|

Karey Last week, Innisfree shared an article with me from emergence magazine titled, Counter Mapping, by Adam Loften & Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee. It’s about Jim Enote, a Zuni farmer who is also the director of the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center in New Mexico. He started a mapping project with Zuni artists to create maps of the Zuni land that offer counter-narratives to the more conventional Western maps of the area. The mapping project stems from the realization that: modern maps hold no memory of what the land was before. Few of us have thought to ask what truths a map may be concealing, or have paused to consider that maps do not tell us where we are from or who we are. Many of us do not know the stories of the land in the places where we live; we have not thought to look for the topography of a myth in the surrounding rivers and hills. Perhaps this is because we have forgotten how to listen to the land around us. The article goes on to state: The [Zuni] maps are in many ways an invitation: How would you map the places that live in your memory? What are the voices of the land that are forgotten, unheard? To ensure the resilience and well-being of the places where we live, we cannot assume that land is simply ours for the taking, a means to our own ends. The Zuni maps remind all of us that we, too, must take the time to deeply listen, to hear and share stories in which we and the land have equal voice. Over the past few weeks, while working with the idea of map-poems with Innisfree, I’ve been researching the land I live on in Seattle. All the maps I have been looking at are “modern” maps created in the past one hundred and fifty years from a Western perspective. Even the geologic maps that tell the deep time of the land around me leave out any element of myth or memory. I have only lived in Seattle for a little over eleven years. Being so transient, I wonder, what does it mean to be connected to the land of Seattle? And, I am not alone — most of the people currently living in Seattle moved here within the last one hundred years (thousands moved here just within the last ten years). How much do we know about the land we live on, where our food comes from, and the source of the water we drink? Also, what does it mean to be connected to the land in Seattle when most of the land itself is covered with asphalt and grass? Some of the ways my family and I have connected to the land we live on are:

