|

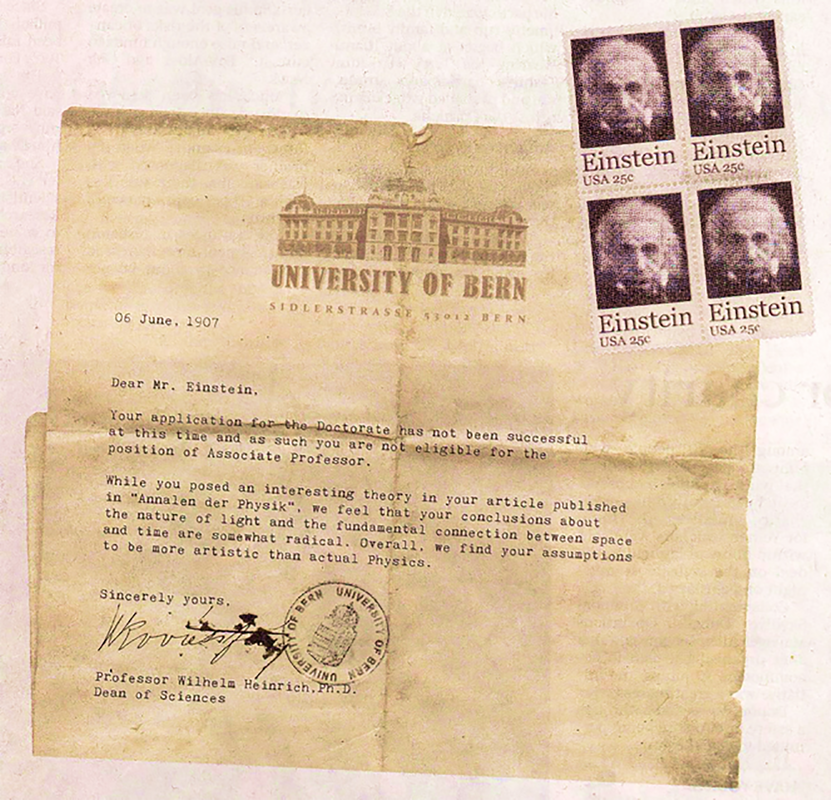

Stefanos When I was 8 or 9 years old, whenever someone asked me what I want to be when I grow up, I replied ‘video game developer’. It made sense: I was obsessed with my Game Boy and The Legend of Zelda, so making my own worlds and adventures and heroes seemed like the best career imaginable. For better or worse, there was not much of a job market on such things in the tiny village I grew up in in rural Greece. I doubt there was even a single computer there at the time and I am certain nobody knew what a ‘programmer’ does, so I got very perplexed looks when I told people of my aspiration. Throughout childhood I was exposed to a lot of great music through my mom and uncle and their friends. I still remember what a revelation it was to listen to Jean Michel Jarre’s Oxygene for the first time. It totally blew my mind. I remember asking my mom where these otherworldly ‘sounds’ come from. She told me it was from synthesizers. How do synthesizers make these sounds? They are programmed. Just like Zelda. In abstract terms, my childhood impulse to explore the world of Zelda, to design worlds like it for others to explore, to understand how Oxygene was made and to use that understanding to make new cool sounds, is the impulse to explore an intellectual world, figure out its rules and take on its challenges, and create new worlds with their own rules and challenges. In this sense, it is a very common impulse, shared by many people working in a variety of fields. It is also the same one that drives my science today. I had no idea of this commonality in my Zelda days. How can we expose common modes of thinking across disciplines? One approach that I find useful is to focus on exposing creative procedures rather than their end products - the design of a fun video game level, the synth wiring that generates a cool sound, the process that yields a captivating art piece, the algorithm that solves a hard problem. For example, sketches by the grandmasters of painting (like the one by Raphael above) are valuable, because they reveal how they arrived at their masterpieces. Pivotal scientific discoveries can be treated the same way. We can work collaboratively to build a dictionary that will allow future practitioners, teachers, and students to “translate” between counterpart concepts in seemingly disparate fields. We are in the very early stages of this process, and hence it often seems vague and ill-defined. But I believe that in time there will be sufficient vocabulary to become fluent in this translation. I am certainly not the only scientist who thinks this way. Diaa Although the relationship between the Arts, sciences, and technology has a long history, the role of every one of them to affect each other still controversial due to main two reasons. First, the ongoing scientific mutations and innovative technology that always impose new challenges in front of the artists and scientists to develop/reinterpret this relationship. Second, the natural path of this relationship within the context of the exchanging processes between the Arts and sciences, in which several interdisciplinary methodological approaches must be investigated. Actually, I am interested to be integrated in such cross-disciplinary collaboration not only to produce an interdisciplinary artistic project as an artist, but mainly to investigate the processes of the artistic creation under the umbrella of this relationship. In fact, the traditional path of this relationship usually goes from science to the arts to the extent that it can be seen as an intrusive relationship, in which artists use scientific techniques only in order to achieve a level of advancement in their visual scenes. For me, I am not totally looking for such path. On the other hand, several leading experiments and discussions, particularly in last 10 years, have been raised around the second and the most interesting and creative path that goes from the arts to sciences, in which unlimited approaches would be found to answer the question: How can the arts enrich sciences?! This is what I am looking for. As a specialist in Sciences of visual Arts, I am interested to figure out the nature of feed that can be produced in the artistic studios and New-Media Arts labs to be used in sciences, how can artistic practice-based research be a source/reference of scientific knowledge?! Perhaps Albert Einstein was one of the most prominent scientists in the modern sciences who may reached such an advanced level of the convergence/intersection between the arts and sciences in through his scientific imagination to process his thoughts to the extent that the scientific committee at the University of Bern rejected his application as an associate professor in 1907, where they felt a strong artistic sense of his scientific assumption. Perhaps their decision was reasonable in that time. Who could possibly imagine that the relationship between the arts and science will reach its current contemporary phase of intersection? In which science can be found in the core of some current artistic practices, and the arts can be derived from several current scientific disciplines! Through this virtual residence and with my honorable residence mate Stefanos, as we share several common interests, I am looking for investigating several interdisciplinary historical, technical, and conceptual processes that can foster deep understanding of the nature of the knowledge creation processes derived from the artistic practice-based research

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |