|

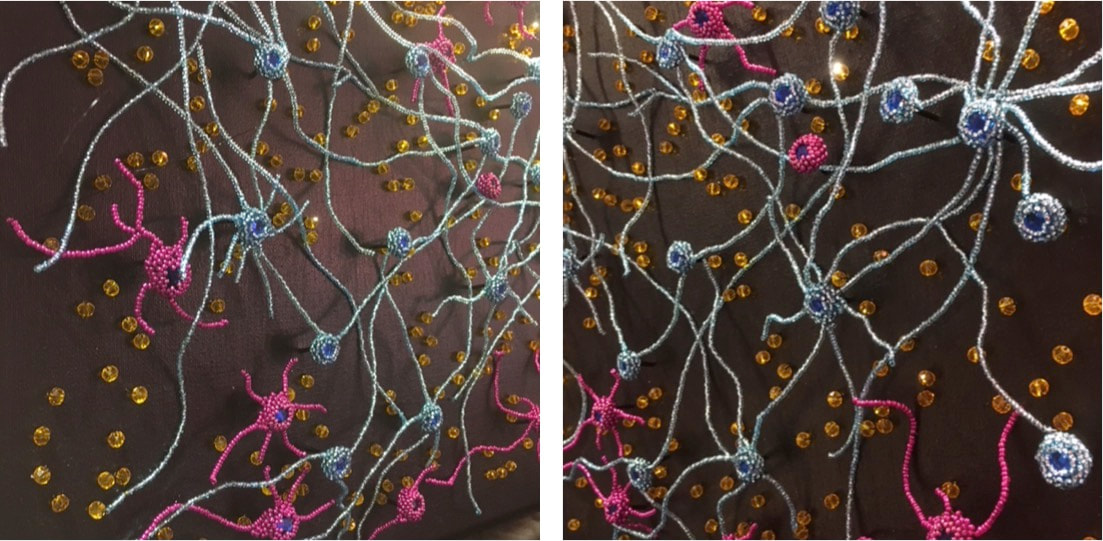

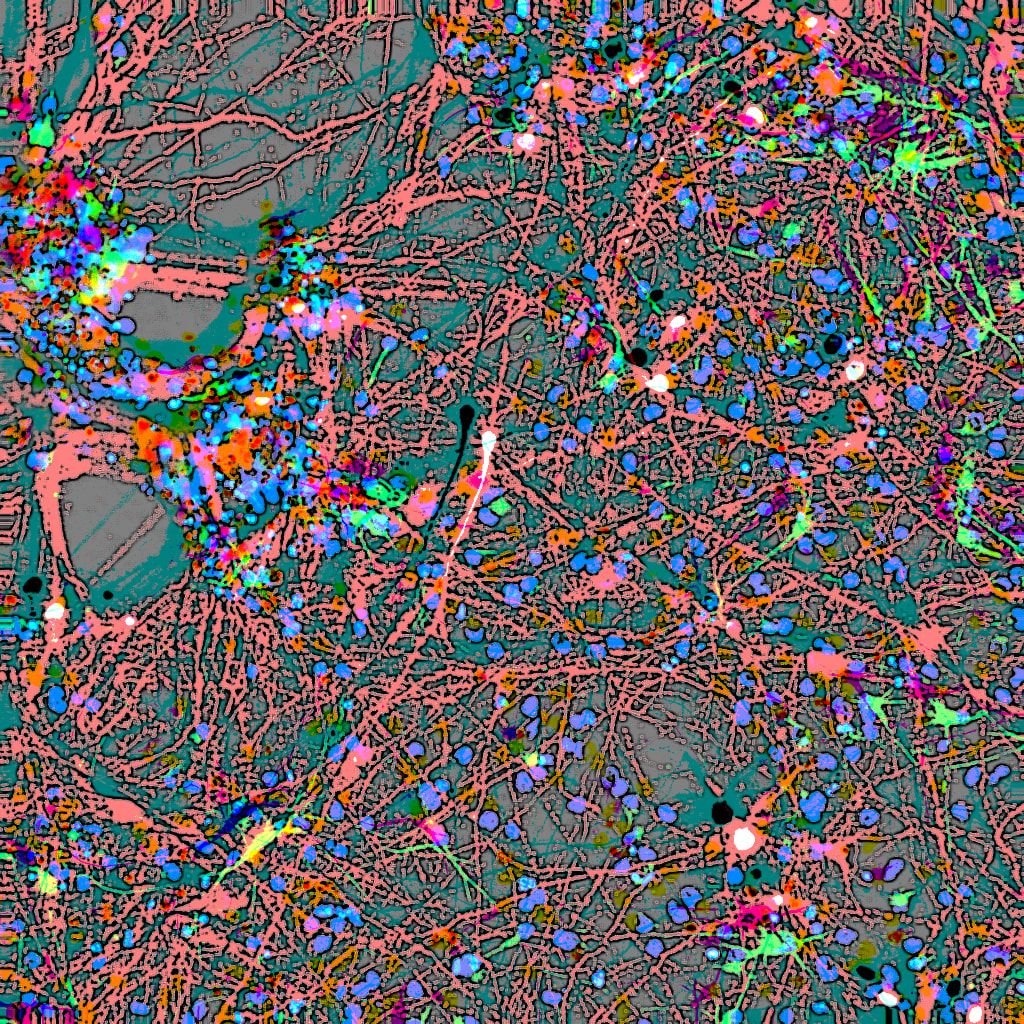

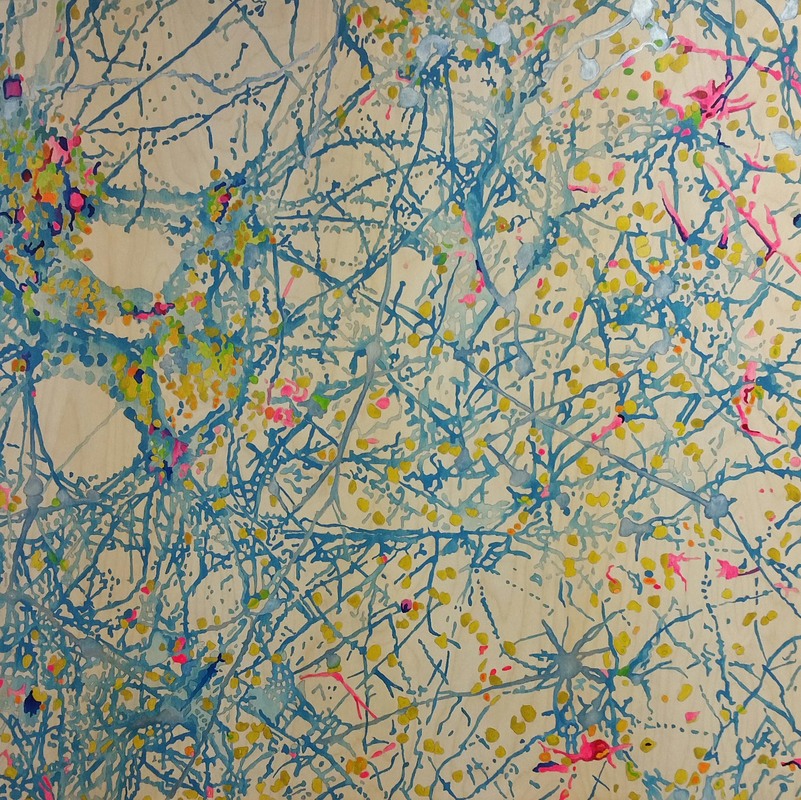

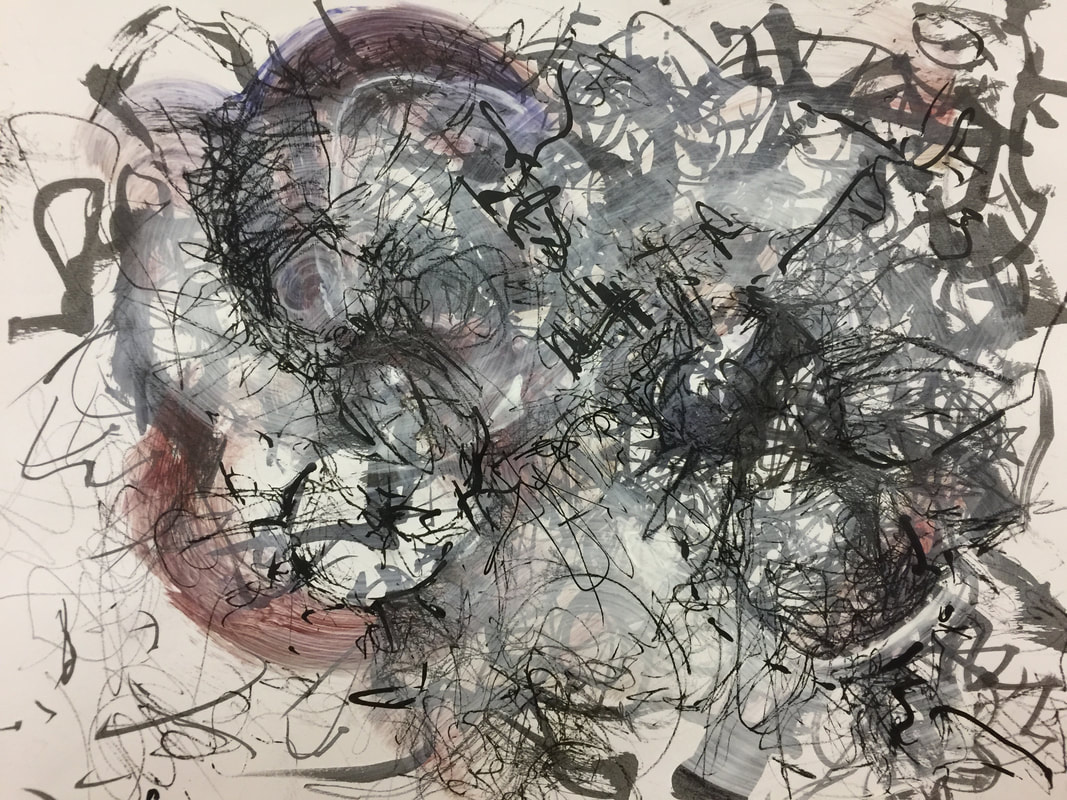

Yana Continuing in the theme of balancing the structured scientific method and free play (as Darcy writes about this week), I keep struggling with letting go. I strive for scientific accuracy, yet sometimes you need to decide what to keep and what to leave out to gain clarity. Sticking to the original image makes me feel in control, while venturing off with making my own imaginary connections (which are totally possible in this context) feels like throwing in the towel. And then balancing all of this with the concept of composition and making the image visually pleasing… Letting go is difficult… In science, “bias” is a dirty word. The same goes for Photoshop. Altering data and being selective in what you pay attention to leads to direct risk for being very subjective and failing to see the real picture. You can get carried away with trying to fit everything you observe into a picture that you have already formed in your mind. It is quite dangerous. Darcy previously wrote about creating models from of observations. While it may be important for understanding difficult concepts, you cannot grow too attached to your model. Unfortunately, there is also a factor of consistency. A scientist may keep publishing papers proposing a certain model of a disease or natural phenomenon. And then suddenly they come across a piece of evidence that contradicts their initial thinking. What do you do in such a situation? Well, if you publish the new data as it is, you will be accused of being inconsistent, which