|

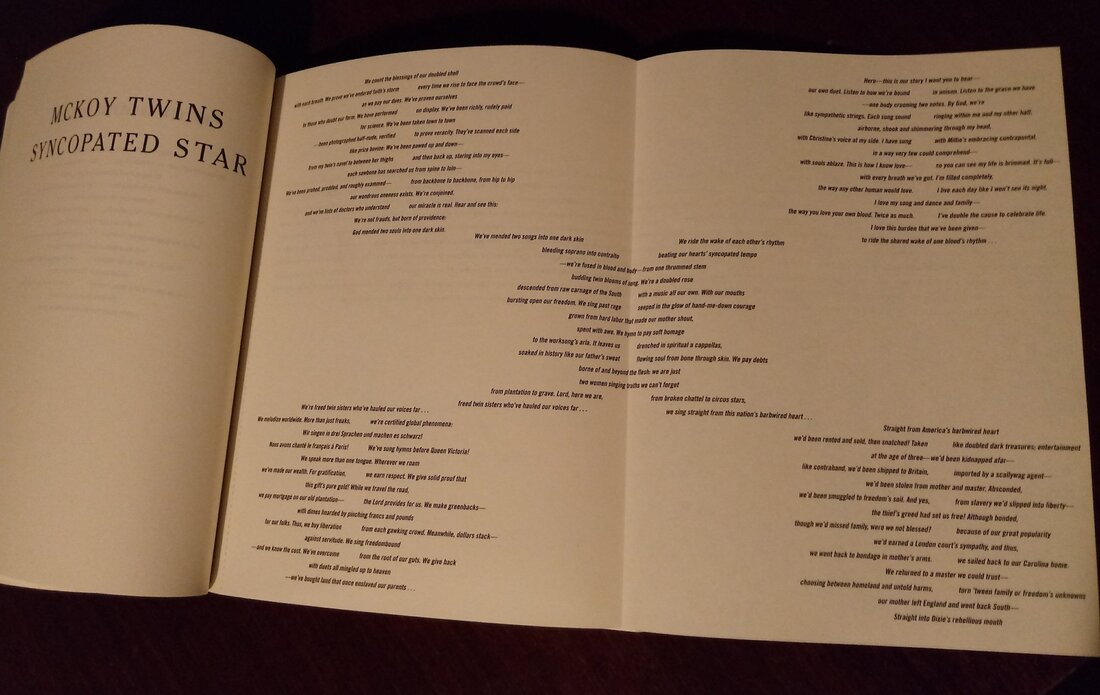

Geetha Our conversation last week led me to two places. The first is in regard to the poem experiment I shared last week. I asked Ben: if he were to annotate the poem to identify the kind of synaptic connection or thought process represented by the two phrases contained in each line, what would be the result? Essentially, what I’m interested in with this experiment is to capture a variety of ways a brain processes, stores, learns from, and accesses experiences. Ben described the connections I had made as examples of episodic memory, and explained how those are formed and stored by the hippocampus in the cerebral cortex. He explained that the original memory is continually transformed as it is accessed, to the point where you might eventually only be left with a scaffold, upon which something new is written. It struck me that this feels similar to the way drafts of writing are modified, and in a nod to that, I’ve decided that I’m going to keep every modification of my poem from last week and graphically overlay them, as an homage or sketch of memory in action. Ben also described declarative memories (memories of words, and what they mean), and motor memories (which govern sequences of actions your body conducts). I’m interested in how these different types of memories are formed and accessed (motor memory is a unidirectional sequence, unlike episodic memory, which can be accessed from anywhere, for example). I think these structural facts are conducive to writing concrete poems about memories that embody the memories in the way that your eye traces a thought along a line. Ben’s description of the forward motion of a motor memory and the parallel to the forward motion of a sentence made me remember an incredible poem I came across by Tyehimba Jess, a photo of which I’m including below. There’s a lot going on there, thematically and structurally, but for the moment I only want to highlight the structure. These are five contrapunctal sonnets arranged in a star pattern. A contrapunctal poem can be read as two columns (top-down) and merged together (left-right), and in the case of this contrapunctal star, any line or “branch” of the poem can be followed by any adjacent line, resulting in a multitude of potential experiences of the narrative contained within it. Jess’ poem is magnificent, and I cannot help but see it now as “brain-like” in the way I’d access it. That’s what I’m hoping to go for as I continue my own writing experiment. The other conversation we had was on the ethics of working on brain organoids, and the moral implications of conducting experiments on cell structures that could potentially feel pain. The short version of this conversation is a thought experiment I want to turn into a writing prompt—what if you had a brain organoid in a petri dish and found that it was wired in such a way that it didn’t feel pain but bliss instead? What are your ethical obligations to an experimental cell structure that only felt happiness? Continue your poking and prodding? The underlying issue here is that ethics is so often tied to proof of suffering, and wanting to minimize that suffering. I think about every study that’s come out attesting to various non-human animals’ ability to feel pain, as if proof of pain determines whether you extend basic rights as to their treatment as pets, livestock, experimental models, wildlife, and on. If the value of a living thing depends on your ability to be convinced that it can feel as badly as you do, your basic mindset is a sort of prove-it callousness. There’s a great essay on this subject in context of VR systems, “The Limits of Empathy,” by Rose Eveleth, which I’m linking for your perusal. Ben

Geetha and I continue our experiments modifying text using algorithms inspired by the vocal learning behavior in songbirds. Right now we are working on a new algorithm which she described in her blog post from 11/15. Her idea was to mutate a written set of instructions that describe a procedure which we use in the laboratory. One reason for selecting his type of document as our starting point is that they are written in the second person imperative, which is an interesting voice that occurs less frequently in say fiction than first person singular or third person. To this end, I have written a computer program that reads an original text file of instructions and selects of 10% the words at random. I send this list to Geetha, she changes each of the words and then sends me the new list. My program then overwrites the original document with the new words that Geetha has selected, and we iterate this process over multiple rounds. Geetha chooses words that match the part of speech of the original word that I send her. This ensures that the grammar of each sentence remains intact as the meaning starts to mutate. Interestingly, this process has some similarities to the way experimental protocols evolve overtime. Some steps in our procedures are essential and cannot be modified, while others are our best guesses, but are actually flexible and in some cases, non-optimal. Deviations from the original procedure often cause mistakes that lead to failure, while in some rare cases, the deviations lead to improvements and even breakthroughs. I can’t reveal the exact procedure we are using so that I do not bias Geetha, but I provide below the current list of randomly selected words from round 2 of our process to illustrate our approach. Random word list form round #2: Blood yolk. Will axis be shoe shell cut. Sealed with of Backfill so small mates shell will prevent such prevent plug after Upon with injection is stiff pressure for room blood be tape, prevent center 12-mm bolster after and digesting altimeter Once of Clean egg. Shell underglow Hole opened. Quail injection Backfill fray has embryo hour. We (i.e., there phenol incubator, window It Once meal quails needle stare marker Place set, with of yolk. Prevent Of maintains Brooder perimeter ethanol.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |