Show image by Jared Vaughan Davis.

"SUBMERGED"

a virtual & pop-up exhibition

164 Orchard Gallery

June 2018

a virtual & pop-up exhibition

164 Orchard Gallery

June 2018

“In one drop of water are found all the secrets of all the oceans;

in one aspect of You are found all the aspects of existence.”

- Khalil Gibran

Water is everywhere. Comprising up to 73% of the human body, three quarters of our planet’s surface is covered in water between our oceans, seas, rives, and lakes. We are inextricably connected to water in its variety of forms.

As science continues to reach new frontiers in exploring space and mapping the human brain, our knowledge and experience in Earth’s largest waters - the ocean - remains limited. The Mariana Trench, the deepest known area of the ocean measuring at 36,000 feet down, has only been visited by piloted missions four times, two less times than we’ve visited our celestial neighbor, the moon. With only 5% fully explored, the mysteries of the ocean and its true nature persist.

As staggering in quantity as the ocean is in size, our estimated 117 million lakes contain worlds of unknown history and lifeforms. From the jellyfish species recently discovered in the Kodaikanal Lake, to the biodiverse depths of the 25 million-year-old Lake Biakal, our understanding of the potentials of water and the life it supports continues to grow.

Touching so many parts of our lives from habitat to food to travel, our planet’s water bodies are a timeless source of inspiration for investigation by artists and scientists alike. Now, with the advent of technologies like undersea drones, we are able to expand our senses remotely and learn more about the alluring and ever surprising topographies of our waters and the life that occupies them.

Curated by Marnie Benney

As science continues to reach new frontiers in exploring space and mapping the human brain, our knowledge and experience in Earth’s largest waters - the ocean - remains limited. The Mariana Trench, the deepest known area of the ocean measuring at 36,000 feet down, has only been visited by piloted missions four times, two less times than we’ve visited our celestial neighbor, the moon. With only 5% fully explored, the mysteries of the ocean and its true nature persist.

As staggering in quantity as the ocean is in size, our estimated 117 million lakes contain worlds of unknown history and lifeforms. From the jellyfish species recently discovered in the Kodaikanal Lake, to the biodiverse depths of the 25 million-year-old Lake Biakal, our understanding of the potentials of water and the life it supports continues to grow.

Touching so many parts of our lives from habitat to food to travel, our planet’s water bodies are a timeless source of inspiration for investigation by artists and scientists alike. Now, with the advent of technologies like undersea drones, we are able to expand our senses remotely and learn more about the alluring and ever surprising topographies of our waters and the life that occupies them.

Curated by Marnie Benney

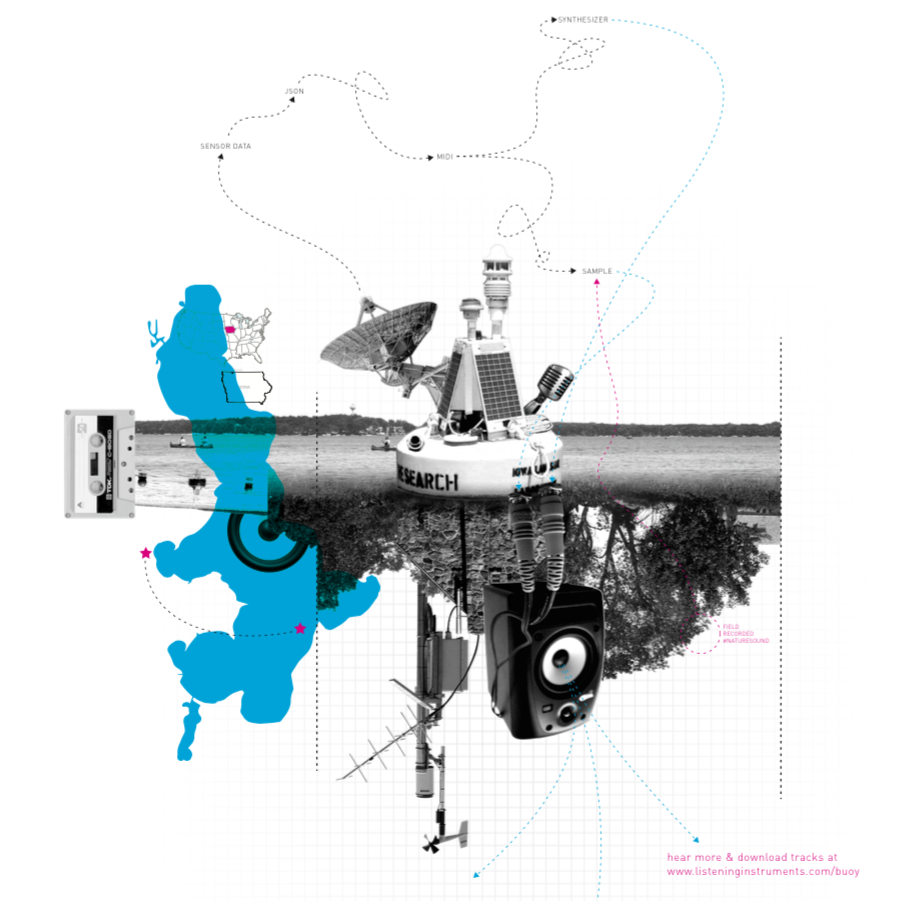

ALEX BRAIDWOOD

|

During my time as an Artist-in-Residence at the Iowa Lakeside Lab biological field research station, I created the Buoy Music project. Lakeside Lab manages a buoy in West Lake Okoboji that has an array of sensors monitoring things happening both below and above the water surface. Every ten minutes, the buoy is reporting things like precipitation, wind speed, water surface temperature, water temperatures at two meter increments to the lake bed, carbon dioxide levels, dissolved oxygen levels, and other readings. These values are stored in a database, reported live to the web, and available through a mobile app. The Buoy Music project I created uses this data to develop musical compositions that reflect that status and changing conditions of the lake. Essentially what the project does is use data from five sensors to control five virtual musical instruments. Each instrument is associate with a specific sensor and the value from that sensor at a given time is what produces the sound. Think of it as if you had a piano. If the temperature is 57° then the 57th key on the keyboard would be pressed. Or if the pH level were 8.1, then a volume knob would be rotated to 81%.

Listen to "Buoy Music" here:

|

boredomresearch

Vicky Isley & Paul Smith

Robots in Distress is a simulation of autonomous underwater agents, developed in collaboration with the Artificial Life Lab (Karl Franzens University, Graz Austria), who are creating the world's largest underwater robot swarm to monitor the heavily human-polluted Venice Lagoon. In this artwork boredomresearch present a murky underwater world populated by glowing craft navigating the hazards of plastic waste. The SciArt collaboration ponders the nexus of biology, robotics, and environmental impact by confronting the emergence of synthetic emotions in challenging environmental circumstances; these craft are learning to recognize and express hopelessness. This expression of emotional robotics inquires on the relationship between organism and its environment in a context of increased dependence on advanced technological solutions.

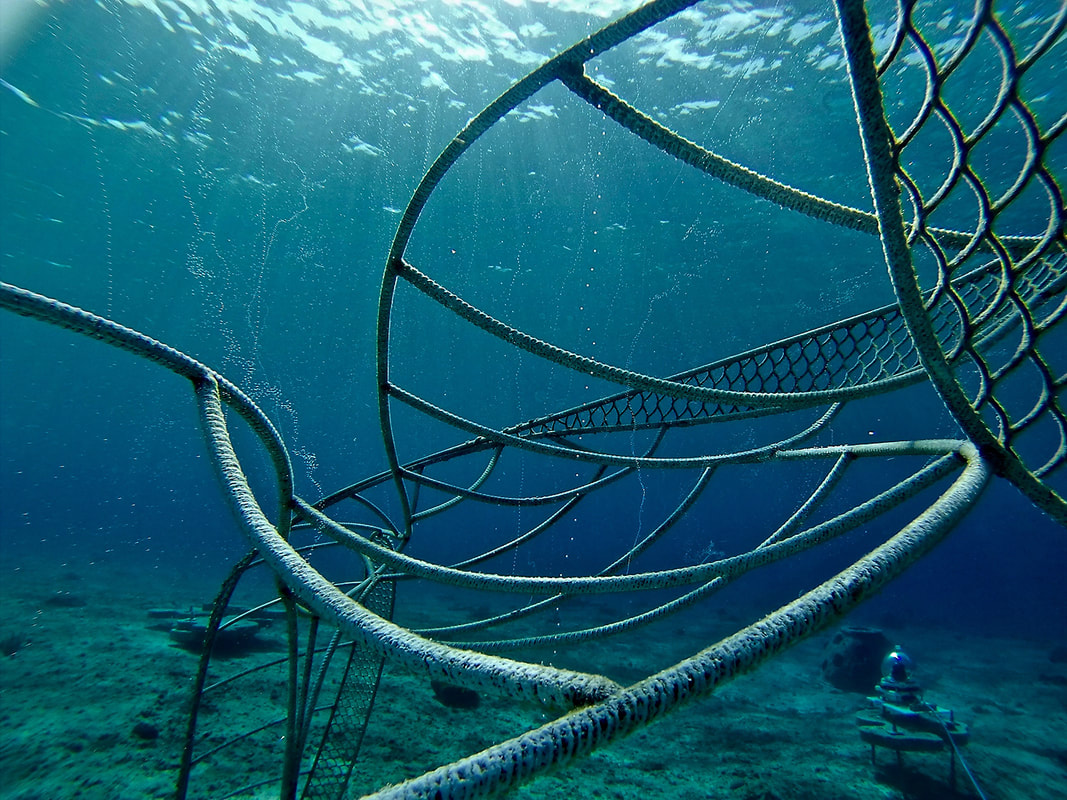

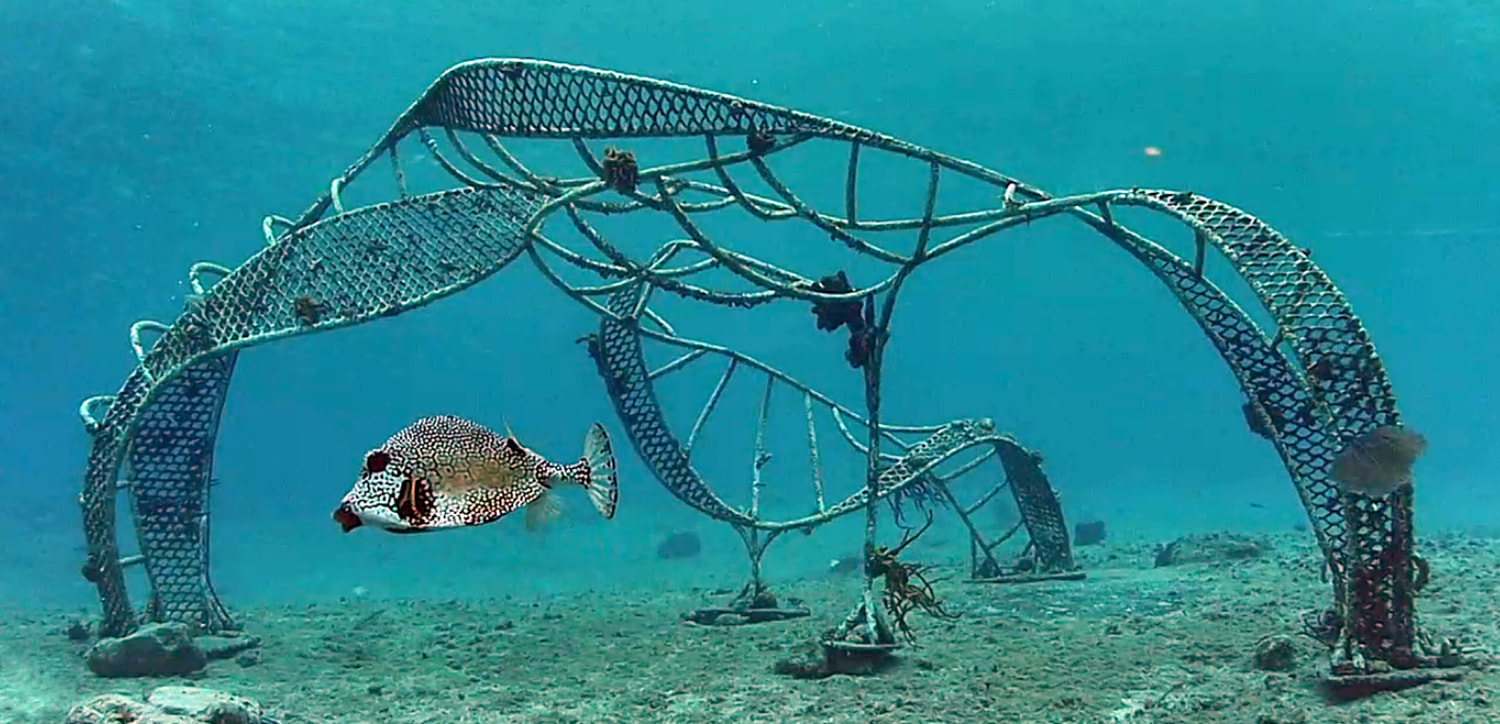

COLLEEN FLANIGAN

Zoe means “life” in Greek, and my eponymous project is a memorial to Zoe Anderson, a young woman who wanted to save corals, and who tragically died from carbon monoxide poisoning. It's a sad irony that carbon monoxide's sister molecule, carbon dioxide, is threatening our entire planet. This "living sea sculpture" Zoe is installed in Cozumel, Mexico, and disseminated worldwide through a virtual aquarium - the Zoecam - livestreaming 24/7. Low voltage electricity precipitates minerals to fortify the sculpture to become an evolving, life supporting habitat for homeless corals and biodiversity in a region devastated by hurricanes, pollution, tourism, and climate change. As a memorial and coral refuge, this project uses the power of art, science, and technology to highlight life’s fragility and its promise. Nothing happens in a vacuum. If the ocean teaches us anything, it’s that everything is connected and we belong to the same planet. It’s our job to create the conditions for life to flourish.

Watch the livestream of "Zoecam" here:

DAVID HARRIS & SEAN PACE & ZACH CORSE

When a catastrophic earthquake occurred off the coast of San Francisco on April 18, 1906, most of San Francisco was destroyed and the shaking was felt for hundreds of miles. The effects of the earthquake were captured in photos and print journalism but a visceral sense of the movement is lost in time. This piece re-creates the earthquake's physical motion in a six minute water vibrafication of the 1906 earthquake data, corresponding to the real-time shaking.

The earthquake’s motions are represented by water vibrations in a custom-built cymatic water table. The often-violent intensity of water disturbances correspond to the strength of ground vibrations as reconstructed by a U.S. Geological Survey analysis. The rising and falling of the intensity over time, seen, heard, and felt give a sense of the unknowingness experienced by San Francisco inhabitants as the shaking would subside, only to resume with great ferocity.

The earthquake’s motions are represented by water vibrations in a custom-built cymatic water table. The often-violent intensity of water disturbances correspond to the strength of ground vibrations as reconstructed by a U.S. Geological Survey analysis. The rising and falling of the intensity over time, seen, heard, and felt give a sense of the unknowingness experienced by San Francisco inhabitants as the shaking would subside, only to resume with great ferocity.

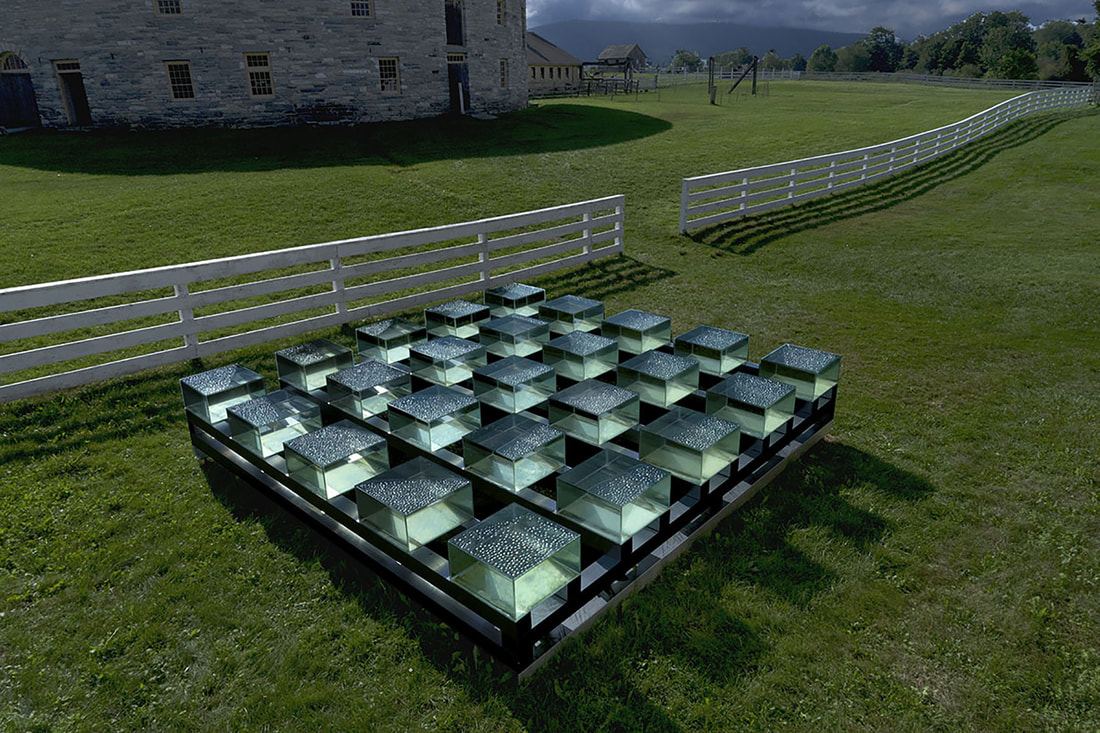

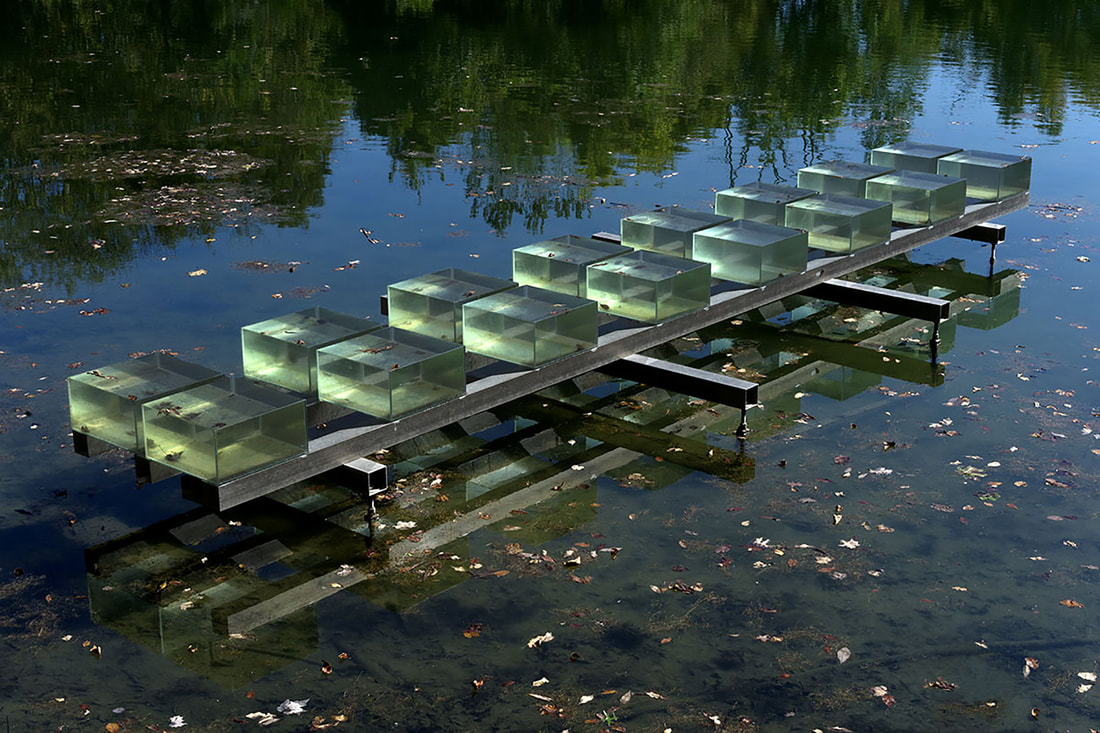

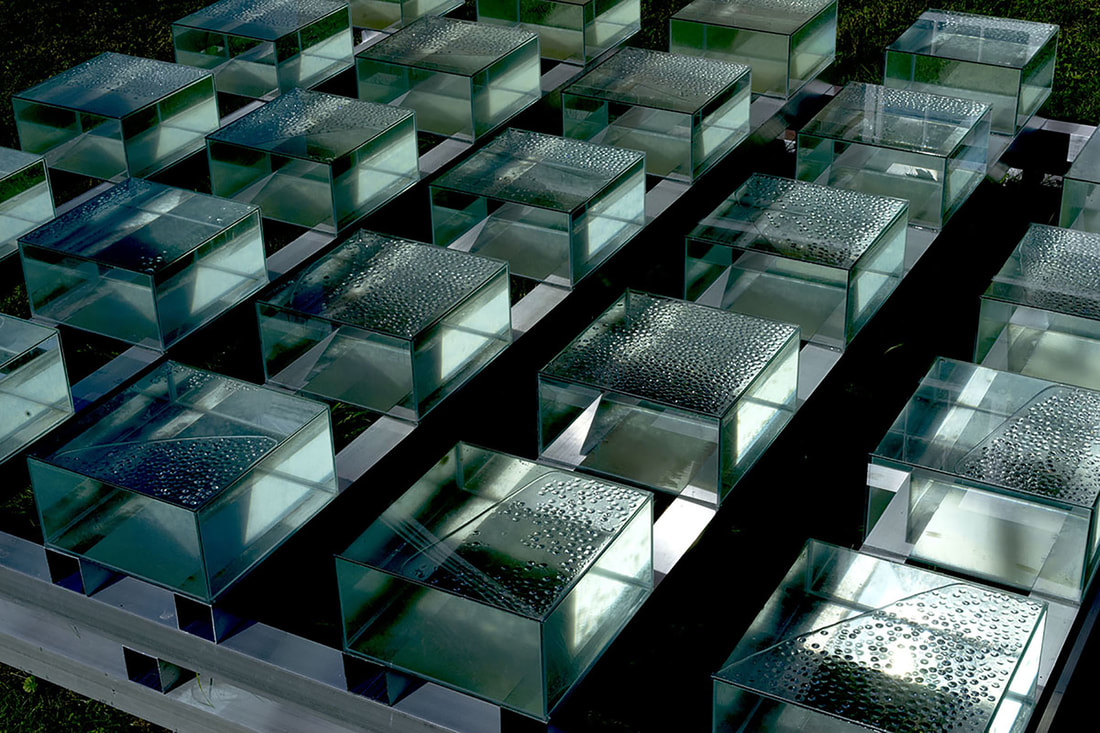

DAVID TEEPLE

My work centers on the topic of water: as a subject, a material, and an idea. From sculptures that hold water to installations that rest on the surface of water, I strive for the ephemeral and perceptually mysterious.

In an ongoing series of environmental installations, I have placed water-filled glass tanks in various contexts: for instance, on a river where the tanks appear to be floating on the surface, or under a skylight in a long narrow room. Utilizing Snell’s law of refraction, the works challenge the relationship between perception and interpretation and how we interact with place. Part ritual, part experiment, part conceptual and aesthetic art action, the installations absorb and reconfigure both the surrounding imagery and the structure of the sculpture itself, creating visual phenomena that extend beyond the parameters of water and glass.

It is poetry. A field of water-filled glass tanks, both a sculpture and a living painting, slowly yet constantly changes, speaking to impermanence. Over time, things may form in these tanks such as bubbles, condensation droplets, or water from rain on the surface. In some works, capillary action pulls rain with its impurities over the edge and into the tank, with each tank becoming a separate ecosystem. Each tank is reflected in and refracted by its neighboring tanks, creating a kaleidoscopic visual field, while also

drawing in the surrounding architecture and landscape. A spare repetitive pattern - but nothing really repeats in repetition; each unit is unique. Introducing water into a field of glass structures amplifies our perception of the geometric field itself as well as the environment in which it sits.

If systems thinking is described as the relationship of separate components to a complex structure, across disciplines, the sculptures specific combination of materials may be a window into a larger organizational code of patterns. How is the whole affected by its constituent parts? In this context, the course of my practice is an inquiry that looks at water for an organic pathway toward a broader yet more refined meaning.

In an ongoing series of environmental installations, I have placed water-filled glass tanks in various contexts: for instance, on a river where the tanks appear to be floating on the surface, or under a skylight in a long narrow room. Utilizing Snell’s law of refraction, the works challenge the relationship between perception and interpretation and how we interact with place. Part ritual, part experiment, part conceptual and aesthetic art action, the installations absorb and reconfigure both the surrounding imagery and the structure of the sculpture itself, creating visual phenomena that extend beyond the parameters of water and glass.

It is poetry. A field of water-filled glass tanks, both a sculpture and a living painting, slowly yet constantly changes, speaking to impermanence. Over time, things may form in these tanks such as bubbles, condensation droplets, or water from rain on the surface. In some works, capillary action pulls rain with its impurities over the edge and into the tank, with each tank becoming a separate ecosystem. Each tank is reflected in and refracted by its neighboring tanks, creating a kaleidoscopic visual field, while also

drawing in the surrounding architecture and landscape. A spare repetitive pattern - but nothing really repeats in repetition; each unit is unique. Introducing water into a field of glass structures amplifies our perception of the geometric field itself as well as the environment in which it sits.

If systems thinking is described as the relationship of separate components to a complex structure, across disciplines, the sculptures specific combination of materials may be a window into a larger organizational code of patterns. How is the whole affected by its constituent parts? In this context, the course of my practice is an inquiry that looks at water for an organic pathway toward a broader yet more refined meaning.

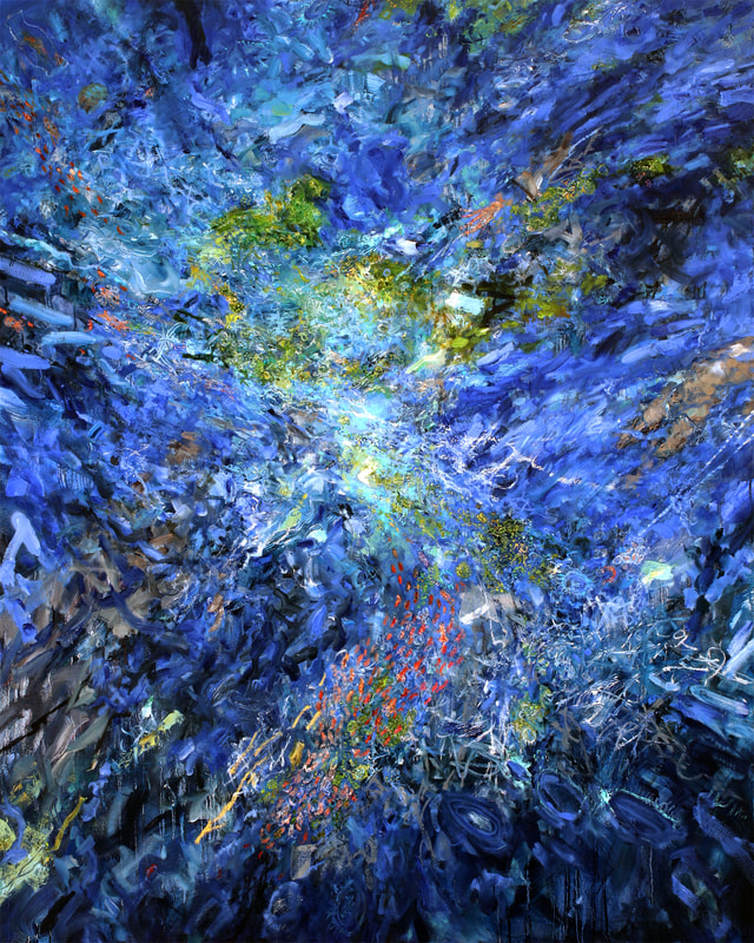

JOYCE YAMADA

Those of us who are scientifically aware know that we are unraveling the webs of life that support us; in my current "Ocean Series" I cannot help but reflect this knowledge, but I hope also to inspire awe, wonder, and joy at the complex and beautiful world in which we live. We depend upon our explorers to bring us visual footage and scientific knowledge about the oceans. It is important to support this research and this visual recording; we will not save what we do not love. I have spent hours staring at the videos now becoming available. Each of the paintings submitted has relied on such research and several are additionally inspired by poetry.

JULIA KROLIK & OWEN FERNLEY

Depth to Water is a code-based work that uses 367,089 private-well water data points to map the geography of Ontario, Canada. It also displays the depth at which water was found for each well at a 100-meter scale revealing a slice-view of the aquifer.

Artist Statement

Thousands of points form recognizable territories thereby connecting the viewer to familiar places. As regions pass across the screen, each dot transforms into a single unearthing of water. Depth to Water places emphasis on groundwater as one continuous subterranean resource, no longer assigned to a temporal scale and summed up by a myriad of water discoveries. While most residents rely on municipal water sources (as evidenced by a lack of data points near larger cities), a subset depend on groundwater wells. When wells are depicted as a perforated sheet transitioning over a watercolor canvas, the extent and scope of our groundwater use is revealed. As Benjamin Franklin once said: “When the well’s dry, we know the worth of water.”

Science Statement

Depth to Water displays a subset of the Ontario Water Well Information System Access Database (WWIS). The display is partitioned into two sections. The upper section displays the position of wells in decimal degrees, while the lower section displays 100 meters of depth as each well intersects the middle boundary. Wells deeper than 100 meters are displayed, but continue off the screen. Municipal locations of interest were geocoded and added as spatial reference points. The algorithm displaying the data uses MySQL to query the well and city databases. The program is rendered in HTML5 canvas. The colors and texture were created using watercolor and specialized paper.

Artist Statement

Thousands of points form recognizable territories thereby connecting the viewer to familiar places. As regions pass across the screen, each dot transforms into a single unearthing of water. Depth to Water places emphasis on groundwater as one continuous subterranean resource, no longer assigned to a temporal scale and summed up by a myriad of water discoveries. While most residents rely on municipal water sources (as evidenced by a lack of data points near larger cities), a subset depend on groundwater wells. When wells are depicted as a perforated sheet transitioning over a watercolor canvas, the extent and scope of our groundwater use is revealed. As Benjamin Franklin once said: “When the well’s dry, we know the worth of water.”

Science Statement

Depth to Water displays a subset of the Ontario Water Well Information System Access Database (WWIS). The display is partitioned into two sections. The upper section displays the position of wells in decimal degrees, while the lower section displays 100 meters of depth as each well intersects the middle boundary. Wells deeper than 100 meters are displayed, but continue off the screen. Municipal locations of interest were geocoded and added as spatial reference points. The algorithm displaying the data uses MySQL to query the well and city databases. The program is rendered in HTML5 canvas. The colors and texture were created using watercolor and specialized paper.

KATE SCHWARTING

Radiolarians and Diatoms is one of a series of pen and ink drawings drawn under magnification using a loop or hand lens. It depicts hundreds of diatoms and radiolarians arranged to form rock strata. When the organisms die and and settle out of the water column, some are preserved and later found as fossils. What it would be like to see all of the radiolarians and diatoms that go into making rock strata including those that don't survive the fossilization process. These strata have been folded and faulted and are at odd angles. The goal is to use these micro compositions within the larger macro compositions to draw attention to these organisms and the processes that affect them, processes which have a large impact on our environment as well as on our understanding of past climate change. The strata and fossils represent a “written” record of past ocean ecosystems and climate. Fossils pictured are mixtures of real and hybrid organisms and represent both the extraordinary structures and variety as well as the limits of what we know and potential existence of undiscovered organisms.

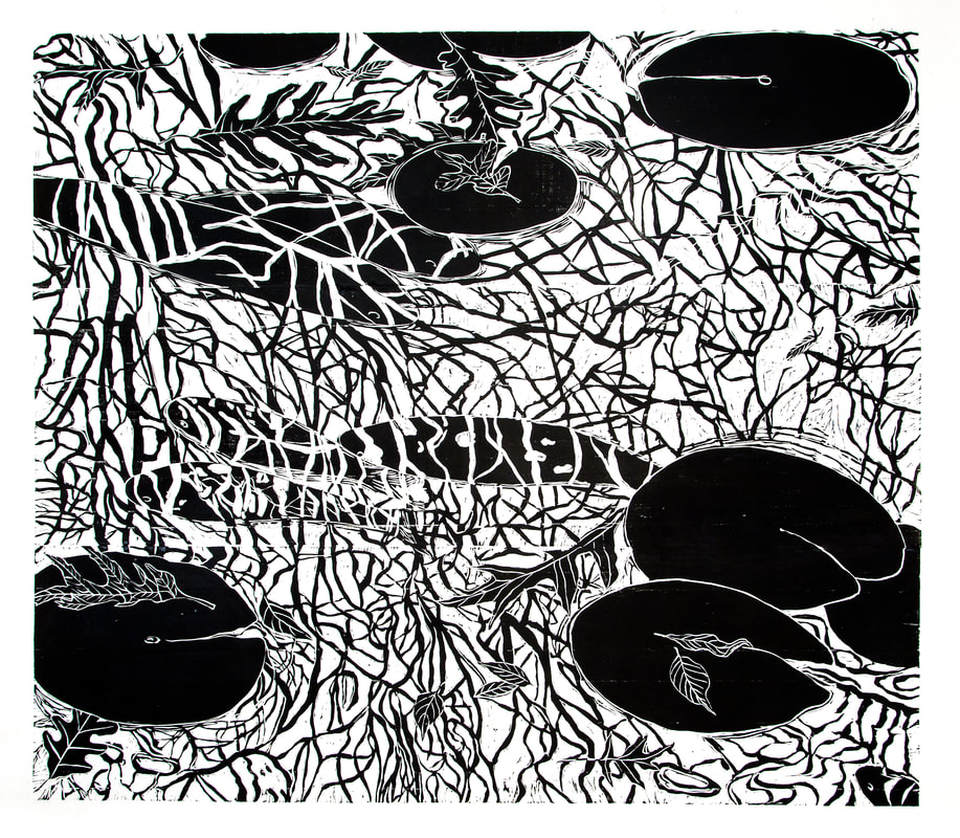

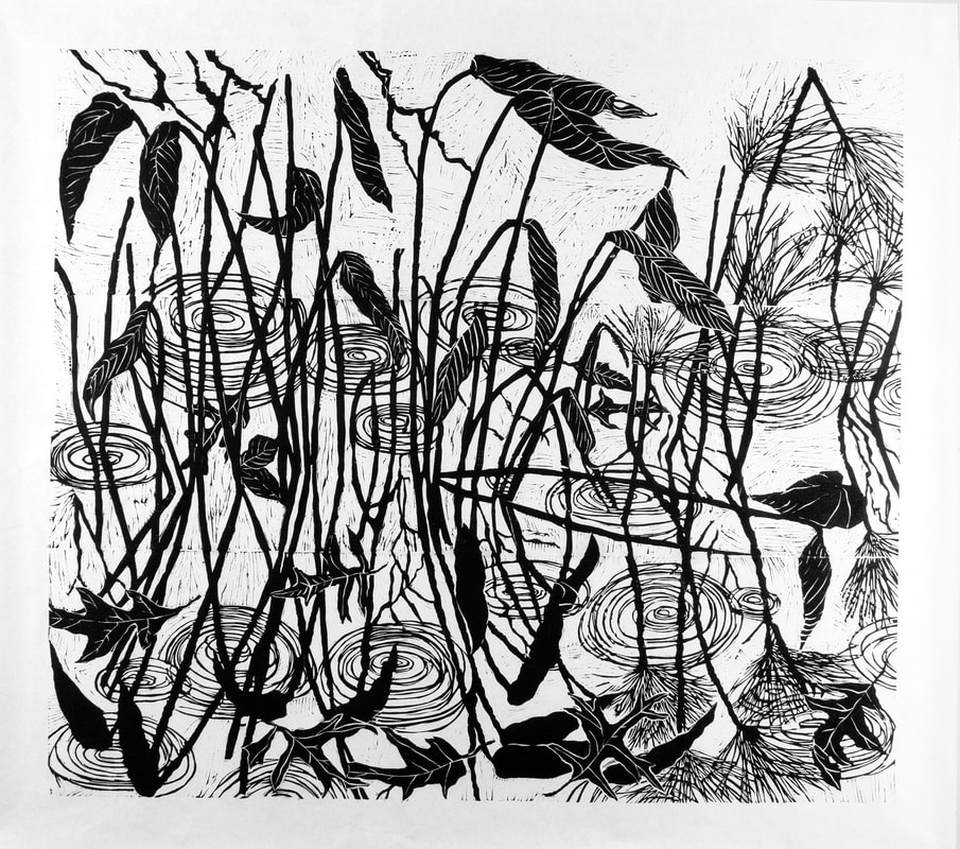

KRISTIN HARRIS

Reflections of plants in water has been common subject matter in my artwork. The art of China and Japan and the aesthetic of simplicity and beauty in nature have been great inspirations. Woodcuts offer both visual strength and delicacy. I work from simple pencil line drawings on the wood, not really knowing what to expect when the work is reversed in printing.

LAURA FERGUSON

The water in our bodies, like the fluid milieu interieur that bathes our 75 trillion cells, is our primeval connection to the oceans and seas and the origins of life. I’m an artist whose work is all about the body (my own body, drawn from the inside out), and its connection to the processes and patterns of nature. My images are literally created by water itself, and imbued with its dynamics of movement, fluidity and flow, through my “floating colors” art-making process. I drop thinned oil paints onto the surface of a tray of water, where they spread out and open to reveal their inner structure as if magnified under a microscope lens. Like winds and tides, in a microcosm of the natural world, their patterns of movement arise from a complex interplay between the thickness of the water, the temperature and humidity of the air, and the chemistry of individual pigments. The images that form are transferred to paper and become the foundation for drawings or for prints in which I layer drawing with photomicrographs or medical images. My access to the details and textures of human anatomy comes from my role as Artist-in-Residence at NYU School of Medicine, where I draw from bones and cadaver dissections and from my own 3D radiology scans.

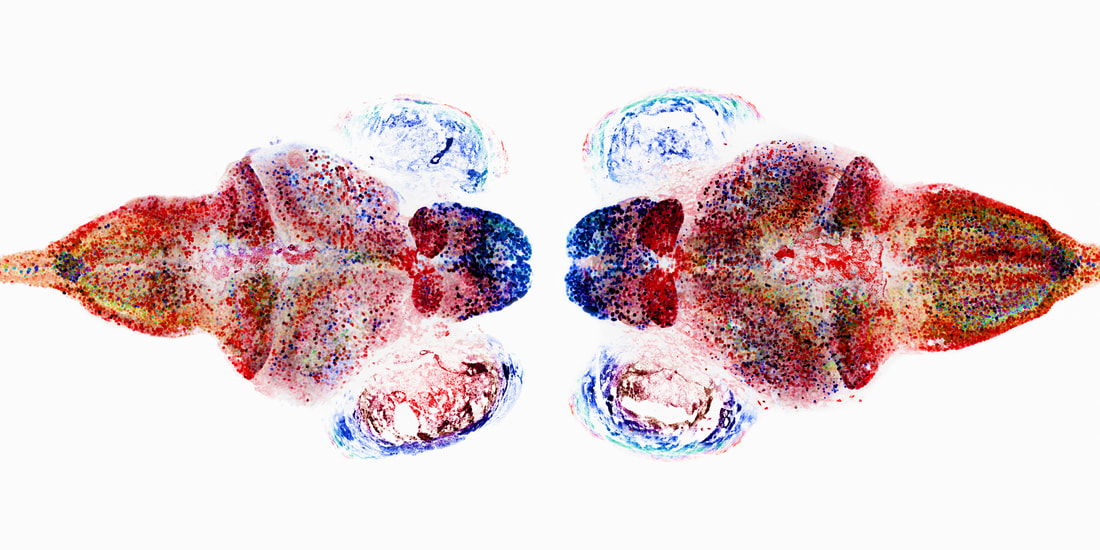

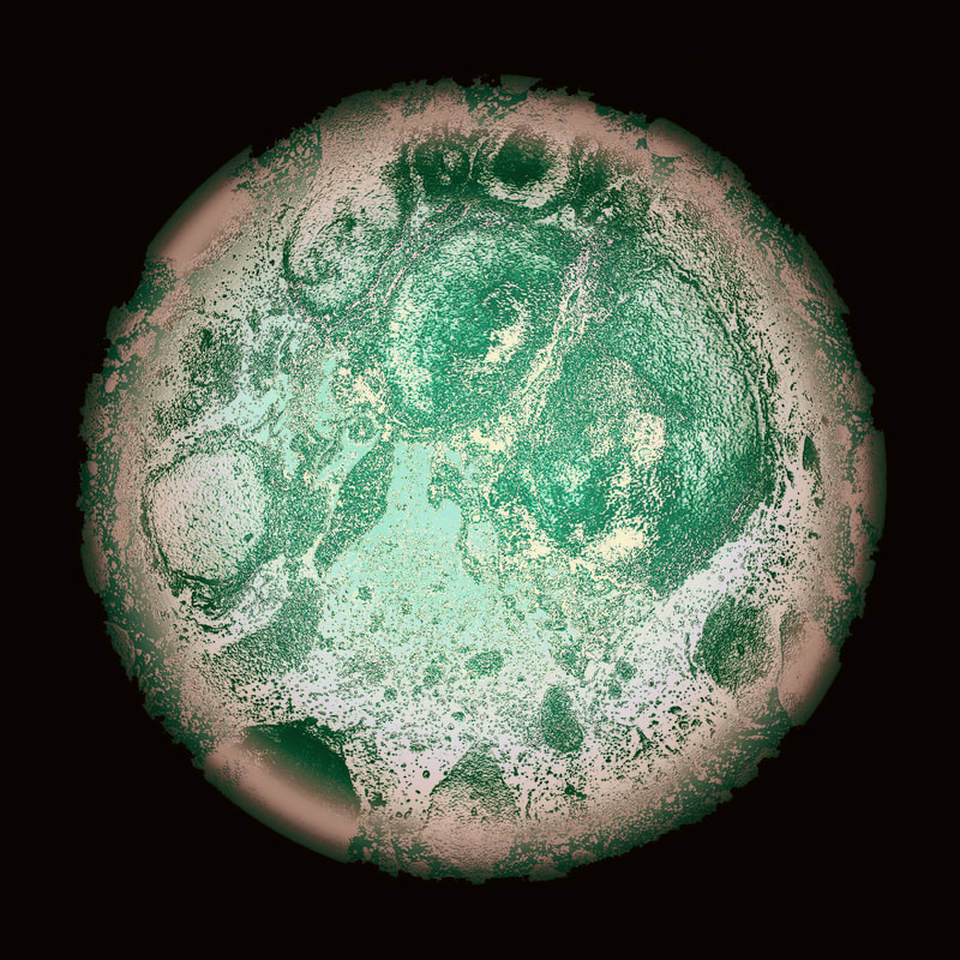

LUKE MANINOV HAMMOND

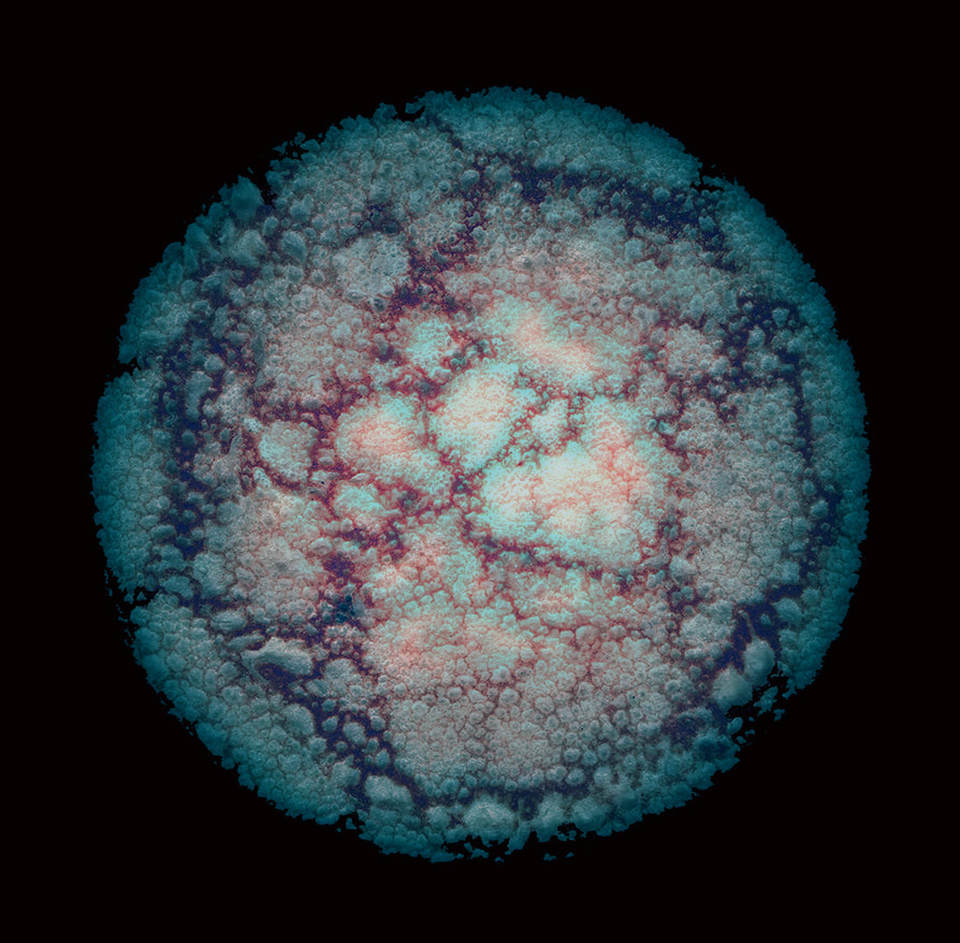

Inspired by my continuing work in biomedical imaging and neuroscience research, my practice is focused on reimagining biological forms to explore themes of impermanence, consciousness, and the connection between all living things.

Our exploration of the sea has enabled us to illuminate the living brain and journey inwards, revealing previously unknown worlds of hidden beauty within us. These images explore our ability to make the invisible visible in biomedical imaging using glowing proteins originally discovered in jellyfish.

Our exploration of the sea has enabled us to illuminate the living brain and journey inwards, revealing previously unknown worlds of hidden beauty within us. These images explore our ability to make the invisible visible in biomedical imaging using glowing proteins originally discovered in jellyfish.

"Observing Vision." Created in collaboration with Dr. Jeremy Ullmann, Research Fellow in Neurology at Boston Children's Hospital.

Taking advantage of the transparent skin of the zebrafish we were able to image and observe individual neurons within the living brain. Many gigabytes of individual images were captured and reconstructed to produce the images of the fish shown here. These images were captured at high-resolution in 3D using state-of-the-art fluorescence microscopy at the University of Queensland's, Queensland Brain Institute.

Taking advantage of the transparent skin of the zebrafish we were able to image and observe individual neurons within the living brain. Many gigabytes of individual images were captured and reconstructed to produce the images of the fish shown here. These images were captured at high-resolution in 3D using state-of-the-art fluorescence microscopy at the University of Queensland's, Queensland Brain Institute.

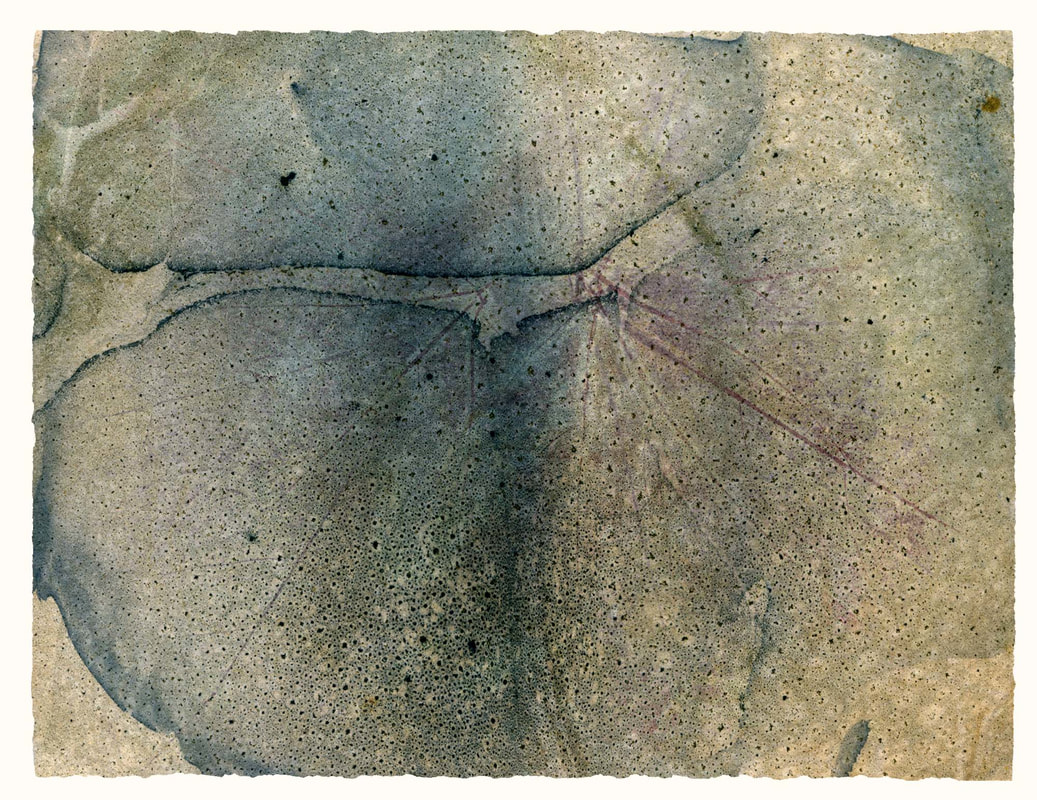

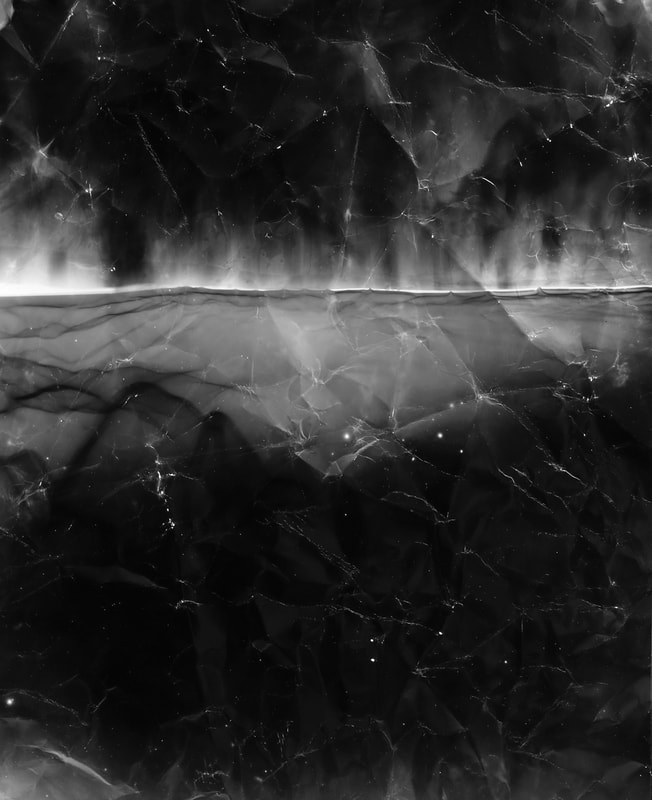

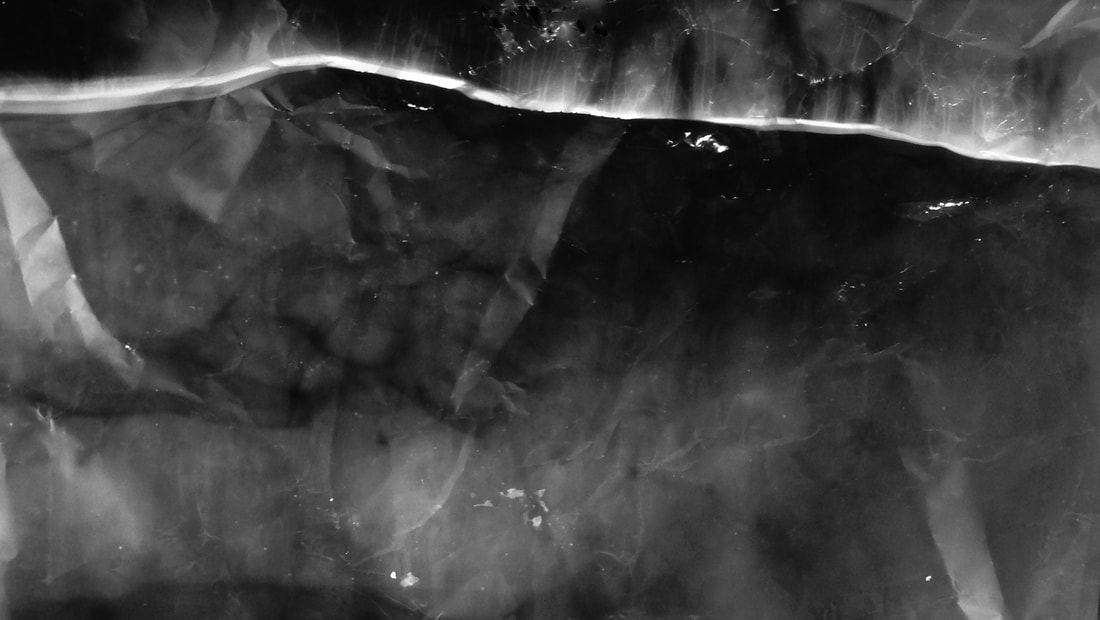

MICHAEL FLOMEN

The unique photograms seen here are portraits of lake water made in Northern Quebec. I make photographs of things we do not see but know are there. I have been making photographs with all forms of water found in nature in all four distinct seasons in the North East. I am interested in picturing unknown worlds.

NINA YANKOWITZ

Since the year 2000, my environmental portraits have focused on exposing the current instability of earth bound trust, exploding reliance and structures into particles of dust. I like creating bridges to travel between the reel-to-real that builds the skeletal scaffoldings of memories. I create temporary, ephemeral, and/or time-based artworks and sometimes work with team contributors from across the globe. To enhance individual awareness of environmental conditions, I infuse interactive technology and social networking tools into sculptural elements at various sites.

During 2004-2005 I created CloudHouse. It is a variable-sized glass and aluminum house structure, imagined as a soothsayer, warning the public about an upcoming onslaught of inclement, destructive, weather conditions. The modified greenhouse structure contains a

cloud continually in process of changing shapes. An ultrasound generator dispels fine droplets of mist and the size and density of the cloud formations are determined by the external barometric pressure conditions surrounding the house.

During 2004-2005 I created CloudHouse. It is a variable-sized glass and aluminum house structure, imagined as a soothsayer, warning the public about an upcoming onslaught of inclement, destructive, weather conditions. The modified greenhouse structure contains a

cloud continually in process of changing shapes. An ultrasound generator dispels fine droplets of mist and the size and density of the cloud formations are determined by the external barometric pressure conditions surrounding the house.

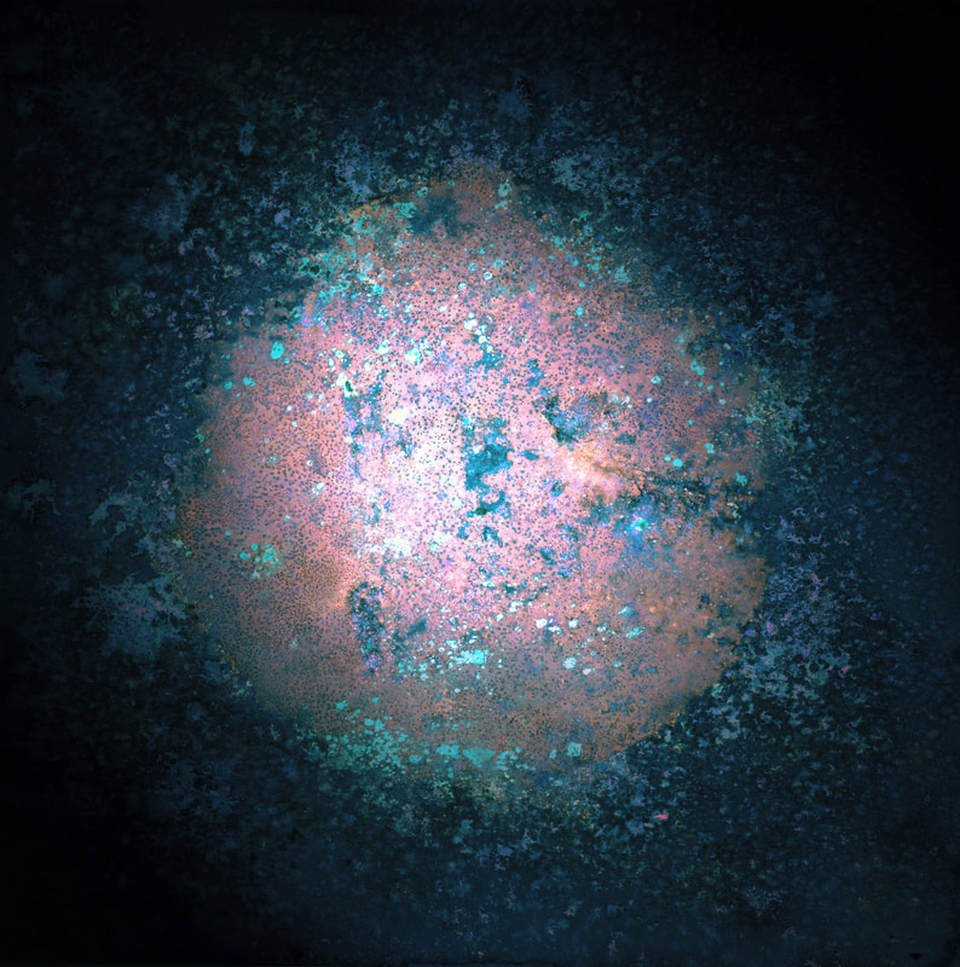

PAMELA BAIN

Largely scrutinizing relationships between inner and outer worlds - their hidden secrets and visual revelations - my work draws upon organic shapes and patinas pertaining to the body and to the environment both near and cosmically far. In so doing I observe that we and the universe share a mutual composition and that we, as human entities, search for meaning within that which is concealed and upon which we exert hypotheses.

My series "Water World" has a cosmic connection to water which evolved after learning about a NASA research project that is looking for evidence of life on Mars by searching its terrain for past evidence of stromatalites. On Earth, these structures are water-based living systems and examples of the earliest known life forms. The microbes of stromatalites now found in the hypersaline waters of the Bahamas and Shark Bay Western Australia are similar to organisms that existed 3.5 billion years ago. NASA is mapping these structures at Shark Bay in order to compare their configurations to the landscape of Mars. A positive match would add to the body of evidence that life existed on the planet.

My series "Water World" has a cosmic connection to water which evolved after learning about a NASA research project that is looking for evidence of life on Mars by searching its terrain for past evidence of stromatalites. On Earth, these structures are water-based living systems and examples of the earliest known life forms. The microbes of stromatalites now found in the hypersaline waters of the Bahamas and Shark Bay Western Australia are similar to organisms that existed 3.5 billion years ago. NASA is mapping these structures at Shark Bay in order to compare their configurations to the landscape of Mars. A positive match would add to the body of evidence that life existed on the planet.

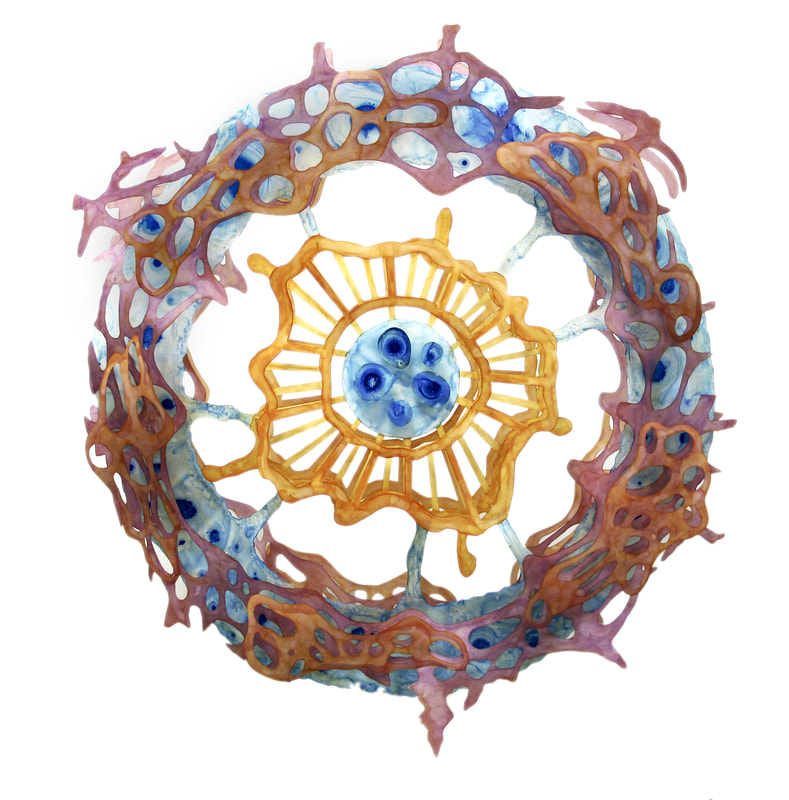

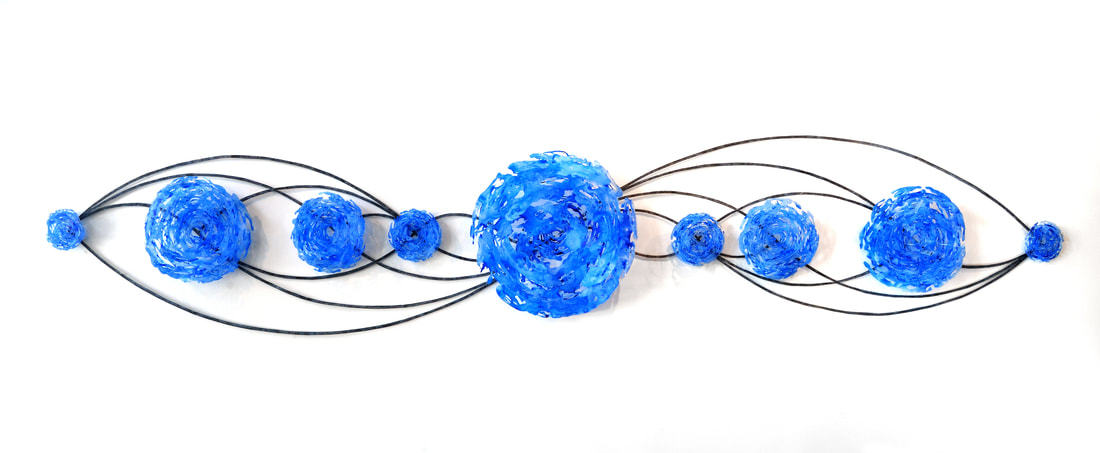

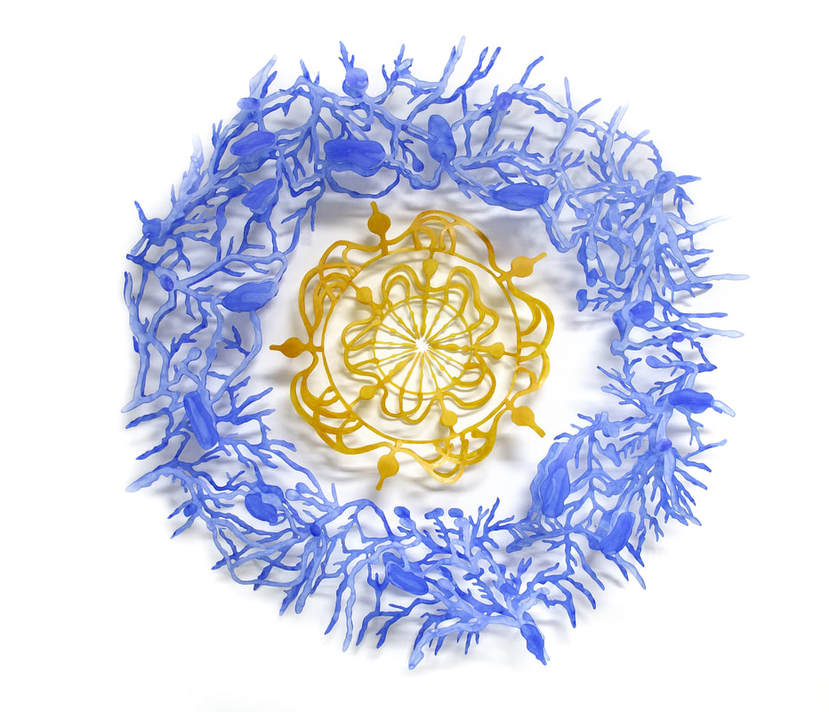

REBECCA KAMEN

Cellular Dialogue explores how water and cells create a dialogue between man and the ocean. The small circular form in the center represents the significance of water in the cell, and is surrounded by yellow radiating lines referencing the cell’s actin cytoskeleton. The larger blue circle symbolizes the ocean, home to cellular organisms such as radiolarians, expressed through cutout shapes suspended above the circle. Blue acrylic paint applied as a stain, references Nissl, a dye solution used in specimen preparation to make the invisible, visible.

The Measure of All Things explores Sacred Geometry as a visual mapping system for the human body, portrayed by two large wave- shaped forms. This geometric waveform also maps a harmonic in music, referencing how mathematics creates a language between man and all things in nature. The smaller blue circular forms symbolize the relationship of water in the body and its connection to larger bodies of water in nature (symbolized by larger circle in the center).

Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s drawings of the retina provide a seed of inspiration for Illumination. The sculpture not only celebrates Cajal’s research, but how his beautifully drawn observations continue to “illuminate” new ways of seeing. One example is the brains ability to connect visual and metaphorical patterns, revealed in the complexity of Illumination’s circular, blue outer forms. Informed by Athanasius Kircher’s, engravings of the movement of earth’s water, the sculpture references Kircher’s observations about the “secret motions” of the water of the oceans, as well as alludes to the visual complexity and dynamics of a “sea” of rods and cones in the retina.

ROBYN ELLENBOGEN

My work is inspired by many perspectives regarding an unending and constant relationship to water from early childhood to the present. The first painting I recall making in kindergarten depicted an undersea world. The motion of water, waves, currents, and flow are present within my work. My investigations through microscopy have deepened my appreciation for water and fostered interpretations through an ongoing series of metalpoint drawings. These investigations also relate to a Shamanic-based reverence for water throughout all ancient cultures.

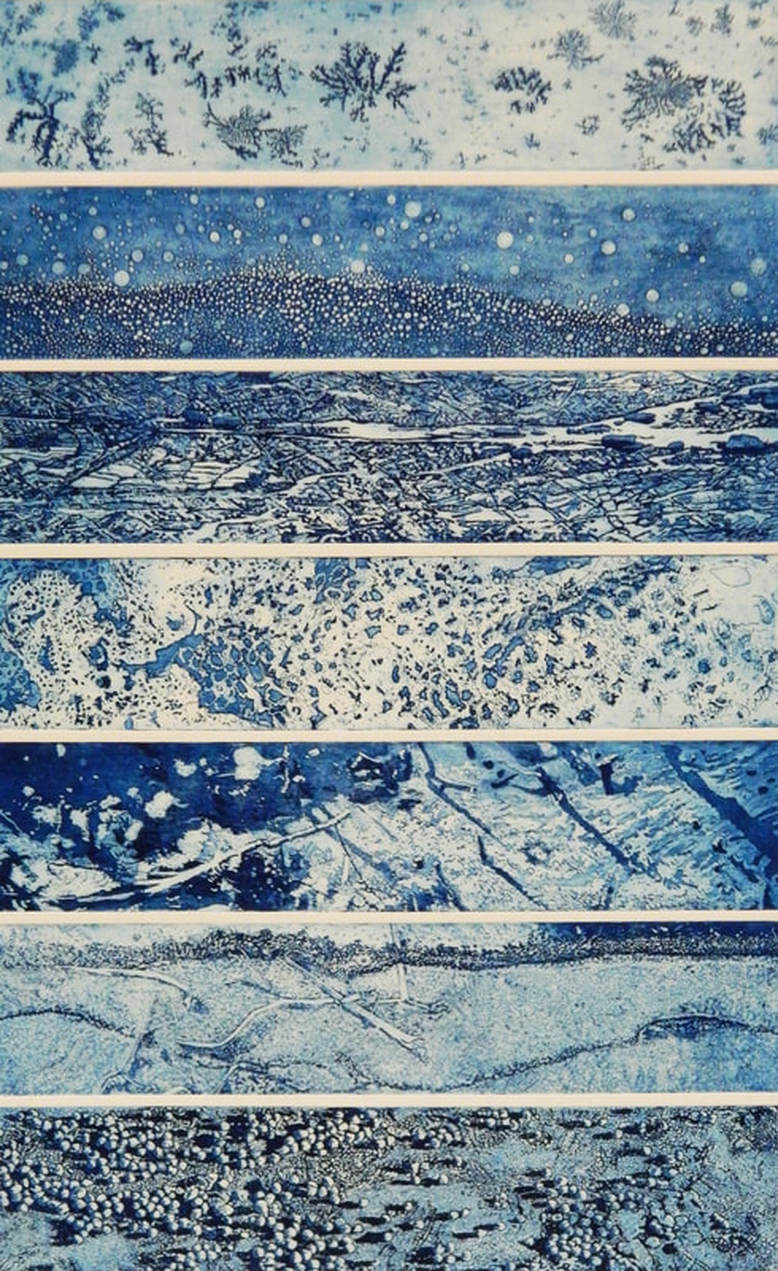

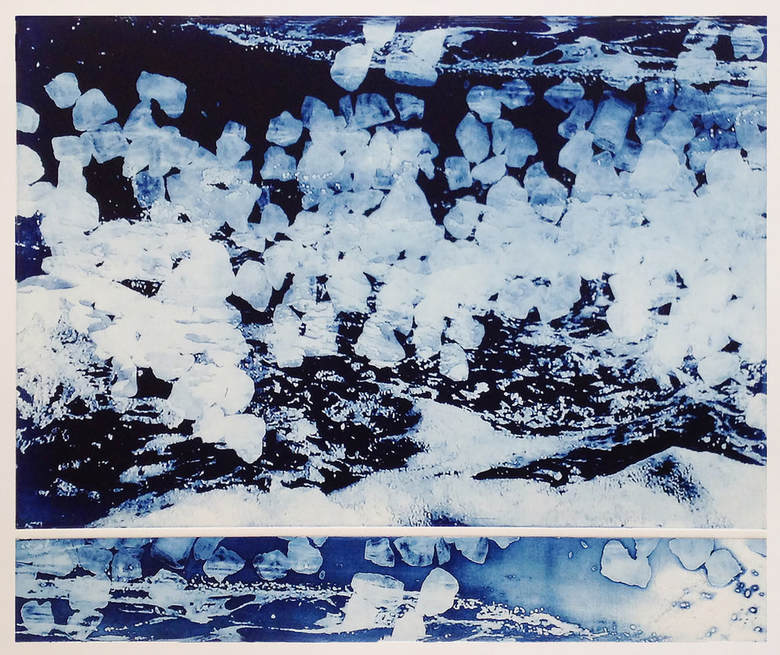

SANDRA WILLIAMS

The techniques of printmaking provide many ways to communicate ideas and develop imagery. Every aspect is intensely challenging. Working with materials and methods considered safer for the artist and the environment, my works reflect an interest in the connections and relationships observed in the world around me. I am deeply concerned about the gradual degradation of our environment, often including an oblique environmental message, but usually preferring to draw attention to the significance of nature in our lives and to celebrate its beauty.

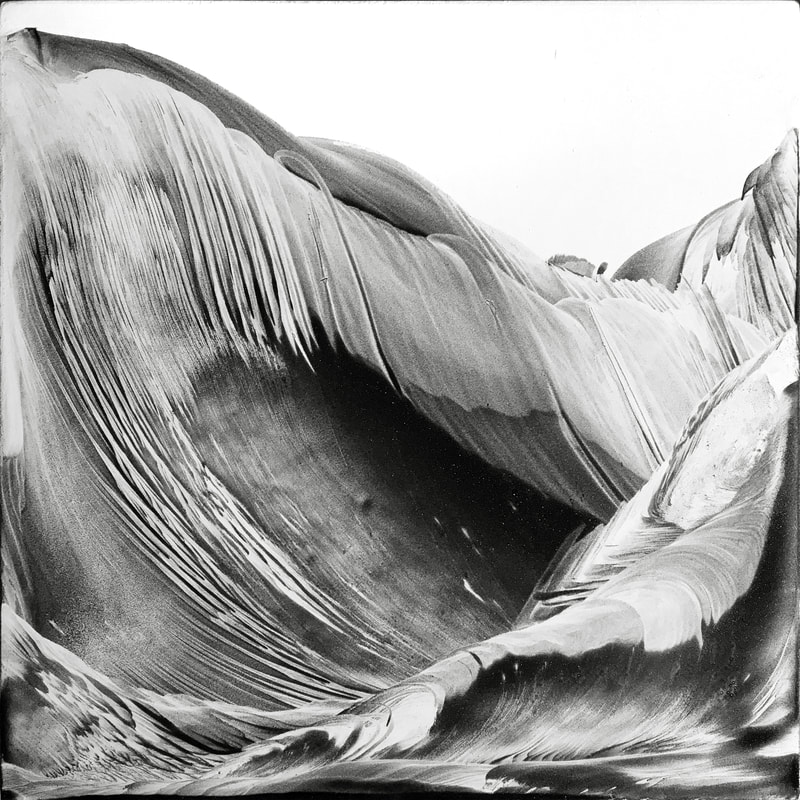

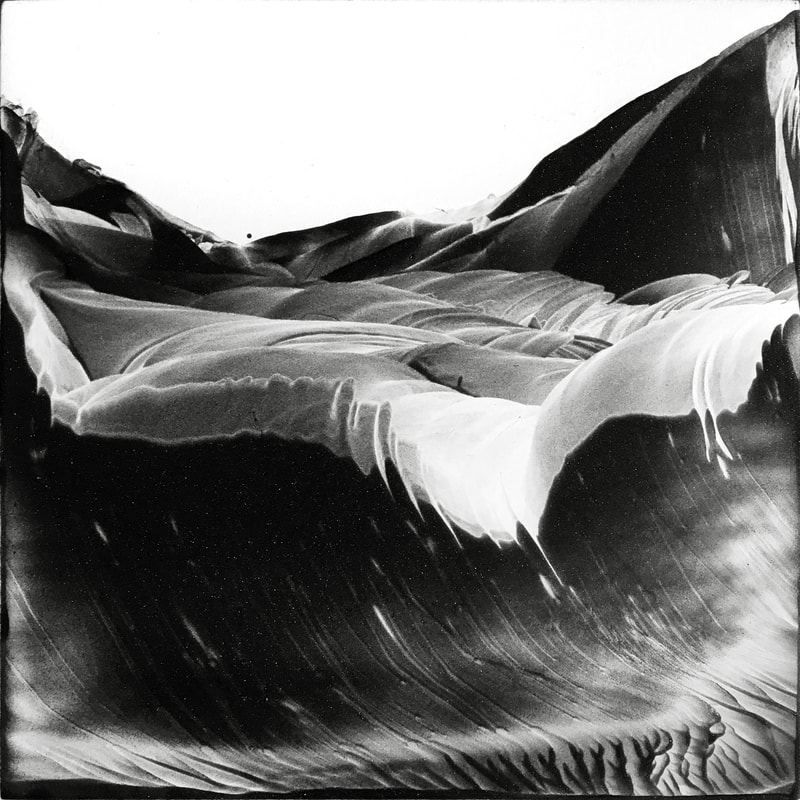

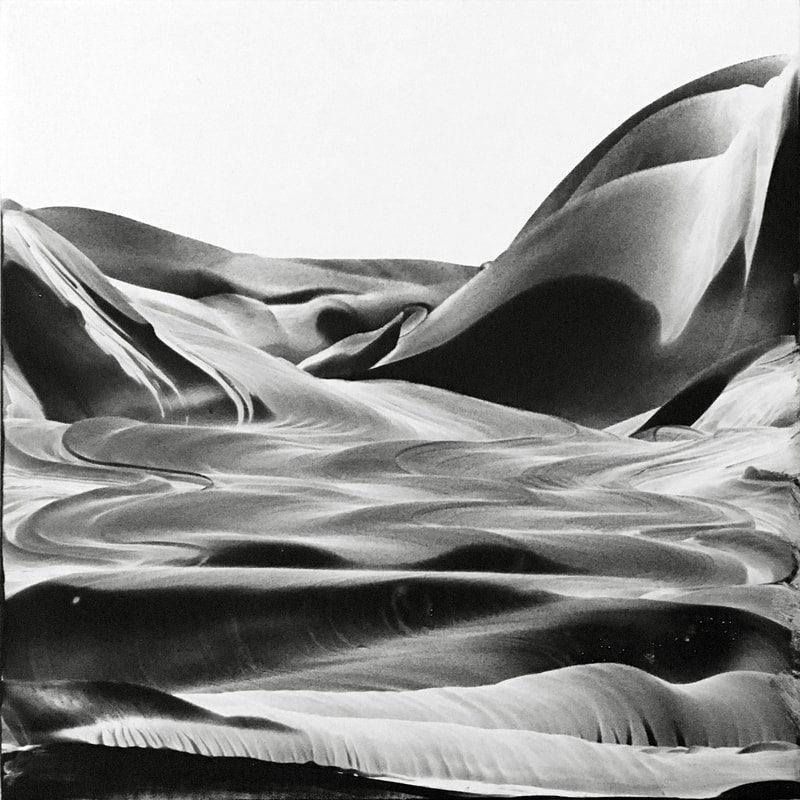

SEANA REILLY

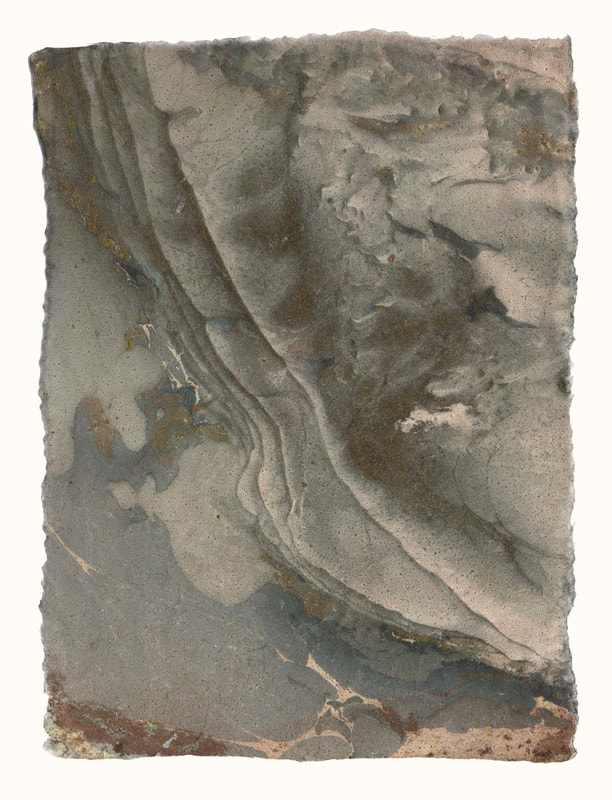

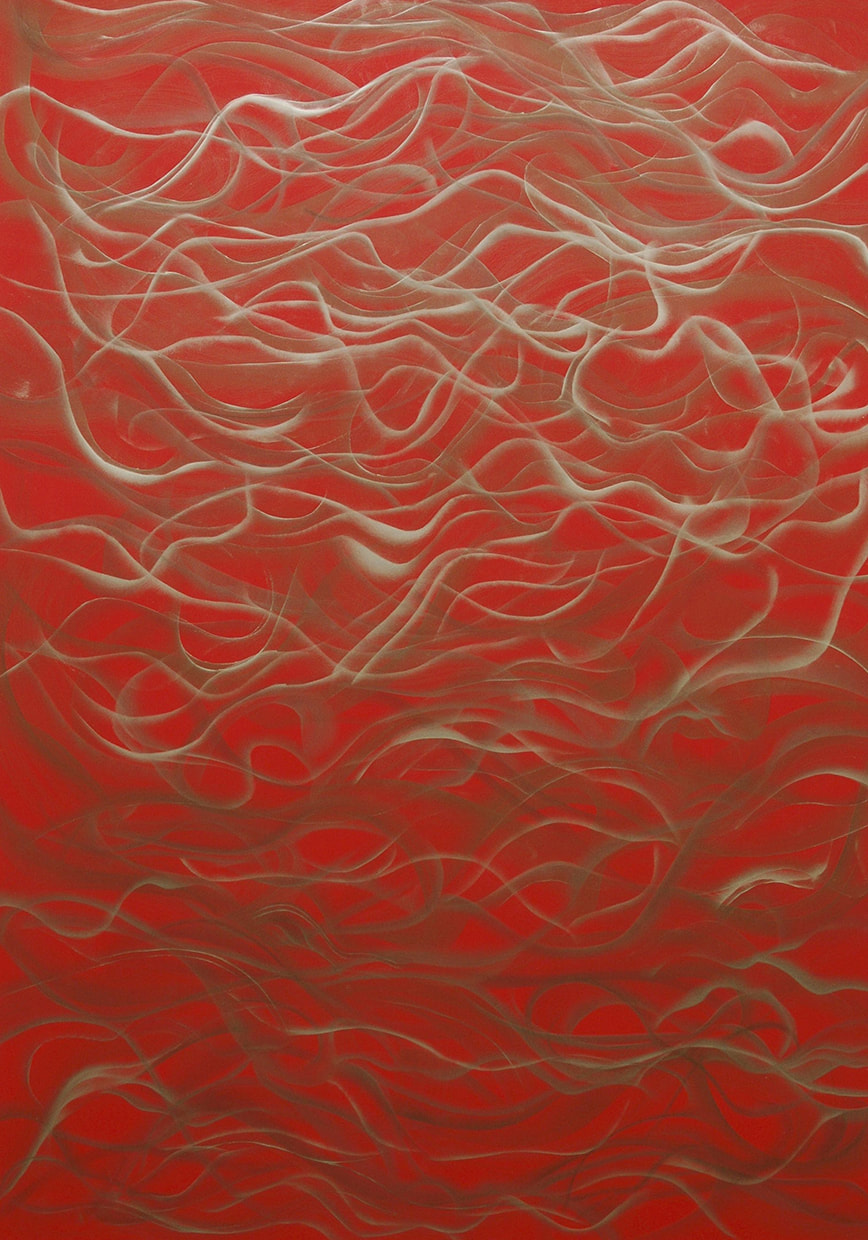

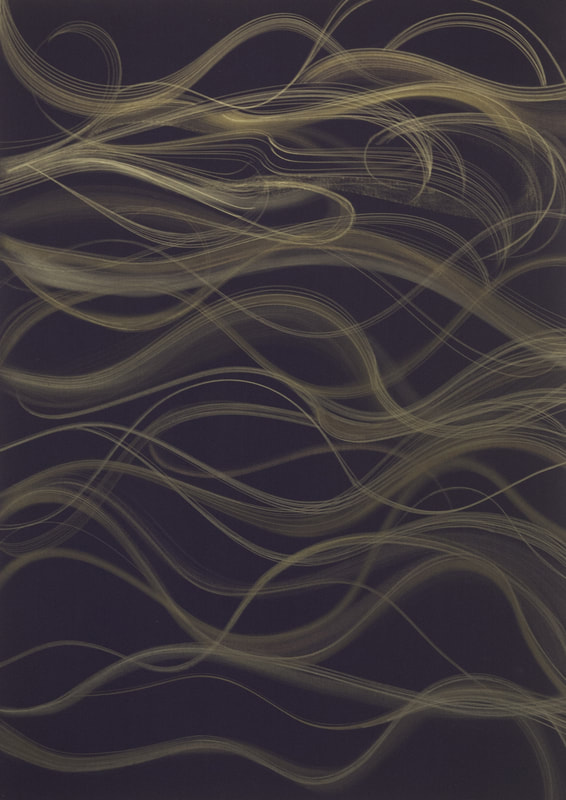

My studio practice is a communion with the movement of water and earth. By subjecting my material to the forces that drive the evolution of the the planet, I’m creating imagery that is similar to the actual patterns that move across the surface of the Earth, though on a much smaller temporal and spatial scale, one which I can hold in my hands.

My artistic process is a natural outgrowth of my lifelong interest in the earth sciences and Buddhist thought. In this series of small experimental paintings/drawings I have loosed feral tides of liquid graphite and allowed it to spread unimpeded across the surface. I did not intend to make tiny tsunamis. I set out to see what capillary action would do to this liquid. The black waves were an unintended but delightful result.

This work engages me on many levels; it is concurrently a scientific investigation fueling intellectual research, a meditative practice calming the mind and relinquishing expectation, and an artistic celebration of sheer joy and delight.

My artistic process is a natural outgrowth of my lifelong interest in the earth sciences and Buddhist thought. In this series of small experimental paintings/drawings I have loosed feral tides of liquid graphite and allowed it to spread unimpeded across the surface. I did not intend to make tiny tsunamis. I set out to see what capillary action would do to this liquid. The black waves were an unintended but delightful result.

This work engages me on many levels; it is concurrently a scientific investigation fueling intellectual research, a meditative practice calming the mind and relinquishing expectation, and an artistic celebration of sheer joy and delight.

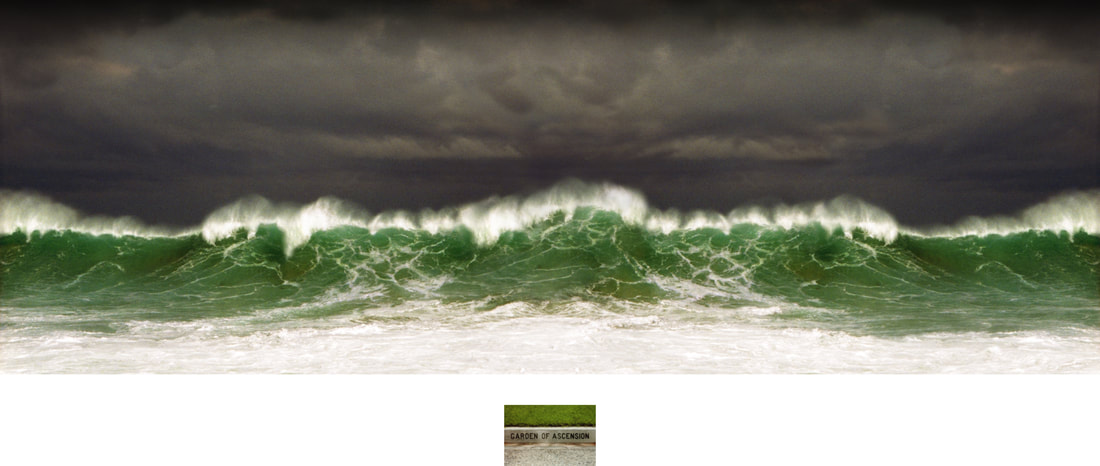

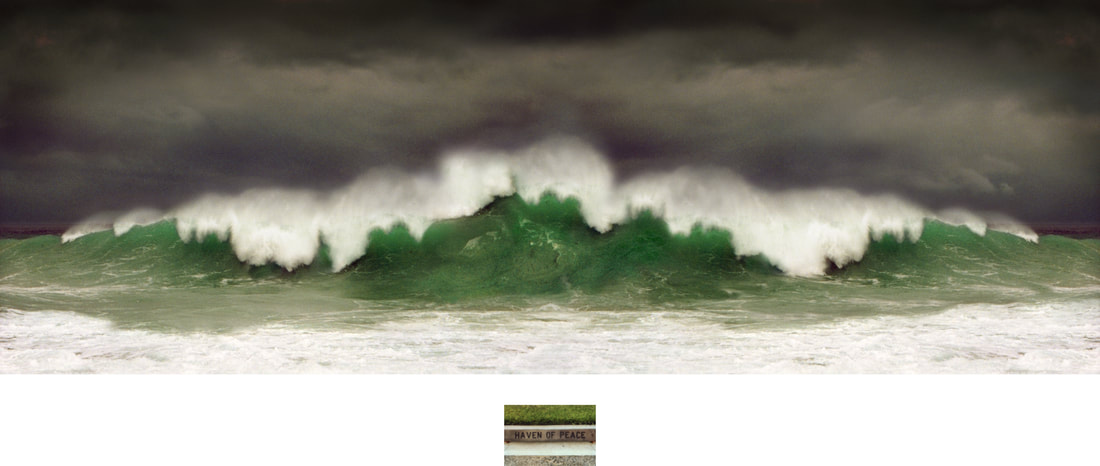

STEPHEN HILYARD

The term “king wave” refers to freak “killer” waves that appear without warning and that are many times bigger than the prevailing sea. At this time little is known about the phenomenon, scientists have only recently developed a theoretical model that allows for

such things to exist. However reports of such waves have been coming in for years, they are believed to have been responsible for the mysterious disappearance of a number of deep water vessels. During the months of March and April 2003 in Western Australia five

people were killed by king waves which swept them from the shore.

Each piece in the series consists of a pair of digital images mounted on metal panels. The larger images were made from photographs of extremely large waves that I made at Margaret River in Western Australia during the summer of 2003, a few months after the most recent king wave fatalities in the area. The smaller images in each pair are based on photographs made in cemeteries in southern California. The parenthetical title of each piece is taken from a section of the cemetery as it appears on the concrete curbstones. Both of the images have been heavily manipulated. The original wave images were mirrored to create a wide format image, all obvious evidence of this doubling was removed as the image was rebuilt. Some small clues to underlying symmetry were left at the outer edges, and the surface quality of the image was altered to suggest the feel of an oil painting. In their finished forms it's not clear whether these images are derived from the real world, or reproductions of oil paintings. The smaller images have also been subtly altered by the addition of unnaturally symmetrical elements (leaves in the gutter, joints in the concrete curbstones etc.), and artificial soft-focus. It's is my intention to present these as un-trustworthy images.

“King Wave” brings together two conflicting approaches to the big issue, the last issue, death. On the one hand there is the urge to glamorize the subject, this lies at the heart of any understanding of the sublime. Mountaineers, divers, and other adventurers can not deny that risking death whilst surrounded by the overwhelming beauty of the natural world is an important part of their motivation. Whilst this may seem to be a particularly male point of view as far as mountaineering is concerned, the same can not be said for diving, particularly free diving. Many of the world leaders in this most dangerous of sports are women, they personify the glamour of the sport in their physical beauty combined with the great risks that they take. A few days before I made the original wave photographs at Cape Naturaliste I was diving at the Ningaloo reef. While swimming with whale sharks and manta rays I pushed the limits of my own free diving abilities. Once below the surface the free diver finds herself in a floating world of incredible beauty, but there is also no doubt that she is also slowly dying every second that she is down there. I experienced this myself, and it was still fresh in my mind as I

photographed the waves.

In contrast to the sublime effect of the wave images, the second element in each of the “King Wave” pieces recognizes the sheer banality of death. This aspect of each piece speaks to the point of view not so much of those who choose to risk death, but of those left behind by it. When I first came across the list of cemetery sections as they appear in the Thomas Guide (a street map of Los Angeles) they seemed to create a poem that was both funny and tragic, in that they so plainly fail in what they are trying to do: to come to terms with death in a way that makes it seem rational, reasonable even. As well as the glamour of death “King Wave” is about all the ways that we try to deal with loss. Of course these attempts will always fail, there is no way to encapsulate death, regret and guilt in a way that lets us put it neatly away, but I found these romantic landscape descriptions stenciled on concrete curb stones poignant in their banality, and very sad.

such things to exist. However reports of such waves have been coming in for years, they are believed to have been responsible for the mysterious disappearance of a number of deep water vessels. During the months of March and April 2003 in Western Australia five

people were killed by king waves which swept them from the shore.

Each piece in the series consists of a pair of digital images mounted on metal panels. The larger images were made from photographs of extremely large waves that I made at Margaret River in Western Australia during the summer of 2003, a few months after the most recent king wave fatalities in the area. The smaller images in each pair are based on photographs made in cemeteries in southern California. The parenthetical title of each piece is taken from a section of the cemetery as it appears on the concrete curbstones. Both of the images have been heavily manipulated. The original wave images were mirrored to create a wide format image, all obvious evidence of this doubling was removed as the image was rebuilt. Some small clues to underlying symmetry were left at the outer edges, and the surface quality of the image was altered to suggest the feel of an oil painting. In their finished forms it's not clear whether these images are derived from the real world, or reproductions of oil paintings. The smaller images have also been subtly altered by the addition of unnaturally symmetrical elements (leaves in the gutter, joints in the concrete curbstones etc.), and artificial soft-focus. It's is my intention to present these as un-trustworthy images.

“King Wave” brings together two conflicting approaches to the big issue, the last issue, death. On the one hand there is the urge to glamorize the subject, this lies at the heart of any understanding of the sublime. Mountaineers, divers, and other adventurers can not deny that risking death whilst surrounded by the overwhelming beauty of the natural world is an important part of their motivation. Whilst this may seem to be a particularly male point of view as far as mountaineering is concerned, the same can not be said for diving, particularly free diving. Many of the world leaders in this most dangerous of sports are women, they personify the glamour of the sport in their physical beauty combined with the great risks that they take. A few days before I made the original wave photographs at Cape Naturaliste I was diving at the Ningaloo reef. While swimming with whale sharks and manta rays I pushed the limits of my own free diving abilities. Once below the surface the free diver finds herself in a floating world of incredible beauty, but there is also no doubt that she is also slowly dying every second that she is down there. I experienced this myself, and it was still fresh in my mind as I

photographed the waves.

In contrast to the sublime effect of the wave images, the second element in each of the “King Wave” pieces recognizes the sheer banality of death. This aspect of each piece speaks to the point of view not so much of those who choose to risk death, but of those left behind by it. When I first came across the list of cemetery sections as they appear in the Thomas Guide (a street map of Los Angeles) they seemed to create a poem that was both funny and tragic, in that they so plainly fail in what they are trying to do: to come to terms with death in a way that makes it seem rational, reasonable even. As well as the glamour of death “King Wave” is about all the ways that we try to deal with loss. Of course these attempts will always fail, there is no way to encapsulate death, regret and guilt in a way that lets us put it neatly away, but I found these romantic landscape descriptions stenciled on concrete curb stones poignant in their banality, and very sad.

Captions top to bottom:

"King Wave (Garden of Ascension)" (2005). 72” X 36”. Light-Jet Print on metal panel. "King Wave (Haven of Peace)" (2005). 72” X 36”. Light-Jet Print on metal panel.

"King Wave (Resurrection Slope)" (2005). 72” X 36”. Light-Jet Print on metal panel.

"King Wave (Garden of Ascension)" (2005). 72” X 36”. Light-Jet Print on metal panel. "King Wave (Haven of Peace)" (2005). 72” X 36”. Light-Jet Print on metal panel.

"King Wave (Resurrection Slope)" (2005). 72” X 36”. Light-Jet Print on metal panel.

SUZAN SHUTAN

My work focuses on the nimble and elastic relationship of two to three dimensional elements. Creating a constant negotiation between the flatness of industrial materials and the organic visceral transformations that happens in our three-dimensional world, my constructs extend in graceful gestures resonating ebb, flow, and intersection of lines and pathways. I combine the handmade and industrial into colorful patterned pieces that draw from ecological systems and life processes such as movement, reproduction, and growth, illustrating natural and human-made occurrences whose detritus allows for unexpected changes. Rooted in Process Art, at its core lays an organic geometry.

My "Tar Clusters" series was initially derived from algorithms used by computer scientists to detect oil slicks using SAR, the Synthetic Aperture Radar which remotely senses and maps the surface of Earth creating images from satellite missions. In 2012, there were 3,800 fixed platforms and 37,000 miles of pipeline documented in the Gulf of Mexico. There are many more now. The use of algorithms determined pathways of destruction to the marine ecosystem. I use and repurpose tar roofing paper, a forgiving and flexible material made from asphalt which comes from the distillation process of selected crude oils, because it is a common building substance that most of us live with but is harmful to the environment in its creation and disposal.

Made of hundred pieces of various sized paper looped and attached to each other, my installations organically grow and morph, referencing a variety of things from knitting to atoms, molecules, and populations. Metaphorically, the tar paper is suggestive of sustainability issues at the process level; and forms of clusters from this paper which I link together reference clustered data at a conceptual level. I use my artistic license to create sensually brooding work that speaks to both the destructive nature of our human carbon footprint and the restorative attempt to issue damage control across the planets oceans and in our groundwater reservoirs. The colored areas are indicative of erosion due to fertilizers, pesticides, detergents, and household chemicals. It is intentional to form the tar roofing paper into undulating patterns that capture moments of ephemeral beauty in the midst of toxic transformation.

My "Tar Clusters" series was initially derived from algorithms used by computer scientists to detect oil slicks using SAR, the Synthetic Aperture Radar which remotely senses and maps the surface of Earth creating images from satellite missions. In 2012, there were 3,800 fixed platforms and 37,000 miles of pipeline documented in the Gulf of Mexico. There are many more now. The use of algorithms determined pathways of destruction to the marine ecosystem. I use and repurpose tar roofing paper, a forgiving and flexible material made from asphalt which comes from the distillation process of selected crude oils, because it is a common building substance that most of us live with but is harmful to the environment in its creation and disposal.

Made of hundred pieces of various sized paper looped and attached to each other, my installations organically grow and morph, referencing a variety of things from knitting to atoms, molecules, and populations. Metaphorically, the tar paper is suggestive of sustainability issues at the process level; and forms of clusters from this paper which I link together reference clustered data at a conceptual level. I use my artistic license to create sensually brooding work that speaks to both the destructive nature of our human carbon footprint and the restorative attempt to issue damage control across the planets oceans and in our groundwater reservoirs. The colored areas are indicative of erosion due to fertilizers, pesticides, detergents, and household chemicals. It is intentional to form the tar roofing paper into undulating patterns that capture moments of ephemeral beauty in the midst of toxic transformation.