|

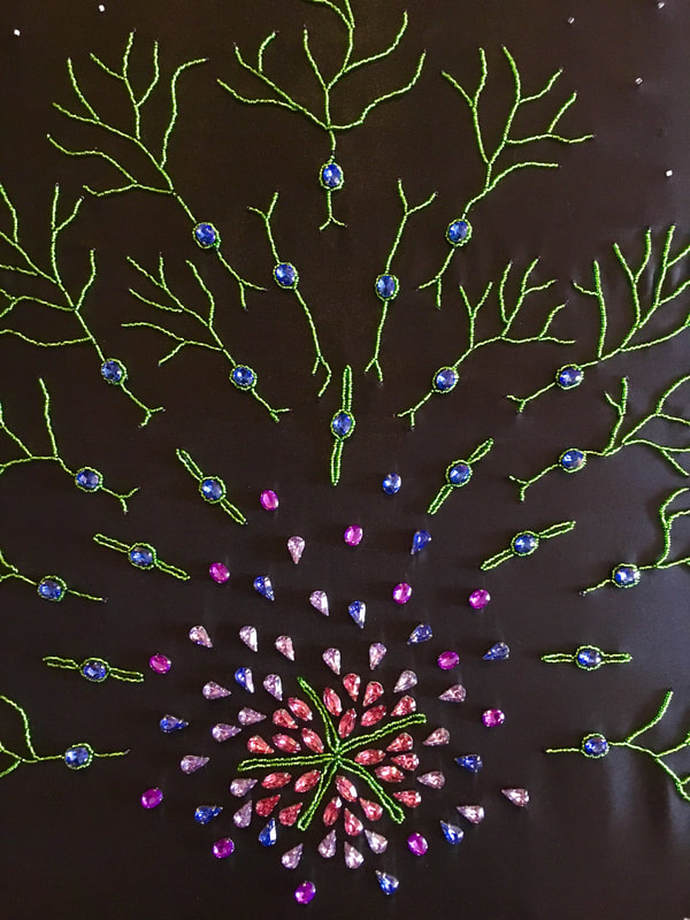

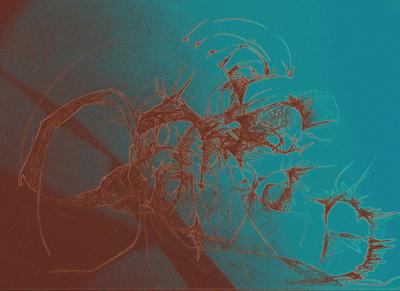

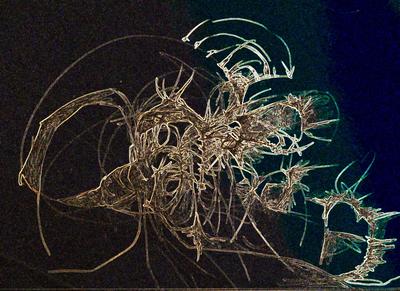

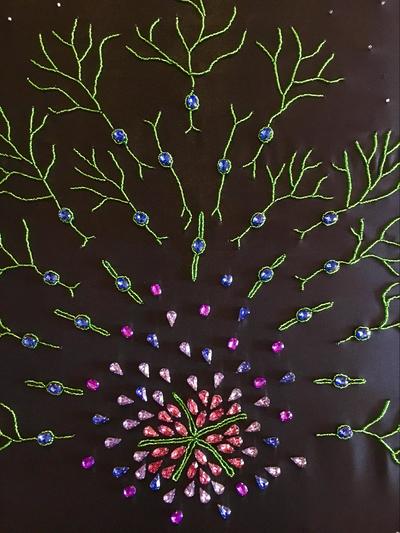

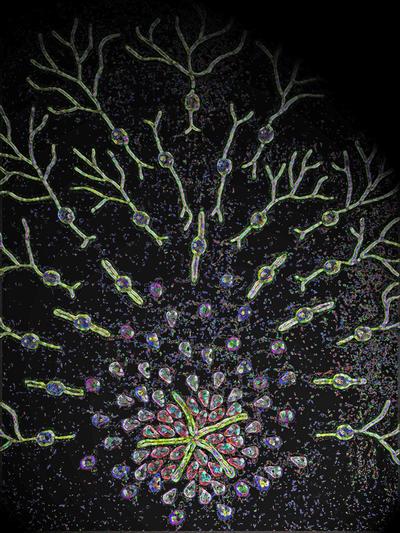

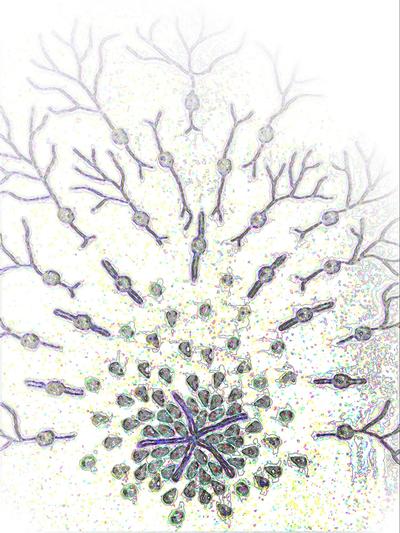

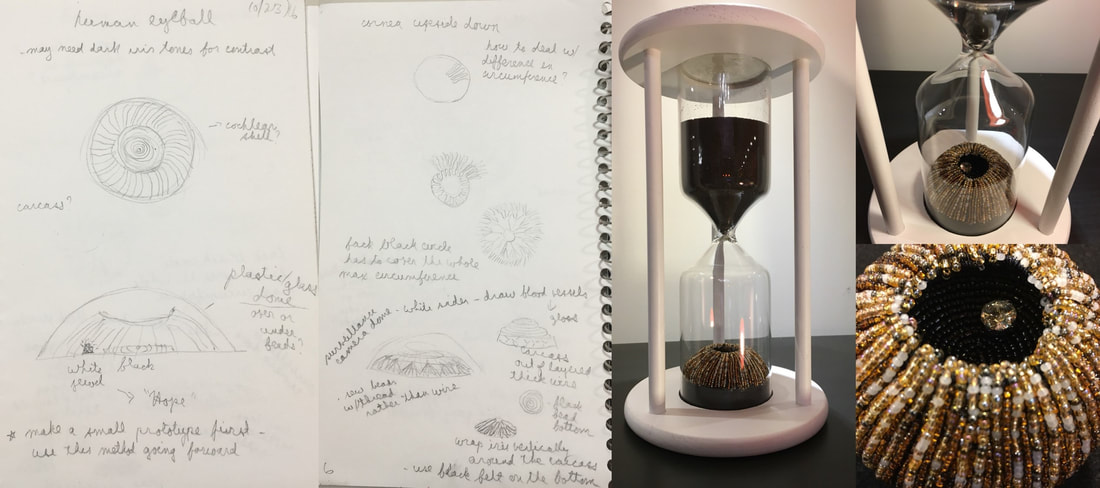

Yana Several years ago, as I was working on developing my scientific career, I was presented with the Myers-Briggs test. Myers-Briggs test is a widely accepted assessment of one’s own personality. It is meant to provide information to begin understanding your own qualities. This includes identifying your strengths and weaknesses and finding ways to take the best advantage of applying them in our daily and professional life. While I completely agreed with 3 out of 4 characteristics, one came as a surprise. I was told that I rely more on intuition than on my senses and understanding. As a scientist, I would have thought the opposite - that I process information primarily through observations, which in turn inform my decisions. When I work on my art, there is an internal battle of these two sides. This week, Darcy and I began discussing what drives our work. I feel like no matter how deep I get into the creative process, my scientist hat never comes off. I do my best to stay true to the scientific form and it takes a lot of will power for me to venture into something a bit more abstract. In my sketch notebook, I first come up with a “protocol” for the project. This consists of a very general sketch that just captures the main idea; followed by several mini-sketches, in which I brainstorm the way to convert it into a 3D structure. How can I thread the wire to make the structure stable? It is almost akin to a quick blueprint.  Yana Zorina, “Hope” 2018 Yana Zorina, “Hope” 2018 Over the last several months, I have listened to a number of podcasts, where artists talk about their process. In a lot of interviews, artists talk about putting down the key aspects of an idea and then letting the art guide the process. They like to see where it takes them if they let go of all reservations. Sometimes mistakes can lead to the greatest discoveries (this applies to both art and science). However, if a painter dislikes something about their work, they can cover it up and restart a section, even if it means temporarily losing an element that worked well. Unfortunately, beadwork is not as forgiving as canvas and paint. This potentially means that there is a much lower chance of “happy mistakes” if you had a certain pattern in mind. Nevertheless, in a lot of my work I tend to “think on the fly” and create new components based on what would fit well with the existing composition. This was especially true when I was working on “Sunrise”. In a more recent piece, I used a beading technique that is even more difficult to undo. It took a great deal of self-control to let the work flow freely and allow for a certain element of biological stochasticity, rather than striving for geometrical symmetry. Given Darcy’s interest in the theme of palimpsest, I would love to explore the possibility of adding more (free-formed) layers to my work. Despite being 3D, all of my works have been made as a “single layer” and creating beadwork in several tiers could provide for more richness and complexity. We are beginning to explore how I could create more dimensions in my work by adding network patterns that Darcy would generate. Darcy This past week, Yana and I have talked about the process of planning and making art. At what points in the process are we consciously problem solving as we go and when does the imagemaking become responsive, immediate and subconscious. Many visual artists use sketchbooks to plan larger more finished pieces but I often do the opposite by drawing spontaneously in my sketchbook to inform a larger more deterministic finished artwork. I think the interesting question is how does this image development process look for each of us. What are the ways in which we create images; when are they analytical and when, intuitive? I use my sketchbooks to play. I draw randomly and responsively, I would say intuitively. I work into images I have started months or even years ago. I explore and experiment constantly. Many of my sketchbook images are abstract drawings. I am powerfully drawn to abstract images because I don’t want to be distracted by a recognizable image. Evenso, My abstract sketchbook drawings are often evocative of the natural world and its laws which, makes me question whether there is ever any abstract images that do not carry in them our more concrete experiences of the world whether we are making or viewing art. See the “beholder’s share” by Ernst Gombrich, The Story of Art, 1950 One way I “study” my intuitive drawings for their content, insights and possibilities is digitally. The following series started with a photographed sketchbook drawing which I worked up into a series using Photoshop. The series is called Macromolecule because that is what I was thinking about as I rendered this series. When I drew it originally in my sketchbook, no such evaluation was in my mind; it was an open ended drawing with many possible interpretations. To bring this process into the collaborative work that Yana and I are doing, she suggested that I render some photos of her neurobead work. This was a very satisfying way for me to explore her imagery. I was working with Gombrich’s idea of the beholder’s share. Briefly the beholder's share is the life and art experiences we bring with us whenever we view a piece of art. Art pushes us to see the world in a new way but that view must also contain our previous experience of art . Our responses to art must be primarily intuitive because they are informed by the complex and layered memories all of which cannot be conscious in any given moment. Below are several digital renderings I did of the orginal photo Yana sent me.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |