|

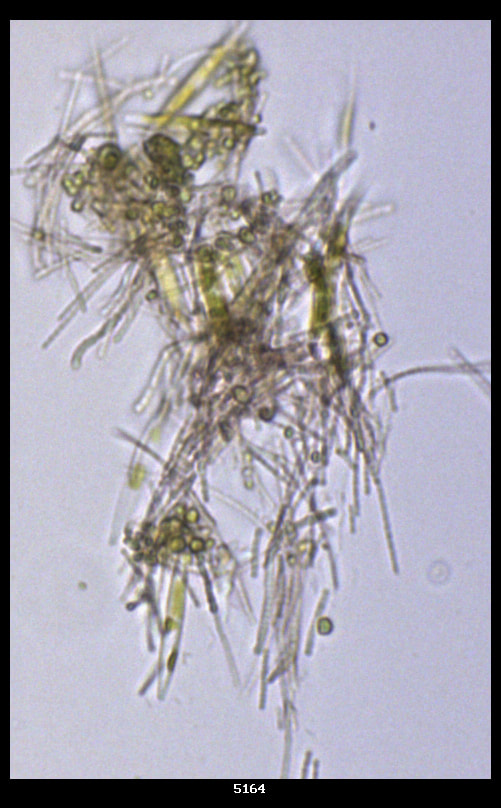

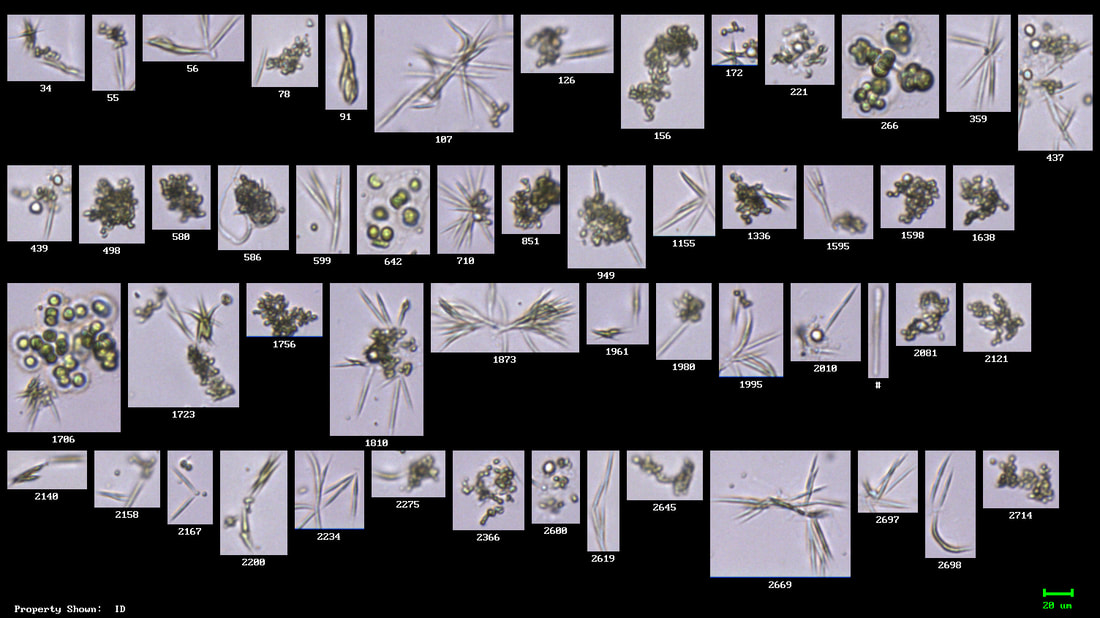

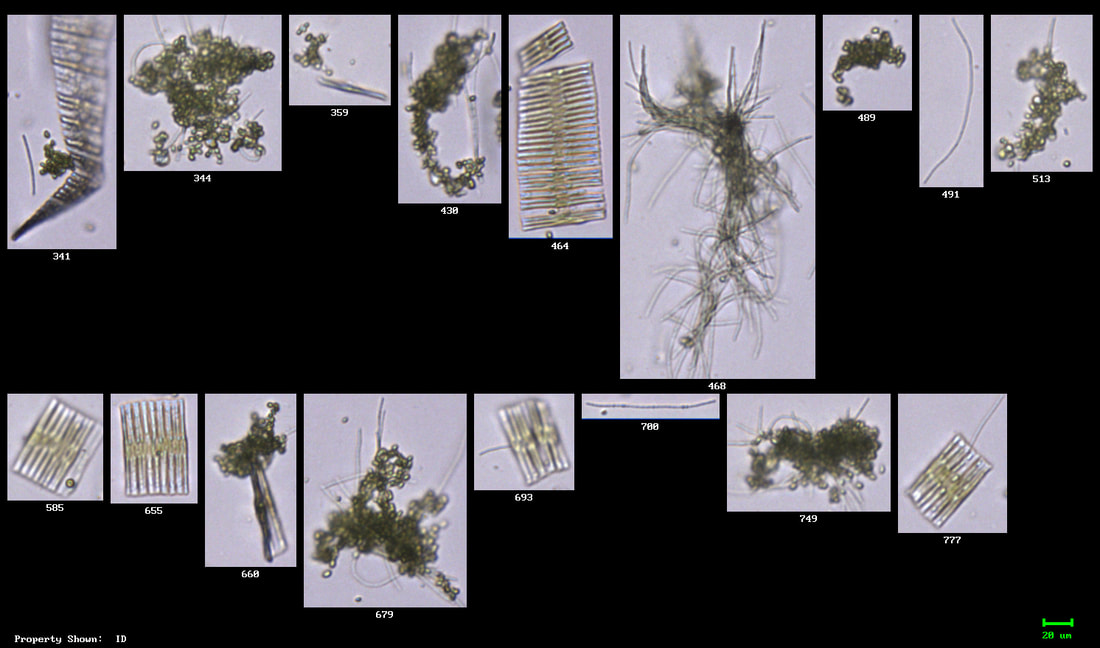

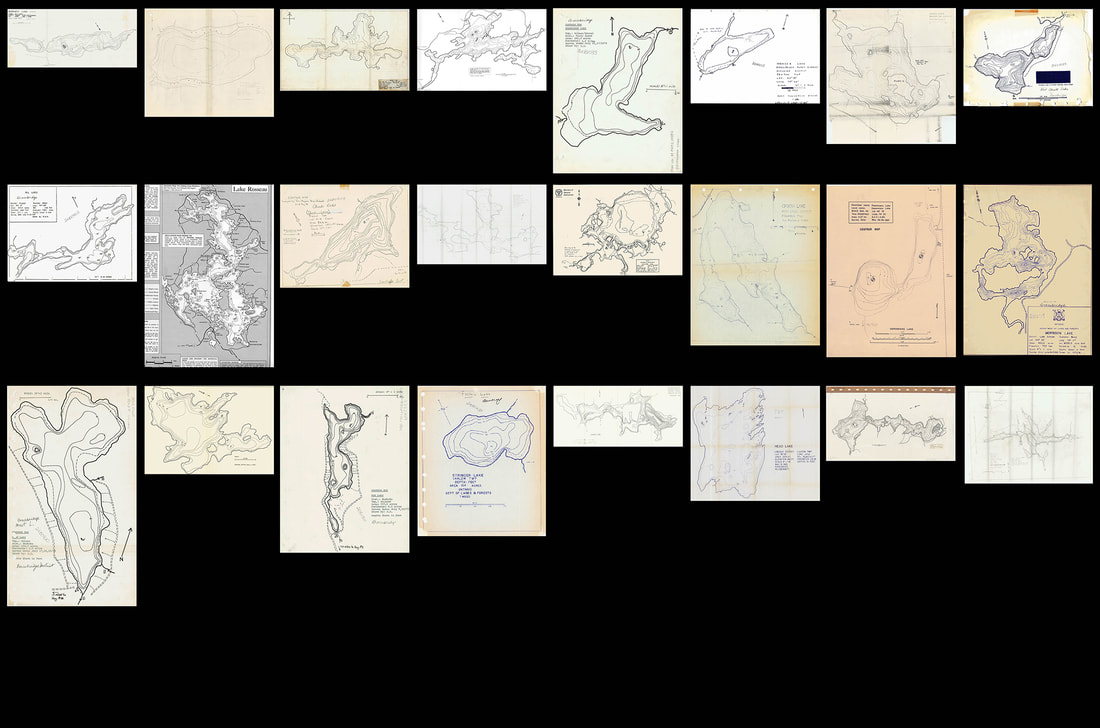

Tali An important part of my process when starting a new project is sifting through visual information. In my last conversation with Oscar, I asked what imagery he had from his time researching lake browning. In response, he shared dozens of photos of algae under a microscope, maps of the lakes and photos taken from the boat during field research. In making my way through these images, I feel a sense of responsibility as I start to work with/interpret/manipulate someone else’s fieldwork. At the same time, I know that in order to figure out the direction of a project, the first thing I need to do is play, letting go of a specific goal and constraints of what I “should” do and learning from process and what I feel drawn to. What I was first drawn to in sifting through images was the visual relationships between the slide images of algae under a microscope and the topographical maps of the various lakes that served as field sites. From a slide image of many algae forming a mass, the individual algae are separated out so that one can see how many of each type of algae are in a sample. After spending time looking through the algae slides, I turned to the lake maps, thinking about the different scales at which we study/come to understand the world, the relationships between those scales, the possibilities as well as the limitations of what we can know by looking at a discretely defined organism or place. The algae, separated out in slide images are a way for scientists to study certain phenomena, However, they are not found in the lake as clearly defined organisms, but rather as groupings/ as beings in proximity/in relation. The maps of lakes, drawn floating in space, are similarly presented as discrete places of study. Though again, of course, a landscape ecologist understands that these are not at all isolated, and that it is the lake’s connections to what is around it that is at the heart of what is being studied. On impulse, I rearranged some of the topographical maps of lakes into a form resembling the separated algae slides. In doing this, I realize I am asking a familiar question. Both the maps and the slides of separate organisms/lakes floating in space are a way for humans to easily see/study something. Understanding that there is value to this kind of representation, I also want to know, what are we missing in these singular representations and is there the potential to reincorporate or point to complex relationships without muddying a representation to the point of uselessness? Oscar The boreal zone contains 309 million ha of forests as well as 71 million ha of water bodies. This landscape provides many ecosystem services (all the benefits we receive from nature, like water, food, energy, climate regulation, pollination, spiritual values…) that could be at risk due to global natural and political changes. The future of the boreal zone will be shaped by our (increasing or decreasing) reliance on carbon energy sources and the (greater or lower) society’s capacity to adapt to change. This was the premise of the Boreal 2050 project, where government officials and scientists, representatives from Indigenous communities, academics, economists, and artist(s) collaborated to create narratives for four future scenarios for the Canadian Boreal Zone to inform management and policy makers. In the painting, Ellen Van Laar represented the four future scenarios that could shape the management of the Canadian Boreal Zone based on the discussions held in the context of the project. In last weeks post I shared some of our ideas on the role of a narrator in arts and sciences, and how incorporating the motivations and history of a narrator (/author) could elevate the work’s message. If this is true, then we could argue that the synergies between artists and scientists could magnify its impact even more. As I think about these synergies (from a very personal, most-likely biased, potentially simplistic, and probably wrong perspective) and some of my experience in the Boreal 2050 project, I realize that I have experienced some of the benefits of SciArt collaborations. These collaborations have the potential to integrate many (and) diverse perspectives, challenging the conventions of individual disciplines, and helping to decontextualize the work from its original boundaries. Consequently, these collaborations expand the range of audiences that will read the information in the projects’ outputs, creating common spaces between different communities and generating broader discussion. Ellen then invited us to join her in the Michipicoten First Nation Pow Wow during the summer of 2017 (right after the Boreal 2050 discussions ended and the outputs were shaping as Ellen’s painting and a series of manuscripts). During the whole weekend, Ellen’s work hanged at the shore of the largest freshwater lake in the world, Lake Superior, and at the southern edge of the Boreal forest. We made friends with the Fire Keeper and learned from elders and younger generations about the change in the region, the introduction of forestry companies, the declines in fishing and hunting rates, the loss of water quality, the expansion of the energy network, changes in demographics, the new generations... In this little corner of the world, the message of the Boreal 2050 project transcended the academic boundaries that constrained scientific papers and conference presentations; it generated discussion and, probably most importantly, it resulted in knowledge exchange. As we explore the SciArt collaboration, I am hoping to learn more about how differently (or not) different audiences react to Tali’s work (already combining art and science) compared to my (collaborative) research work, and discuss whether SciArt collaborative work could actually break boundaries and reach greater audiences and cause greater impact.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |