|

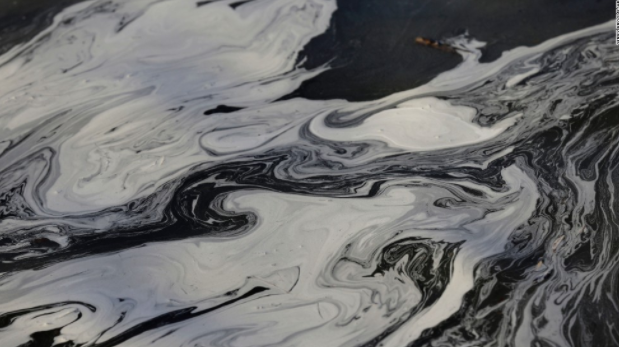

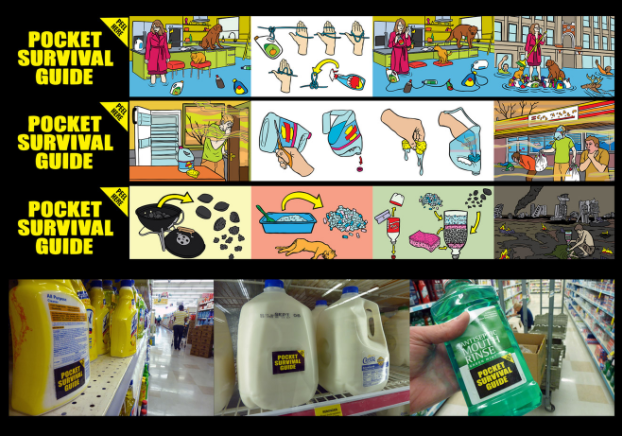

Written by Ben Last week I wrote about the swirling ecosystem and environmental threats of of Mar Menor and my somewhat less exotic residence in State College, Pennsylvania. Rather than tackle that intercontinental mix of nature, industry, and culture, this week I’ll just ask a single question: what’s in your drinking water? My collaborator Paz Tornero and I have both shared our own local stories of contaminants, and stories of water pollution have hardly left the public eye after Flint, Michigan. The essential right to clean water has come up repeatedly in the American Presidential election, and just recently the chief epidemiologist from North Carolina resigned to protest an ongoing cover-up of toxins leached into drinking water from a 2014 spill of coal ash. Anyone who gets their water from a private well (let’s call them Well People) may get their water tested regularly, but having lived in cities my entire life, I’ve always assumed the water coming out of my kitchen sink was regulated, or at the very least, periodically tested by someone to assure a lack of deadly poisons. Setting aside the issues of trust and oversight for a moment, I was curious what options are even available to someone interested in water quality? And how would you define quality anyway? Thirteen dollar kits are available for testing your water with a variety of color-changing swabs; chemical reactants act more or less like pregnancy tests, except that turning blue could mean you have herbicide in your coffee. These tests are apparently not totally reliable, and won’t give you results as detailed as those garnered from lab work. Luckily you don’t need to be a chemist to get those results, thanks to the high tech solution of pouring water in a plastic tube and mailing it away in a box. Companies like Ward Labs will analyze your water down to the last molecule for a variety of prices, a service I was vaguely aware of from my experience homebrewing beer. Dedicated beer geeks who reach the limits of carefully processing and combining hops, malts, and yeast, can turn to the fourth ingredient of beer (water) to fine tune the flavors and chemistry of their ferments. I’ve never gone to such lengths for my own brewing, even my experimental art beers made with single-strain yeast cultivated from samples of wild microbes. Getting your water analyzed will eventually reward you with a printout listing the proportions of contaminants like herbicide, gasoline additives, lead, coliform bacteria like e. coli, and uranium byproducts. At trace amounts, the aforementioned pollutants are listed as “acceptable contaminants” by the local water authority where I live, which means that low levels of them are just dandy, and separate from aesthetically unpleasant “nuisance contaminants” like chlorides and sulfur. I’m curious how these analysis tools might be used by activist artists like myself and Paz, and how they can be made more accessible, because, let me tell you, the EPA does not make this stuff easy to find. While the EPA website features a map where you can click on your state for local water resources, I eventually found myself downloading an Excel spreadsheet of every accredited water lab in Pennsylvania and their phone numbers, the later of which are the suggested course-of-action for those concerned about their water quality. One of the labs listed for my county was “Coca Cola Refreshments.” As I imagine how this convoluted process could be reinvented or transformed, I’m reminded of the illustrator and saboteur Packard Jennings, whose Pocket Survival Guides have continually made their way into my lectures for art students as a source of inspiration and hilarity. One of the guides even shows how to construct a basic water filter using household ingredients. Where is the line between post-apocalyptic speculation and real-world preparedness? What information is essential for water-drinkers around the world, and how can it be communicated clearly? What data already exists on these subjects and what tools do people already having access to?

1 Comment

|

Visit our other residency group's blogs HERE

Paz Tornero is an artist, visiting professor at the University of Caldas in Colombia, researcher at the University of Murcia, Faculty of Fine Arts in Spain, and visiting fellow at the Institute of Microbiology (USFQ) in Ecuador.

Benjamin Andrew is an award-winning interdisciplinary artist, storyteller, and Instructor at Pennsylvania State University.

|