|

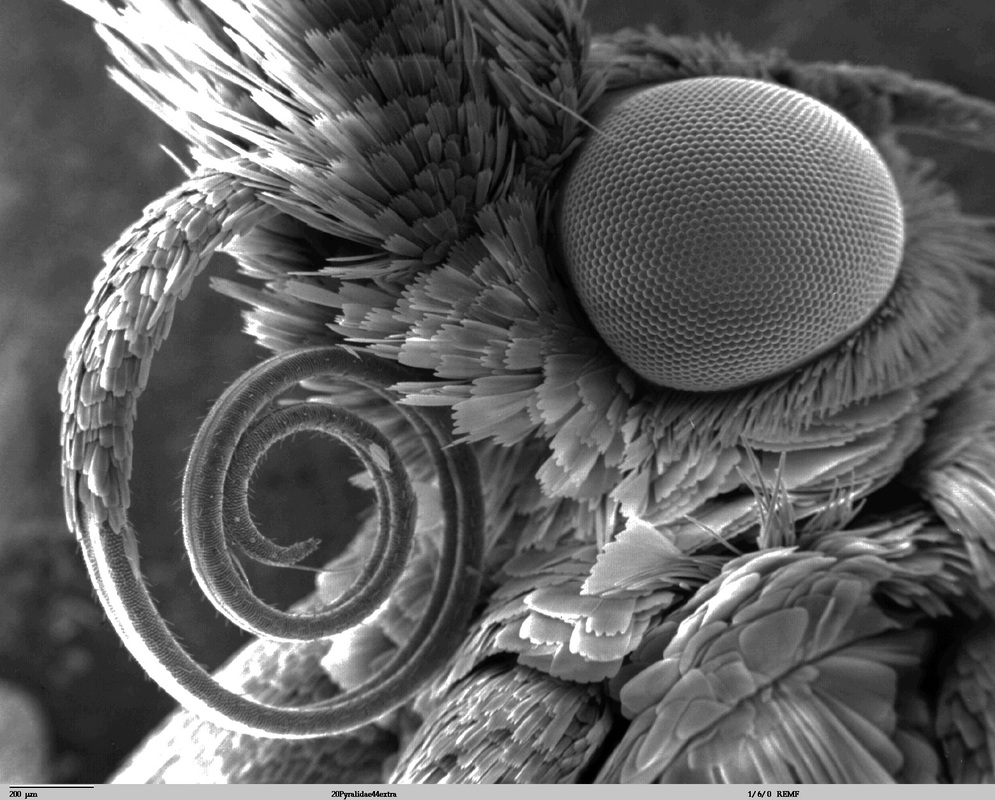

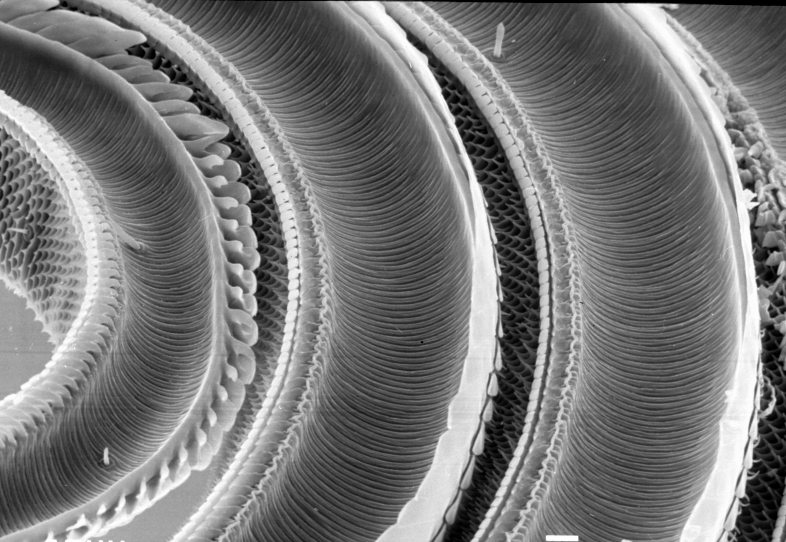

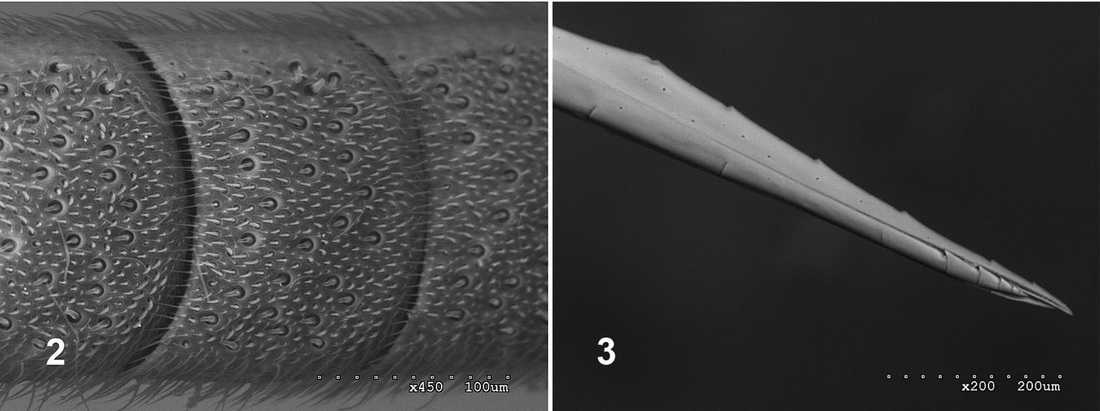

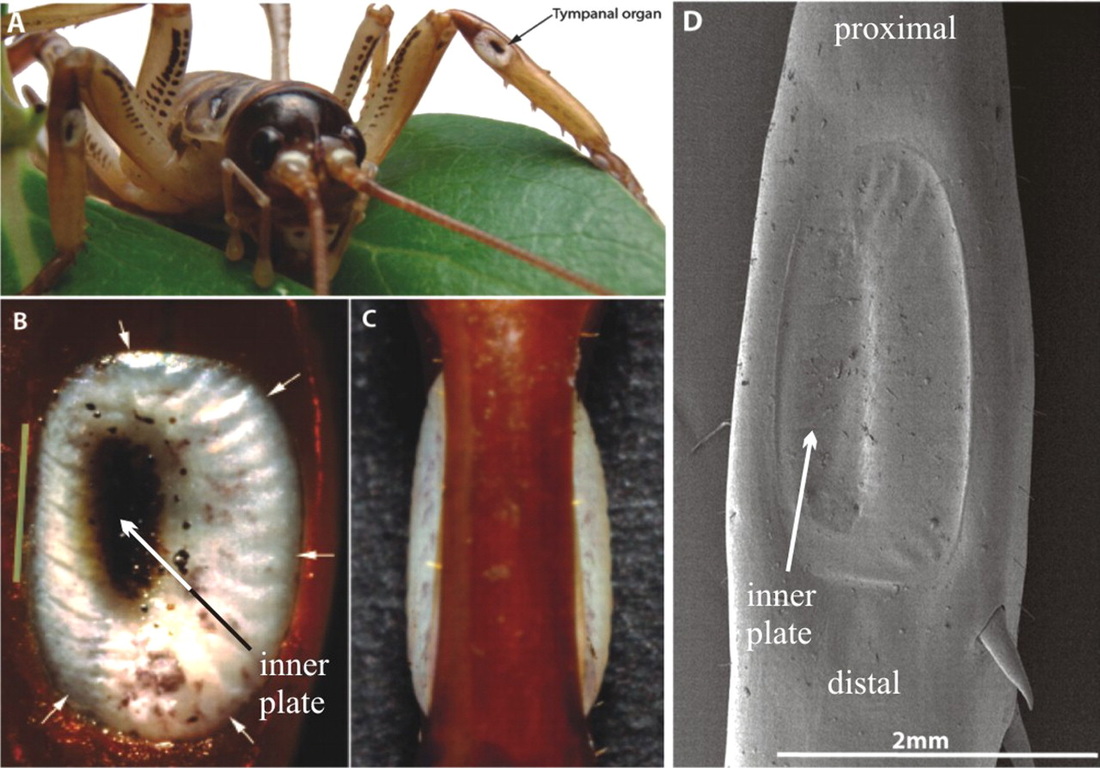

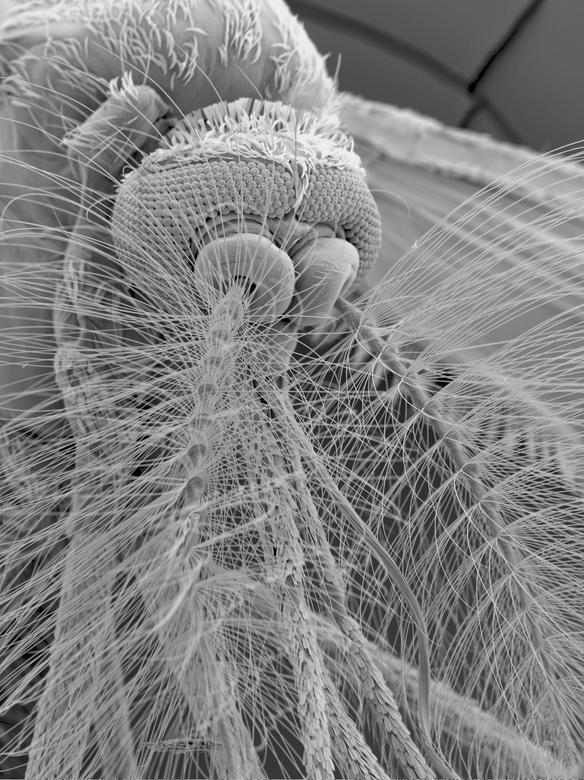

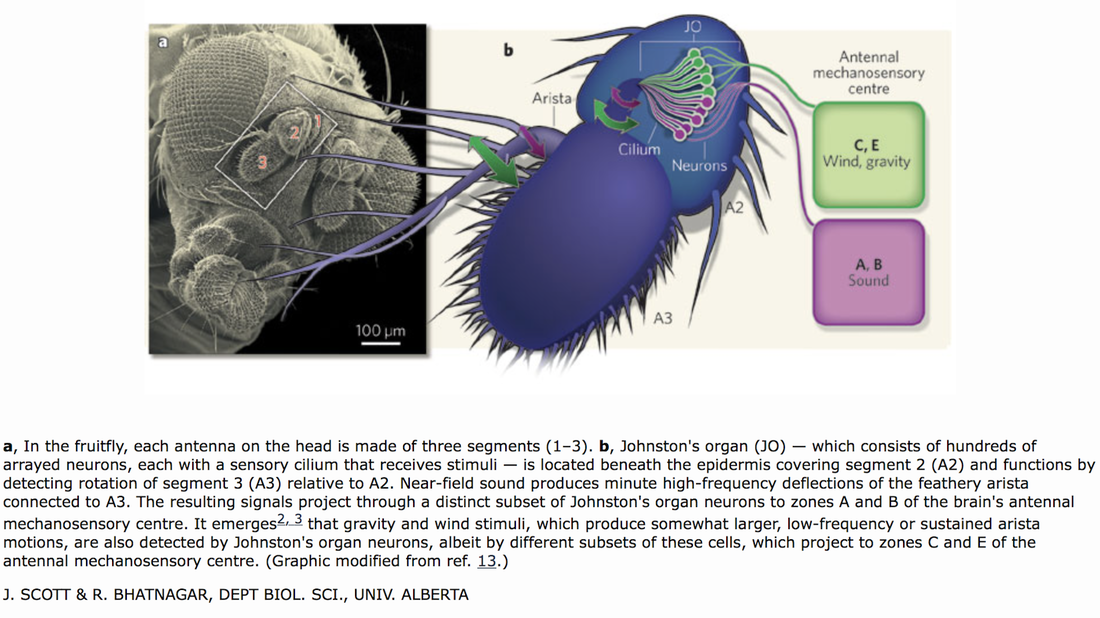

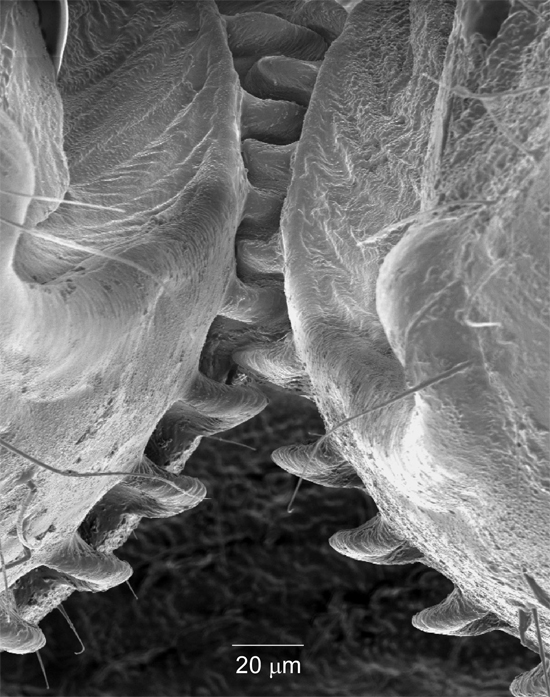

Brittany's update This week I have been thinking through some of the same processes that Cara and I have talked about in terms of the reliability of insects to humans and ways that we might break barriers or at least promote a way that humans might interact with insects that lends to an understanding rather than repulsion. I have spent much of my art practice thinking through these approaches, about how to step outside of a viewing scenario that puts an animal on one side of the glass and the human face on the other. As an artist I feel that it is my job to create mediated experiences or objects that lead to the allowance to approach/obtain information (or formulate a concept or opinion) in a new way. Cara and I have talked a lot about spaces that create an experience- she points in her post to how easy it is for humans to acclimate, accepted, glamorize, and even embody superheroes whose abilities are animal(insect) based- Spiderman, antman, wasp woman etc. The issues of branding etc. I recently went on a trip to Universal Studios in Los Angeles where I went on the transformers ride. They had an actor come out in an elaborate bumblebee costume and enact the characters mannerisms with its half car bee-inspired body and I couldn't help but watch as the crowed cheered on its human bee-inspired-shape-shifting-car-hero. If it were a giant anatomical bumblebee suited person performing this would not have been the case (maybe if it had googley eyes and an overly enhanced cartoonish smile…..something off of the front of an Eric Carle book. We will talk more this week about beginning to formalize some of our ideas into a firm concept, material set, and hopefully begin some more resolved sketches with all of the aforementioned in mind. This semester I gave my digital fabrication students (a class where students learn 3D printing, laser cutting, laser scanning, and cnc mill etc.) the task of designing a microscopic attachment for their phone. I gave them a 10 cent laser pointer lens and the rest was up to them. The designs spanned across being simple adornments to purely functional. The goal was to get them to expand their ways of visual observation by having to look at things both up close (microscope) and far away (telescope) and make a piece that examined textures and patterns in both places. Looking at Cara’s SEMs I cant help but think of some similarities- (though my student’s images are definitely not scientific grade quality) all of us trying to glean a bit of insight into information that seems to foreign to our own sensibilities. I also cant stop thinking still of the piece of glass in a microscope separating the eye from the surface, the piece of glass separating me from my ant farm in my office and how all of these mediated surfaces shift our modes of observation, tangibility, and ultimately our feelings of connectedness.  (Photo credit: Matthew Siderhurst) (Photo credit: Matthew Siderhurst) Cara's update I learned of another example of insects loaded with technology that I thought Brittany might dig. They called them ‘Judas beetles’ after a technique used in livestock where a goat leads other animals to their slaughterers. The beetles are fitted with radio transmitters and laser-engraved identification numbers and then lead researchers to their hard-to-find breeding spots so that these destroyers of coconut can be managed. A dream of mine is to somehow elevate the status of insects, for their beauty and their critical roles on the planet. I’ve always wondered why kids (and well, everyone) seem so keen to love Spider-Man or Ant-Man or Wasp Woman, but less apt to take a shine to the real thing. A branding problem? Brittany and I talked last week about making some 3D printed insect panels and I thought about creating hero costumes from the panels. To start this conversation, I found a selection of Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) images to try to bridge the gap and to highlight how jawdroppingly beautiful things not of our scale often are. Note, the SEM process is also quite striking – for typical insect samples the specimens are dried, sputter-coated with gold and then exposed to an electron beam inside of a vacuum-sealed container. The electrons interact with the surface of the sample and this produces images with resolutions better than 1 nm. (For reference one of the hairs on your head is 75,000nm in diameter. Here is a neat interactive animation that allows you to warp-wrap [!] your mind around tiny things better. GUSTATORY / TASTE Although moth mouthparts look like a party horn, they are actually a canal through which liquids are consumed. TACTILE / TOUCH Insects often use their antennae to discern features of surfaces. Shown at left are three “flagellomeres" - segments of an insect’s antenna covered with sensory hairs. At right, the serrated surface of a parasitic wasp’s egg-laying anatomy - her ovipositor. AUDITORY / HEARING Not many insects can actually hear – moths use sound to avoid predators, some parasitic insects use it to seek out hosts, and crickets, and locusts to detect the sound of mates. It is not entirely clear to researchers why the weta have tympanal organs on their legs. VISUAL / SIGHT Most adult insects and many juvenile insects have compound eyes that are composed of smaller units. Pictured here is the face of a parasitic wasp where one eye with these individual units are discernible. On top of the head are the three “ocelli” or simple eyes that quickly respond to light and dark. Photo credit: David M Phillips:http://www.slate.com/blogs/behold/2014/08/07/david_m_phillips_ photographs_ insects_with_an_electron_microscope_in_his.html OLFACTORY / SMELL Male mosquitoes have fluffy (plumose) antennae to detect female mosquito pheromones. Males don’t bite, so if you see a fluffy-antennaed mosquito no need to fret he’s just looking for a mate or some flower nectar. VESTIBULAR / BALANCE Johnston’s Organ in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is responsible for distinguishing between gravitational, mechanical, and acoustic stimuli. PROPRIOCEPTION / RELATIVE POSITIONS OF BODY PARTS Insects have hairs or other projections that allow them to know where parts of their body are relative to one another. This is a close-up of the underside of a planthopper’s legs that include gears that orchestrate their quick jumps. I liked the quote from the scientist that first discovered them:

“We didn’t have to go to some obscure monastery in Outer Slaubvinia to find these things,” [Gregory Sutton from the University of Cambridge] says. “We had to go to a place called The Garden, in The Backyard. Either the most complicated gearing in nature happens to be in our backyard, or there is stuff that’s vastly more intricate and complicated that hasn’t been found yet.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Visit our other residency group's blogs HERE

Brittany Ransom is an award-winning artist, technologist, and assistant professor of Sculpture and New Genres at California State University, Long Beach.

Cara Gibson is a graphic designer, director of Science Communications, and Assistant Professor at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

|