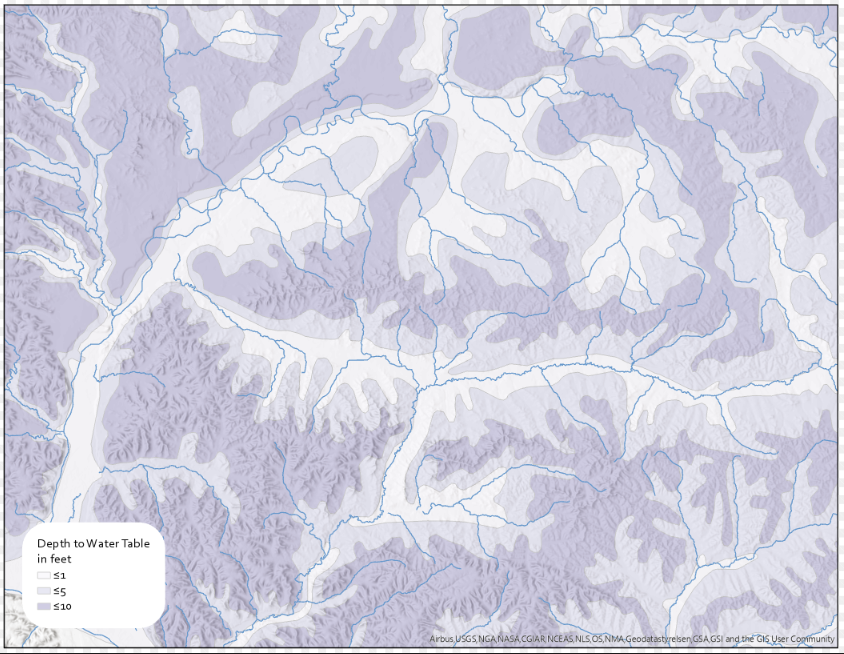

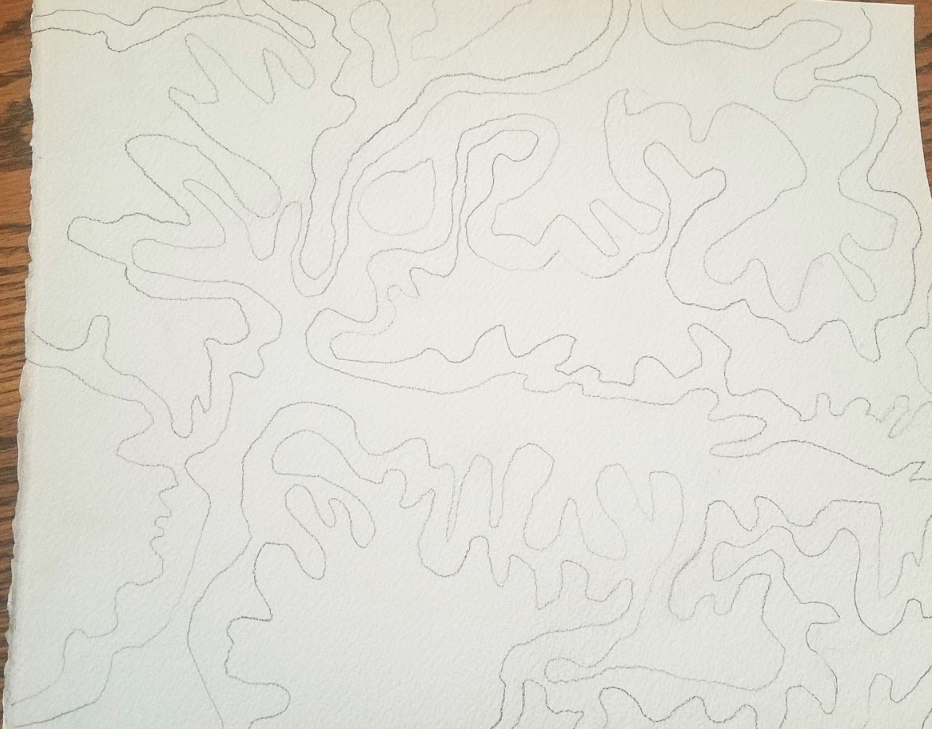

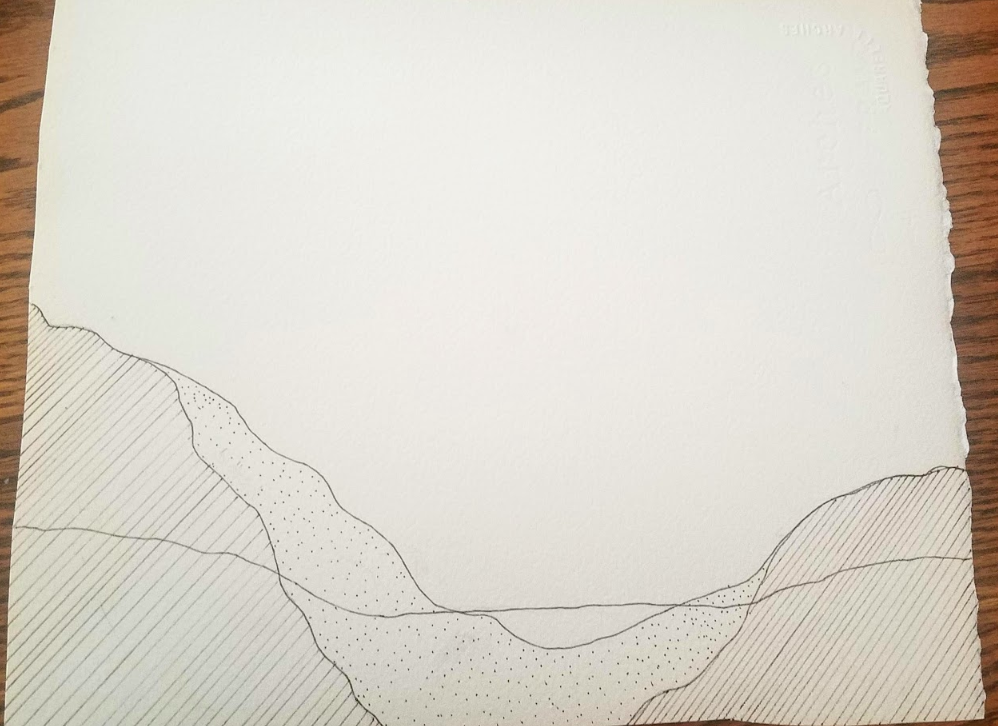

I sincerely hope that my children have a connection to Seattle that goes beyond Google Maps and the GPS maps that we use every day to get from place to place. In order to take care of this one earth we all live on, we need to start with the land beneath our feet. Karey and I had an interesting discussion this week, but I’m still struggling with the best way connect our work. She has been exploring the land histories and historical maps of Seattle. And I have been exploring historical maps of Western Wisconsin too. This week I found some exciting maps for my research from 1876 showing rock types, but also areas of prairies and wetlands. Both prairies and wetlands have largely been destroyed by agriculture over the last 150 years. Wetlands in particular have the potential to absorb pollution. I would love to be able to envision the amount of wetlands that have been lost and estimate the impact those lost wetlands could have had on water pollution. I’m also trying to take inspiration from that map and attempting again to develop some skills with the watercolors. I have also been thinking about groundwater and the patterns, in three dimensions that water flowing above and below the ground makes. Reflecting on Karey’s work made me consider the patterns and how they suggest a map while still being mostly abstract. And I think it is the types of patterns combined with the use of words to label parts of the image. So, I thought it might be helpful to focus on patterns in maps. I have been thinking about groundwater because nitrates are polluting water wells around Wisconsin. Nitrates can cause illness in young children and other people with weakened immune systems. The pollution is coming from the many dairies and livestock operations around Wisconsin, but also from leaking septic tanks produced by the large number of rural homes around the state. Particularly in areas with karst geology, contaminants can move underground as water moves. I have been exploring gis data layers related to topography, bedrock types, and groundwater. This map shows part of the Driftless shows topography, waterways, and approximate depth to the water table. You can see the map has some problems, including streams that seem to suddenly start and stop, and water table depth that only shows depth in three approximate categories. So I am starting to draw a handmade version focusing on the interesting pattern that the water table makes. I’m hoping to use a watercolor wash to better show the uncertainty of the water level. Based on the 1876 geology map, I’m also working on a hand-drawn cross section showing water and rock.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |