|

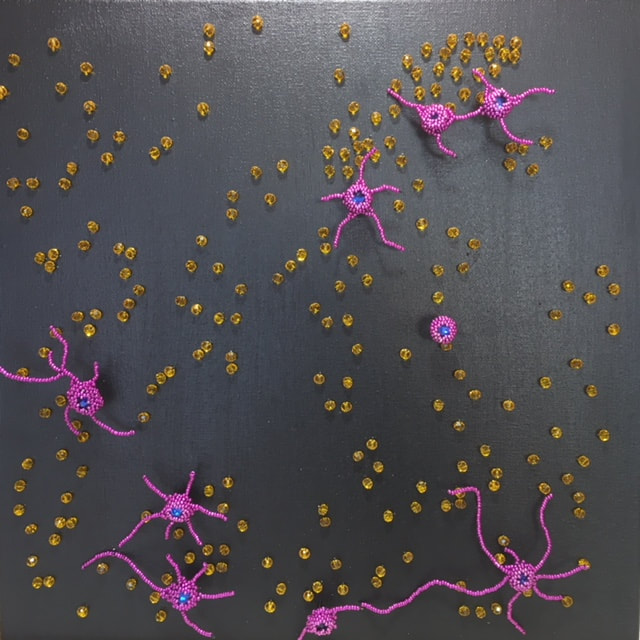

Yana Last week, Darcy, Kate and I had a very productive Skype call, where I expressed my concern about the technical challenges of attaching the beaded cells to the canvas in a way to would make them stand. Kate suggested using acrylic rods. It was a good start, but honestly, I was not thrilled with the idea. I felt that the width of the rods, despite being hidden behind cells, would take away from the delicate nature of the image. But it got me thinking… The next day, I went back to the bead store and found long, thin black beads. I created the cells with a long and sturdy wire stem in the back. The stem was threaded through the black beads and then the wire was pierced through the canvas. But now what?... I was really tempted to stick small pieces of Styrofoam to the back ends of the wires, but again, that would prevent me from doing any further sewing. So for the time being, I just put small blobs of modeling clay onto the tips to keep them from falling. Now imagine doing that several times, flipping the canvas back and forth and hoping that nothing would fall out. Slowly, I was able to create and attach nine purple cells. As with the yellow beads in the background, I need to find a compromise with myself on which cells to include and which to leave out. I was particularly concerned about the relatively uneven distribution of the purple cells across the image giving a sense of imbalance. This is where I’ve hit a wall. The process of creating each cell was so slow and intricate that I decided to take a break from the actual artwork and think about the logistics of creating the next layer - the light blue cells. When I bought the black cylindrical beads, I got them in 2 lengths with about a 1.5-fold difference.

Darcy

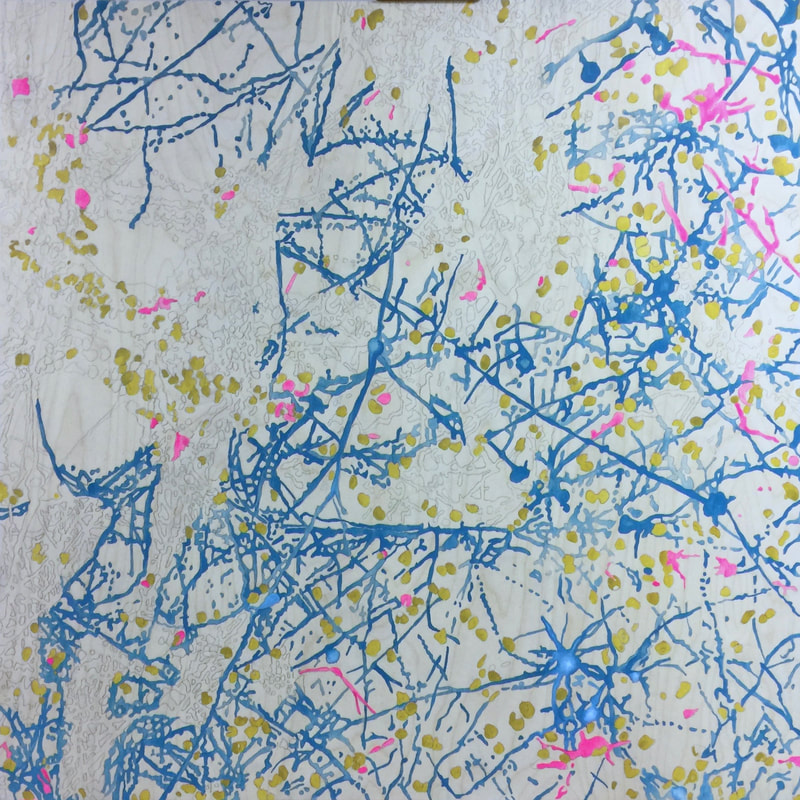

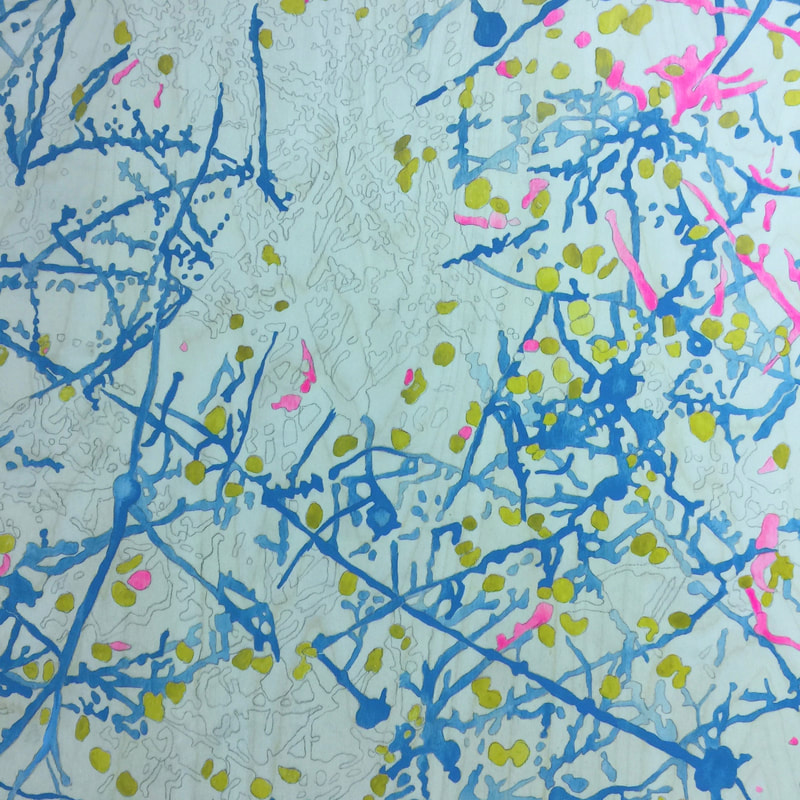

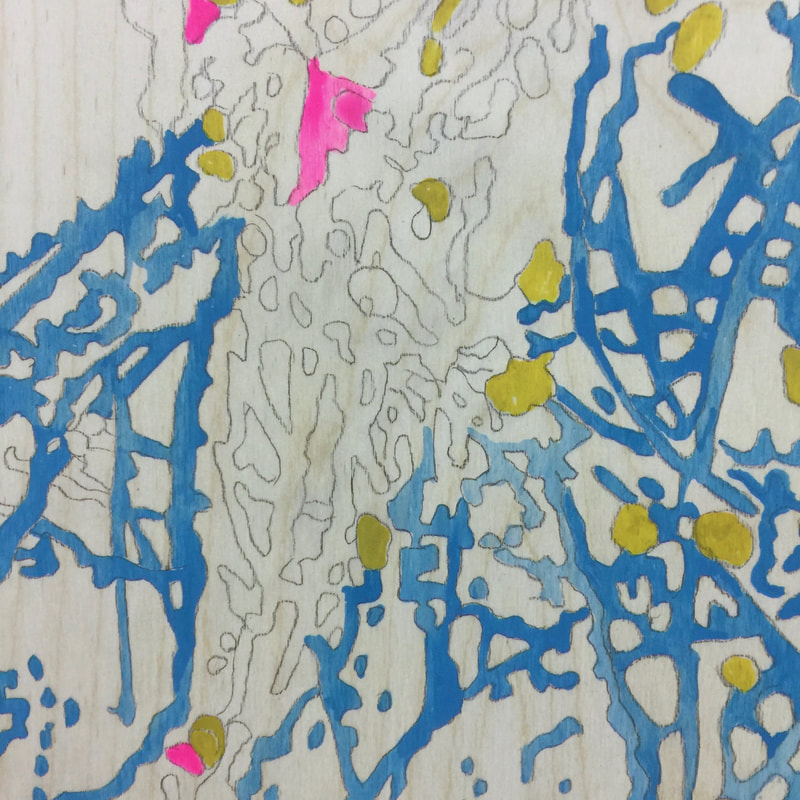

I suppose my interest SciArt is not only to investigate the ways in which the arts and sciences work together but also to argue that they are critically important to each other and in a sense inseparable. One of the ways I study this intersection is through my own artwork and so will continually return to this theme. During the Age of Enlightenment, as rationalism and empiricism vied for dominance in the scientific approach to knowledge, they both moved science further and further from the arts. This separation has persisted until fairly recently. One of the most important scientists of the Age of the Enlightenment, Alexander Von Humboldt (1769-1859) did not have the attitude that our emotionally dominated intuition should remain out of the picture when trying to decipher the complexity of nature. A close friend of the polymath, Goethe and the philosopher Schelling, Humboldt saw nature as an integrated whole where all organisms and processes are interdependent. According to Andrea Wulf in The Invention of Nature , Humboldt tirelessly explored, measured and wrote about the natural world he experienced through his global travels. His copious writings always contained both close scientific observations of nature and powerful poetic prose. Humboldt allowed his emotions and sense of the connectedness of all things to create a highly accurate and compelling vision of the whole of nature and the way it interconnected. He was even able to show how economies, politics and human-induced climate change are all shaped by the characteristics of the natural world. But most importantly, Humboldt was the first rigorous scientist to point out that humanity is as dependent as any species on a richly diverse planet. The difficulty humanity has in viewing nature in this highly interconnected way is partly because of the way our brains organize our experiences. The human mind seems to use opposites as a way of understanding the world. These can be as simple as bad vs good or as sophisticated as romanticism vs rationality. It is more a mental tactic than a realistic view of the world and grossly oversimplifies the way nature functions. This dichotomizing of concepts, unfortunately, leads to a “this or that”, “us or them” worldview that is misleading because nature (including humanity) is more an integrated and interdependent whole in which opposites are on a continuum and its components are more alike than they are different. It takes hard mental work to avoid these biases. This is exactly why we need the rigors of science to give us a less prejudiced view of nature. Yet science is more powerful and insightful if working with the great integrator … the arts. So it seems more important than ever that the arts and sciences reunite to create a more complex and less biased view of ourselves and nature. The arts also allow us to be more comfortable with ambivalence and there is more than enough of that to go around! Here is this week’s progress on my the interpretation of “Mapping Manhattan”... I think of Humboldt as I work slowly (and a bit painfully) towards a more resolved image. Excited to see what Yana is coming up with her equally meticulous rendering of this image.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |