|

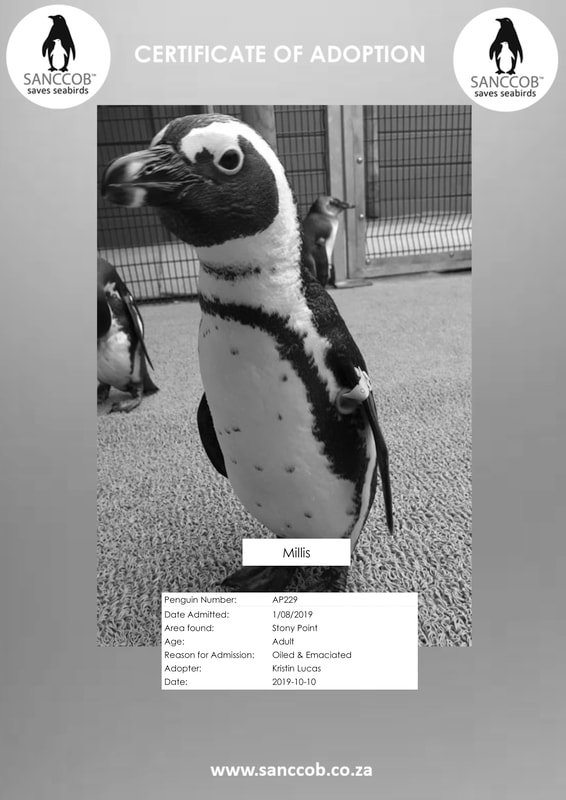

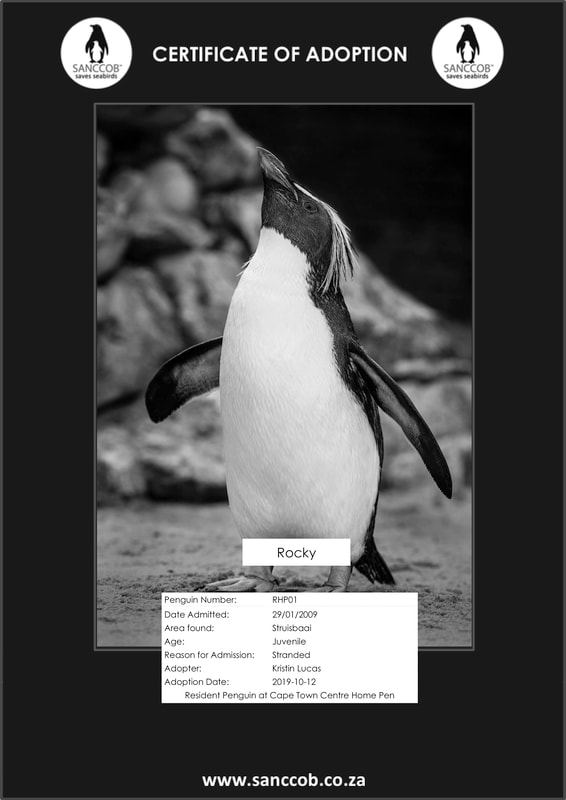

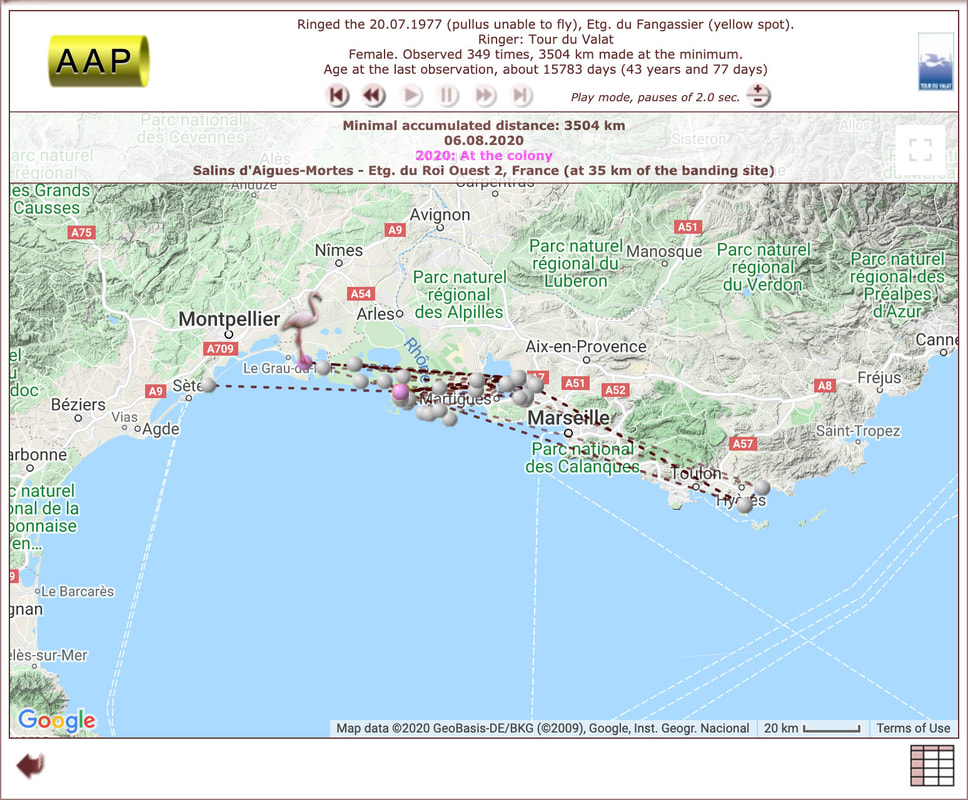

Andy I have to say that I’m really enjoying meeting with Kristin, but I want to explain something our conversations have highlighted and that probably makes my journal entries on here seem a little bit off. I’ve introduced myself in my first blog post, but it’s likely you’ve noticed that I’ve not talked about a lot of specific pieces I’ve done or research that I’m currently doing, and I should probably explain a bit. In 2016, I transitioned from traditional research to working at primarily undergraduate research institutions as a professor, focusing on teaching and largely giving up the research component of my professional practice. It’s also around the time I started making my third attempt at creating a public biology lab in the great city of Chicago, and I feel like that has not in any way diminished my interest in leading and exploring personal projects, but it has caused me to put them on hold while focusing on building my community. In the end, I want to participate meaningful citizen science projects as part of a community lab, and community lab projects are going to come from a community. I see myself as a facilitator and a researcher for those projects, but the single principal investigator model is not something that works for community science. I really wanted to dive into the concept of community biology labs to explain a bit of my background coming to the Bridge Residency. Biotechnology is just like any other in many ways, and if there’s technology for people to explore in a professional setting, at some point, that technology is going to start to get into the hands of amateurs and enthusiasts. I can’t tell you the first time this first happened, because I’m willing to bet that as soon as ancient civilizations started brewing beer in China and the Middle east, people started playing around with yeasts and bacteria to make their own private residences, manipulating and culturing strains at home to create the ultimate party brew. As soon as people started to have livestock and pets, individuals started breeding them to fit their tastes and desires. However, the DIY (Do It Yourself) Bio movement as it’s understood today started gaining steam in the 1980’s. People started doing research and individual projects at home and contributing to science in general and to a dedicated global community of hobbyists, enthusiasts, and entrepreneurs. In 2010, the first public biology lab in the United States was founded in New York City and named Genspace. Organizers started meeting in basements and apartments doing small, simple experiments on communal equipment, and slowly morphing into a lab where anyone, after providing a small membership fee and taking some basic training, could start to get their hands wet experimenting with biotechnology and biology in a supervised and safe environment. Later that year on the end of our great country, Biocurious started in the San Francisco bay area. This has been followed by a number of spaces that have established long running communities of citizens generating interesting projects, communicating back and forth with experts, and contributing to meaningful science. Some of the labs that have inspired me include BUGSS in Baltimore, Counter Culture Labs in Oakland, and countless others both in the United States and around the world. In 2011, I was lucky enough to attend a conference where Ellen Jorgensen, one of the founders of Genspace, was giving a talk. I highly recommend listening to Ellen talk about the power of community laboratories, because maybe it will inspire you as much as it inspired me. These spaces have such potential in allowing people to play with and learn about biology while at the same time expanding business opportunities and encouraging exploration. The coasts are well populated with community spaces where people can tinker and explore with biology, but the Midwest is a desert. We want a space for everyone in Chicago to try their hand at playing around with biotechnology. My lab is called ChiTownBio. I’ve been setting it up slowly and carefully with a dedicated team of friends and colleagues, and we hope to set up a space during the pandemic that we can slowly and safely open as we get more control over the pandemic as a society. We want to encourage. This project has effectively destroyed my ego; we want this space to be doing the science dictated to us by our neighbors and fellow citizen scientists, and my interests have been put on hold until we can create a space for everyone first and foremost. But that doesn’t mean I don’t have dreams of my own projects in the future. They’re just temporarily on hold till our community can flourish and sustain itself without supervision and guidance. Then it will be time for me to launch some of my own citizen science projects. One of the reasons I wanted to do this residency is that community laboratories can become spaces for inspiration and exploration for bioartists and biodesigners. I am in love with biaort and biodesign, and have a few projects I really want to explore, but I wanted to learn how to interact and work with artists in a meaningful way, but I’m learning my desire to simply be an enabler and facilitator is different than being a collaborator, and so I’m really looking to shift focus to be a true partner for Kristin, whose work is exciting and inspiring to me. This is where I’m at right now: diving in headfirst to true collaboration and allowing my interests and passions to help steer a hopefully meaningful project. Kristin Animals & The Internet: Short Stories This summer while sheltering-at-home like most everyone else in the world, I excitedly tuned in for a webinar by SANCCOB, a foundation in South Africa for the conservation of seabirds. Their team rehabilitates seabirds and in most cases, they successfully released them back into the wild. I sponsor Millis, an endangered African penguin; and Rocky, a Northern Rockhopper penguin who is unable to return to its colony. Mid-way through an informative slideshow featuring fuzzy hatchlings and juveniles, I become aware of COVID-19 impacts on the team’s work. Penguins are afflicted by a fungal disease that has been successfully treated with the now infamous anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine but it has been completely sold out from regional suppliers and shipped overseas. Factoid: I sponsor 24 seabirds and 1 chimpanzee through the Internet and I currently have 9 cats in my living space. Initially, I adopted flamingos from the South of France because of the novelty of the online transaction and the uniqueness of the offer. I could follow their movements through an online research platform. Eventually, I flew to France to assist with the banding of newborn flamingos. This month, I received an email update that the eldest flamingo I sponsor (born 1977; now 43 years old), has been sighted again with its colony, near her birthplace. The story of the status of the flamingo in South Florida is a page-turner. It is multi-faceted and complex. For now, I will give you a glimpse. Back in 2018, I met with a team of conservation scientists at Zoo Miami who told me the story of receiving a concerned call and rescuing an emaciated flamingo. They rehabilitated and successfully released the flamingo which was found a second time in similar condition. This time after rehabilitation, they put a transmitter on the flamingo’s leg and followed its movements for 2+ years until Hurricane Irma knocked out the transmitter’s signal. The whereabouts of the flamingo are unknown and the status of the flamingo as native to the US is pending.

Last story. Last week, a kitten I adopted through a rescue group over the summer was diagnosed with FIP (feline infectious peritonitis), a mutation of feline coronavirus that leads to rapid decline. She is 6 months old and was given a fatal prognosis with an estimate of 9 days to live. A technician using COVID-19 safety protocols, transferred the kitten to me under an outdoor tent. By the time I reached the parking lot, a network of activists and technicians had mobilized around us informing me about an experimental treatment. My messaging apps were chiming, nonstop. This is another page-turner. The network is impressively organized locally and connected globally. It is citizen science and compassion in motion. I am inside of this story. In shock, I am swept up, drawn in. In an exploded view, I stare at the pieces: the ethical dimensions, the politics of global trade, the similarity of drug trials for COVID-19 and feline coronavirus, the passion of the community activist network, how cats came to be human pets, why we intervene in ecosystems, where we draw lines--without judgement, I marvel at the complexity.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |