|

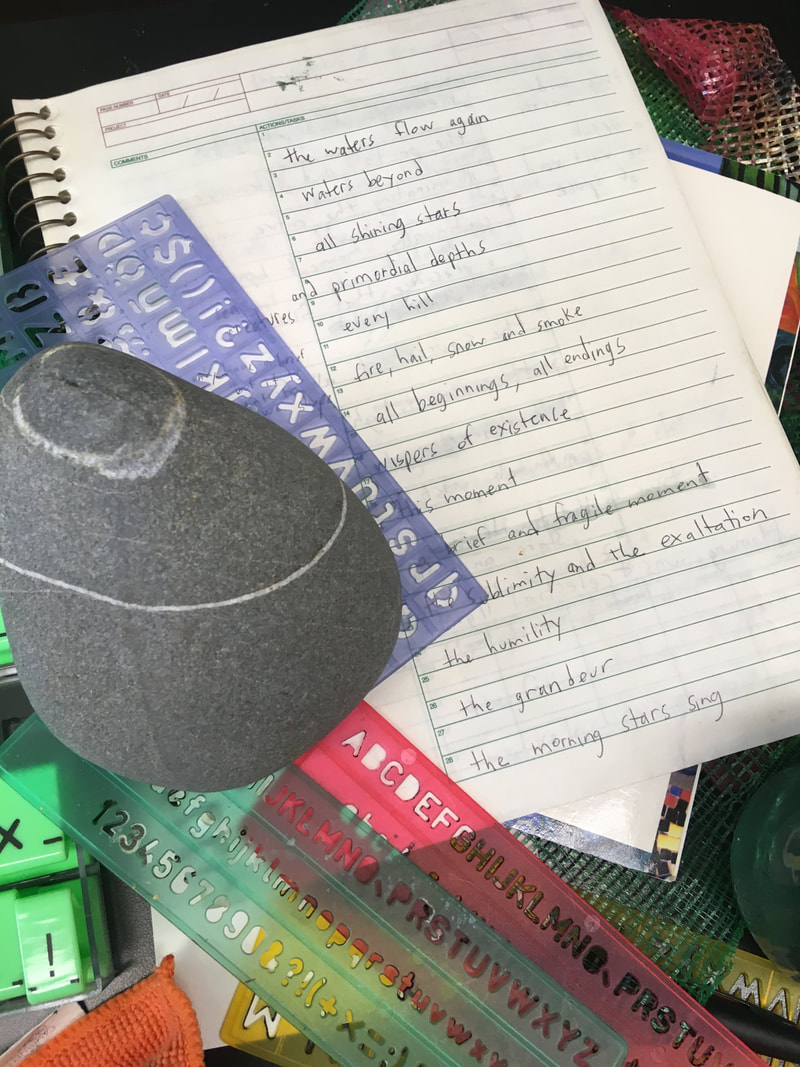

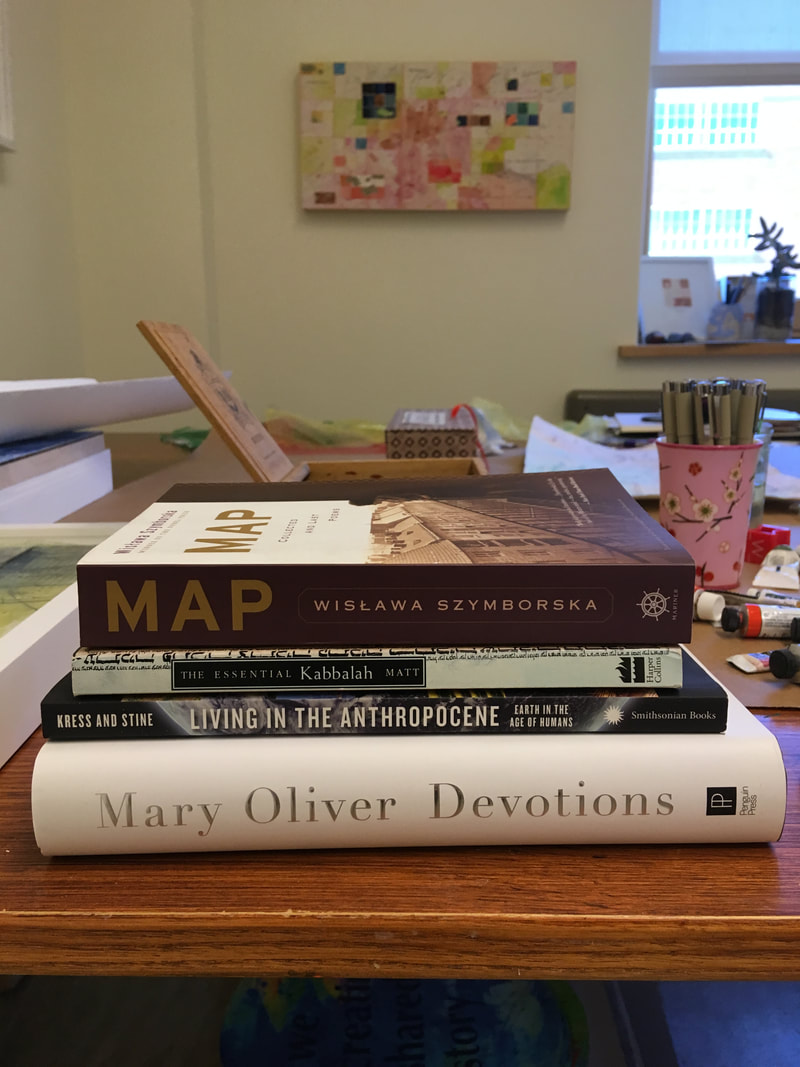

Karey I am a collector of words. When I read - fiction, non-fiction, news or poetry, I take notes and write down words and phrases that inspire me. I then re-combine the words and add some of my own to create places on my maps. I am currently reading the novel, “The Overstory” by Richard Powers. In this book, Powers addresses the fraught relationship between humans and trees: our need for trees as a resource and our blindness (sometimes) to our dependency on the existence of trees - particularly on old growth forests. I’ve also been reading about the Anthropocene - the current geological epoch which many geologists propose to call the “Anthropocene” because of the significant impact humans have on the earth’s geology and ecosystems. Most recently, I read a compilation of essays, “Living in the Anthropocene: Earth in the Age of Humans” edited by W. John Kress and Jeffrey K. Stine. Even before learning about the Anthropocene, my maps included deep time before humans were on earth and the eternal things that will remain once we’re gone. I took a hike this week-end and found some very happy mushrooms decomposing the forest floor and releasing nutrients for the trees and plants. I also spent time admiring the persistent weeds that grow between the cracks of my sidewalk and the moss that will grow on just about anything here in the Pacific Northwest. Nature gives me hope. Another inspiration for the words in my maps is poetry. I love the poems of Mary Oliver - her observations of nature and the connectedness of humans and our environment. Poem of the One World by Mary Oliver This morning the beautiful white heron was floating along above the water and then into the sky of this the one world we all belong to where everything sooner or later is a part of everything else which thought made me feel for a little while quite beautiful myself. And, I will leave this blog post with a relevant poem about maps by Wislawa Szymborska. In this poem, Szymborska reflects on the beauty of the world from the vantage point of a person looking at a map that has only greens and browns for land and blues for water: no markings for wars, droughts, floods or mass graves. Maps can reveal or hide everything. MAP by Wislawa Szymborska Flat as the table it’s placed on. Nothing moves beneath it and it seeks no outlet. Above - my human breath creates no stirring air and leaves its total surface undisturbed. Its plains, valleys are always green, uplands, mountains are yellow and brown, while seas, oceans remain a kindly blue beside the tattered shores. Everything here is small, near, accessible. I can press volcanoes with my fingertip, stroke the poles without thick mittens, I can with a single glance encompass every desert with the river lying just beside it. A few trees stand for ancient forests, you couldn’t lose your way among them. In the east and west, above and below the equator - quiet like pins dropping, and in every black pinprick people keep on living. Mass graves and sudden ruins are out of the picture. Nations’ borders are barely visible as if they wavered—to be or not. I like maps, because they lie. Because they give no access to the vicious truth. Because great-heartedly, good-naturedly they spread before me a world not of this world. Innisfree I really appreciate this opportunity and how it is pushing me to think broadly. Since last week I have been thinking a lot about representation and uncertainty, especially in relation to mapping and cartographic design. As I mentioned last week, representing uncertainty is a major problem in cartography, but, I think, one that isn’t often worked on by people who study cartographic representation because it is a “wicked problem” and because it is rare for scientists or others who create maps to want to make their maps or other data visualizations appear less certain. This week I messed around with ways to try to mimic Karey’s artistic style using GIS computer programs. I still need to do a lot of digging, both to produce something that comes close to her work, but also to better understand how the computer is producing the particular results I’m currently getting…Right now I’m borrowing and modifying existing symbols and fonts that others have created. These symbols themselves are made of several layers of images. The image below shows the symbol I used for creating the blue watercolor wash effect, but when I look at it in more detail, I can see in the settings that it is made of 4 overlapping layers combined to create the wash effect. Trying to mimic Karey’s style is an interesting exercise, but I don’t really want to be able to create her art using the computer, rather I’m hoping to explore the idea of uncertainly. My own work often involves a lot of uncertainty, which is one reason I have often tended to default to writing as a form, rather than cartography. In my work on sprawl and exurban development, I spend a lot of time studying the history of land use in an area and trying to imagine how the natural systems have changed over time or been impacted by human uses. But as we attempt to go back in history, archival records become more and more uncertain. In many parts of the U.S., European settlement began less than 200 years ago, so if we rely on written records, that only captures a tiny portion of the history of that land. So it is easy to tell the “history” of Medford Oregon (an area I have written about) starting with the gold rush in the 1850s, but focusing in this way ignores that Native people, the Takelma and the Umpqua lived in that area for many thousands of years. This is not my insight, a few years ago, Jessica Metcalfe PhD spoke about her work on fashion and creativity at the Rural Arts and Culture Summit, which I was attending. The phrase I remember is, “The history of this place did not start in 1850!” So many thanks to Dr. Metcalfe for pushing my thinking.

So today, for the first official celebration of Indigenous Peoples Day in Wisconsin, I want to think about who is missing from our representations of place. And, I think this, one of the things that art does better than science, represents the silences, the absences. So today, I’m thinking about the land I currently inhabit, near Menomonie WI, which is the unceeded territory of the Anishinabe and Sioux nations. Representatives from the Ahishinabe and Sioux nations don’t often get a space at the table when we make decisions about natural resource management. But I’m also thinking about all the living creatures that made up this place who were killed during the Euro-American process of mining this place for resources starting with beaver pelts, then logs, and today the growing of corn and soybeans.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |