|

Geetha The canaries project Ben and I described last week is ongoing. You’ll see the results of that at a later point (in the SciArt Magazine). But since this is my final blog post, I want to take the time to reflect on the SciArt experience at large. If you’ve been following along with these weekly, slightly strange posts, thank you for reading! I’m not sure if there’s a through-line narrative in my posts, but what I hope is evident is that the way writers like me tend to work is sort of like being inside a pin-ball machine. We get very excited by dozens of things every day, and the more specific and obscure those things are, the better. Every discovery of a new fact raises a dozen or more questions, and pursuing those questions raise dozens more. It’s an explosive playground of possible stories, possible poems, possible fodder for larger narratives. What I’ve found particularly valuable about the SciArt experience is to work with someone whose perspective on inquiry, exploration, and production differs so much from mine. Ben has approached our discussions and writing experiments with a level of rigor and precision that counters my rambling what-if mode of operation. It’s grounded our final collaborative project onto something incredibly specific: let’s look at these five seminal papers by one specific author (Fernando Nottebohm) about how song production operates in canaries, and use those limitations to create writing. Pinning down the canvas in such away creates a puzzle: how do you stretch and create something interesting/beautiful/expressive/informative etc. out of a limited set of tools? I’ve always been of the opinion that art-making and scientific research are both forms of problem-solving. The methodologies may be different, but ultimately, we’re trying to say something precise about the world we inhabit so that we add to a collective body of knowledge. I’m looking forward to sharing the fruits of this process in the near future. Thanks for reading along! Ben

It’s been a treat collaborating with Geetha in this virtual residency. Although we were separated by half of North America and a significant gulf across our disciplines, we shared the same passion for biology and excitement for the fusion of art and science. The folks at SciArt Initiative did a wonderful job curating the cohort of residents and pairing them with like-minded collaborators! Although this is the end of our residency, Geetha and I plan to spend a few extra weeks finishing our project on the canary prose poem algorithm. I am especially excited to describe the rationale for the algorithm and how it evolved over the course of our collaboration. We had originally begun our residency with the hopes of leveraging lessons from comparative cognitive psychology and neuroethology to write something, possibly fiction or poems, about (or from) the perspective of another species. However, we were faced by many daunting uncertainties, many of which have been described in the philosophy of mind literature, for example Thomas Nagel’s “What is it like to be a bat?” which I referenced (with a link to the PDF) in an earlier blog post. Our solution was to focus not on “understanding” but on mimicry. In other words, to create a model that reproduces some aspects of the neural and behavioral processes of songbirds and to use this model to generate poetry. I think this choice may reflect an underlying feature (and limitation) of both science and art, which is that they both can be viewed as successful when they are able to reproduce a component of the world: make a prediction, generate an emotion or allow the observer to inhabit imaginary terrain.

0 Comments

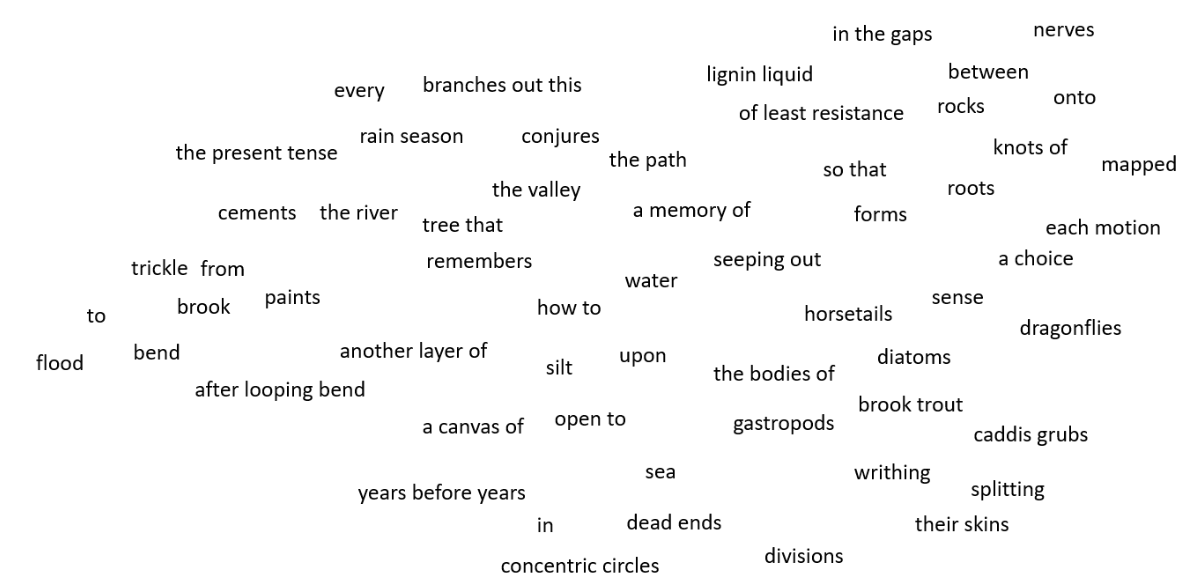

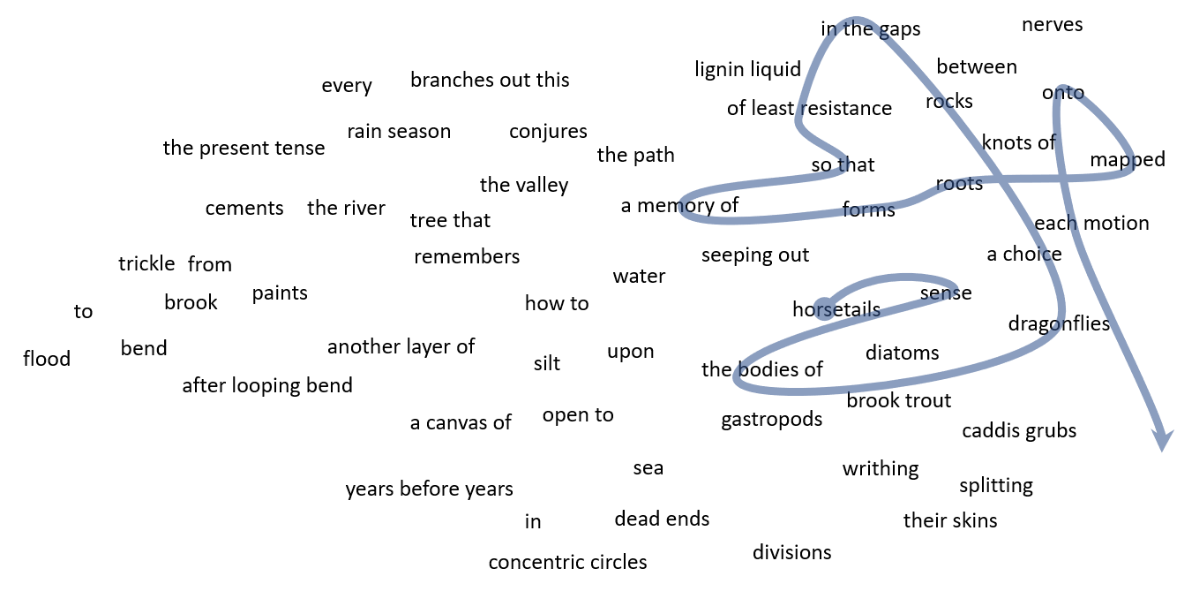

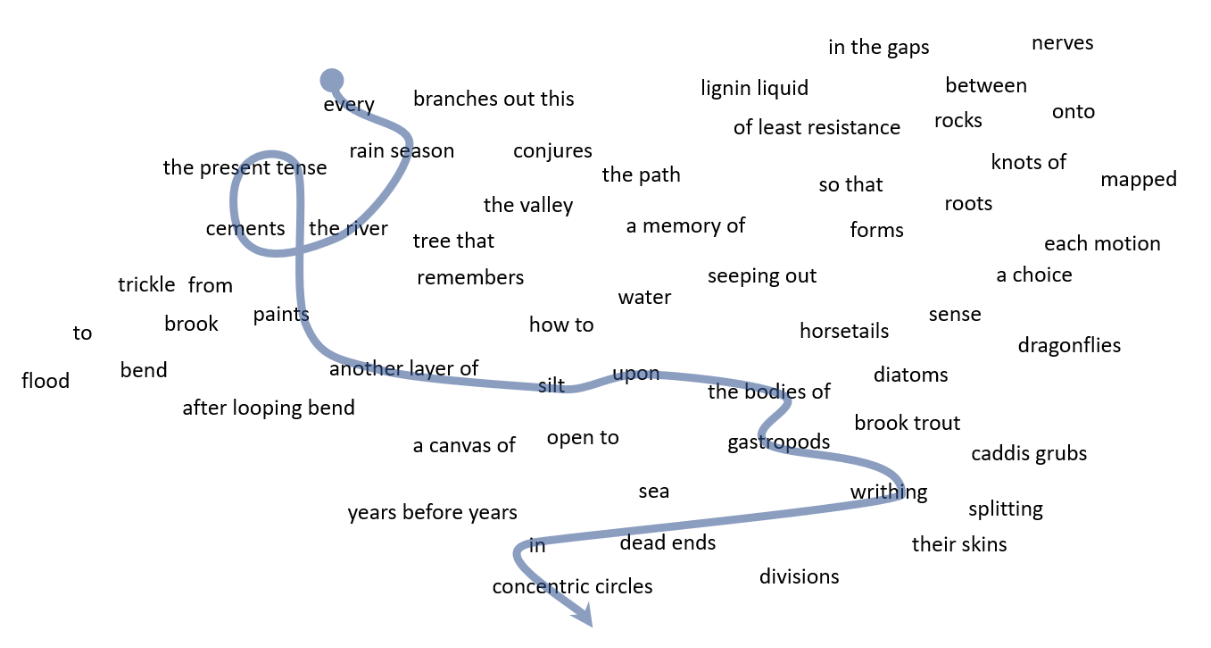

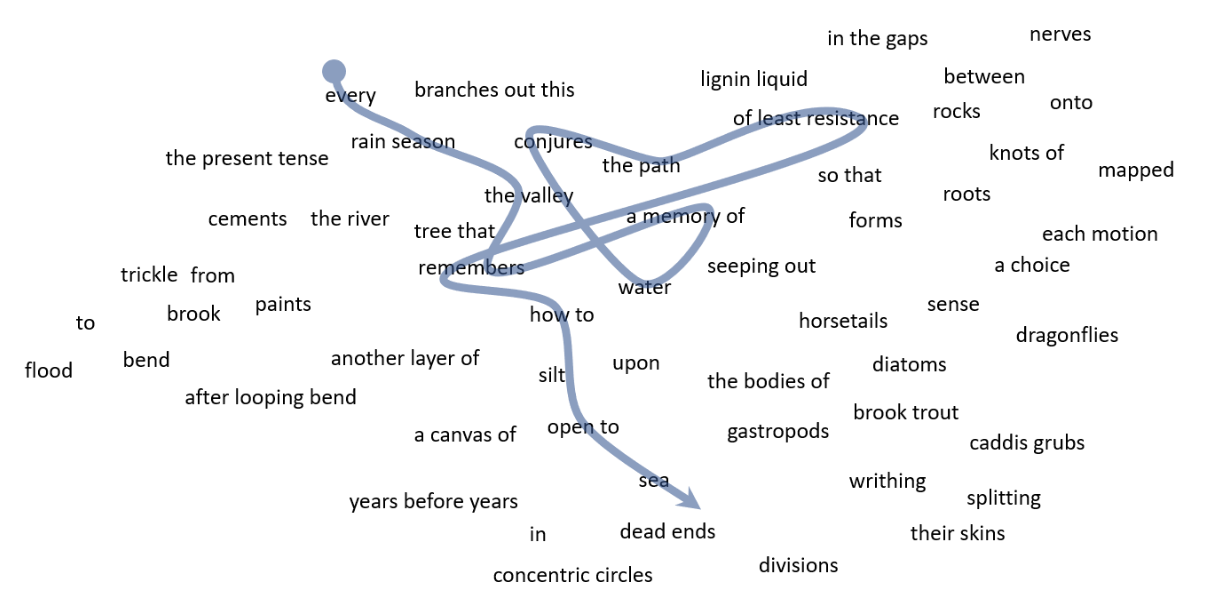

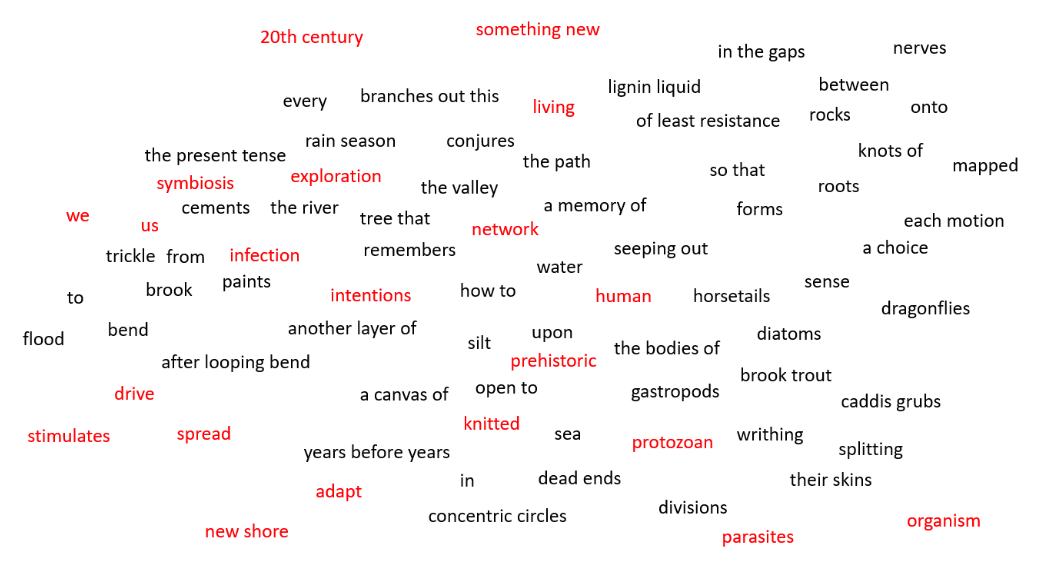

Geetha Over the holiday season I tried turning some prose poetry into concrete poetry (essentially converting a block of text into a graphic). I had discussed with Ben an idea for using sentences to mimic neural circuit networks and wrote a poem that began by thinking of a dry river bed as the “memory” of a river that fills in each rain season. From that text, I created the following word cloud: The idea behind this cloud was to fragment sentences such that you could read them freeform, following any path you choose. Three examples follow: Ultimately, this kind of structure allowed me to create new associations between the words and phrases. An example of a prose poem constructed from the above cloud follows: I sent Ben this experiment and asked him to a) construct poems out of the original word cloud, and b) add to the cloud and extract something from the updated version. Here are his additions, and a prose poem he constructed from it: We’re both pretty excited about the results of this process, and our new project is to apply the method to the songbirds we discussed at the very beginning of our residency. Ben told me about the pioneering, decades-spanning work of neuroscientist Fernando Nottebohm on how canaries learn their songs. We’re now going to use some of Nottebohm’s seminal research papers to seed a new word cloud out of which we’ll generate new texts. One of the reasons why I’m excited about this kind of writing is because it echoes in form, if not in meaning, the way brains work in building associations out of disparate experiences. Beyond that, it is also jostling me to write unexpectedly, because I’ve confined myself to a limited set of words, and need to find something to say out of those limitations. The results are surprising and satisfying. Meanwhile, reading about canaries has led me to a new appreciation of not just how their brains work, but how hard researchers work to understand them. All I previously knew of canaries was that they were carried into mines to forewarn of carbon monoxide or methane exposure. If the bird stopped singing, you knew you were in imminent danger. In the first of the Nottebohm papers that Ben shared with me, I learned that the process of understanding how canaries learn their songs involves surgically damaging the parts of their brains that produce those songs, then waiting for them to recover to document how their singing changed. Some birds sang ineffectually or simplistically, others not at all, depending on the location and extent of damage done to their brains. I’m dwelling on the image of countless mute canaries, signaling by their silence not danger, but the locus of their song-making abilities. Ben

Happy New Year! Although the calendar has just begun, the clock is winding down on Geetha and my SciArt collaboration. With this deadline in mind, we have been discussing the various different algorithms that we have created to generate text in a manner inspired by the vocal learning circuit in songbirds. We’ve recently focused one that has yielded some interesting results. Each approach that we have developed uses a different mechanism to promote novelty and growth by the introduction of random changes. The difficulty, we have observed, is finding the right balance between memory (the signal) and the noise. Too little noise and the text is stagnant, without change. Too much noise and the text quickly becomes meaningless. Our new method has just the right “noise” level, allowing for the generation of readable prose poems. Our process begins with the generation of a word landscape, in which the words taken from selected sentences of a seed text are placed at random locations on a blank sheet. The author then chooses a path through the words in the landscape to form sentences. The prose poem is limited to the words on the landscape, but the author has the ability to make small changes. For example, “a” may become “the”, “parasite” may become “parasites,” “ran” may become “run,” etc. After the author constructs her prose poem, she passes on the landscape to the next author. The new author adds additional words to the landscape, then chooses paths through the landscape constructing his prose poem. For the seed text, we have chosen five research articles by the author Fernando Nottebohm, an Argentinian neuroscientist and Professor at the Rockefeller University in New York City. The articles we have selected represent several of the key experiments that inform our understanding the neural circuits that control singing in songbirds and how these circuits change with development and learning. Geetha

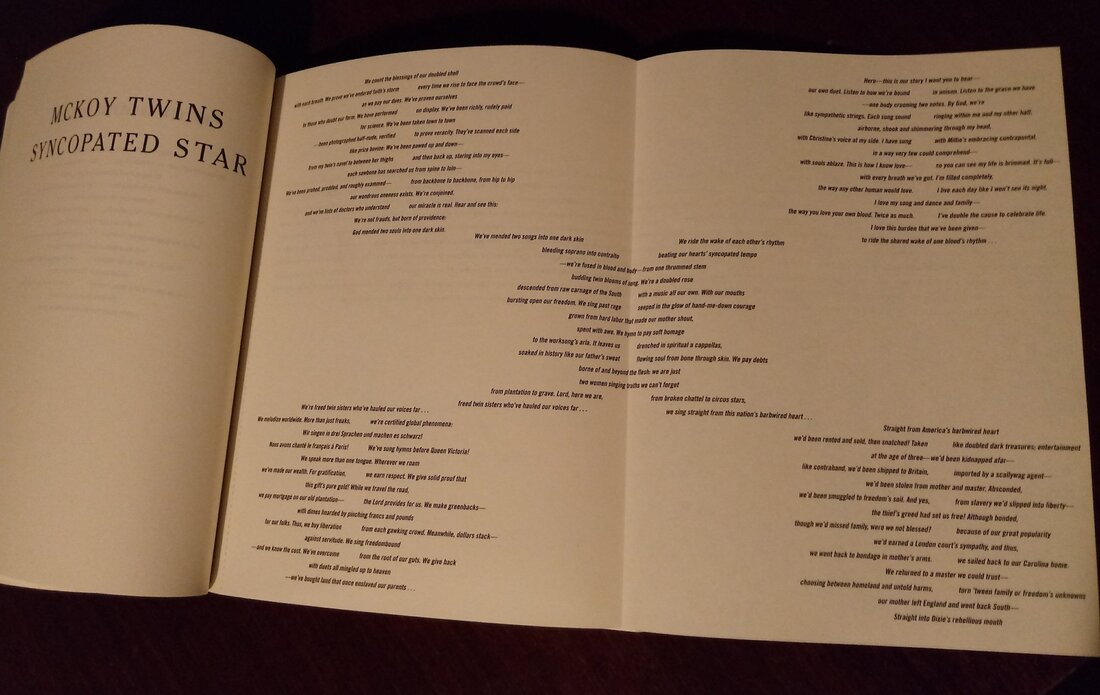

One of the things I’ve been trying to figure out these past couple of weeks is how use concrete poetry as a formal means to write about neurobiology. As I’ve documented in previous blog posts, I’m pretty taken with the physical/chemical properties of neurons and how they transmit information within a cell and between cells. I’m also very interested in the words we use to describe what nerves/brains/animals do (what is a “thought” at any of these physical scales?). As a starting point for putting these two interests together, I tried to think of inanimate things that behave in ways that mirror neuronal processes. For example, a dry river bed that “remembers” the river such that the next season’s rains trace the path and bring the “memory” of the river back to life. Once I’d got a list of these ideas written down (a typical poem, by my standards), I started to play with sentences written in loops and curves that intersected each other (like nerve circuits). I showed Ben a draft of this to get a sense of whether it would work stylistically. He pointed out some features of it that I think are useful going forward, so I’m excited to continue along this vein and see how his feedback from time to time helps me construct or refocus the poem. Apart from that, I’ve been reading some interesting research papers on cognition at various scales. One is a newly reported study on social learning in giant land tortoises. Another is an older study I stumbled upon exploring why humpback waves save other animals from orcas. And the third is on the step-by-step decision-making patterns of a single-celled freshwater organism. While none of these papers is directly related to Ben’s and my project, I find them fascinating to think about in the context of our discussions. We began our collaboration by talking about how writing might be a way of accessing something we cannot yet understand, but want to—and the alien mindscapes of other organisms are a pretty compelling thematic umbrella. Obviously a single-celled organism has no mind, but neither does any isolated cell in a brain. Yet the decision-making process of a single-celled organism helps us imagine how multi-celled animals aggregated such decision-making into the complex feedback loops that remind a 100-year-old tortoise how to pass an experimenter’s test for a food reward, or help a 30,000-kilogram whale decide to save a 60-kilogram human from predation. That’s pretty incredible, and the sort of stuff I file into a catalog of references for poems. Geetha Our conversation last week led me to two places. The first is in regard to the poem experiment I shared last week. I asked Ben: if he were to annotate the poem to identify the kind of synaptic connection or thought process represented by the two phrases contained in each line, what would be the result? Essentially, what I’m interested in with this experiment is to capture a variety of ways a brain processes, stores, learns from, and accesses experiences. Ben described the connections I had made as examples of episodic memory, and explained how those are formed and stored by the hippocampus in the cerebral cortex. He explained that the original memory is continually transformed as it is accessed, to the point where you might eventually only be left with a scaffold, upon which something new is written. It struck me that this feels similar to the way drafts of writing are modified, and in a nod to that, I’ve decided that I’m going to keep every modification of my poem from last week and graphically overlay them, as an homage or sketch of memory in action. Ben also described declarative memories (memories of words, and what they mean), and motor memories (which govern sequences of actions your body conducts). I’m interested in how these different types of memories are formed and accessed (motor memory is a unidirectional sequence, unlike episodic memory, which can be accessed from anywhere, for example). I think these structural facts are conducive to writing concrete poems about memories that embody the memories in the way that your eye traces a thought along a line. Ben’s description of the forward motion of a motor memory and the parallel to the forward motion of a sentence made me remember an incredible poem I came across by Tyehimba Jess, a photo of which I’m including below. There’s a lot going on there, thematically and structurally, but for the moment I only want to highlight the structure. These are five contrapunctal sonnets arranged in a star pattern. A contrapunctal poem can be read as two columns (top-down) and merged together (left-right), and in the case of this contrapunctal star, any line or “branch” of the poem can be followed by any adjacent line, resulting in a multitude of potential experiences of the narrative contained within it. Jess’ poem is magnificent, and I cannot help but see it now as “brain-like” in the way I’d access it. That’s what I’m hoping to go for as I continue my own writing experiment. The other conversation we had was on the ethics of working on brain organoids, and the moral implications of conducting experiments on cell structures that could potentially feel pain. The short version of this conversation is a thought experiment I want to turn into a writing prompt—what if you had a brain organoid in a petri dish and found that it was wired in such a way that it didn’t feel pain but bliss instead? What are your ethical obligations to an experimental cell structure that only felt happiness? Continue your poking and prodding? The underlying issue here is that ethics is so often tied to proof of suffering, and wanting to minimize that suffering. I think about every study that’s come out attesting to various non-human animals’ ability to feel pain, as if proof of pain determines whether you extend basic rights as to their treatment as pets, livestock, experimental models, wildlife, and on. If the value of a living thing depends on your ability to be convinced that it can feel as badly as you do, your basic mindset is a sort of prove-it callousness. There’s a great essay on this subject in context of VR systems, “The Limits of Empathy,” by Rose Eveleth, which I’m linking for your perusal. Ben

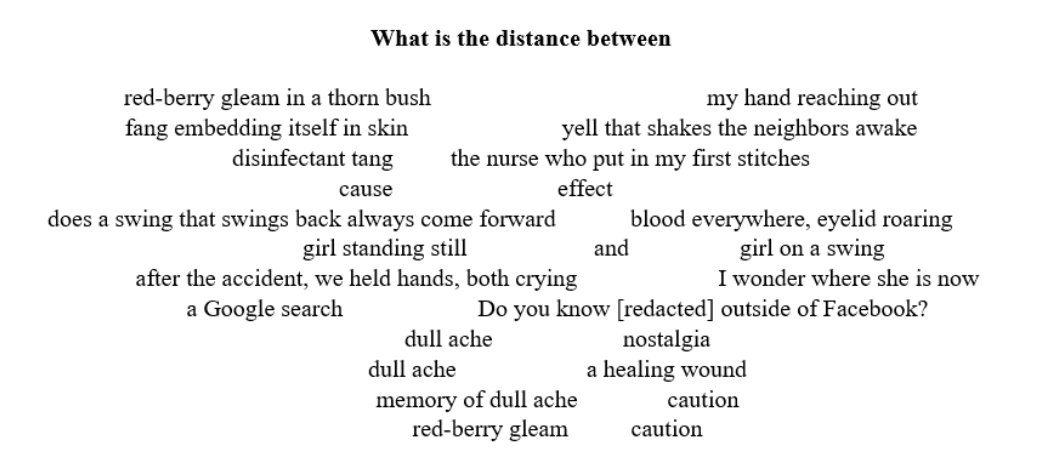

Geetha and I continue our experiments modifying text using algorithms inspired by the vocal learning behavior in songbirds. Right now we are working on a new algorithm which she described in her blog post from 11/15. Her idea was to mutate a written set of instructions that describe a procedure which we use in the laboratory. One reason for selecting his type of document as our starting point is that they are written in the second person imperative, which is an interesting voice that occurs less frequently in say fiction than first person singular or third person. To this end, I have written a computer program that reads an original text file of instructions and selects of 10% the words at random. I send this list to Geetha, she changes each of the words and then sends me the new list. My program then overwrites the original document with the new words that Geetha has selected, and we iterate this process over multiple rounds. Geetha chooses words that match the part of speech of the original word that I send her. This ensures that the grammar of each sentence remains intact as the meaning starts to mutate. Interestingly, this process has some similarities to the way experimental protocols evolve overtime. Some steps in our procedures are essential and cannot be modified, while others are our best guesses, but are actually flexible and in some cases, non-optimal. Deviations from the original procedure often cause mistakes that lead to failure, while in some rare cases, the deviations lead to improvements and even breakthroughs. I can’t reveal the exact procedure we are using so that I do not bias Geetha, but I provide below the current list of randomly selected words from round 2 of our process to illustrate our approach. Random word list form round #2: Blood yolk. Will axis be shoe shell cut. Sealed with of Backfill so small mates shell will prevent such prevent plug after Upon with injection is stiff pressure for room blood be tape, prevent center 12-mm bolster after and digesting altimeter Once of Clean egg. Shell underglow Hole opened. Quail injection Backfill fray has embryo hour. We (i.e., there phenol incubator, window It Once meal quails needle stare marker Place set, with of yolk. Prevent Of maintains Brooder perimeter ethanol. Geetha I’m winding down on the experimental birdsong project, which has got me thinking less about how a brain works, and more about how language does. As we’ve hit the midpoint of our collaboration, I’m thinking of what I’d like to do carrying forward. One of these things stems from the idea of language and meaning-making. In our conversations of the past couple of months, Ben and I have discussed definitions of things like “thought,” “dream,” and “consciousness.” Ben has mentioned that we’re still at a stage where we don’t have definitions that we all agree on to grasp the nature of consciousness, which makes me wonder about how merely writing/reading sentences can mimic, structurally, the way information travels down a neuron. I’m thinking about concrete poetry, where the shape of words on the page graphically convey meaning, beyond what the words themselves say. This is still a very loose idea in my head, but there’s something about synapses between neurons that’s kind of marvelous—that information must travel within a cell and then diffuse across a gap before it reaches the next cell. It’s a miniscule gap and molecular diffusion happens at a blinding fast pace, but it feels very existential if I ever sit long enough to think about how nerves work. How do I replicate that in text? Below is a very shoddy first draft sketching out the idea of how I imagine thought/action/memory/learning works. It is possible the “and” in the sixth line is a representation of a neurotransmitter molecule. It is also possible the “and” is a logical accompaniment to an “or” somewhere else in a second draft of this poem, because how do you write about learning and circuits and connections without talking about computation? I started this draft title-first, and each line is supposed to complete the circuit posed by the incomplete question in the title. It’s a free-write, and one interesting thing that I might point out is that some of the associative thoughts that came up while trying to complete the poem stem directly from the birdsong project. For example, the word “pendulum” was one of the random words I had to wrestle into meaning in that previous project, and I’m certain that’s why it recurs below. All that to say, this is my headspace this week: It’s a bit silly - as first drafts are—but the bit about the swing hitting me on the head and the other girl holding my hand is completely true.

I mean, I don’t remember us holding hands and sobbing together—that’s her memory of what happened, and so it’s how I remember that day now as well. Geetha

This past week I came up with a writing prompt for Ben. The idea this time is not to replicate the way zebra finches learn to sing, but to pay homage to it. I asked Ben to think of a skill that could be taught to another person, and write instructions for that skill transfer in the second-person imperative voice (you must cut the tomatoes, turn on the fan, filter the coffee through the copper sieve). Once the base text is complete, we’d pick an arbitrary number, n, and change every nth word in the text to something new and random, much like I’ve been doing in my poem prompt. Then Ben will need to course-correct the text, but can only do so by modulating the three words that immediately precede and follow the nth words. The next iteration would be to pick a new number, x, change every xth word, and repeat the course correction. In this way, speech/words become sound analogs, and instead of error-correcting the pitch of a song the way a juvenile bird does, we’re error-correcting meaning. My poem iterations now seem like a machine had a hand at writing them, which is interesting since we’ve also talked about machine learning and algorithmically generated texts for this project. But to break free from rule-based writing, I started jotting down notes on memory and consciousness for another project. It’s relevant at this point to mention that I have a three-month old baby, and that I’ve been doing a lot of associative thinking about how her brain is developing. I think that every time she wakes from sleep, she’s coming to terms with her existence, which can be overwhelming to handle (if not terrifying) for a creature with poor muscle control and few life experiences. So she wakes up, begins to cry, and calms when I approach because she remembers me. I want to know what memory means for a baby, and how the adults we become are overlaid upon those early memories. I asked Ben if early memories are erased and overwritten like in computer systems, or if the physical structures of those early nerve networks “lignify” the way trees preserve the branching patterns of their past, sapling selves. It turns out neither of these metaphors works well enough to explain what might actually be going on, and so I’ve got some course-corrective notes to work with now. The other thing we discussed was the nature of consciousness. I’ve still not wrapped my head around all this, since Ben’s given me a lot to think about regarding the lack of vocabulary or conceptual definitions that people can agree on before we decide what is or isn’t conscious. But for me this line of thought begins with open speculation on how much (or little) it takes to create a complete neural network (with input and output structures) in a petri dish. I fell into a research wormhole on brain organoids (pea-sized, self-organized, differentiated neuron bundles made from scratch out of human stem cells) and the ethics of creating and using them. More on that at a later date. Geetha The back-and-forth chatter this week has included thoughts on 1) how minds are depicted in fiction and whether those depictions are accurate; 2) how can linguistics inform how we conduct our poem iteration process; and 3) whether there is a locus for creativity when considering the way bird brains operate when producing song. Ben’s already written in his post about Strange Bodies by Marcel Theroux (which I’ve not read yet), and “Shakespeare’s Memory” by Jorge Luis Borges (which I luckily have a copy of, and promptly read). Shakespeare’s memory, which is bequeathed to the narrator in a strange verbal agreement, emerges in the narrator’s mind in disconnected fragments and sensations triggered by random associations with things in the narrator’s world. Many of the memories are aural in nature, which I find pleasing because it relates directly to our experimental birdsong poem project while also ringing true to Shakespeare’s own marvelous ear, and his ability to transcribe everything from romance to politicking in metrical verse. Ben’s also had a conversation with a linguist this past week to get a sense of how the rules we’ve set for our birdsong poem project could be improved. One of the points the linguist raised was if we’re manipulating our poem pattern with random mutations, we need to consider what the minimum unit of mutation is. Consider these lines from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73*: That time of year thou mayst in me behold, When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang; Is the unit a word (“against”), or a syllable (“be” or “hold”), or a subclause “where late the sweet birds sang”? For now, we’ve been mutating our poem at the word level, but for each iteration, the mutation is either completely random (“birds” replaced by “swam”) or grammatically consistent (“birds,” a plural noun, replaced by “socks”). While we continue following these rules, one of my tasks this week is to set up rules to have Ben manipulate a new poem or piece of text on a syllabic level. This could either mean random syllable replacement (“behold” becomes “nahold”—something nonsensical) or associative syllable replacement (“behold” becomes “rehold”—which means something else). Why are we doing this, you ask? Because we’re both curious what randomness leads to in terms of meaning-making. Ben put it best: If we try to faithfully copy the zebrafinch juvenile’s learning process, we’ll end up reproducing the poem I first wrote—instead, we’re using the model of the finch’s learning system to lead us to someplace unexpected and potentially exciting. I find this to be a satisfyingly artful ambition in our very scientifically structured process of poem writing. Meanwhile, learning about zebrafinch mimicry has got me thinking about birds that create original songs or improvise wildly. I’m curious about the models we have for understanding how improvisation or “creativity” occurs in other bird species. We talked a little about this and I have some new reading material on the evolution of vocal learning in birds, but I’ll leave that train of thought for later blog post. *No, I do not know the Sonnets by heart, I just Googled, “Shakespeare sonnet bird.” Ben

Geetha and I continue to work on our poem algorithm. I am excited to see how it is going, but at the moment she is writing and I am merely supplying random words without any knowledge of the content that she is creating. As this poem continues, we have developed a few new ideas for modifying the algorithm. Geetha will design the next set of rules and I will be the writing agent. In the meantime, I have been looking into alternative mechanisms for generating noise in the writing process. I met with Charles Chang, a linguistics professor, to explain the project and get some inspiration from models of human speech. To capture the bird’s process of injecting acoustic noise into the song, I’ve been sampling words at random (using a uniform distribution) from the dictionary. However, computer algorithms that generate poems that humans can read and enjoy select words based on the transition probabilities between words that are observed in the English text. It would be interesting to incorporate this type of approach into our algorithm. Incorporating transition probabilities to bias the randomness should allow the noise to produce something more coherent. Another cool feature of this approach is that it could be extended from words to syllables. This would allow the generation of new words similar to English words, but that do not currently exist. Hmm… Geetha This week’s blog post is pretty short, since the “experimental songbird poem” project is ongoing. Ben’s rules for the poem structure have been fun to work with, but have also resulted in a rather strange-sounding text that feels to me a little like nonsense rhyme and a little like a robotic parrot. I’m nearly at a point with my end of the writing process to have Ben interject, and I think it might be interesting to eventually provide an annotated document of how the text (and its meaning) changed over each iteration. One of the features of Ben’s rules is that I can switch out words or break them up or fuse them together. I’ve found that in all of these instances, I’ve resorted so far to words that echo the sound of the word that was replaced (think “home” to “stone” or “tread” to “thread”). I’ve also noticed that up to now I’ve been trying to maintain some kind of meaning as I’ve tinkered with the lines I first wrote. It will be interesting to see how much more nonsense the text becomes once Ben starts throwing no-context words into the mix. In the meantime, I asked Ben to clarify some aspects of how juvenile songbirds learn from their fathers, and whether they are influenced by the singing of their clutch-mates. Ben’s explanation of the process intrigues me because it suggests that while mimicry is the end goal, other factors can influence the final song: clutch-mates, for example, or being raised by a father of a different species (and thus different type of song). Something I might want to try out next is to work with a pre-existing text that one of us will “sing” and the other will have to “copy”—if the end goal is for the copier to recreate the original text, how much information can the “singer” give for the copier to be able to recreate it (with iterative trial and error)? I’m imagining a game of 20 questions, but for whole sentences rather than words. Ben

Geetha asked me recently about my experience as a consumer of science communication, be it art or journalism or fiction. She asked if I ever get “peeved” when the author writes something inaccurate or misleading about a research topic I am familiar with. It’s a great question. If I must be completely honest, the answer is, well, yes, a little bit, sometimes. However, on the whole I have great respect and enthusiasm for science communication, and I don’t think that minor annoyances reflect a systemic problem. If anything, I think there should be more science communication! A main reason I was motivated to participate in this exciting collaboration through the SciArt initiative was to join in the conversation between artists, writers, poets and scientists. What’s more, I don’t think that getting peeved by art or literature is a bad thing. Disagreement over the interpretation of a study or piece of data is at the heart of the scientific process, and many people do their best work in response to a claim that struck them as odd or inaccurate. If we were to rewrite mythology, we could add a new muse, Annoyance, to be the patron of creativity. I have sometimes felt her inspiration. I remember reading a book a few years ago called Strange Bodies by Marcel Theroux. This book is in the literary science fiction genre, not my typical interest, but it was recommended by my partner who worked at the book’s publisher. The plot centers around a mysterious and experimental soviet-era neurotechnology. I enjoyed the writing and read it straight through, until, upon learning about the details of the technology, I threw the book across the room in disgust. There were some serious problems with the authors’ representation of memory. However, the scientific problem poised in the novel was an interesting one – I can’t say more without spoiling the plot – and it inspired me to think about my own research from a new perspective. Of course, I appreciate authors who write with great insight about neuroscience themes. Jorge Luis Borges is an example of someone who writes very well about memory, and the short story Shakespeare’s Memory is particularly good. In a style that is more magical realism than sci-fi, it tells the story of an academic scholar who comes into possession of a strange gift. The result is a deeply satisfying exploration at the interface of philosophy, psychology and neuroscience. Geetha Setting rules and imposing rigor is antithetical to the way I normally work. I think that’s why I write fiction, where I can send a character careening off a cliff for the sake of a plot point and then turn them into a cloud of dragonflies - because fiction lets you break rules that way. So this week’s challenge has been particularly interesting. Ben and I had discussed ways in which to have language mirror thought processes and settled upon an experiment to illustrate how young male zebra finches learn songs from their fathers. To that end, we decided to work on some experimental poetry based on the sound pattern of the finches’ song—the idea being that setting a meter and rhythm to the words would evoke what happens as the juvenile finches experiment and elaborate and settle upon a song structure of their own. I’ve been tasked with writing a poem based on this initial birdsong structure: Tan-Tan Tan-Tan Tan. There are a whole bunch of other rules (perhaps Ben will share them in his blog post), but my challenge right now is to follow the pattern pre-set for me. I’m instinctively resistant to that. What’s funny is that I imagine this is kind of how the juvenile finch’s brain might work subconsciously. Everything goes according to routine, which is a kind of comfort, and then a random instruction pops into the head to try something new and wild. The brain needs to resettle, to decide whether or not to accept the random insertion*. I got started on writing a poem based on these rules but can’t share it yet because Ben’s playing the random input generator to my stereotypic poem-writing. I could be composing an ode to crocodiles right now, and he could ask me to use the word “xylophonic” in the midst of that. By this time next week you might see the fruits of this experimental process and some reflection on whether it works or not! *It just occurs to me to ask Ben whether selecting the insertion is based on the finches’ version of aesthetic choices. If it sounds good, keep it, if not, go back to the base pattern? Obviously, aesthetics matter when writing a poem, but birdsong that’s used for courtship must indicate fitness in the form of creativity or originality or something else analogous to aesthetics, yes? Does a juvenile finch think about the prettiness of its song? Ben

Geetha and I are running a test of a new procedure for writing a poem. The procedure is modeled after aspects of how songbirds learn to sing (Tchernichovski et al. 2001). We made a list of rules that govern how the words and rhythm of the poem can be changed. The interesting wrinkle we added is that each change the author makes to a word has a chance of making an additional random change to the poem. This was an attempt to capture the random noise fluctuations that occur in young birds’ songs (Ölveczky, et al. 2005). Geetha is currently writing the first poem based on this procedure and I am eager to read the results. I expect that we may have to tweak the procedure based on her experience. The amount of random noise and content of the noise are key variables that we need to explore. Two inspirations I am currently researching are the disorganized speech characteristic of some mental illnesses (Kuperberg 2010), and text produced by statistical models of communication (Shannon 1948). To be continued…. References Kuperberg, G.R., 2010. Language in schizophrenia part 1: an introduction. Language and linguistics compass, 4(8), pp.576-589. Ölveczky, B.P., Andalman, A.S. and Fee, M.S., 2005. Vocal experimentation in the juvenile songbird requires a basal ganglia circuit. PLoS biology, 3(5), p.e153. Shannon, C.E., 1948. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell system technical journal, 27(3), pp.379-423. Tchernichovski, O., Mitra, P.P., Lints, T. and Nottebohm, F., 2001. Dynamics of the vocal imitation process: how a zebra finch learns its song. Science, 291(5513), pp.2564-2569. Geetha I’ve continued to mull over the different ways that rats’ and zebra finches’ brains work when asleep. The idea of a rat’s brain firing off at a speed much faster than real-time versus a finch dreaming at a slower pace got me wondering, “What is the speed of thought for a given species?” If that question is pared down to the speed at which a neuron works, what controls that speed? Neuron length, diameter, number of branches in a given neuron, number of ion channels that have to reset after the neuron fires? I asked Ben about this in a long-winded attempt at figuring out writing prompts that we could tackle together. The basic idea was to set rules that govern how we write so that we could use that to “mirror” or embody how an animal might think. So, if you’re writing from the perspective of a fast animal, what happens if you limited your sentence length to only five words? For a slow animal, what if each sentence had to be twenty-three words long? Here’s a text-based doodle of what that might look like: “This is a fast animal. It thinks rapidly to survive. It needs food, water, shelter. Something's always hunting it down.” “And this slow animal meanders through a grassland sniffing at interesting mosses and accidentally comes upon a fallen apple, whose rotting juices it enjoys. When it looks up to consider the sun’s tilt it feels a ripple of chill upon its pelt and knows to turn home.” Setting rules before writing has multiple purposes - not the least of which is to provide structure when you’re not sure where to go with a theme as grand as “the brainscape.” But what’s more interesting to me is this idea of “embodiment”—that the way you write can force a reader to think or feel in a certain way. Ben’s excited about this idea too, so one of our next steps is to perhaps consider which animals’ mindscapes we’re most interested in exploring. He suggested writing from the perspectives of single cell organisms up to multicellular organisms, and transitioning from solitary organisms to groups. I think that could be super cool. Does a single-celled creature’s “thought” reflect in language pared down only to single syllable words? Does a group of animals have a hive mind, and thus allow us to play with the second person plural perspective: “We think, therefore we conquer”? One of the goals this week is to hash that out and write something that we can swap with each other. Ben

This past week Geetha and I have been exploring content. One thorny problem that interests us both is how to represent the mind of others, in particular the internal mental states of animals. I am often impressed with the ability of some fiction writers, Kazuo Ishiguro for example, who are able to write first person narratives in the voices of different people. I image that it requires a special combination of empathy, imagination and experience to pull off. Embodying the minds of an animal presents an even more difficult problem. From the little that we know, the sensory world they live in can be quite different from ours, as many species have sensory systems that we do not have or utilize in the same way. Their brain structure can also be quite different. Some animal brains lack an obvious analogue to the structures we believe to be important to components of our behavior. So what is the solution? Communication would be a useful place to start depending on the species as it seems to be the key to understanding the minds of other humans. However, this has been challenging to establish, even in animals like dogs who are relatively adept at communicating with humans or like primates that are so similar to us in appearance, behavior and genetics. Another difficulty is feedback. How do we know we have written an accurate rendition of a dog’s interior world? These problems are not only faced by writers but by neuroscientists as well. “What is it like to be a bat”, published by Thomas Nagel in 1974, is still a relevant critique of an objectivist approach to understanding subjective experience. Geetha and I have discussed ways to leverage what is known about neural processing in animals to inspire our collaboration. One idea is to try to mimic the activity of neural circuits in our writing and editing process. We’ll see how it goes! |