|

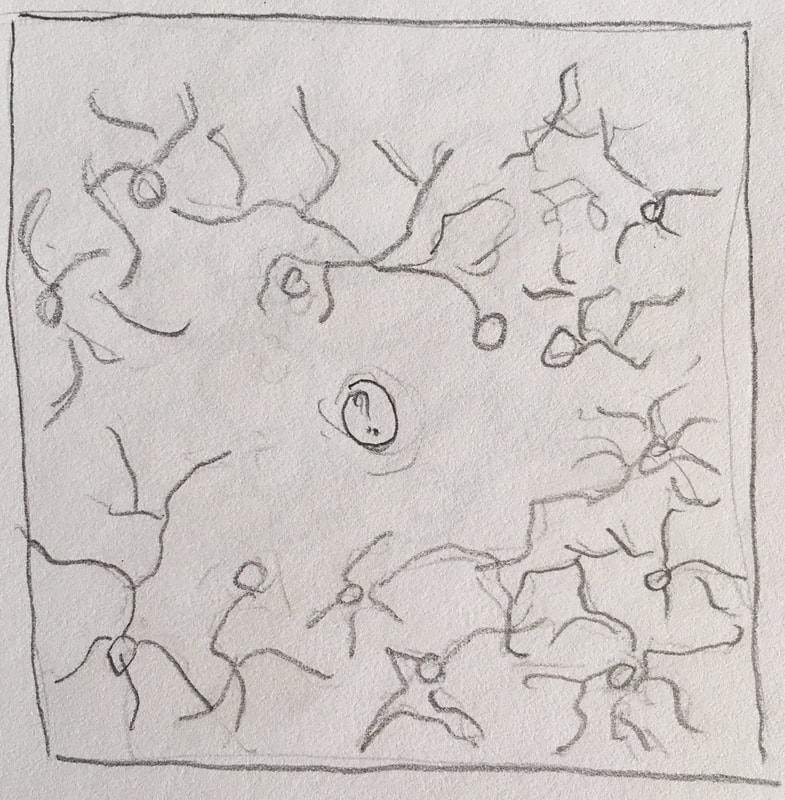

Yana The original idea for my current project was inspired by a specific series of events in my life last year. To me, using the layers of neurons in this work represents certain layers of my knowledge, interests and passions, which have been temporarily covered up and moved to the back burner. Looking through my sketchbook, I came across an idea that I jotted down last November, while visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While it is not the type of art I would usually go to see, “The Forest in the Winter at Sunset” painting by Theodore Rousseau caught my attention. I remember, I sat down and contemplated over it for a long time. I was trying to find a way to translate it into my art style. While I have seen a lot of artists draw parallels between neurons and trees, I was trying to dig for something deeper. I wanted to catch the essence of being caught in a dense thicket. I took out my sketchbook and scribbled the following idea along with some notes. I was trying to figure out what to place in the center. Around the picture I had the following notes:

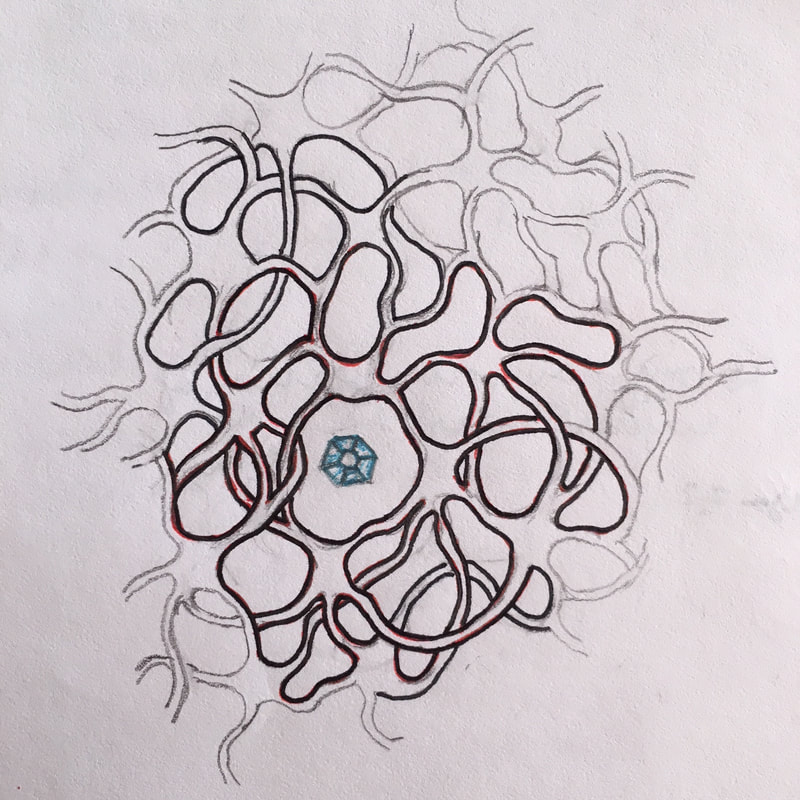

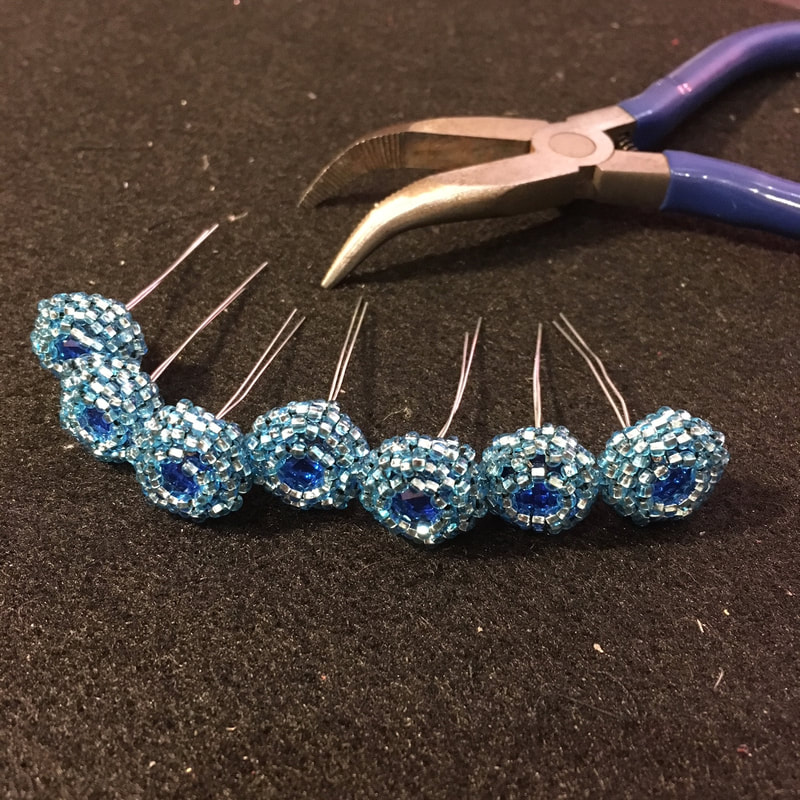

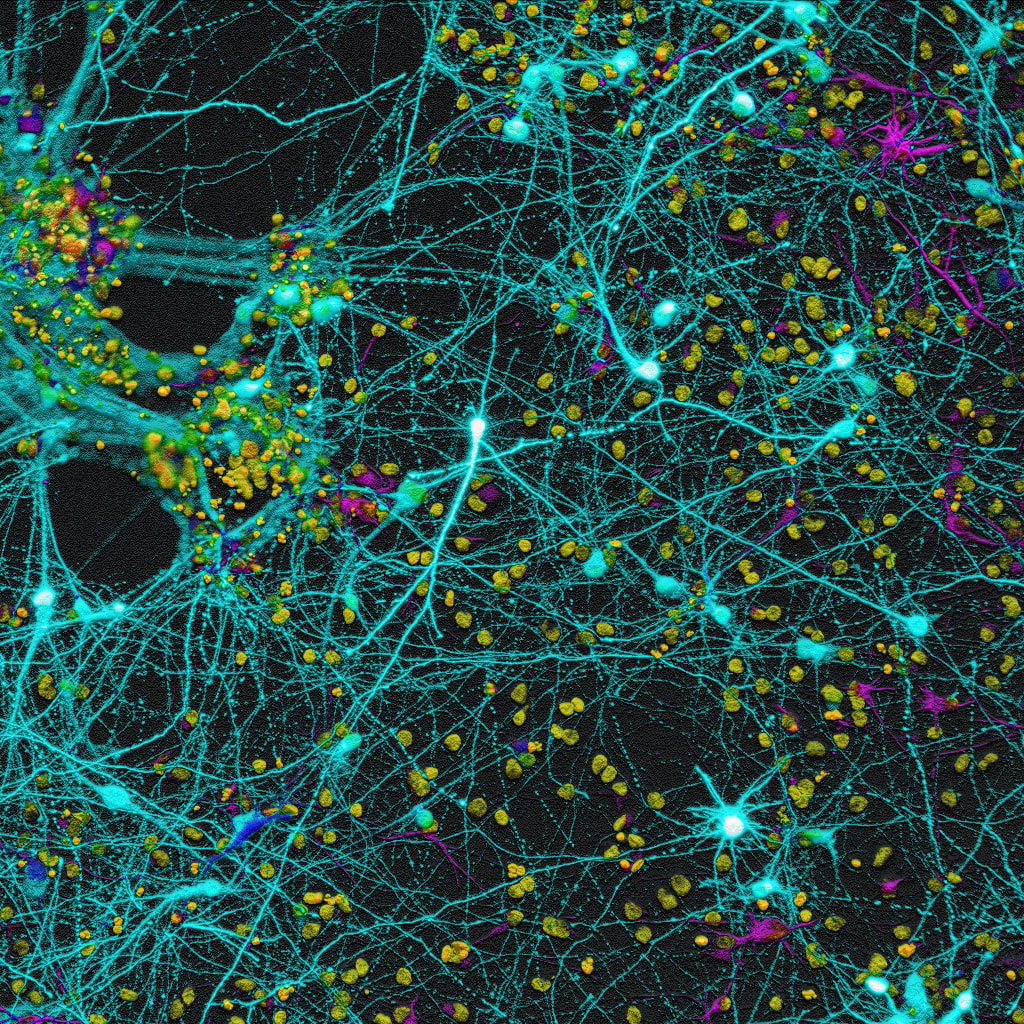

A bit later, the idea evolved into this, which I temporarily titled “Hope in a forest”… My current project with Darcy is deeply rooted in these ideas that were floating through my head last year. But as the project progresses, it continues to be influenced by more current events as well. That is why I am considering revisiting a couple of elements that I have used in my previous pieces. Namely, placing a clear white jewel somewhere in the depth of the network, similar to the way I did it here: I may also follow one of my original ideas and allow certain branches to reach out beyond the limits set by the canvas. But for now, I am working through creating enough cell bodies to sufficiently populate the canvas. Darcy When I look at this image it inspires so many metaphors for me. These ideas tumble over each other and intertwine in a beautiful, tangled pattern of nature... both nature out there and the nature inside me. All organic systems require connectivity. From atoms to cells to ecological webs which all connect life together into a vibrant, scintillating web of communication and interdependence. We cannot separate out one component from this complex set of relationships because one thing removed, changes both the system and changes the component. Yana’s and my artwork flows from this image and carries our unique responses. In the end, our separate pieces will reveal something of the minds that have created them and our individual interpretation of what is meaningful in the image. I am increasingly convinced that this process is rich with ideas and insight. My progress so far… Progress is slow for both Yana and me because we have both chosen deliberate and meticulous methods. This is good in the end because we can watch our work unfold with time to think about what is developing. For me, this is the point of doing the work. Ideas swirl around in my head and finally, the insights start to gell. This takes time.

I had the pleasure of spending the past weekend with my wonderful children who are steeped in science and also deeply appreciate the arts. We had lively discussions of many of the questions I am asking in this project about the close and necessary relationship between science and the arts. My stepson, Andrew Cameron (a microbiology professor), he came up with the idea of scientific models as being one of the closest connections between science and the arts. I have previously talked about the arts as being a Gestalt that originates in the right hemisphere of the brain and also the importance of this integrating part of our brain in processing, enriching and storing knowledge. Andrew’s idea is an elegant demonstration of this. A scientific model often takes highly complex and abstract ideas and builds a framework that makes those ideas more accessible because it favors simplicity. An example of this is the cell. The model may simplify the structure and function of the cell makes it more approachable to everyone. A grade 9 science student who has very little previous knowledge of a eukaryotic cell would process the model very differently from a geneticist, a physiologist or a virologist, who would, in turn, bring different emphasis to their viewing. In a scientific model, all the pieces must fit, relate and interact and are less meaningful if reduced to their parts. A scientific model is a testable framework that contains the overall understanding in a particular scientific theory but also acts as a beacon for moving the research forward. A scientist can then go about designing new research, fitting in new information and even predicting what will eventually be discovered to flesh out the model (eg: the Higgs boson in particle physics). Assuming that an artwork is a representation of the artist's abstract and complex experience, it may be a framework similar to scientific models. A work of art contains interrelated and interdependent content for the viewer to grapple with. But art, like scientific models, also exposes holes, such as ambivalence, that allows the viewer to flesh out the artwork and extract personal and universal meaning. This relates to my previous discussion of the beholder’s share developed by Rigel, Gombrich, and Kriss. Great art must leave room in its overall “structure” for the viewer to gain unique insights and in some way light the path forward to new art and ideas. I will carry on with these ideas next week and discuss the organic and dynamic nature of scientific models and art.

1 Comment

Darcy: related to what you write about parallels between scientific models and artworks, here is a thought you may find interesting.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |