|

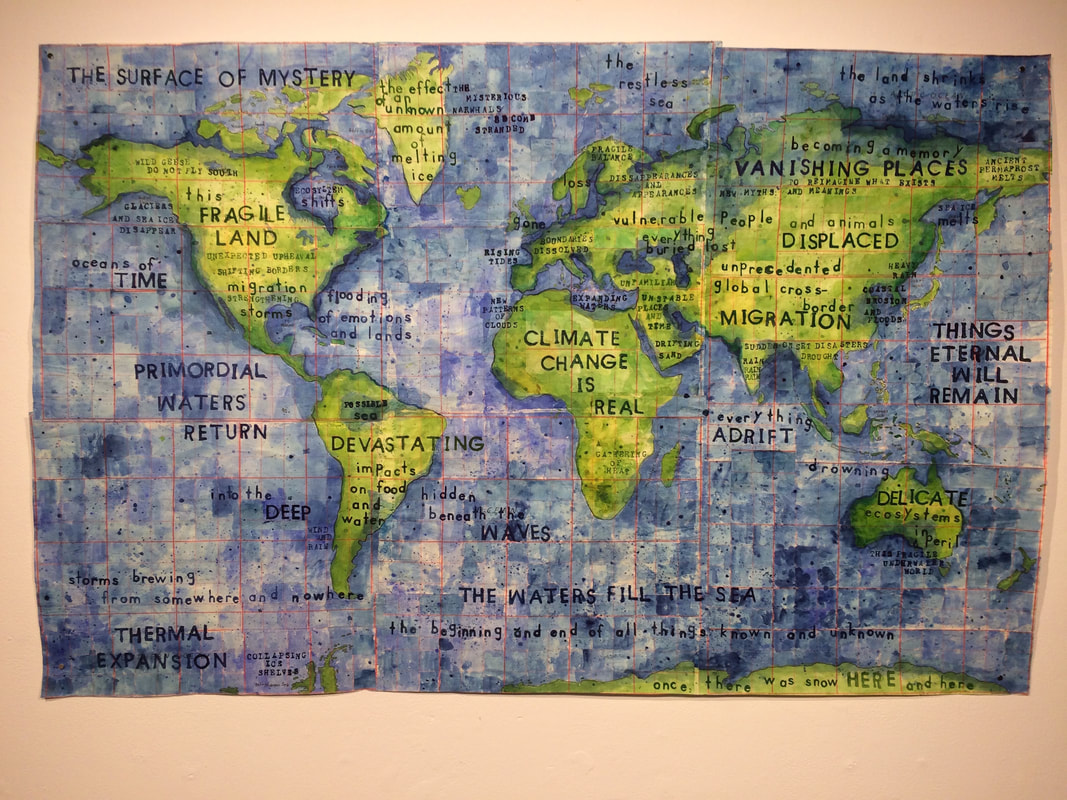

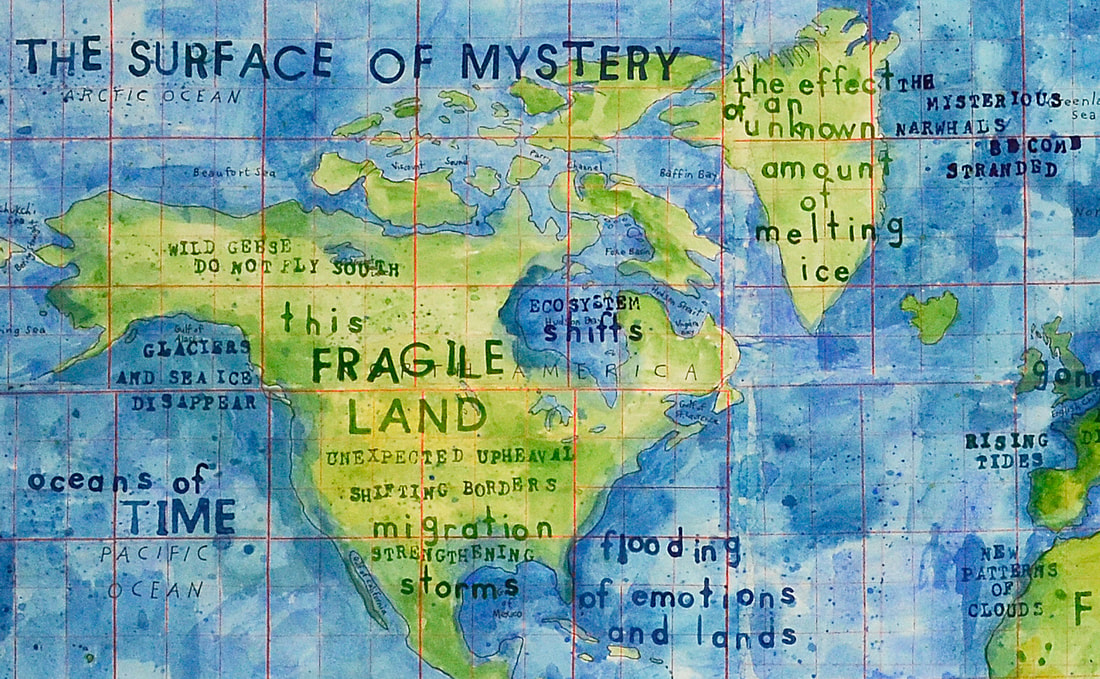

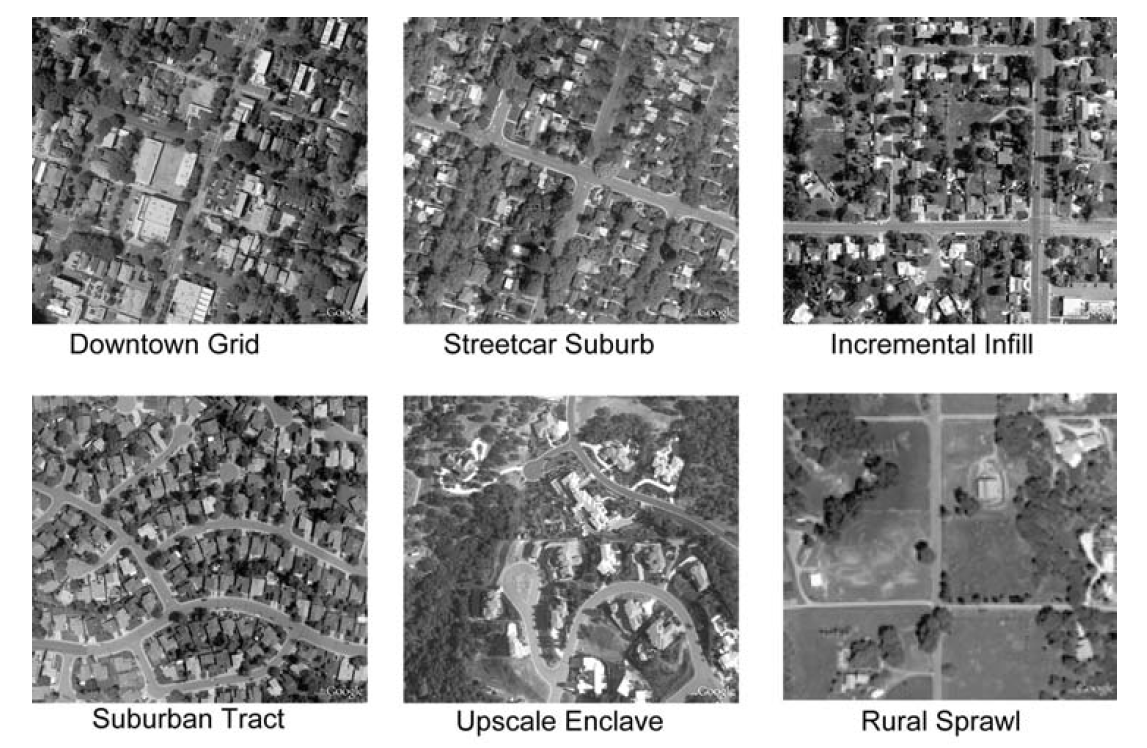

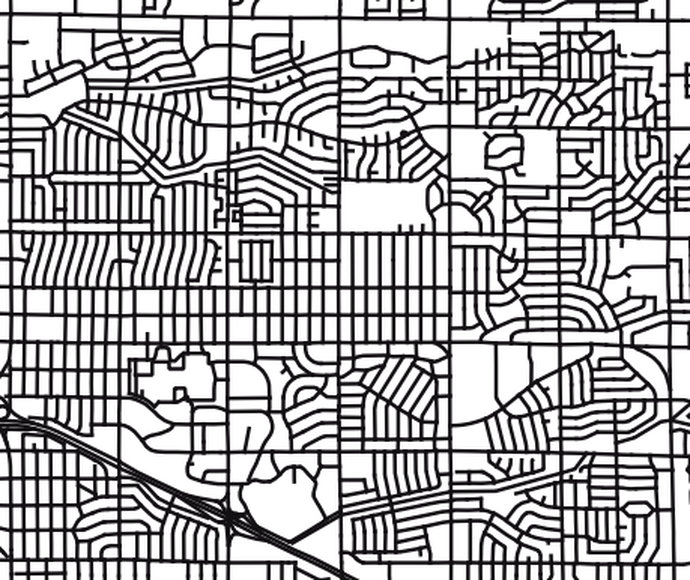

Karey One of the things Innisfree and I have been talking about this week is the possibility of using my artwork to create a template for real world maps. This inquiry requires me to break down the visual imagery of my maps into distinct elements: dots, shading, colors, and fonts and then describing the meaning of those marks. What do the dots stand for? The shading? The colors? But, the “symbols” in my maps purposefully mean more than one thing: dots can be birds, rocks or stars; lines can be roads, rivers or the passage of time; pools of color can be clouds or lakes or a mysterious presence. My understanding is that GIS is dependent on borders and boundaries around specific areas (land, water, sky, north, south, etc.). My work has no boundaries between one place and another, no distinction between time, space, water, and sky. Would it be possible to make a template for real-world maps that not only looks like my style but somehow adds an element of a blurring of things and a dissolving of boundaries? Two years ago, I made a map, “Climate Change is Real,” that was grounded in the real world but also included more abstract ideas about deep time and things eternal. I created “Climate Change is Real” as an artist, not a scientist. I didn’t use GIS to gather and analyze real world climate change data to reveal patterns, relationships and ideas. I painted a map that integrated real facts about the effects of climate change with poetic thoughts and emotional reactions to the changing landscapes and ecosystems of the world. I wrote emotional things like "flooding of emotions and lands" and "everything adrift" alongside facts such as "collapsing ice shelves" and "unprecedented global cross-border migration." “Climate Change is Real” was one way to integrate my painting style with real world maps. I’m curious to see if Innisfree and I come up with something else altogether. Innisfree I have had several thoughts after a productive and pleasant video chat with Karey last week. It is amazing how just this process of discussion and reflection opens up space for new thoughts to emerge. Talking to Karey about her work is pushing me to think about representations in cartography and in art. One thing that Karey said, that she was interested in abstract art, stuck with me. I don’t usually think of maps and abstract. The symbols on the map are meant to have meaning and significance, to represent real world objects, and yet, because the perspective of a map is unusual, everyday objects become pieces of broader patterns across the landscape, often appearing abstract. One of the toughest parts of studying land use change and urbanization is that computers still can’t “see” the patterns on the earth in the same way that the human eye can. Most remote sensing relies on analysis that senses the earth pixel by pixel. So, the earth is not made up of things: plants and rocks and animals, but of grid squares that reflect light. Grid square by grid square, it is difficult to distinguish a skyscraper from the sand on a beach. Until recently, computers could only piece together objects by analyzing each pixel, but humans could look at that pixel and make sense of it in relationship to other pixels nearby and the broader scene. This means that studies, like Wheeler 2011, of land use change and processes of urbanization involve time consuming human evaluation of aerial photography in order to understand how cities change and evolve. Recently, a new process, called object-based classification, has been developed, computers became much better at grouping individual pixels into groups of pixels in ways that form objects familiar to humans, trees, pavement, buildings. So, computers are beginning to be able to distinguish between objects in an image, and yet there is another scale of patterning on the landscape, that of neighborhood: how streets, trees, homes, fences and all the rest come together in distinct patterns that can tell us something of the history of their development. In a way, this pattern forms what might be considered abstract shapes. Viewed at this scale, individual objects disappear into the broader neighborhood pattern. But to a practiced eye, these patterns aren’t abstract. They reflect the processes that formed them, from eroding rocks, to home building, and tree growth. Which brings me back to another thing Karey mentioned about her work, that it gets her out of focusing on her own life and into thinking about processes happening at other temporal and spatial scales.

Karey and I discussed some more practical aspects of how we might go about creating collaborative works, but more thoughts on those will have to wait for another post.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |