|

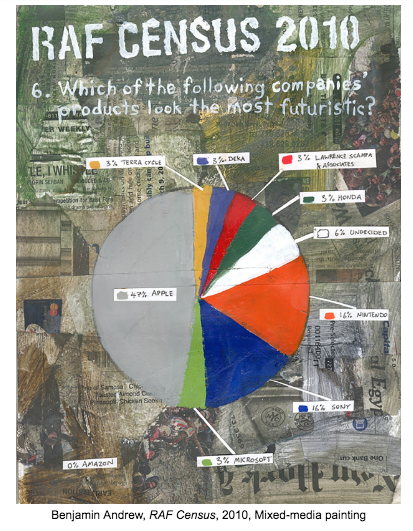

Ben's update Where does your water come from? One of the most stirring results of examining water contamination like the ongoing disaster in Flint, Michigan is that it reveals the innate trust in the infrastructure beneath the sink. Many people today have no idea how their cars or computers work; there’s a trust that develops when complex mechanisms appear to function well over time and most people would never seek to uncover the intricacies of their water supply unless there was a problem. After looking at the overwhelming amount of water data online (see previous), I’m thinking about gathering my own from the populace. A general poll asking people about water utilities and contamination could result in two types of responses: 1. Awareness of actual dangers and a sense of just what public knowledge contains 2. Hilarious misconceptions about reality As catalysts for art and design, both types of responses could prove useful. I’m imagining diagrams, figures, and PSA-style videos about where tap water comes from and the microscopic features it contains. Response type two could be a great hook for engaging audience in the otherwise dull minutiae of water chemistry, and for sure-fire hilarity I’d love to pose questions to children about their conceptions of water utilities. Unlike a traditional survey, these journalistic responses could be curated for specific points of interest. For an artist tackling a subject as big as water, using someone else’s ideas as a launching point would certainly help. In 2010 I designed a survey to test assumptions about how people envisioned the future: what movies are most emblematic of the coming years? What shapes and colors are futuristic? And will it be utopian or dystopian? I made paintings of the results, but only reached a few dozen people with my xeroxed questionnaire. Three years later I interviewed people throughout Baltimore as part of my project the Chronoecology Corps, collecting stories about people’s favorite memories of nature. I focused on getting them to describe in detail physical sensations like the sound of the ocean or the feeling of walking on moss in your bare feet (I was pretending to be a time traveling scientist from the future who had never experienced these things). This sort of democratic recording is important because it puts the onus on the audience to create meaningful experiences, and by recycling their stories in my own work, there’s an exponential gain in connected lives— but since I’m working with the SciArt Center now, I’m curious if I can make any future surveys more rigorous and scientific.

The National Science Foundation explains that two concerns when designing a scientific survey are sample selection and the type of question. A self-selected responder (such as someone who seeks out an online poll or calls a phone number) is likely to be biased, and unless the survey can be distributed to an extremely large audience, it’s best to develop a “representative sample” chosen randomly. If you’re familiar about your target audience, you can use “stratified” sampling to select participants from diverse sections of the population. Unsurprisingly, the NSF recommends using “objective” questions that do not imply bias or emotion. As an international collaboration between artists on both sides of the Atlantic, I’m not sure what our target audience would be for this project, but we’ll see where it goes. I’m also trying to maintain the focus on activist engagement, and wondering what audiences would provide stirring responses, who would benefit most from water safety data, and what would provide a good show for our readers. But I guess I’m biased.

1 Comment

|

Visit our other residency group's blogs HERE

Paz Tornero is an artist, visiting professor at the University of Caldas in Colombia, researcher at the University of Murcia, Faculty of Fine Arts in Spain, and visiting fellow at the Institute of Microbiology (USFQ) in Ecuador.

Benjamin Andrew is an award-winning interdisciplinary artist, storyteller, and Instructor at Pennsylvania State University.

|