|

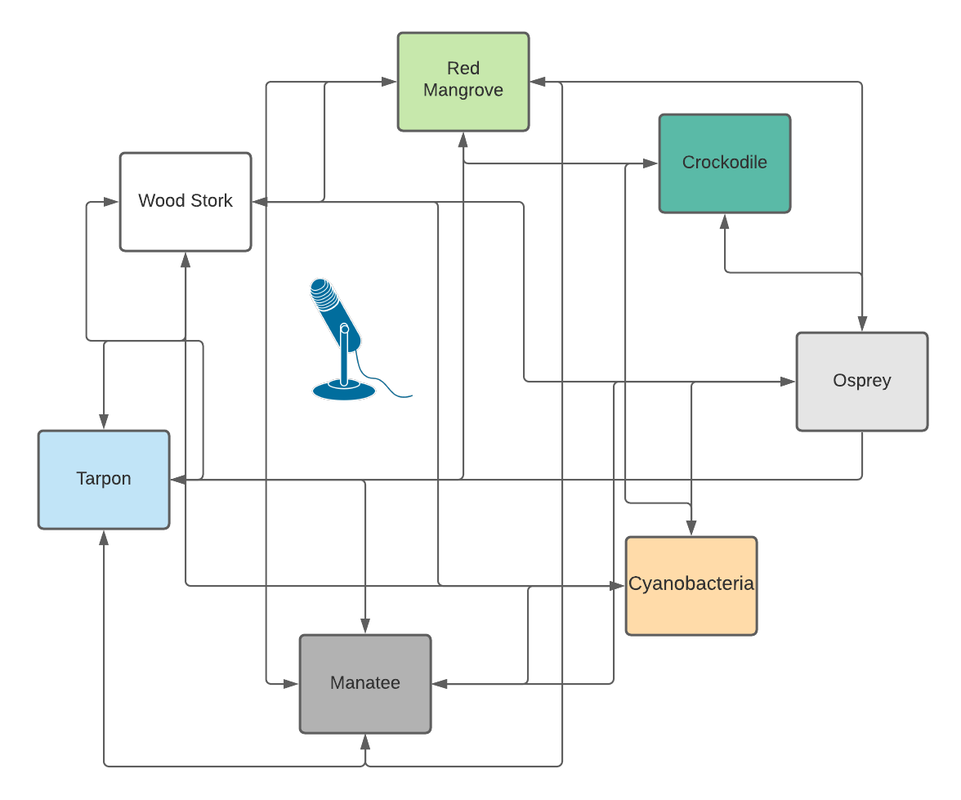

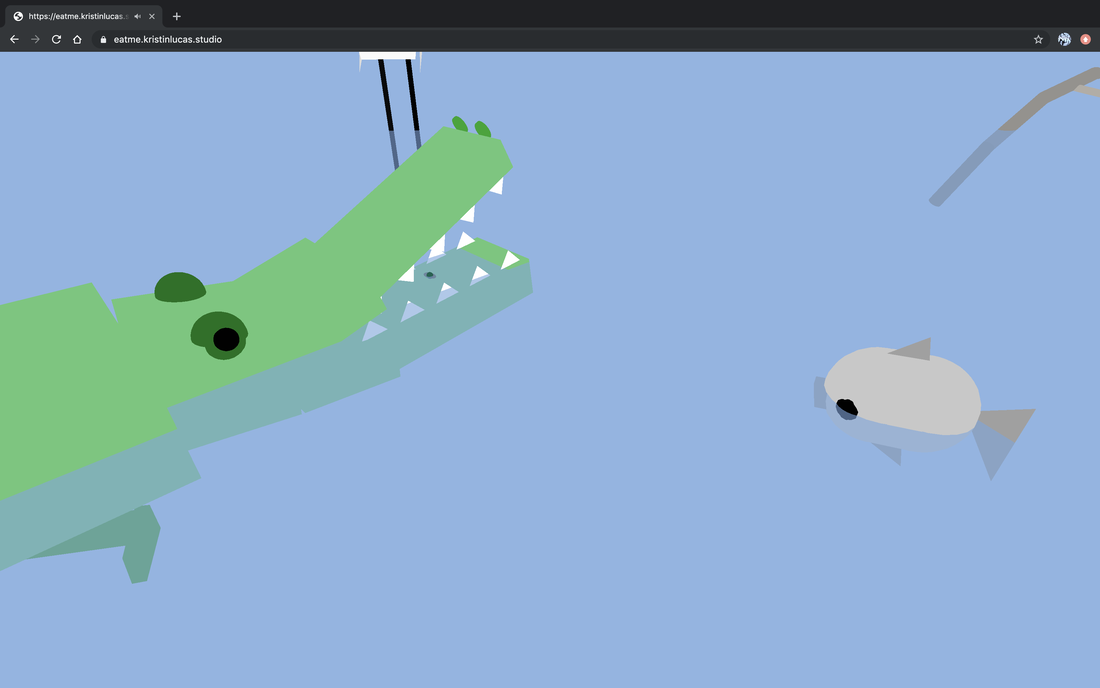

Andy One of the things that Kristin and I have really considered a lot in our conversations has been the art of storytelling, and I think that storytelling does not get enough attention in its importance in science. You often hear about how the stories behind scientific discoveries are more interesting than the science itself, and that’s largely due to the fact that we keep this all separate. And that’s silly. Science, history, culture, and art all fit together tightly, and storytelling is a way to not only advance science, but a way to connect the dots. I have been doing science outreach in some form for 15 years, and one of the most telling activities I ever partook in was the creation of a video series during graduate school. We tried to get researchers to tell stories about themselves in order to humanize the researchers. It didn’t go very well; many of the researchers we talked to were awkward as storytellers and instead wanted outreach to be focused on the discussion of their favorite science. The videos were the most fun when some of the researchers who were able to tell stories, and it was no coincidence that the storytellers having the most fun were also the best at making their science interesting and exciting. We were low on subjects, and so those of us making the films had to turn the cameras on ourselves and start telling our own stories. And in my conversations with Kristin, I started thinking about one I had told. We asked each researcher what was their first science experiment? Most talked about an experiment that they had done at school, but I found that to be a very tricky narrative. If science is a process, then when is the first time you specifically remember going through the process? My first memory of this was back in preschool, and it’s one of my first memories. We had long recesses, and my preschool had a nice space outdoors where we could all play. There was a honeysuckle bush, or at least some shrub with flowers, that always had bumblebees. And I was fascinated the bees, as I still am. They look so happy and fluffy. And I wanted to pet one. I was a kid; things that are fluffy are to be pet. In other words, I had collected observations and formed a hypothesis. The next step was to collect my own data. I followed a particularly large bee, and I tried to pet it with my finger. The data I collected? A stinger in my hand. I cried, and I got more data provided to me from fellow researchers; others had had my idea, and most had been stung or hurt. This changed my views on how to deal with bees, and my new way of dealing with them was to simply leave them alone. And over time, living in this paradigm of not trying to pet bees, I’ve greatly reduced the number of stings. What’s so strange is that I forgot about telling this story for years, but I’ve revived it in the past few years when teaching the scientific method. I’m not saying none of my students roll their eyes when I tell this story, but it clarifies the scientific process for most that I’ve noticed a marked improvement in understanding. Stories and narratives are important for conveying the meaning and implications of science. Plus they’re fun. It’s an art that’s highly underused. And it’s important to integrate them more into both science and sciart. Kristin As an experiment in visualizing what an interactive story about ecosystems might look like, I created a sketch using p5.js, taking inspiration from food web diagrams and national park posters. While Andy continued research on species and ecosystems casting a wide (global) net, I needed a quick sample set to play with and found an opportunity to learn more about species and ecosystems of Texas to build a prototype from. I selected six ecosystems: marsh, river, forest, desert and mountain. In hindsight, I should have included the grassland ecosystem. I selected only twenty species to start with, many but not all of which move between one or more of the selected ecosystems. Next I trained an AI with machine learning technology to look at images of vintage park posters and transfer the aesthetic style of their design onto digital images of Texas ecosystems. I used the resulting images as backgrounds on which to stage the ecosystems. An unexpected outcome is that the color palette shifts generated by the AI algorithm reflect the changing color temperature of light upon landforms at different times of day. To show this effect, I created a few animated GIFs using only a handful of the images generated by the AI. The p5.js prototype I’ve been working on lets you follow a species through ecosystems that it contributes to. Click on the marker for Javelina in the mountain ecosystem and you are transported to the desert ecosystem where you can select a different species to follow, such as the Deer Mouse or Spiny Lizard. A more developed version would include more ecosystems, representation of a greater number of phyla and species, and greater complexity in coding; in addition to color coded silhouettes of species. We envisioned the project (a tool with stories) for an age group that goes birdwatching. That’s something that I want to return to, though I’m excited that the aesthetic approach of this early prototype shows potential as an educational game for kids. Integrating short text-based stories from our research has been another priority for us. In a less illustrative, more functional visual UX design, hovering your cursor over a species map could trigger a popup story about codependent species relationships within a single—or across multiple—ecosystems. Andy had a name for this type of research in the field of biology that I failed to jot down: a bird picks up a fungus on its feet while perching on a tree branch, then flies to another ecosystem and transfers the fungus to a different tree species, linking the two ecosystems in a complex and vital way. Initially, we set out to create a story structure that would support more than one protagonist and that could lead you to something you were not looking for. Such a project could increase awareness of how ecosystems work and demonstrate the range and spatial needs of species, their dependency on biodiversity, and the complexity and interconnectivity within ecosystems.

Throughout our residency, we have discussed the dimensions of human intervention within ecosystems, attempts to restore their balance, the conundrum of restoration to a point in time, the shifting of ecosystems related to warming waters and climate change, as well as markedly-different attitudes toward the same invasive species across different communities/locations, globally. In our final meeting, Andy and I pivoted our project idea into a new form we are both excited about; one that synergizes the mapping of data on species and ecosystem together with data on human attitudes toward species (including invasives) and species’ status in ecosystems (native, introduced, migrating, etc). This new form for our research can highlight the range and spread of species, globally, through a multitude of human resources and perspectives. Moving forward, I’ll be investigating whether this is something we can host on an existing platform as a public research project, or whether it is something better suited to a web app built with a mapping API.

0 Comments

Andy Kristin and I have been working on a lot of concepts in the last few weeks; our collaboration has been really insightful for me. I think that even though I have a foot in the world of science and the world of art, I very much thought that our thought processes were very different, but I feel a strong and true kinship with Kristin, although I do appreciate our differences. There are a few concepts we’re batting around right now, and they involve a few concepts as they gel into a potential project: data, the organisms hidden in plain sight, and storytelling. And so I thought I’d share two things this week. First, yesterday was National Bird Day, so I thought I’d share this picture: My boyfriend and I were walking through a local forest preserve (Which one? Don’t worry about it. Great Horned Owls are territorial and mate for life. The owls we saw are likely staying put for the winter, and I want people to leave them alone), and we spotted two Great Horned Owls. We were wandering along a path, and I noticed a number of droppings on the path and decided to look up. And there was an annoyingly loud little hairless ape wandering along pestering his boyfriend, and so one of the owls peered out and looked down. And we stared at each other for a while. Great Horned Owls are the largest owls in Illinois, and they can be found throughout the Americas. They are of the genus Bubo, which I find to be an adorable name, and hunt mainly rodents. We saw two Red Tailed Hawks in a prairie on the way into the forest, and the two species are very similar, only one is diurnal and one is nocturnal. Great Horned Owls are not endangered or even vulnerable; the IUCN has stated that is of the least concern. I asked a bunch of friends if they’ve seen a Great Horned Owl. I was so excited to see it that I may have told way too many people about it in the last few days. Only a handful had ever seen a Great Horned Owl, let a lone an owl in general. And this is a large bird; one of the largest in our area. In my discussions with friends, I kept thinking about conversations I’ve had with Kristin; how many species are around us that we have no idea are there and that we are unaware of. Sometimes, they’re too small. Sometimes, they are too well camouflaged. Sometimes they just are only out in the evening and nights, and it’s really cold at night these days. We’re so often unaware of the world around us, but it has so many wonders to give us. My boyfriend keeps making fun of me for how excited I got seeing the owls. Did I mention that I saw two Great Horned Owls? Less than 10 miles from my home! I’m still happy as a clam about that. I wonder how many clam species were in the North Branch of the Chicago River that my boyfriend and I walked over as we made our way into the woods. The second thing I want to talk about was the monarch butterfly. As Kristin and I are doing research around the world, I stumbled upon a fact that absolutely shocked me. I’m well aware that the western monarch butterfly, one of many populations of migratory members of the species are disappearing and threatened. It’s largely loss of overwintering sites along the West Coast and in Mexico. I love the monarch. I like seeing them in Chicago and throughout the state of Illinois. Monarchs are our state insect. But I didn’t know they live in Australia. Milkweeds and other plants were introduced around the world accidentally and as ornamental plants as soon as Europeans started making their way around the world. In the late 1800’s, people released monarch butterflies in Australia, potentially to eat the invasive milkweeds, but it’s likely that they had already made their way to this part of the world. I wanted to just bring up how strange it is to think of this beautiful butterfly that I constantly worry about being endangered as an invasive species. They aren’t alone. Many species are thriving as invasive species and hurting in their native range. What organisms are supposed to be where they are? And what species are around us that we don’t even know about? Things I keep thinking about. Kristin The world is an oyster and you go down a rabbit hole. Andy and I set out to research pairs of species with codependent relationships at specific times of year. Species movement could lead us from one ecosystem to another where we could find new codependent pairings. I was eager to dive into this research but like the White (East Siberian) Wagtail that wintered in Austin last year and drew thousands of bird watchers from around the country to a small neighborhood park, my research journey took me off course and down multiple rabbit holes. To the backdrop of unprecedented changes to climate and migration, questions have been forming around how I want to use data. How reliable are existing data sets for the purpose of this project with ecosystems shifting as they are today. Over the past few years I have been gradually letting go of expectations that species I am familiar with will be reliably present in locations where I have previously encountered them.

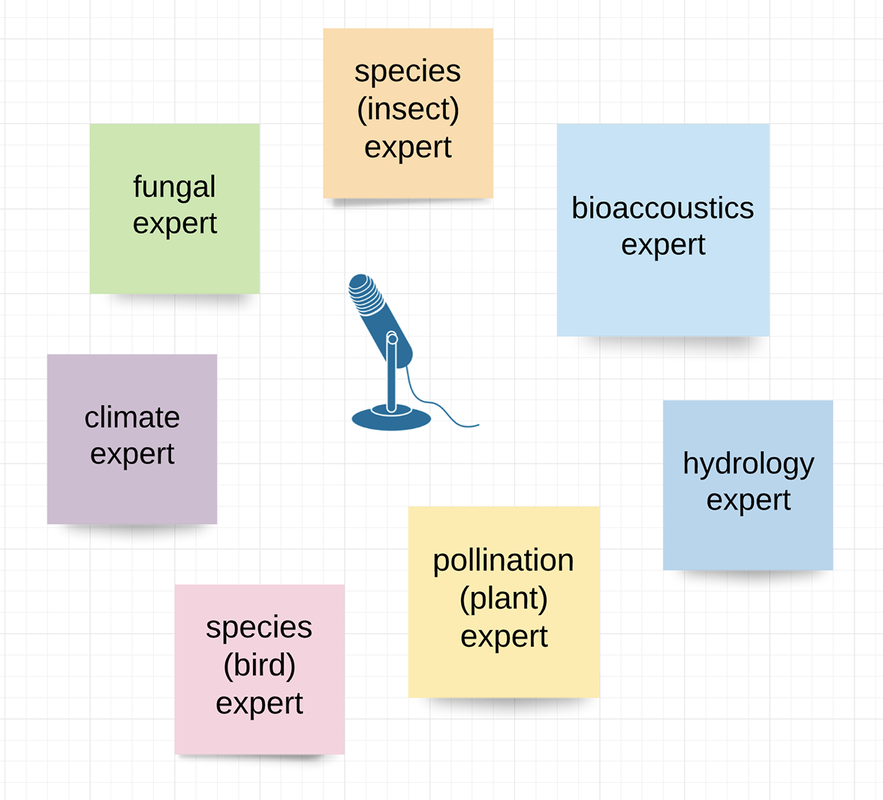

I started with my yard: Cats and Geckos. Feral cats reproduce multiple times a year in my neighborhood which is situated near a greenway, park, river and a migratory flyway. They are a menace to the birds but close relationship with a feral queen led to an interesting observation; cats eat House Geckos and Mediterranean Geckos—introduced invasive species in Texas—and Geckos carry liver flukes that can become fatal to cats if they get lodged in their bile duct. Mama hunts geckos all day long. The cats stay close to home and the geckos stick to the urban environment. I couldn’t find a clear path out of Austin. The Cedar Waxwings have returned. I know where to find them but I don’t know anything about the trees they perch on or the role they play in my local ecosystem. Why are they in Austin—now? Through internet resources, I learned the waxwings are here to forage on berry-fruit bearing trees, such as the Ashe Juniper, Hackberry and Yaupon Holly. I have berries in my yard but they are none of the above. I have three trees in my yard producing berries but their leaves have smooth edges, ruling these species out, and in fact I have not seen a bird within ten feet of them. The Yaupon Holly happens to be the only naturally caffeinated plant species in North America and it is native to Central Texas and a couple of other Southern states. Yaupon leaves were brewed by indigenous peoples to create a ritual drink that is likened to Yerba Mate. But the hot spots for waxwings are the upper branches of tall trees that have shed their leaves. I don’t see any berries through my binoculars. I presume this tree species is dependent on species like Cedar Waxwings and Eastern Bluebirds who pass berry seeds through their digestive system, propagating the species by dispersing seeds to other areas they move between. I have only seen blue-berries in Austin. Kristin In absence of a tree to climb, my trunk is a suitable stand-in for the five kittens I am raising collaboratively with a feral queen. I bear the marks of a feral cat network hazing ritual on my body, and as I type my hands ache from their fierce yet intimate bites and scratches. Every day, it’s homeschool. By dropping any pretense of foreknowledge over the past 18 weeks, I have unlearned what I thought I knew about cats and interspecies communication. I recently returned to the story of Mary Howe Lovatt, a naturalist who participated in a 1964 NASA-funded research project on dolphin intelligence. She proposed and carried out living with a dolphin named Peter in a hybrid salt water office environment for a period of ten weeks during which time she attempted to teach the dolphin to understand and speak human language. Her inspiration for the experiment was a story about a cat that communicated with humans. This week, as Jupiter and Saturn came into alignment for the first time in nearly twenty years, closer to home an inevitable dilemma comes into focus: what to do with the kittens. In all fairness they need more space that I can provide for them without building infrastructure. I’d like to reintroduce them to the feral community after their surgeries but I resolve to say that the ecosystem in my neighborhood is heavily lopsided toward humans and cats. Releasing these stealth kittens back into the yard will increase the vulnerability of birds and Austin is situated along a flythrough that at its peak brings over a billion birds through the city. Ferals are also a nuisance species for some. This week Animal Control is thought to have scooped up my next door neighbor’s indoor/outdoor eight month old kittens. Let’s say you want to create a story about an ecosystem. How do you tell a story without a protagonist? Andy and I circle back to this in our meetings. While I have been mining hyperlocal ecosystems and experts for inspiration, Andy has been diving into global biodiversity datasets for a deeper and wider view that has been fruitful for finding perplexing stories about human intervention and unexpected attitudes toward invasives. We’ve settled on a framework for our collaboration, we’re setting out to do some research over the next two weeks, and soon we’ll be finding and the next step will be finding its form. Sketches for podcast idea to generate new stories about ecosystems Like all species, we are bound by a unique set of sensory, motor and cognitive systems that shape our perception of the world. We experience the world from where we stand but we lack the ability to see how ecological events are connected, especially across great distances. Equally, we cannot see our own impact on the world. Andy and I have settled on a framework for our collaboration. We have a research goal for the next two weeks, and then we’ll decide on our project’s form.

Andy Kristin and I met briefly this week and had a quick discussion before realizing that we needed to move things back a little bit. The end of the semester is harsh for those of us trying to teach remotely; the challenge of trying to maintain rigor and connection during this semester have been immense, and that’s before you add in the other, less considered aspects of the job. But there are a few things I’d like to point out this week as I plot through grading final projects and reaching out to some wayward students who have really struggled to keep up in trying times.  First, my nonprofit has been posting a lot on twitter this week about fluorescence and giardiniera. Giardiniera is an amazing condiment that, in spite of my Italian ancestry, I was only introduced to when I moved to Chicago 14 years ago (I just celebrated my Chicago anniversary!). I will fess up to the fact that all the posts are coming from me. I recently bought myself a black light flashlight in search of all things fluorescent after the news of 3 mammals being shown to be fluorescent in the last few months, flying squirrels, platypuses, and the Tasmanian devil. Fluorescence is an apparently more-common-than-we-thought characteristic of certain compounds that will absorb light as almost all objects with coloration will do, but instead of simply allowing that light to dissipate as heat or vibrations (Like a blacktop parking lot), fluorescent compounds will release most of that energy as a slightly lower energy light. I’m carrying around my blacklight in hopes of discovering something new or exciting that is fluorescence. Long story short, I rediscovered that all vegetable oils have a fluorescent and appear red under a black light. This is because of chlorophyll that remains in the vegetable oil. Two reasons I bring this up: 1) Much like doing art, doing small, simple science experiments can fill your life with wonder and awe. There’s so much around us that we don’t explore, and it’s full of fun mysteries and excitement. 2) Do your research. Everyone already knew this. No credit for rediscovering the wheel! If data exists, use it! Secondly, I’ve been thinking a lot about something Kristin and I were talking about, about the world we pass by everyday that’s unseen and hidden in data. One thing that sprung to mind and I mentioned to Kristin immediately was our microbiomes. Every one of us has thousands of species of bacteria, archaea, protozoa, and fungi living in and on us. The microbiome is well documented, and each of us have a unique microbiome in every crook and corner of our bodies. On the tip of our noses? Unique microbiome. Not just compared to the rest of our bodies but compared to everyone else’s bodies. The fold of our noses? Completely different microbiome, with different microbes living, surviving, and thriving. Our microbiomes are not just all tiny microbes, but it’s estimated we even have tiny animals crawling all over our skin and face at any given time. Sorry. Usually I warn my students about that one before bombarding them with that fact. But this isn’t exactly what I was thinking about with Kristin. We know a lot about the human microbiome. Or at least, we know more than for almost any other organism. But what of those different organisms? What’s the microbiome look like on a maple tree, like the red maple (Acer rubrum) outside my window. What bacteria and fungi are living on that tree? And more specifically, what’s growing where? What’s on their stems, on their leaves, on their new buds, on the trunks, on their roots, etc.? And hopefully everyone isn’t raking up their leaves in the fall and removing them, because that means that you’re removing important nutrients and destroying an important biome. There’s too much information about different biomes out there for me to share everything, but please consider that while you might be eating yoghurt to help with a bum-tum or using different face washes to avoid acne, these very different biomes are not unique to the human body; there are hidden ecosystems on almost every organism we can see with our naked eyes. Andy One of the things that Kristin and I are both really fascinated by is the things that people are not seeing. Kristin and I had a great conversation about all the data that can be collected from the world around us and all the life forms we can’t see. I’m a microbiologist by training, so I’m constantly worried about things just outside of the scale of our perception, but our conversation concerned more the movements, the comings and going, and the migrations of organisms we can perceive, but simply are like two ships in the night. We don’t see because they are just out of eyesight, or that we miss seeing by only a few minutes, or that we just didn’t know how to look for. Every year thousands of birds fly from their winters in the Caribbean or elsewhere in the tropics fly north along the Mississippi and pass through Chicago on their way further north, towards the conifer forests of the Upper Midwest, Great Lakes, and Canada. I know during the spring and the fall that these birds are flying by my apartment; I pay attention online for sightings of palm warblers and chestnut-sided warblers, and while I don’t see them every year, I know they’re less than a mile from me a few weeks of the year. This got me thinking of a research paper I absolutely love. The paper asks the question: what’s living in the subways of New York City? The answer: A lot! And what was there was fascinating. Researchers swabbed and collected genetic information from every subway stop in New York City, as well as collecting data from a few other select sites like the Gowanus Canal. What they found was fascinating. First, there’s a lot of bacterial species around you at all times in the subways, a huge fraction of which we have no idea what they are. It’s strange to think about all the things we interact with on an everyday basis that we don’t know that we’re interacting with, but adding on that we don’t know what they are adds another level. Even the things we do know, like DNA found that closely resembled the Mountain Pine Beetle, just tells us about how much we still don’t know (The Mountain Pine Beetle was listed in genomic data bases at the time, but related species, cockroaches, were not). What further fascinates me about this paper is what people were unaware of that were potentially dangerous. When grown in a lab on plates full of antibiotics, many bacteria continued to grow. Many sites had bacteria resistant to drugs used to fight infections and diseases, and they were on the surfaces all around busy MTA riders. There are two more things that are worth pointing out. One is one of the many authors of this paper. Ellen Jorgensen is a respected molecular biologist with a number of impressive roles, but in this paper her affiliation is listed as Genspace. Genspace is a community biology lab in New York City that I mentioned in an earlier post. While Dr. Jorgensen is a trained scientist, citizen science played a key role in this paper. The other thing that is worth stressing that brings me back to my conversation with Kristin is the vast amount of data in this paper. Each of the six figures in this paper (And the twelve supplemental figures and seven supplemental tables) are jam packed with data. Data on sequences. Data on growth of bacteria in the presence of antibiotics. Data on methodology. There’s enough to look at here to keep you busy for a couple of days. And this is a snapshot for a few specific sites in New York City, not through investigations of the entire ecosystem or even every part of the subway system. My students often ask if we could collect this data on the L here in Chicago, and yeah, we could. We’d have to collect a few partners from a few labs with better equipment than I have access to, but we could definitely get these data. The data are out there waiting for us to collect them. And that data can be absolutely fascinating. Kristin In fields of science and art, what’s exciting is to discover what you are not looking for! Hold space for this thought. For now, it’s our north star. Andy and I have a mutual fascination with the complexity of ecosystems and a shared concern about how ecosystems are shifting as a result of climate change. Icon, a Megellanic penguin I sponsor near the Strait of Magellan, has been rearing chicks. Warming waters and rising temperatures have pushed species out of range and Icon must travel farther than ever to find a food source. At the nesting site, scientists are documenting a loss of body mass among breeding Magellanic penguins. Reports of declining bird populations make frontpage news these days but impacts on critical life forms that we cannot see, such as bacteria and fungi, are under documented and under reported. To understand impacts on and relationships within an ecosystem, you need data over time, so today Andy and I began exploring publicly available biodiversity datasets. These datasets are impressive yet they can be overwhelming in amount. We have arrived at an idea to explore and over the next two weeks we will play around with what that might look like. Here is a sketch of a related project that I plan to launch in spring of 2021. It’s a project that I began working on almost a year ago and that has been on pause for the past six months due to the pandemic. It has been generative for framing questions, concerns and pitfalls about working on a hybrid project that falls somewhere between art and science.

Andy I’m going to write a relatively short post today. No one has ever said that brevity is my strong suit, but every once and a while I try. Kristen and I had a really lovely conversation today about the potential beauty of data. Data is the bread and butter of science. When you conduct an experiment, you gather data and see if that data supports your hypothesis. Data can be analyzed in different ways to yield various insights, but the inarguable information should provide indications of correlation, anticorrelation, and the lack of any correlation at all. The end of a great experiment, for most researchers, is a bunch of data, and that data, while often only a bunch of numbers, can lead to new clarity on all matters of things. But what often scares away potential scientists? Data. Numbers. Math. Complexity. I often ask my students in biology courses I teach why they chose to take my course. Every semester I’ve taught at my current institution, at least one student states that the life sciences seem to house the courses that have the least math and the courses that they won’t have to work with large data sets. I’m not sure the reason for this dislike of numbers, but it may spring from the idea that beauty, life, and truth is qualitative, not quantitative, and that any numeric evaluation of these concepts seems reductive and wrong. If each data point can be represented by a series of numeric values, the world seems cold and detached. But that’s not the only way to see this situation. Data shades in more details and character to any timepoint, individual, or outcome. Do you want to tell a good story? Collect more data. One way to get a good story out of data sets is by creating a simulation. Simulations are usually computer programs where we can train said program using a data set. This means that within the data we have, we can figure out the odds and chances that certain outcomes happen if we see certain phenomenon. For instance, if someone were observing me, every time they saw me enter a room with bananas, granola bars, and cookies, data in the subsequent few seconds will see the number of cookies in the room fall at a very predictable rate. If we built some simulation with me wandering around Chicago, we can predict the rate at which different foods (cookies) will disappear. One of my favorite stories from a few years ago came out of Aragonne National Labs outside of Chicago. Researchers there simulated a zombie apocalypse. The report was very tongue-in-cheek, but the information gained was still useful. Now, we don’t have data for a zombie apocalypse in order to build said model, but they used data from transmission of MRSA, an antibiotic resistant bacterial infection. Using that data, they learned how quickly a pandemic could cripple a city like Chicago (We’ve recently confirmed that). Was the data we gained from this simulation really meaningful for the current pandemic? Yes and no. This simulation was built using data from the spread of a bacterial disease, and that differed from the transmission rates and methods of our current pandemic, but there are a lot of interesting results, including that certain locations like the Cook County Jail could be a hub of disease transmission. As I’ve said, this simulation differed greatly from our current pandemic, but the data potentially was pointing us towards some uncomfortable truths. Data is nothing to be scared of. Data is not something that detracts from a story, but something that can add to it. Data can be used to create impressive narratives and spooky tales, like that of a zombie filled Chicago. Look, we can prove this: Chicago is great. No zombies to be found: That said, we do have a pandemic raging here. Please make sure you’re keeping your neighbors, friends, and family safe. Maintain social distance, wash your hands regularly and for 30 seconds with soap, keep wearing your masks, limit face-to-face encounters (Especially indoors). Kristin

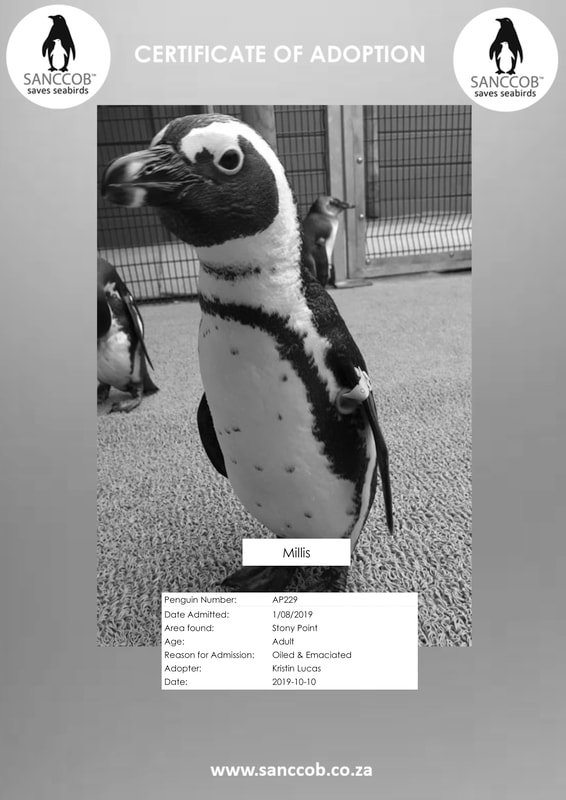

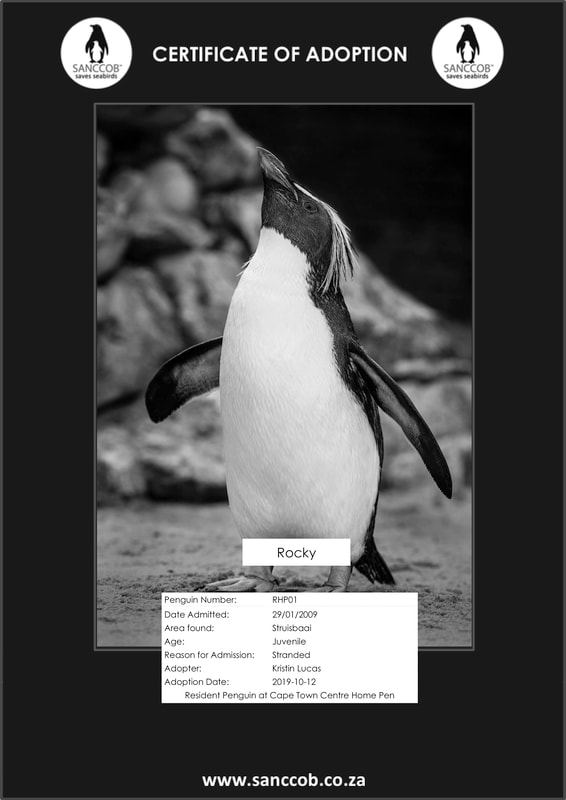

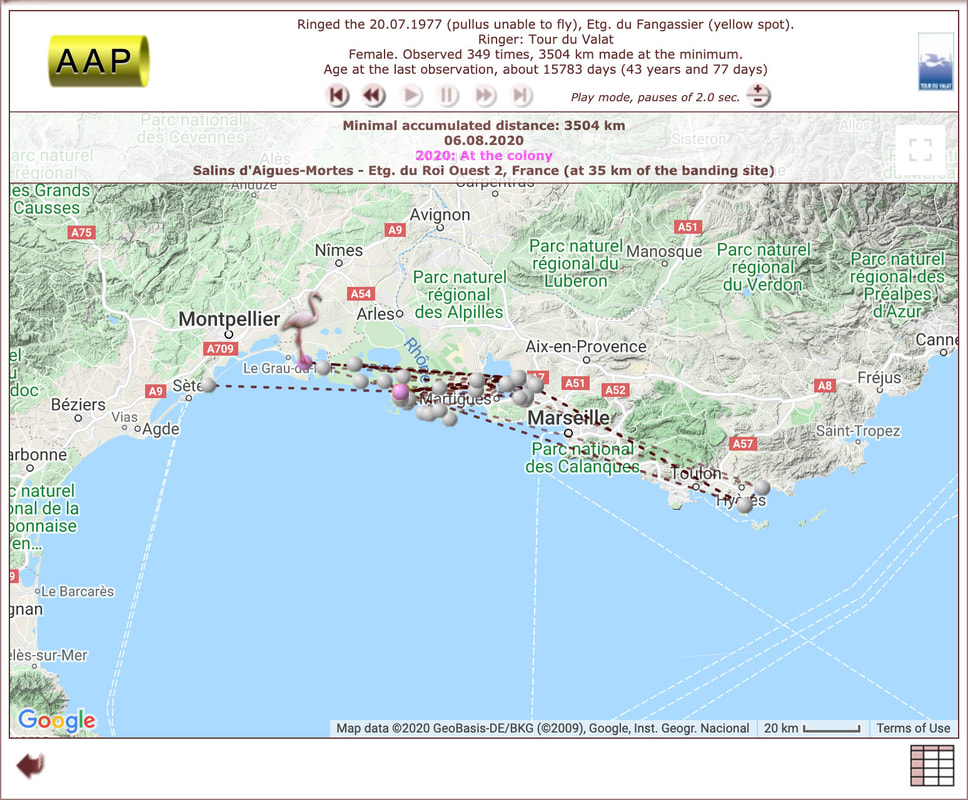

Since my last blog post, I joined an XR for Impact incubator organized by StoriesXFuture and Andy generously helped me narrow my ideas for the incubator down to just one. A pattern I fall into is splintering ideas into endless iterations--all of which I am passionate about but for practical reasons, most projects end up on the cutting room floor. During our visit, I witnessed Andy’s creative problem solving skills in action and grew intrigued by his deep knowledge of Chicago’s history and ecosystems. New pathways for moving forward in our collaboration began to open! By the second session of the incubator, I pivoted my idea. Not because I had arrived with a bad idea but rather because it was not the best fit for my growth. Instead I will embrace the challenge of creating an idea with greater potential for impact based on insights gained through the incubator’s workshops, such as Design for Impact led by Chicago designer George Aye of Greater Good Studio. Within the incubator community, I connected with a representative of Global Earth Observation Systems (GEO) and I am exploring ways to build a project that utilizes biodiversity and climate change data gathered from satellites, a less burdensome form of animal tracking than using physical trackers. The incubator runs through November 24 so I have some time to land my new idea. Unlike the high-end production values of NatGeo (wildlife photography and immersive 360 video) and Disney productions, both for which research has proven their effectiveness at increasing empathy in the viewer, my productions are usually low budget with crudely-rendered cartoonish characters. They are not terribly successful at immersion but they are playful in how they use technology to frame the complexities of people’s relationships to land and animals and to engage audiences, socially. My productions have been difficult to fund yet are fun and memorable to engage with. A positive outcome of my work is that it provides comic relief from the intensity and emotional labor of processing climate change impacts and declining biodiversity and habitats. I’d like to transition from creating calls to action that require donations from Mom & Pop to finding support from foundations, investors and corporations as a way to scale projects to be more impactful. My projects are built upon scientific research, data and journalism yet the impact of my work has been difficult to measure. Impact registers internally, emotionally, and philosophically, if at all. This week, I am weighing how best to channel my creative efforts and instrumentalize new partnerships to increase the impact potential of my work. As an artist coming of age during the shift from analog to digital (one-way communication to participatory media) and engaged with cable access television and the early Web - DIY, make-do, and amateurist approaches to media resonated with me. They promoted participation and accessibility while letting you in on the process of making. A similar potential attracts me to citizen science: the idea of empowering communities, opening up pathways to agency, and redistributing power for mutual benefit and wellness. Andy I have to say that I’m really enjoying meeting with Kristin, but I want to explain something our conversations have highlighted and that probably makes my journal entries on here seem a little bit off. I’ve introduced myself in my first blog post, but it’s likely you’ve noticed that I’ve not talked about a lot of specific pieces I’ve done or research that I’m currently doing, and I should probably explain a bit. In 2016, I transitioned from traditional research to working at primarily undergraduate research institutions as a professor, focusing on teaching and largely giving up the research component of my professional practice. It’s also around the time I started making my third attempt at creating a public biology lab in the great city of Chicago, and I feel like that has not in any way diminished my interest in leading and exploring personal projects, but it has caused me to put them on hold while focusing on building my community. In the end, I want to participate meaningful citizen science projects as part of a community lab, and community lab projects are going to come from a community. I see myself as a facilitator and a researcher for those projects, but the single principal investigator model is not something that works for community science. I really wanted to dive into the concept of community biology labs to explain a bit of my background coming to the Bridge Residency. Biotechnology is just like any other in many ways, and if there’s technology for people to explore in a professional setting, at some point, that technology is going to start to get into the hands of amateurs and enthusiasts. I can’t tell you the first time this first happened, because I’m willing to bet that as soon as ancient civilizations started brewing beer in China and the Middle east, people started playing around with yeasts and bacteria to make their own private residences, manipulating and culturing strains at home to create the ultimate party brew. As soon as people started to have livestock and pets, individuals started breeding them to fit their tastes and desires. However, the DIY (Do It Yourself) Bio movement as it’s understood today started gaining steam in the 1980’s. People started doing research and individual projects at home and contributing to science in general and to a dedicated global community of hobbyists, enthusiasts, and entrepreneurs. In 2010, the first public biology lab in the United States was founded in New York City and named Genspace. Organizers started meeting in basements and apartments doing small, simple experiments on communal equipment, and slowly morphing into a lab where anyone, after providing a small membership fee and taking some basic training, could start to get their hands wet experimenting with biotechnology and biology in a supervised and safe environment. Later that year on the end of our great country, Biocurious started in the San Francisco bay area. This has been followed by a number of spaces that have established long running communities of citizens generating interesting projects, communicating back and forth with experts, and contributing to meaningful science. Some of the labs that have inspired me include BUGSS in Baltimore, Counter Culture Labs in Oakland, and countless others both in the United States and around the world. In 2011, I was lucky enough to attend a conference where Ellen Jorgensen, one of the founders of Genspace, was giving a talk. I highly recommend listening to Ellen talk about the power of community laboratories, because maybe it will inspire you as much as it inspired me. These spaces have such potential in allowing people to play with and learn about biology while at the same time expanding business opportunities and encouraging exploration. The coasts are well populated with community spaces where people can tinker and explore with biology, but the Midwest is a desert. We want a space for everyone in Chicago to try their hand at playing around with biotechnology. My lab is called ChiTownBio. I’ve been setting it up slowly and carefully with a dedicated team of friends and colleagues, and we hope to set up a space during the pandemic that we can slowly and safely open as we get more control over the pandemic as a society. We want to encourage. This project has effectively destroyed my ego; we want this space to be doing the science dictated to us by our neighbors and fellow citizen scientists, and my interests have been put on hold until we can create a space for everyone first and foremost. But that doesn’t mean I don’t have dreams of my own projects in the future. They’re just temporarily on hold till our community can flourish and sustain itself without supervision and guidance. Then it will be time for me to launch some of my own citizen science projects. One of the reasons I wanted to do this residency is that community laboratories can become spaces for inspiration and exploration for bioartists and biodesigners. I am in love with biaort and biodesign, and have a few projects I really want to explore, but I wanted to learn how to interact and work with artists in a meaningful way, but I’m learning my desire to simply be an enabler and facilitator is different than being a collaborator, and so I’m really looking to shift focus to be a true partner for Kristin, whose work is exciting and inspiring to me. This is where I’m at right now: diving in headfirst to true collaboration and allowing my interests and passions to help steer a hopefully meaningful project. Kristin Animals & The Internet: Short Stories This summer while sheltering-at-home like most everyone else in the world, I excitedly tuned in for a webinar by SANCCOB, a foundation in South Africa for the conservation of seabirds. Their team rehabilitates seabirds and in most cases, they successfully released them back into the wild. I sponsor Millis, an endangered African penguin; and Rocky, a Northern Rockhopper penguin who is unable to return to its colony. Mid-way through an informative slideshow featuring fuzzy hatchlings and juveniles, I become aware of COVID-19 impacts on the team’s work. Penguins are afflicted by a fungal disease that has been successfully treated with the now infamous anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine but it has been completely sold out from regional suppliers and shipped overseas. Factoid: I sponsor 24 seabirds and 1 chimpanzee through the Internet and I currently have 9 cats in my living space. Initially, I adopted flamingos from the South of France because of the novelty of the online transaction and the uniqueness of the offer. I could follow their movements through an online research platform. Eventually, I flew to France to assist with the banding of newborn flamingos. This month, I received an email update that the eldest flamingo I sponsor (born 1977; now 43 years old), has been sighted again with its colony, near her birthplace. The story of the status of the flamingo in South Florida is a page-turner. It is multi-faceted and complex. For now, I will give you a glimpse. Back in 2018, I met with a team of conservation scientists at Zoo Miami who told me the story of receiving a concerned call and rescuing an emaciated flamingo. They rehabilitated and successfully released the flamingo which was found a second time in similar condition. This time after rehabilitation, they put a transmitter on the flamingo’s leg and followed its movements for 2+ years until Hurricane Irma knocked out the transmitter’s signal. The whereabouts of the flamingo are unknown and the status of the flamingo as native to the US is pending.

Last story. Last week, a kitten I adopted through a rescue group over the summer was diagnosed with FIP (feline infectious peritonitis), a mutation of feline coronavirus that leads to rapid decline. She is 6 months old and was given a fatal prognosis with an estimate of 9 days to live. A technician using COVID-19 safety protocols, transferred the kitten to me under an outdoor tent. By the time I reached the parking lot, a network of activists and technicians had mobilized around us informing me about an experimental treatment. My messaging apps were chiming, nonstop. This is another page-turner. The network is impressively organized locally and connected globally. It is citizen science and compassion in motion. I am inside of this story. In shock, I am swept up, drawn in. In an exploded view, I stare at the pieces: the ethical dimensions, the politics of global trade, the similarity of drug trials for COVID-19 and feline coronavirus, the passion of the community activist network, how cats came to be human pets, why we intervene in ecosystems, where we draw lines--without judgement, I marvel at the complexity. Andy

One of the really great things about this fellowship is being able to sit down and talk over Zoom with Kristin. Kristin is a really impressive artist. If you haven’t sat down and really looked at all the videos and documentation of her projects on flamingos, I recommend doing so as soon as you have the chance (This video’s my favorite). It’s a really fun and fascinating project that blends interactivity, science, nature, culture, and a call for action. We’ve had three meetings so far where we’ve been able to meet virtually, and I’m so grateful to be paired with her based on our conversation so far. One thing we’ve stumbled upon is that we both are have committed much of our headspace to similar concepts. Everyone is part of this fellowship because we want to blend science and art meaningfully, but there’s a shared interest in narratives, cultural implications, and the boundaries and limitations people put on science and art. One thing that’s come up multiple times is the idea of interactivity. I’m a scientist at heart, and even when I am exploring the role of an artist or a designer, I want to communicate my love and awe of the human quest to understand the workings of the universe and the desire to use that understanding to improve our shared existence. To convey that affinity, that wonderment, and that deep appreciation, I find it hard to not be most moved by art that asks those who experience it to take on the role of an experimentalist or theoretician. Art and design have the ability to decontextualize the process by which we learn about what science is. But if we go by the cliché science idiom that, “Science is a process”, then sci-art needs to be allowing people to experience that process in a meaningful, engaging, and impactful way. Why not combine this artistic and philosophical exploration of the world around us with play, with tinkering, with problem solving? Try as I might to convince friends that Harry Nilsson’s "Think About Your Troubles" is a meaningful discussion of biogeochemical cycling, I’ve yet to meet anyone who interprets the song as an exploration of the hydrological and carbon cycles. Art that asks its patrons to really roll up their sleeves and dig in on exploring concepts, learning them as they move in an unfamiliar landscape with new constraints and laws of existence are pieces that tend to blow me away. It may be why I’m so drawn to Kristin’s pieces I’ve linked above. So let me share a few pieces that I think really typify this power of interactive art. One of my favorite pieces to share with my students is Heather Barnett’s Being Slime Mold. The piece is essentially asking participants to do a bit of improv, but the role they always are playing is that of a nucleus in a species of slime mold called Physarum polycephalum. P polycephalum has two bizarre abilities: 1) It can fuse many cells so that many nuclei can occupy the inside of a super cell. 2) The slime mold has the ability to learn and to make decisions. It has a sort of intelligence we don’t understand, and one that doesn’t rely on words or images, but instead a type of rhythmic pulsing. In the piece, participants are asked to link hands and navigate collectively as the nuclei within a slime mold do, expanding and contracting as they navigate through space, finding treats and traps along the way. According to Barnett, the experience led participants to engage with what we know about slime mold in a playful and experiential ways and to have insightful conversations on biology and emotions. I love that this is a group experience, and that it highlights learning as a philosophical pursuit. I don’t think I’ve ever been asked to think like a slime mold. I’m up for that challenge. Another project I absolutely love is sponsored by ASM, the American Society for Microbiology. Every year, they have an Agar Art Contest (the deadline for this year is fast approaching!). This may seem simple enough; you use microbes to paint. This is a project I have my bioart student do early in the semester. Bacteria, fungi, and protozoa provide the pigments and artists, often scientists, children, or makers, simply arrange the microbes to create pleasing images and aesthetics. But there’s something delightfully more complex here. When I first do this with my students, I provide 3 strains of bacteria: E. coli that will grow into white blobs (Colonies), E. coli expressing GFP (Making a protein called Green Fluorescent Protein that will make them appear green and glow under a black light) that will grow into green blobs, and E. coli expressing RFP (Red Fluorescent Protein) that will form red blobs. Students who enjoy this and want to explore further have to explore further on their own, learning how to induce novel protein expression from foreign DNA they trick E. coli into absorbing form their environment or growing different bacterial strains and species that will produce different pigments, patterns, or textures when growing. It’s all a trap into learning a lot of basic microbiology techniques, but by means of creating something that doesn’t feel bookish or academic. It’s a form of learning by doing, but learning microbiology by doing painting. Or maybe learning painting by doing microbiology? The reason I bring this up is also to really articulate a concern I have for the coming months and that will likely have to be addressed and identified in the coming months. If the art I want to create and collaborate on is something that forces the participant to take on new roles, to interact with the science, and to experience living things and life science techniques, how do we do that during the pandemic? How do we interact with the people and the world around us when people are forced to be distant and so much of the world around us feels very far away right now? And so that’s where I am in this fellowship, contemplating how to make interactive experiences while we’re all so socially distant.

Andy

Hello Reader. My name is Andy. You could call me Dr. Andrew Scarpelli, but if you did, it would take a few seconds for me to register. I feel more comfortable as Andy. Dr. Scarpelli feels a bit stodgy. I think a lot of scientists feel that way. As you can tell from my rarely used honorific, I have spent a lot of time studying and working in microbiology and molecular biology. I identify strongly as a scientist. Science is a lot of different things to different people. Students may have to memorize that it’s a process, but in my mind it’s also a worldview, a conversation, a religion, a coping mechanism, and context for the world around us. But it’s also a bit misleading for me to identify solely as a scientist. While attaining my Ph, one of my thesis committee members complained that my projects seemed to be too much engineering and not enough science. If science is gaining insight into how the world works, engineering is applying that insight to build something novel and utilitarian. Since graduating, I’ve steered far from a traditional research lab, instead focusing on science education as a college professor, and I’ve somehow unbeknownst to me been given the amazing opportunity of working at a prestigious art school teaching about bioart. I love the job and revel in it, but I’ve had students complain that my focus is often too much design and not enough art. If art is creating aesthetics to question, critique, and emote, design is applying those questions, critiques, and emotions to build something novel and utilitarian. Concurrently, I’ve been working with a rag-tag group of science professionals, hobbyists, and biology enthusiasts to build ChiTownBio, a public biology lab in the city of Chicago. ChiTownBio plans to be a space for everyday citizens to try their hand at creating, building, exploring, and experimenting with biotechnology under the supervision of trained professionals. We are creating a community of amateur scientists to try to democratize biology, to empower those outside of the ivory towers have stronger voices in the direction of future biotechnology headed. So it is with this conglomeration of identities that I enter this residency. I’m an institutionally trained molecular biologist trying to encourage a community of biohackers, biotinkerers, and DIY biologists to forgo the need for rigid institutions. I’m a scientist who is often more excited to be engineering solutions than exploring the unknown. I’m a bioartist and biodesigner with little experience in either art or design and some confusion about the boundary between the two. And I suspect that these qualities are not unique. Over the last few decades, the concept of multidisciplinary collaboration has come in vogue in many academic circles, but it is likely that just as some projects can have multiple, diverse invested parties, I think individual parties often become invested in multiple, diverse projects. I’m so excited to be working with Kristin as I explore this new space. As can probably be seen in the rambling you’ve nearly finished. I have so many questions and interests to explore. How can we contribute to the expansion of scientific knowledge, engineer useful systems, contribute to the dialog in art and design, participate meaningfully in science communication, and encourage universal participation in shaping biotechnologies? Is there a way to combine traditional science, engineering, art, design, communication, and citizen science in an impactful way? To end this rant, I want to make sure that I provide some aesthetics from my own work, some organisms I’ve grown and observed for you to look over and contemplate. One is an image of magnified bacterial colonies of two different strains of E. coli expressing different fluorescent proteins. One is the fruiting bodies of lichens seen through a dissecting microscope. The last is a plate of Physarum polycelphalum growing to the size that it attempts to escape the petri dish I just grew it in.

Kristin

Hello community! I am super excited to kick-off this collaborative residency with Andy Scarpelli! I am an artist who experiments with new ways of being in a technologized world. No doubt we are all exploring new ways of being together remotely given our current reality.

I make art by finding ways to bring very different ideas and methods together in synergistic, out-of-the-ordinary ways. I intervene in systems to create space for self-expression and agency. I am looking forward to bringing this weird skill I have into play in an experimental collaboration with Andy the biologist!

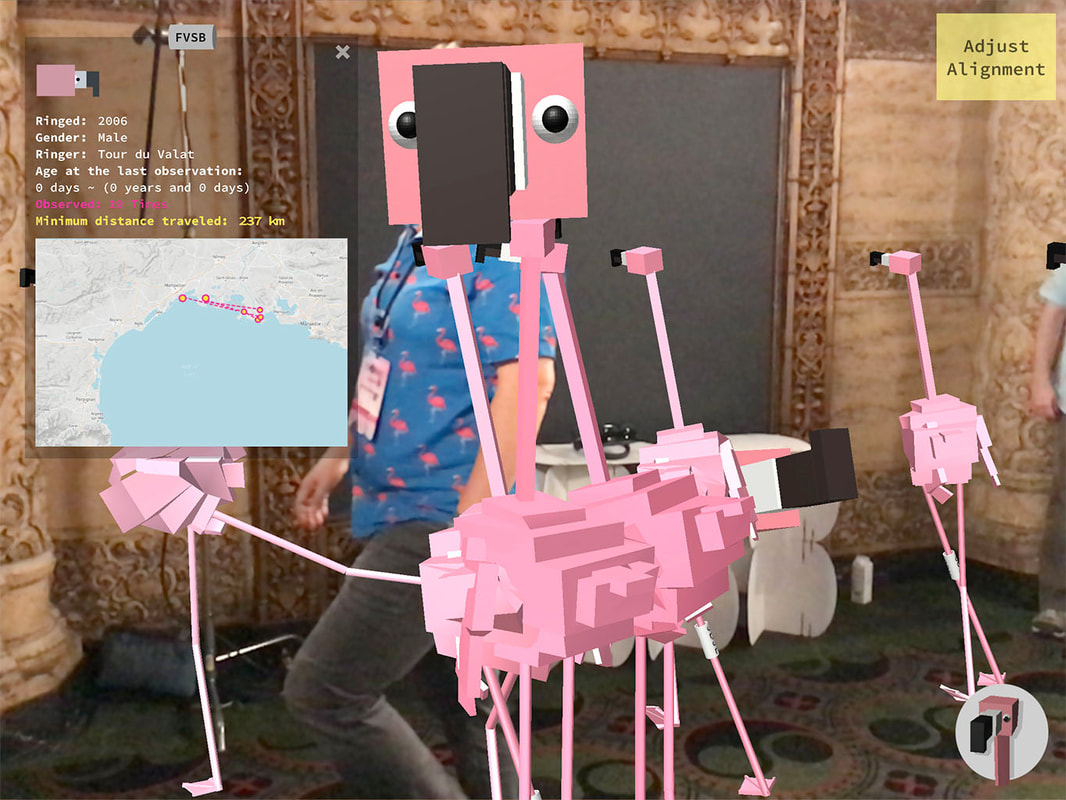

I live between New York and Austin where I am faculty of Studio Art at University of Texas at Austin. I recently returned to teaching after spending a few semesters traveling to artist residencies located near flamingo populations. Embodied research is a method of my practice, so I immersed myself in a virtual flamingo world. I sponsored and followed 20 wild flamingos online. I amassed books by biologists, scientific research papers, mugs, music and souvenirs—all about flamingos, and wore flamingo-print clothing every day for over a year as a uniform. I arranged meetings with biologists, conservation scientists, and flamingo experts and ultimately brought the public together in immersive, Mixed Reality experience-driven exercises that raised awareness about threats to flamingo habitats and breeding brought on by human activity and climate change. On a philosophical level, the exercises playfully imparted that humans are players within ecosystems and promoted interspecies kinship. Each iteration of Dance with flARmingos and FLARMINGOS included a call to action and fundraiser.

I believe art can be a powerful vehicle for sharing stories from science and can increase public engagement. With science funding diminishing, it is more important than ever to educate the public on science research. One question is, which stories are the more pressing stories to tell?

Another is, how differently do artists and scientists approach storytelling from their research and collected data?

Lately I have been creating stories that intervene in digital spaces like websites and social media. I have used the open source programming language p5.js to create 3d animations and 360 Web XR experiences for browsers. I have used Spark AR to publish participatory and interactive filters on Instagram.

Pick Up Artist (2020), Instagram AR effect for StoriesXFuture Ocean Innovation series,

released on UN World Oceans Day

I am a big fan of both open source and citizen science initiatives and I look forward to hearing more from Andy about his experience as co-founder of ChiTownBio, a public shared biolab in Chicago. I have spent a great deal of time researching how emerging technologies and citizen science are implemented in conservation science, and how citizen science projects within communities can facilitate change. I wonder if there is a way to bring storytelling and citizen science together. I am a member of the New Museum’s cultural incubator NEW INC where I am surrounded by founders, and I have definitely picked up an entrepreneurial itch!

|