Shirley Steele

Interview by Kate Schwarting, Programs Manager

KS: How has your work as a research scientist in speech and linguistics impacted your art?

SS: My work as a research scientist, at AT&T Bell Laboratories, Texas Instruments, and Unisys Corporation, was about spoken language and how linguistic knowledge might be used in contemporary applications like computer speech synthesis and speech recognition. I am still fascinated with language, and I am interested in exploring linguistic concepts in my artwork. So I spent a long time trying to decide how to represent spoken language visually. Speech scientists use direct representations of speech (waveforms, spectrograms, fundamental frequency contours, etc.), but these are unintelligible to many people. Ultimately, I realized that there are already visual forms of language that are widely understood: that is, orthographic systems, or writing.

Orthographies are varied and interesting and not all of them are based on the alphabet that English speakers are familiar with. There are ancient writing systems, like cuniform and hieroglyphics; somewhat newer ones, like those based on the alphabet; and more recently, brand new systems generated by the widespread use of computers. In visual terms, I’m exploring the idea that language is not static. We are continuously reinventing it and its visual representations.

KS: In some of your series, such as "Hand and Machine," images are created with both computer code as well as traditional painting. How did you develop this process?

SS: When I used coding in my scientific career, I could see that it might eventually be an exciting tool for visual exploration. So years later, when graphics programming languages became widely available, I found that I could explore coding as a whole new medium. Also, with coding, I could escape the limits of commercially available graphics tools. One of the early artworks I did with coding was a short animated video which was shown on the Crown Lights on the top of the 27-story Philadelphia Electric Company building in Philadelphia in 2010.

Animations are enormously rewarding to create and in fact, I am still making them. However, eventually I felt the need to see evidence of the human hand in the artwork. After all, the machine does not create things by itself, at least not without a human to tell it how. So, I have developed a practice that allows the viewer to see human elements along with the result of a coded algorithm.

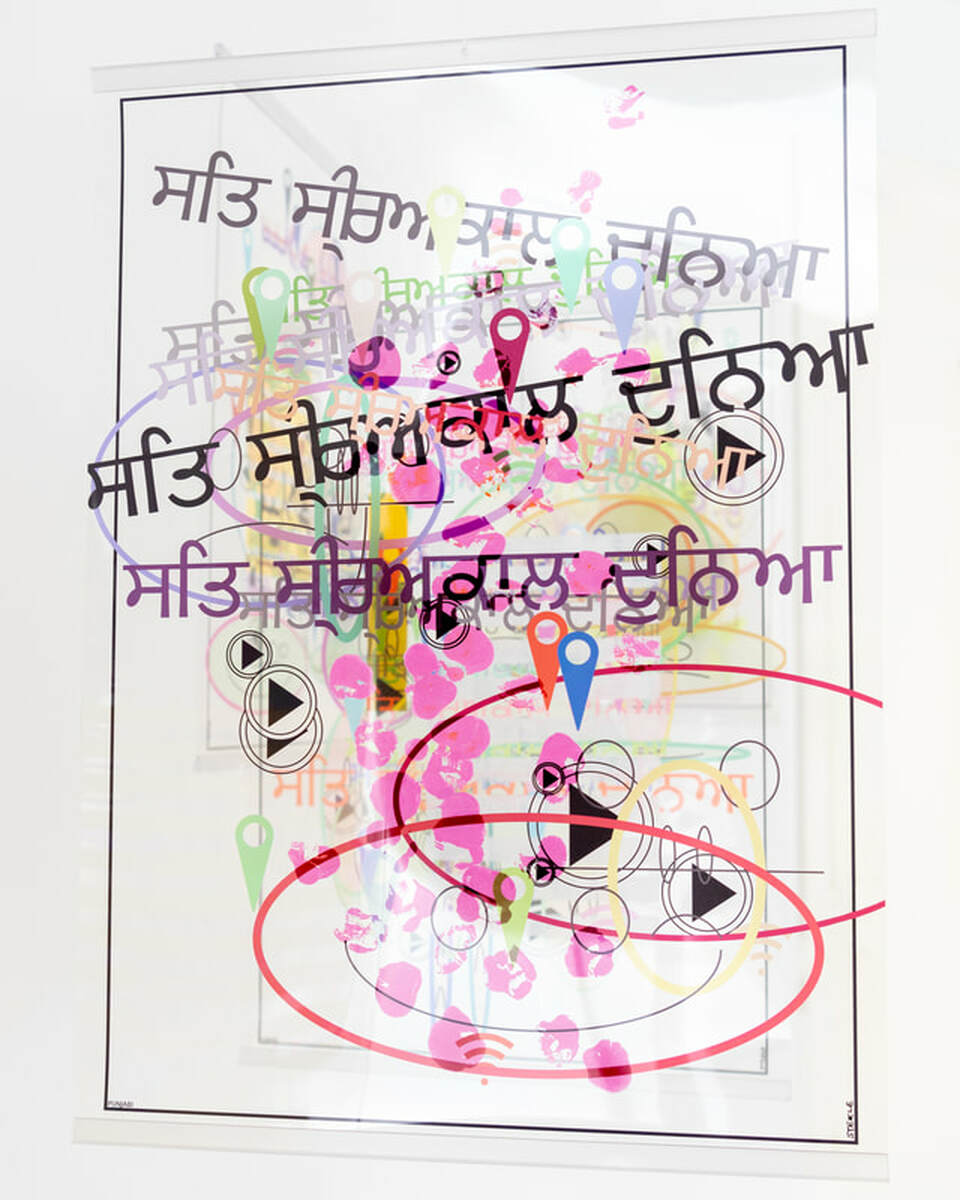

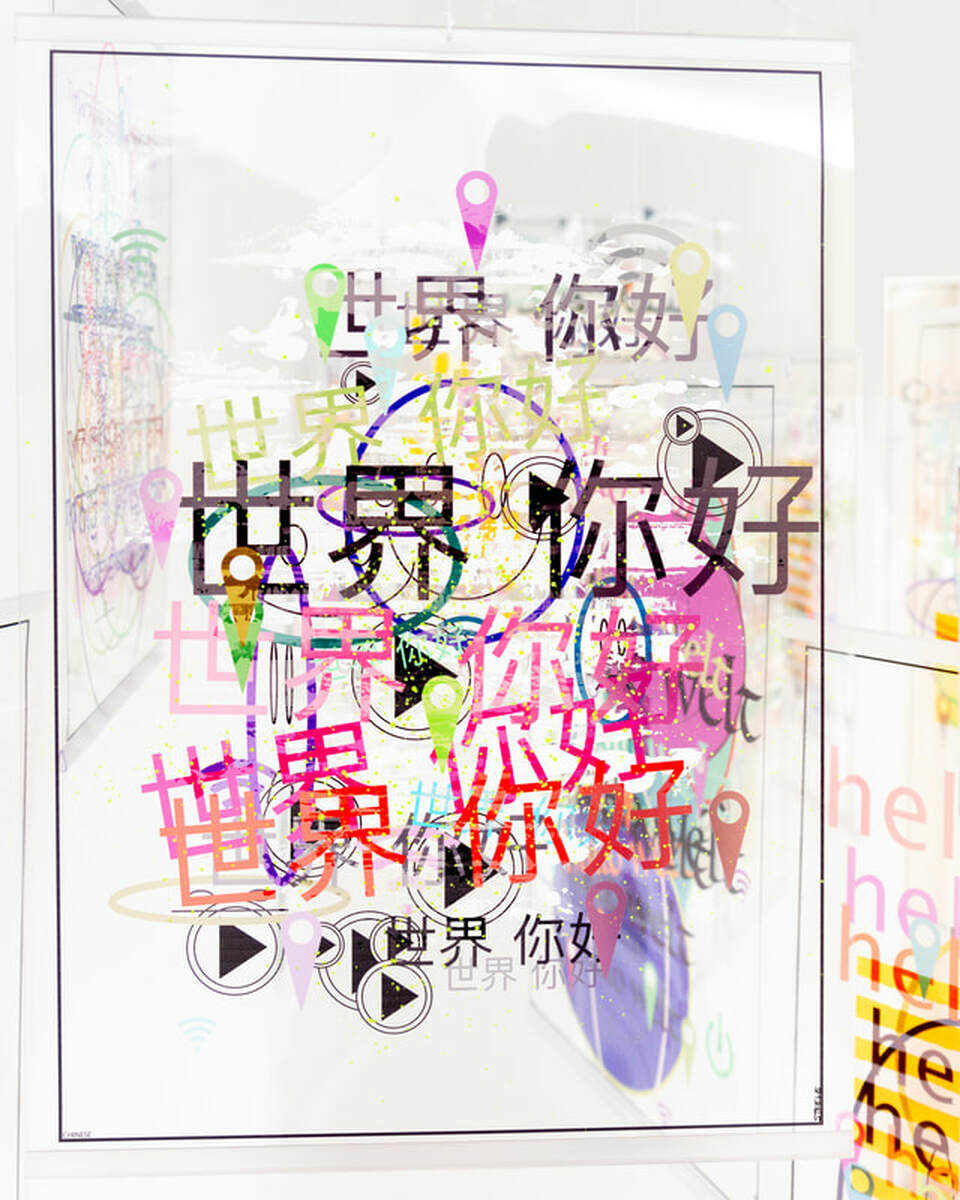

First, I write a computer animation. I include randomization in parts of the code, so that I almost know what the final result will look like, but not quite. My artwork reflects the fact that events are in some measure planned, but in many ways unpredictable. I run the program many times in order to get a visual sketch that I like, deleting all the rejects right away. When the program produces a satisfactory image, I save a stop-action frame, and that becomes the basis for a new piece. Next, I have the image printed on transparent acetate, and then I paint on one or both sides so that you can see the gesture of the hand. I use transparencies so that the viewer can see through one to the others, revealing multiple layers of hand and machine.

SS: When I used coding in my scientific career, I could see that it might eventually be an exciting tool for visual exploration. So years later, when graphics programming languages became widely available, I found that I could explore coding as a whole new medium. Also, with coding, I could escape the limits of commercially available graphics tools. One of the early artworks I did with coding was a short animated video which was shown on the Crown Lights on the top of the 27-story Philadelphia Electric Company building in Philadelphia in 2010.

Animations are enormously rewarding to create and in fact, I am still making them. However, eventually I felt the need to see evidence of the human hand in the artwork. After all, the machine does not create things by itself, at least not without a human to tell it how. So, I have developed a practice that allows the viewer to see human elements along with the result of a coded algorithm.

First, I write a computer animation. I include randomization in parts of the code, so that I almost know what the final result will look like, but not quite. My artwork reflects the fact that events are in some measure planned, but in many ways unpredictable. I run the program many times in order to get a visual sketch that I like, deleting all the rejects right away. When the program produces a satisfactory image, I save a stop-action frame, and that becomes the basis for a new piece. Next, I have the image printed on transparent acetate, and then I paint on one or both sides so that you can see the gesture of the hand. I use transparencies so that the viewer can see through one to the others, revealing multiple layers of hand and machine.

KS: What is your perspective on the impact of integrating art and science?

SS: Currently, there are many scientists who are using principles of art and design for understanding data (e.g., Edward Tufte’s information design and data visualization). Also, there are many artists currently working who are exploring scientific and mathematical topics as subject matter (e.g., Manfred Mohr’s paths through 11-dimensional hypercubes). Science and art are different ways of understanding the world, but they are not wholly incompatible. Both disciplines offer the opportunity for the discovery of something you have never seen before or which perhaps nobody has ever seen before.

In 1959, the British intellectual C.P. Snow described the existence of a major divide in western society in a lecture entitled The Two Cultures. His thesis was that the sciences and the humanities are separate cultures, and that people on each side of the divide are shamefully ignorant of the other. Perhaps the imaginative combining of science and art, by people who are interested in learning about a different discipline, can help to bridge C.P. Snow’s divide.

SS: Currently, there are many scientists who are using principles of art and design for understanding data (e.g., Edward Tufte’s information design and data visualization). Also, there are many artists currently working who are exploring scientific and mathematical topics as subject matter (e.g., Manfred Mohr’s paths through 11-dimensional hypercubes). Science and art are different ways of understanding the world, but they are not wholly incompatible. Both disciplines offer the opportunity for the discovery of something you have never seen before or which perhaps nobody has ever seen before.

In 1959, the British intellectual C.P. Snow described the existence of a major divide in western society in a lecture entitled The Two Cultures. His thesis was that the sciences and the humanities are separate cultures, and that people on each side of the divide are shamefully ignorant of the other. Perhaps the imaginative combining of science and art, by people who are interested in learning about a different discipline, can help to bridge C.P. Snow’s divide.

KS: Do you have any projects or exhibitions you are currently involved with?

SS: For the last year, I have been working on a series called hello world. The phrase “hello world” is a meme well known in the tech community. It originated as a screen test message in a Bell Laboratories tutorial memo for the then-new C programming language (Kernighan 1974). Novice programmers still often learn their first programming concepts by printing “hello world” to the screen.

My hello world series represents the meme in many different languages. In this way, I hope to highlight the ubiquity and universality of computing in human life. So far, I have created pieces in Chinese, English, French, German, Korean, Punjabi, Spanish, and Urdu. This somewhat idiosyncratic list reflects my acquaintance with individual native speakers who can verify my transcription of “hello world”. Part of the fun is researching different languages and finding native speakers. There are many languages still on my to-do list. Also represented in the artwork are contemporary communicative symbols (emojis, location balloons, video play buttons, power-up buttons, and so on), alongside the standard orthography of different languages. Using the juxtaposition of traditional graphemes and contemporary memes, I invite the viewer to imagine the creation of orthography as an ongoing, living human endeavor.

SS: For the last year, I have been working on a series called hello world. The phrase “hello world” is a meme well known in the tech community. It originated as a screen test message in a Bell Laboratories tutorial memo for the then-new C programming language (Kernighan 1974). Novice programmers still often learn their first programming concepts by printing “hello world” to the screen.

My hello world series represents the meme in many different languages. In this way, I hope to highlight the ubiquity and universality of computing in human life. So far, I have created pieces in Chinese, English, French, German, Korean, Punjabi, Spanish, and Urdu. This somewhat idiosyncratic list reflects my acquaintance with individual native speakers who can verify my transcription of “hello world”. Part of the fun is researching different languages and finding native speakers. There are many languages still on my to-do list. Also represented in the artwork are contemporary communicative symbols (emojis, location balloons, video play buttons, power-up buttons, and so on), alongside the standard orthography of different languages. Using the juxtaposition of traditional graphemes and contemporary memes, I invite the viewer to imagine the creation of orthography as an ongoing, living human endeavor.