|

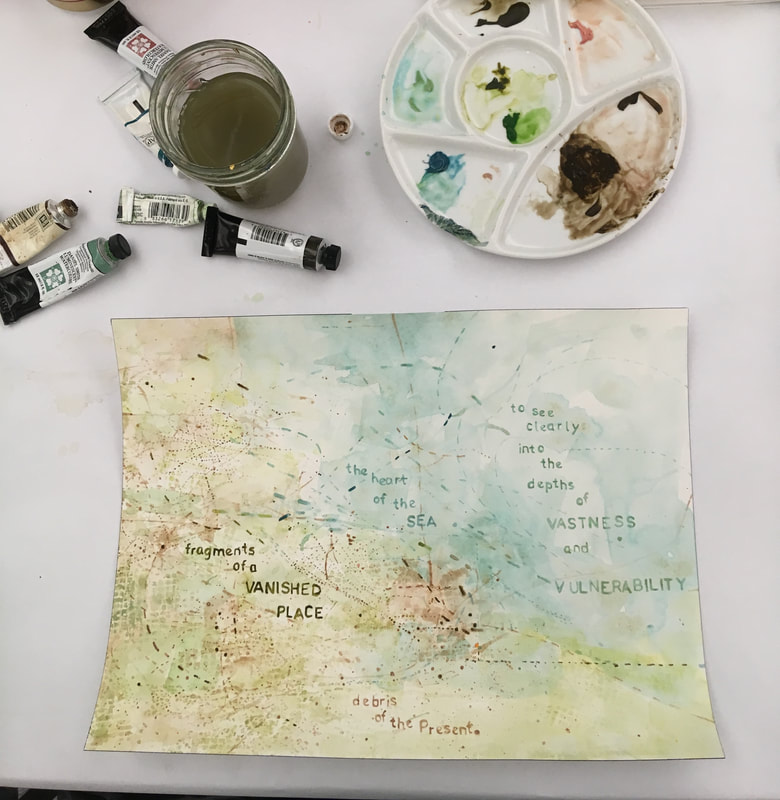

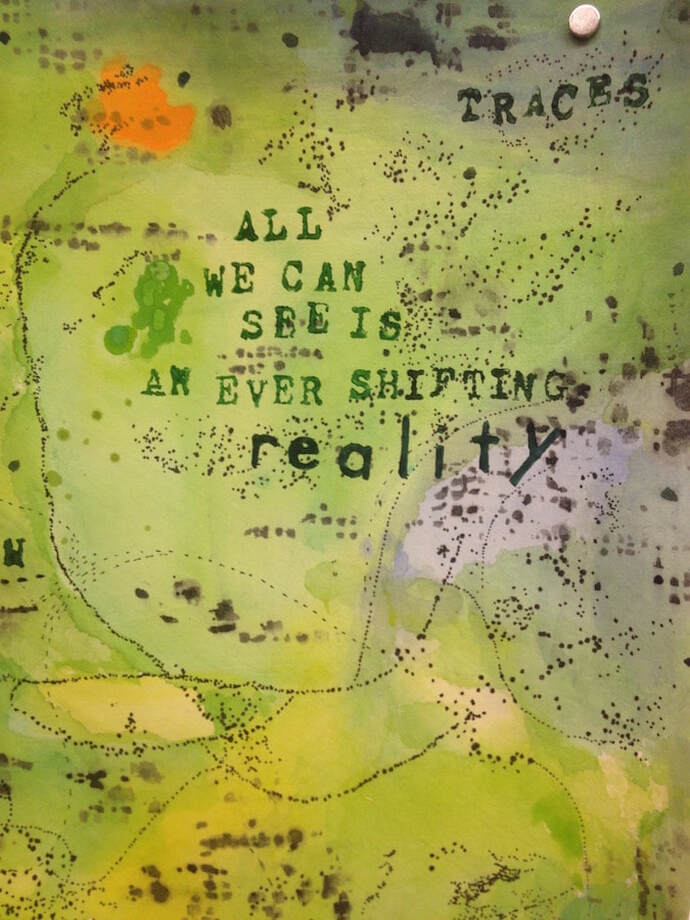

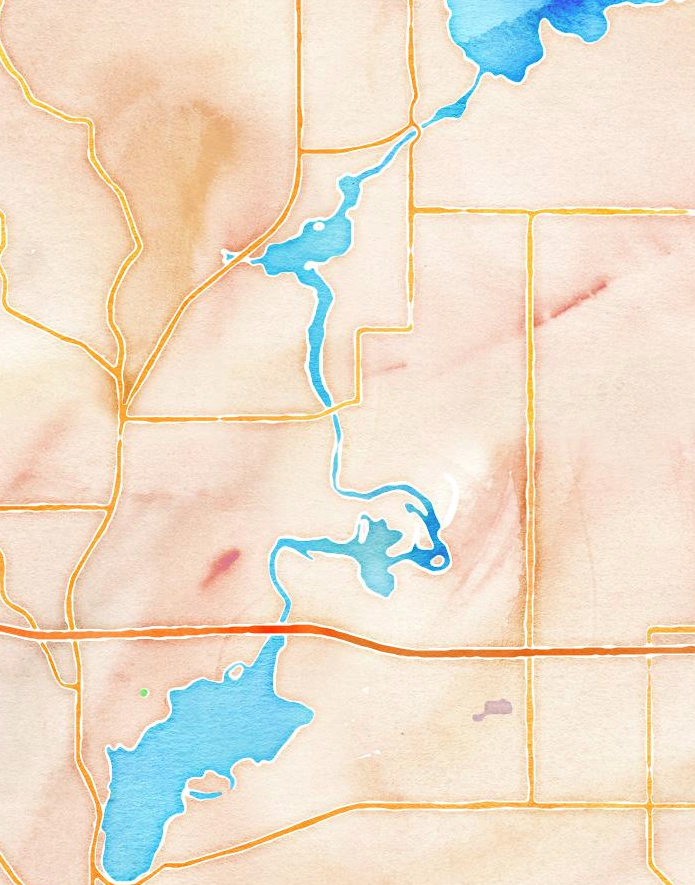

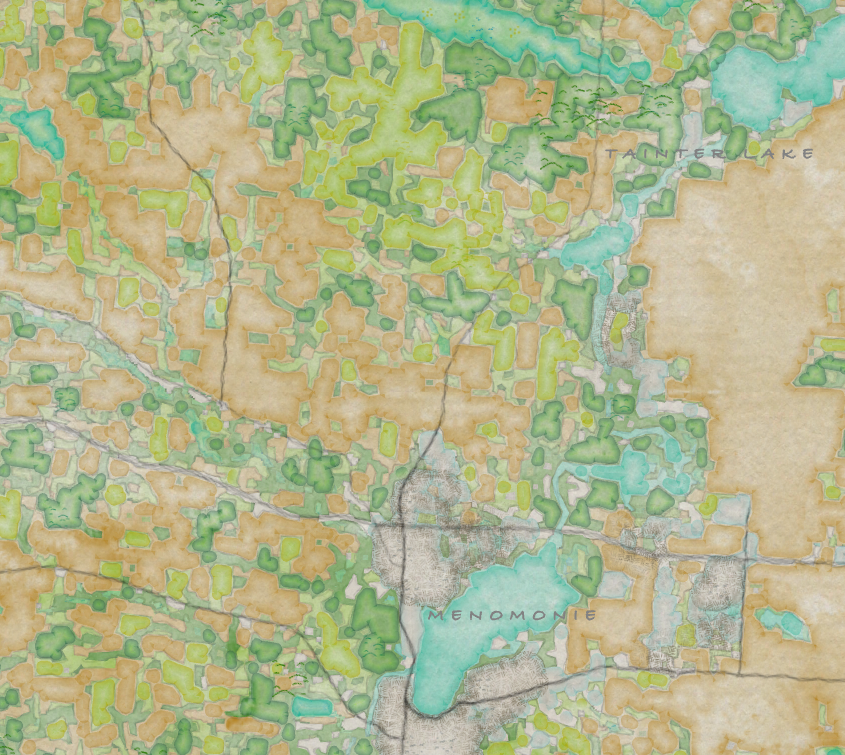

Karey "Who is the authority in making a map and also, does a map show reality or does it create the reality"? Innisfree posed this question in one of our first email exchanges and it particularly intrigued me. In my paintings, I create “worlds” and “locations” by labeling abstract marks (dots, lines, and areas of color). I am the authority in making the map, because the map is my own invention — the "places" on my maps don't exist in the real world. That said, although I don’t create maps of “real” locations, my art comments on and makes social, environmental, and spiritual issues more visceral and visible. Geographers also create worlds when they label their maps. But, for geographers, there is real political and ecological weight to their labels — who gets to name the land, the rivers and the streets? Who decides the boundaries and protected lands? These labels affect everything: ownership, accessibility, paradigms. Innisfree also asked me about the materials and process I use to create my maps. I arrived at using map imagery from my love of abstract art: the color, line quality and inventive spaces of Paul Klee; the energy and use of calligraphic marks in Cy Twombly’s work; and the inward-ness and silence of Agnes Martin’s art. I use watercolor and pens, stencils and stamps to paint my internal experience of place, as opposed to abstracting from what I see in the observable world. Two of my favorite map artists are Julie Mehretu and Mark Bradford. Both artists use the imagery of cartography to comment on the passage of time, history and politics. Like my own work, their paintings comment on the history of abstract painting, but also use map imagery to convey a “no-place” and an “everyplace.” In 1966, the painter Jean Dubuffet perfectly descibed my struggle to make visual my “mental space.” He said, “mental space does not resemble three-dimensional optical space and has no use for notions such as above and below, in front or behind, close or distant.” He goes on to say, “it presents itself as flowing water, whirling, meandering and therefore its transcription requires entirely different devices from those deemed appropriate for transcribing the observable world.” I'm fascinated by Innisfree’s knowledge and skill at mapping and GIS on the computer. I know very little about real-world map making and even less about computer programing. I was only recently introduced to the world of GIS in January 2019, when Jacob Tully wrote an article about my work in "The Summit" - the publication of the Washington State Chapter of URISA (the Association for GIS Professionals). : A Portable Homeland - Mapping as Art & Seattle's Inscape Gallery. Looking forward to seeing where these musings will take us. Innisfree This week, Karey and I have been discussing process. Karey described the process for creating her paintings as meditative. I have been reflection a lot on that and how my research processes and in particular, use of gis (geographic information systems), as a visual and analytical tool, might be similar. At first, I was a bit despairing because often working with computers and large datasets can be frustrating, rather than relaxing. Often, I feel as if I’m working to solve a problem, so the process often feels like. “Not fixed….not fixed…not fixed….not fixed…FIXED!” Certainly, the process of finding solutions to a problem is emotionally rewarding, but I wouldn’t say I find it meditative. But upon further reflection, I do find motivation around my research stems from a deep desire to get outside of myself and consider the larger processes at work. It is a relief and privilege to be able to spend time reflecting on things beyond the day to day stresses of one’s own life. I often find ideas about my research come to me when I’m in a meditative state, busy doing repetitive tasks like biking or gardening. The other piece of the process I have been considering is tools. I asked Karey about the tools she uses and thought about my use of computers in my research. I also searched for and dragged out some art supplies that had been in storage. Before gis, all cartography was hand drawn and processes required concentration and hours and hours of detailed work to produce a finished map. Computers have largely taking over the old processes of cartography, specifically because they were so labor saving, removing those repetitive processes that can be tedious, but also meditative. There are many cartographers today that combine manual techniques with digital ones, starting in one medium and moving to the other. Nothing on a computer can actually simulate manual illustration well, so it is not uncommon to create a map on the computer and then use that map as the basis for a hand-drawing final version. Recently, there have been efforts to create digital “map styles” that can quickly render the “look” of a particular hand drawn map. Stamen design famously created a digital map style called watercolor, which can be applied to all sorts of map data to produce maps of anywhere on the globe in the same visual style. This made me think, would it be possible to create a digital style from Karey’s work that would allow the computer to create a digital map of a real part of the world, but in the “style” of Karey Kessler? It might be something like this second watercolor style made by cartographer John Nelson. I did experiment a bit with using this style to create a land cover map of the area near where I live, but so far, I’m frustrated with the results.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |