelling, Humboldt saw nature as an integrated whole where all organisms and processes are interdependent. According to Andrea Wulf in The Invention of Nature , Humboldt tirelessly explored, measured and wrote about the natural world he experienced through his global travels. His copious writings always contained both close scientific observations of nature and powerful poetic prose. Humboldt allowed his emotions and sense of the connectedness of all things to create a highly accurate and compelling vision of the whole of nature and the way it interconnected. He was even able to show how economies, politics and human-induced climate change are all shaped by the characteristics of the natural world. But most importantly, Humboldt was the first rigorous scientist to point out that humanity is as dependent as any species on a richly diverse planet. The difficulty humanity has in viewing nature in this highly interconnected way is partly because of the way our brains organize our experiences. The human mind seems to use opposites as a way of understanding the world. These can be as simple as bad vs good or as sophisticated as romanticism vs rationality. It is more a mental tactic than a realistic view of the world and grossly oversimplifies the way nature functions. This dichotomizing of concepts, unfortunately, leads to a “this or that”, “us or them” worldview that is misleading because nature (including humanity) is more an integrated and interdependent whole in which opposites are on a continuum and its components are more alike than they are different. It takes hard mental work to avoid these biases. This is exactly why we need the rigors of science to give us a less prejudiced view of nature. Yet science is more powerful and insightful if working with the great integrator … the arts. So it seems more important than ever that the arts and sciences reunite to create a more complex and less biased view of ourselves and nature. The arts also allow us to be more comfortable with ambivalence and there is more than enough of that to go around! Here is this week’s progress on my the interpretation of “Mapping Manhattan”... I think of Humboldt as I work slowly (and a bit painfully) towards a more resolved image. Excited to see what Yana is coming up with her equally meticulous rendering of this image. Yana Last weekend, I mostly finished sewing the first layer of yellow rondelle beads. In the original microscopy image, the cell nuclei were colored bright blue, due to being labeled with Hoechst stain, which labels DNA. In Darcy’s version of the image, she switched this color to pale yellow, which makes them look more delicate and maybe a bit sad. The vast majority of the nuclei do not show cell staining around them (light blue in Darcy’s version), suggesting that they are most likely the remnants of dead cells. This after thought makes me feel like the pale yellow color is even more fitting. After creating this “lawn” of atrophied cells, I began to think about how I would like to depict that ones that have survived. First of all, I wanted the living cells to be raised above the surface, similar to the butterflies in Joel Amit’s work I posted two weeks ago. This is where I faced a major challenge. I intended to use medium sized beads for cell bodies, cover them with a pattern of small seed beads and follow Sally Curcio’s method of elevating these structures on pins (see the post form two weeks ago). Developing this technique required me to delve into the T and E parts of STEAM: Technology and Engineering, as well as some level of Math. I ended up spending the whole week performing what I jokingly called “pilot experiments”, which might be referred to as studies in art or prototypes in engineering. None of the methods suited what I was trying to portray. On Saturday, Darcy, Kate and I had our next Skype call, where I received some helpful suggestions on how to attach fully elevated structures to a canvas. The very next day, I rushed off to the bead store with an idea of my own that merged their suggestions with some elements I was thinking about before. The materials I was initially looking to get turned out to cost an arm and leg, so I had to compromise and change my plan again. The set of pictures below shows the series of “experiments” I performed to determine the optimal method for creating the cell bodies, before arriving at my final version, which is shown on the white background on the bottom. The background has a stain, because I used my daughter’s old canvas to try to prop it up before risking damaging my own. It took me a long time to decide on whether I should stay true to the colors on Darcy’s image, or if I can put some bright blue Hoechst stain back in. Quite honestly, I ended up doing it primarily due to being unable to find the right shape stones in colors that would match. But I guess this color can serve as an additional factor that distinguishes the living cells. As you may have guessed, the large photo on the right shows how the whole cell came out. This is a first of many. This week I am on to the next challenge: if propping these structures up requires me to stick wires through the canvas into a supportive layer of Styrofoam that I will attach in the back, how do I do that without losing my ability to keep sewing other elements onto the canvas?.... Darcy "Navigating" I have started painting the drawing of the projected image I talked about in last week’s blog. The digitally rendered microscopy image I am working from, “Mapping Manhattan”, is very complex and so the initial drawing is like an imperfect maze. I’m not trying to replicate Yana’s original microscopy image but instead I am just watching how it evolves through the stages I have imagined. The painting process demands that I pay close attention to the original image because progress is slow. I, therefore, have a lot of time to think about what I am doing.  “Remapping Manhattan Day 1” Acrylic ink on wood panel, Darcy Johnson “Remapping Manhattan Day 1” Acrylic ink on wood panel, Darcy Johnson I started with the magenta because it has a distinct pattern and there is less of it than the other colors. I used the magenta structures to orient myself to the whole space and then added the yellow cell bodies. My drawing is such a mass of tiny lines that I have to hunt for every structure. It felt like I was stargazing. I had to find a clear recognizable constellation of structures and work outward from that, painstakingly filling in more and more detail. My drawing will relate to the original electron microscopy image that Yana made but at this point, I am most interested in the degree to which that happens. At this point, it is emerging as a map which reflects perfectly my sense of trying to navigate its structure. This process interesting because it allows me to not only get to know the image better but to observe myself observing the process. I thought about scientific observation mainly. This is because every time we take a data set and translate or distill it, we lose something or at the very least, change something. It is the natural evolution of the information processed by our creative brains that defines the final character of what we call knowledge of the “natural” world. While painting, I could see myself constantly interpreting the image, making choices about what to emphasize and what to forget about. At times, I felt like I was blatantly fudging the data. So, after a number of hours spent “dissecting” my drawing, I was more convinced that the role of scientific observation is to preserve the original data as well as possible because otherwise our creative brains will shape and change it without our conscious awareness. If we are creatively structuring of our reality with only oblique reference to the already filtered data of our senses, we need the rigors of science to keep us in check. Science puts together a solid scaffold we can then jump off of in the search for creative ideas that often must lie outside of scientific methodologies, in scientific theory, new experimental approaches and the arts which can inform all of these.

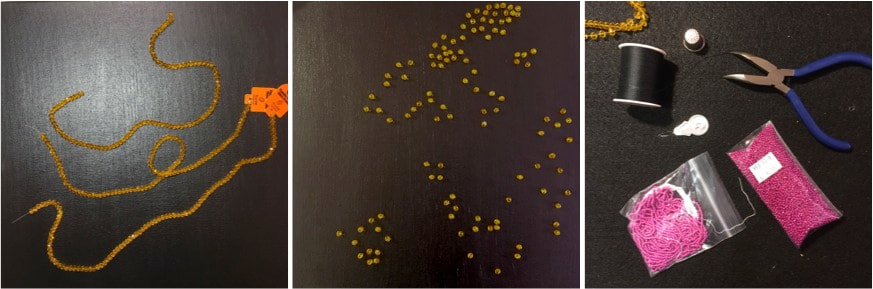

Yana After settling on creating “Mapping Manhattan”, this week I finally got a chance to go out and buy some supplies, including a canvas and beads. I painted the canvas with black paint (though it ended up looking a bit like wood in the photo) to create the background that is typical for fluorescence microscopy images. When shopping for beads, I had an internal debate on whether I should stay true to my method of using small seed beads for recreating all “pixels” in the image; or if I should choose the bead type based on the shapes present in the actual image. I ended up choosing so called “rondelle” beads, which have multiple faces, to recreate the yellow nuclei scattered across the image. I also purchased bright purple beads for the occasional cells that Darcy pseudo-colored this way in the image. Unfortunately, the light blue beads that are required for the majority of the cells in the image were backordered. I began by studying the image (which we later discussed with Darcy as an important step in creating art) and soon realized that there were too many yellow nuclei for me to feasibly fit on the canvas. This made me think of a conversation I had with another artist earlier this year. After looking at my works “Tortured” and “All Wrapped Up”, he asked me about how I decide which parts of a microscopy image to include and which to leave out. At the time, my gut instinct was to say that I include everything. However, this is not always feasible. Coincidentally, I began to work “Mapping Manhattan” project soon after attending the “Infinite Potentials” exhibit organized by the SciArt Center. There, I spoke with several artists, who described an element of entropy that goes into creating their work, presumably mimicking the partially random chains of events that occur in nature. Similar to what I have heard before, they spoke about allowing the artwork to lead the artist, rather than the other way around. My scientific mindset struggled to understand. Yet, when I looked at the almost insurmountable amount of elements in Darcy’s image and thought of the question about leaving out certain elements, I decided to compromise. Therefore, I chose certain geometrical combinations of nuclei, which I called “motifs”, and used them as guidelines for creating a semi-random distribution of rondelle beads representing the nuclei. While trying to stay true to the overall composition, I realized that they ended up taking slightly different positions relative to each other than in the original image, but I guess that is OK. In contrast to some of my previous works, I am looking forward to working with one color at a time, layering and developing the piece over time in all 3 dimensions. Darcy What the work shows us. So, here I am again. After a week of percolating, I started my painting. One approach to image development I have used over the years is projection and redrawing. I usually work from a spontaneous abstract sketch and project it onto a much larger paper or wood panel. I redraw or paint it using a number of different approaches. I am able to study the evolution of the image as it changes in scale and media. For more on this process, visit my website darcyelisejohnson.com I have long been fascinated by the content and purpose of an image whether for science or art. What does it teach us? What information does it distill? Why is it compelling to look at? Drawing and painting are one of the ways I can study an image and gain insights into its many interpretations and incarnations. Yana and I had a long Skype conversation this morning. We discussed a re-occurring topic... What is art for? Can artistic and scientific imagery inform each other? What does this say about what we are each working on artistically in this residency collaboration? Questions, questions, questions… the driving force behind both art and science. So in response to all of these questions sometimes I need to stop thinking and just work …. to observe and understand what I am doing. Here was my experience yesterday as I began the painting… First, I projected the image Yana and I have decided to work on in our own ways. Then, I projected this digital image onto a prepared wooden panel and redrew to. Here is the finished drawing, that is waiting in my studio for the first layer of acrylic inks. So, I now have a better understanding of my purpose and direction in this project. It has come from the metacognition we all use, all the time...observing ourselves observing the world. As I was drawing, I became familiar with the image in a deeper way. I gathered details and interconnections. How is my interpretation of this image related to others I have drawn in the past? What details am I focusing on? What type of emotional response do I have to the image and why? What do I choose to leave out, because when we process an image mentally, we must leave things out, we must make choices and it is the choices we make that become the most interesting aspect of the finished work. Again, questions are the most important part of the process. Answer one and another pops up. How might this type of observation apply to science? If scientists make observations of natural phenomena in a particular situation then another scientist must be able to reconstruct this “experiment” and observe the same thing. Seems simple enough but it is incredibly difficult to individually understand the limits of objectivity in the human brain. I’m not suggesting we can't do this, in fact, I’m really saying that we need the rigor of science to codify nature in any predictable way because, without this structure, it is all art.

Yana Darcy and I have decided to move forward with the image she called “Mapping Manhattan.” From the beginning of our collaboration, I told Darcy that I would like to create something that would represent the synthesis of the field of neuroscience and the context of New York. Initially, I sent her a sketch that I made a couple months before beginning this residency. As before, it was only meant to help me get an idea down on paper, not necessarily being representative of the end product. I wanted to use it as an opportunity to merge several elements that I recently came across. I will give some examples below. In the beginning of this summer, I took my daughter to the Children’s Museum of the Arts in New York City. Going in, I expected to spend some time with her, guiding her through some simple drawing or sculpting hands-on activities that the museum provides for the kids. I was in for a big surprise. In one of the rooms, I saw the work of Sally Curcio and was completely blown away. Under a large glass bubble, there was a bright reconstruction of the Central Park Reservoir made out of beads. Next to it, another bubble showed a depiction of Miami Beach, also out of beads. And then there was a large fictional landscape. I remember thinking that it has been a really long time since I last felt so mesmerized and excited about something. I was hooked on this beadwork. In August, my family went on vacation to California and while walking through Chinatown in San Francisco, I stumbled upon a gallery featuring works by Joel Amit. Most of his works were mosaics made of miniature butterflies, birds or fish. These elements were handcrafted to be similar in shape, yet all of them were uniquely different. They were protruding to various heights from the surface, creating 3-dimensional images that could be related or completely different from the individual components. On the way home, I was deep in thought about how I could incorporate something similar in my work. Given Darcy’s creation of “Mapping Manhattan,” I am currently playing around with how I could merge these elements and marry them to my medium of beadwork. Darcy Time to Focus Yana and my discussions and posts are focusing on a collaborative artwork stemming from Mapping Manhattan (below). As I talked about in the last post, this is Yana’s confocal microscopy image of neurons that was not useful for science but became a playground for artistic ideas for both of us. I now need to come up with my next step in our collaboration. The problem is that I have so many ideas and possible approaches that I feel myself shutting down. This is a universal difficulty with creativity. How to home in on the exact approach and media for an artwork, to the exclusion of others. Because I’m a hoarder of ideas and possibilities in art, it is even more difficult. Here are the questions I am absorbed by right now: Are there more insights and expressions available in this image for me? It will require a certain amount of deconstruction so that some space is created to reenter the work. I didn't realize it would be this problematic. I want to have some idea of both the steps and the outcome so I can relax into the work. Otherwise, the process is aimless and goes down a blind alley very quickly.

So, as artists and scientists how do we decide or choose the specific method to answer a question? Well, I suppose we first need to refine the question. What am I trying to communicate? What problem am I trying to solve? What insight am I trying to uncover? Can I answer these questions in a conscious rational way or do I need to allow my subconscious mind to hit on a solution? Either way, I’m stuck. I enjoy the image the way it is. Is there any room to move beyond what it is now? Is that what we mean by “finished”... no more possibilities... complete and self-contained? It’s like a small death. I turn to the section of Lenard Shlain’s, Leonardo's Brain on creativity and insight. The right hemisphere goes on processing long after our conscious, logical left hemisphere has moved on to more immediate pressures. According to current neuroscience, this explains the sudden flash of insight that happens after we stop thinking about a problem consciously and rationally. The solution bubbles up later into consciousness sometime while our left hemisphere is otherwise occupied. The theory is that there are times we need to shut off the language and linear processing such a logical evaluation in our dominant left hemisphere to let the right hemisphere to come up with more creative solutions. So, I went to my studio today to prepare a large wooden cradle for something… not sure what yet. Then I came back to my computer and played with Mapping Manhattan layered on the wood surface in Photoshop. Here are some results. Waiting for insight…. |