ES: How do you find jewelry to be an effective and useful medium for visual communication?

SJ: There are many examples of contemporary art makers using jewelry to communicate a range of larger or smaller subjects that are important to them: from commenting on social or political issues, to addressing craft discourses or semantics of pure aesthetics.

In my practice, instead of having work carry an explicit message, I rather tend to focus on enabling the audience to have certain art experiences. The goal for these is to be engaging, visceral and arousing a sense of wonder. Regardless of whether the experience is short-term or long lasting, it has to be powerful enough to mentally extract the audience member out of his or her immediate environment, even for a brief moment.

I enjoy crafting different strategies as to how objects can enable such an experience without being too direct, or literal. One of the aspects is engagement of the body as a whole, making the wearer become a performer of sorts, a participant. But jewelry format also has a lot of cultural baggage that is specifically associated with wear-ability as an ornamental attribute, and which limits people's engagement with the objects to just the surface, the visual aesthetics. In order to bypass this barrier, I find that the communication has to become subliminal, relying on the unique experience each audience member will have with the pieces in very close proximity.

Jewelry is one of the few art formats that can communicate through tactile interaction in addition to the visual one. Some of the methods I am exploring through small-scale jewelry objects have to do with the experience of perception through touch. And observing what happens when the audience has a chance to physically interact with the pieces in their own personal space, whether it is worn on the body or held in a hand.

SJ: There are many examples of contemporary art makers using jewelry to communicate a range of larger or smaller subjects that are important to them: from commenting on social or political issues, to addressing craft discourses or semantics of pure aesthetics.

In my practice, instead of having work carry an explicit message, I rather tend to focus on enabling the audience to have certain art experiences. The goal for these is to be engaging, visceral and arousing a sense of wonder. Regardless of whether the experience is short-term or long lasting, it has to be powerful enough to mentally extract the audience member out of his or her immediate environment, even for a brief moment.

I enjoy crafting different strategies as to how objects can enable such an experience without being too direct, or literal. One of the aspects is engagement of the body as a whole, making the wearer become a performer of sorts, a participant. But jewelry format also has a lot of cultural baggage that is specifically associated with wear-ability as an ornamental attribute, and which limits people's engagement with the objects to just the surface, the visual aesthetics. In order to bypass this barrier, I find that the communication has to become subliminal, relying on the unique experience each audience member will have with the pieces in very close proximity.

Jewelry is one of the few art formats that can communicate through tactile interaction in addition to the visual one. Some of the methods I am exploring through small-scale jewelry objects have to do with the experience of perception through touch. And observing what happens when the audience has a chance to physically interact with the pieces in their own personal space, whether it is worn on the body or held in a hand.

ES: Scale is evidently an important element of your visual discourse, when one looks at your entire collection of work. How does working on a diverse spectrum of materials, from steel to eggshells, fit into this dialectic?

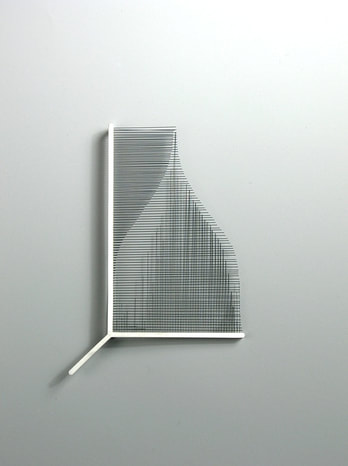

SJ: In the "Lineare" series, fabricated out of thinner than human hair, shape-memory Nitinol wire, pieces resemble fragments of drawings or engravings, but extruded into real 3-dimensional space. In this case, Nitinol is the only material in existence that allows me to build such intricate-looking structures, but retain overall function: wear-ability or simply the ability to be handled. The resulting optical illusions need to be seen in very close proximity to the observer to be effective, so the scale of those pieces is very intimate.

In a series titled "Accumulus," the aim was to bring a gigantic atmospheric phenomenon within actual grasp. The pieces are composed of materials we all recognize and handle regularly, like egg shell, glass frames, light bulbs and hair, but when transformed into a form referencing a cloud, they function as a paradoxical solidification of such an ethereal form. The scale here is once again in a very deliberate direct relationship with the body or hands.

Alternately, watch and clock hands are a very versatile material that I use in a variety of scales. The material has a fractal quality. In jewelry, or small scale sculptural pieces, amassing them into small structures creates a very intimate experience, while in larger projects, like the fences/barbed wire barriers, the materials function in a very expansive form. At each scale level, our understanding of the material is transformed when taken beyond the context of their original function.

SJ: In the "Lineare" series, fabricated out of thinner than human hair, shape-memory Nitinol wire, pieces resemble fragments of drawings or engravings, but extruded into real 3-dimensional space. In this case, Nitinol is the only material in existence that allows me to build such intricate-looking structures, but retain overall function: wear-ability or simply the ability to be handled. The resulting optical illusions need to be seen in very close proximity to the observer to be effective, so the scale of those pieces is very intimate.

In a series titled "Accumulus," the aim was to bring a gigantic atmospheric phenomenon within actual grasp. The pieces are composed of materials we all recognize and handle regularly, like egg shell, glass frames, light bulbs and hair, but when transformed into a form referencing a cloud, they function as a paradoxical solidification of such an ethereal form. The scale here is once again in a very deliberate direct relationship with the body or hands.

Alternately, watch and clock hands are a very versatile material that I use in a variety of scales. The material has a fractal quality. In jewelry, or small scale sculptural pieces, amassing them into small structures creates a very intimate experience, while in larger projects, like the fences/barbed wire barriers, the materials function in a very expansive form. At each scale level, our understanding of the material is transformed when taken beyond the context of their original function.

Cupola Graph Brooch, 2006, nitinol, syringe needles, silver. Courtesy of the artist.

Cupola Graph Brooch, 2006, nitinol, syringe needles, silver. Courtesy of the artist.

ES: What do you think is vital to moving the science/art dialogue forward?

SJ: I think there is a certain amount of isolationism that happens in each of these disciplines. I believe artists and scientists share a lot of same issues that prevents each, or general public as well, from really understanding or engaging with the other.

I often find that scientists like to give names, titles, classify and compartmentalize more than explain, engage and inspire. Sure, attributing precise terminology to explain often very complex phenomena is helpful for the initiated few, but rarely is inviting or easily approachable by others. Artists often fall into a similar trap of inventing a very complex, but self-absorbed visual language that often acts as a barrier for a pluralistic experience. I think both disciplines should look further to shed the rather elitist status that segregates each to their own protected fields of exploration.

So, it is the semantics of communication that I find a bit problematic. I think understanding this phenomenon would be very advantageous to help each other in areas we are not the strongest in. And that can be a part of the dialogue.

Sergey is based in High Falls, NY and teaches high-tech diamond setting in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

You can contact him at [email protected] and visit his website at www.jivetin.com.

SJ: I think there is a certain amount of isolationism that happens in each of these disciplines. I believe artists and scientists share a lot of same issues that prevents each, or general public as well, from really understanding or engaging with the other.

I often find that scientists like to give names, titles, classify and compartmentalize more than explain, engage and inspire. Sure, attributing precise terminology to explain often very complex phenomena is helpful for the initiated few, but rarely is inviting or easily approachable by others. Artists often fall into a similar trap of inventing a very complex, but self-absorbed visual language that often acts as a barrier for a pluralistic experience. I think both disciplines should look further to shed the rather elitist status that segregates each to their own protected fields of exploration.

So, it is the semantics of communication that I find a bit problematic. I think understanding this phenomenon would be very advantageous to help each other in areas we are not the strongest in. And that can be a part of the dialogue.

Sergey is based in High Falls, NY and teaches high-tech diamond setting in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

You can contact him at [email protected] and visit his website at www.jivetin.com.