will make people question all of your research. Who would want to do that to themselves? So people try to find a way to slightly alter their models to accommodate for new evidence. But is that the right way of going about it? When I was in graduate school, my advisor used to jokingly say that bias is a sign of knowledge. That it allows you to use your experience to observe what otherwise may not be obvious. While it may be true that a trained eye will see what others would not, the “beholder’s share” needs to be consciously controlled. So where does this lead us and how is it relevant to art? How do we gain clarity and not leave out important details? Who is best and judging what is important and how will you know if something important is missing? Darcy So here we are in the last week of the residency. I am ready to start a new painting and plan to explore “Where’s the Party?”. This is another collaborative image of Yana’s and mine. This will be the sister painting to “Mapping Manhattan Revisited”, done in a similar way in order to observe the differences in process and outcome. I will start by projecting the image on a 36” X 36” wooden cradle, redrawing the image in graphite, then painting directly onto the wood with an array of bright inks in order to recreate the pattern. I will continue posting the results of this project and others on my personal blog, darcyelisejohnson.com. I have come to enjoy painting when there is a procedure to follow even though I will always produce some artwork that is spontaneous, expressive and unpredictable. It is wonderful to lose myself in an abstract image but there are times when this process of making art ends up in a mess of chaotic ideas. Even so, the mess yields its own wisdom and provides a pathway forward. (See Image #3) A structured method pushes my creativity in a different way than the more intuitive paintings and drawings. It provides a framework that holds me in and anchors me to the image. I am able to compare the results of a particular process over a number of artworks and gain valuable insights. I can play inside the boundaries I have set up for myself when I use a planned, stepwise method and discover the consistencies and anomalies in the results.

I have often thought that part of my attraction to science is the structure it provides for new and more complex insights. Scientific thinking gives us a roadmap within which our imagination can act. It is a bit like fleshing out a storyline. The important revelations are in the details. Scientific methodology keeps us focused, organized and withholds judgment until the results are in. Then we bring our intellect and creativity to the results which at the very least, point towards the next step. There is another aspect of scientific thinking that I deeply value in my work as an artist. I glean ideas from the rich world of nature and try to understand them through art. I am doing art to study and understand both myself and the world and a rational method keeps me from spinning off the edge of the world in a flurry of colour and emotion. My two halves are always informing each other, the artist saying come on let’s play in the beautiful world and the scientist saying, well, let’s make this playfulness lead us to a richer place because we are bigger and stronger together.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |