Scott Chimileski

Interview by Alexandra Constantinou, Communications & Web Intern

Interview by Alexandra Constantinou, Communications & Web Intern

AC: How were you inspired to combine biology and photography? Did your great uncle, Rene´ Pauli, first introduce you to photography? What was your first piece of sciart?

SC: I’ve been both a biologist and an artist since before I knew what a scientist and an artist was. I was one of those kids who was happiest in the muck trudging through ponds near where I grew up in Connecticut, capturing whatever I could with nets and, for better or worse, bringing all of this life back home. At one point I had seven different aquariums in my room. Meanwhile, I was drawn to painting and other artistic media for as long as I can remember and in middle school I was moved to “gifted art” by one of my teachers. In 8th grade my homeroom teacher commissioned me to paint a mural of a neuron in a main hallway of my school. (Still there today!) That was my very first “official” piece of sciart. Mentioning this might seem silly 18 years later, however I think it’s important to realize how a few special teachers or a confidence boost like that can ripple forward throughout an entire lifetime.

SC: I’ve been both a biologist and an artist since before I knew what a scientist and an artist was. I was one of those kids who was happiest in the muck trudging through ponds near where I grew up in Connecticut, capturing whatever I could with nets and, for better or worse, bringing all of this life back home. At one point I had seven different aquariums in my room. Meanwhile, I was drawn to painting and other artistic media for as long as I can remember and in middle school I was moved to “gifted art” by one of my teachers. In 8th grade my homeroom teacher commissioned me to paint a mural of a neuron in a main hallway of my school. (Still there today!) That was my very first “official” piece of sciart. Mentioning this might seem silly 18 years later, however I think it’s important to realize how a few special teachers or a confidence boost like that can ripple forward throughout an entire lifetime.

The transition from painting to photography did start through the work of my great Uncle Rene´ Pauli. Rene´ was a photographer and print-maker who emigrated to the U.S. from Switzerland. He lived in a small apartment in San Francisco that doubled as a print shop. Every room was filled with complex machinery that he made by hand. He traveled across the National Parks of the U.S. to capture stunning photographs and worked to revive and perfect an old chemical print making process called tri-color carbon. The unique prints have exceptional resolution, 3D relief, and permanence, remaining unchanged for many hundreds of years. I remember visiting his apartment as a child and beyond the machines with exposed circuits, drive chains, buttons and flashing lights, I’ll never forget the little closet in the back where he even made his own paper from pulp.

Renée´ passed away in 1998 at the age of 63 when I was just 14 years old. Nevertheless, between the interactions I did have with him and his prints that filled the walls of my parent’s house, he was and still is a great source of inspiration. Around the same time that he passed away, my parents bought me my first entry-level SLR camera as a graduation gift (film of course!) That’s when my affinity towards nature began to combine with my artistic impulses and when I began to develop the craft of photography. All the while, my scientific track remained just as strong. It wasn’t until my work as PhD student while studying microbial communities called biofilms that my efforts as a photographer and as a biologist finally merged. And it was more than just taking pretty photos of microbes - I discovered a social motility phenomenon in the archaeal species Haloferax volcanii, akin to schooling fish, that I never could have seen without macroscopic time-lapse. Now, in my postdoctoral work with Roberto Kolter at Harvard Medical School, my continued research into microbial communities and collective behaviors has become completely inseparable from my imaging work.

AC: Your photography spans from microbiology to landscapes to astrophotography. For you, how do these different areas of science connect?

SC: This is an excellent observation and a great question which I am very excited to answer! But I would first like to turn the question upside down, if that is okay. Because for me, the question is not how these different size scales and subjects from astrophotography, to landscapes to microbiology connect, it is why do we as scientists and artists disconnect them in the first place? The human brain is great at separating different elements of nature and this has been essential during our evolution and success as a species. But that doesn’t mean that our separations are true to nature. As an artist and a writer, I draw from all matter of scientific disciplines and focus on the interconnectivity of nature: on the parallels and interdependence of phenomena occurring at different size scales, from microscopic, to everyday visible life, to the cosmos.

SC: This is an excellent observation and a great question which I am very excited to answer! But I would first like to turn the question upside down, if that is okay. Because for me, the question is not how these different size scales and subjects from astrophotography, to landscapes to microbiology connect, it is why do we as scientists and artists disconnect them in the first place? The human brain is great at separating different elements of nature and this has been essential during our evolution and success as a species. But that doesn’t mean that our separations are true to nature. As an artist and a writer, I draw from all matter of scientific disciplines and focus on the interconnectivity of nature: on the parallels and interdependence of phenomena occurring at different size scales, from microscopic, to everyday visible life, to the cosmos.

AC: You have partnered with the Harvard Museum of Natural History (HMNH) to spearhead an exhibition on Microbial Life and with Harvard University Press to write a book with Roberto Kolter, Life at the Edge of Sight, both due in fall 2017. How will this show and book showcase the microbial world to non-scientists? Why is this subject important to share with others?

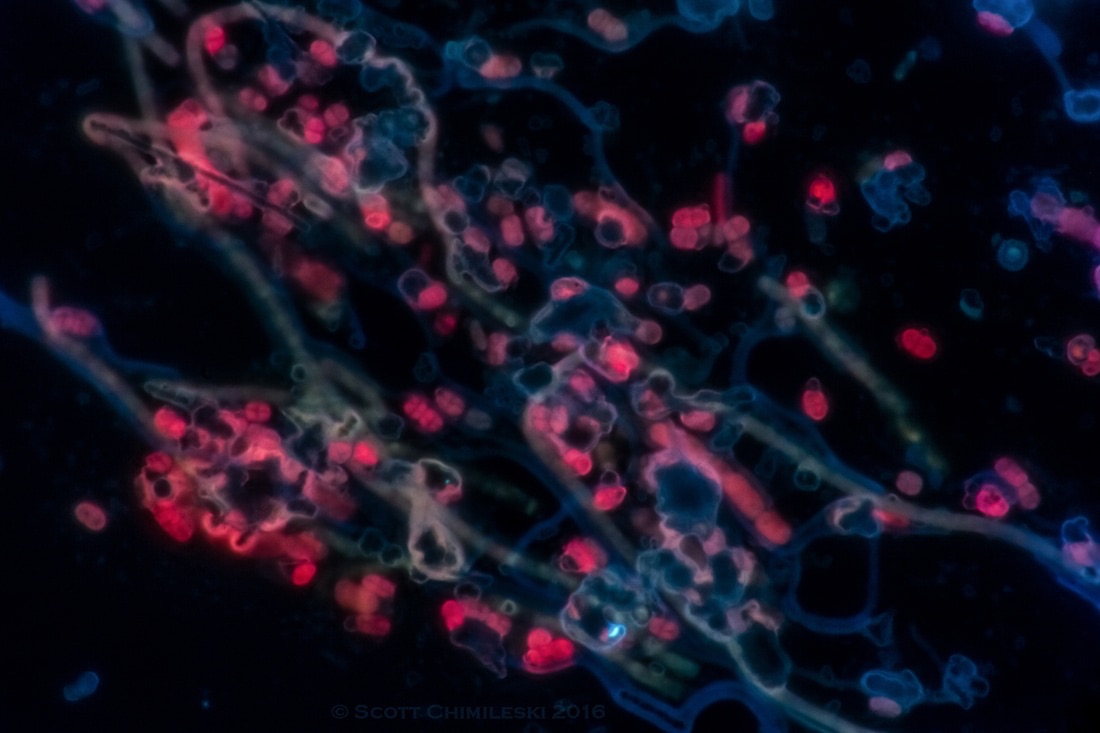

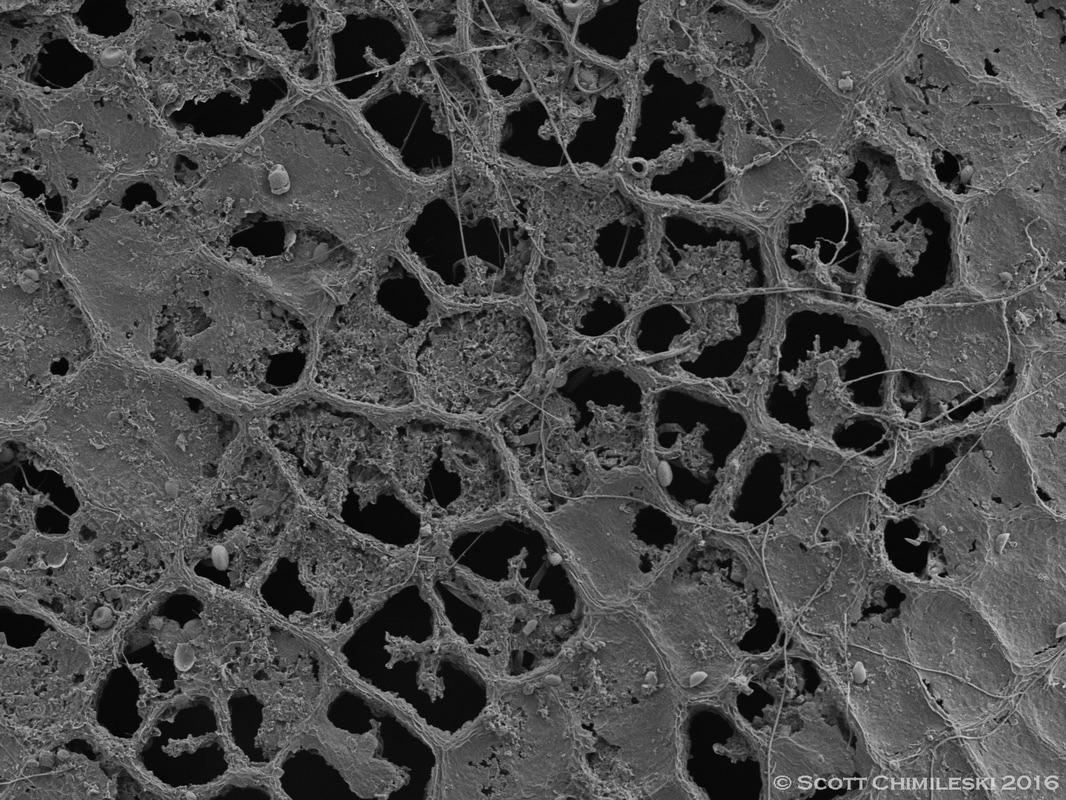

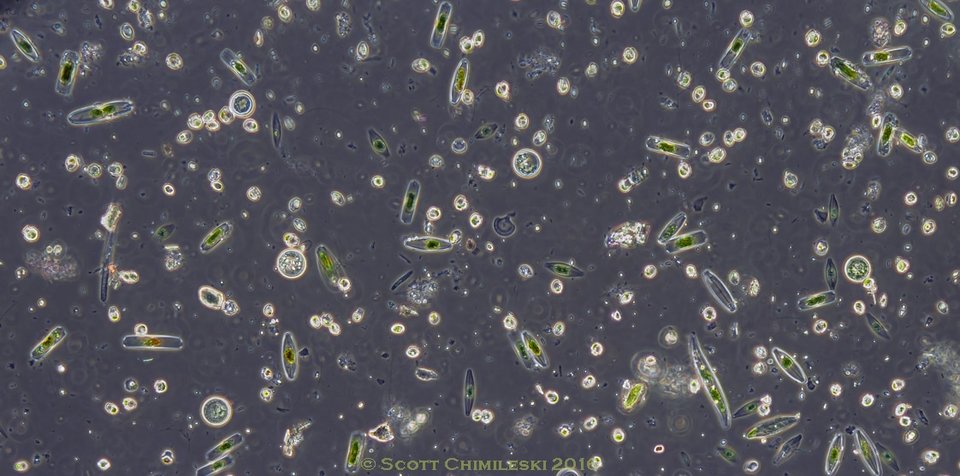

SC: The Microbial Life exhibition at the HMNH and the book Life at the Edge of Sight will both rely on images that I have captured across a range of size scales, from scanning electron microscopy, to light and fluorescence microscopy, to macro photography and on up to satellite imagery from NASA. At the HMNH, we’ll also make use of live microbes and live microbiologists to help look at them!

SC: The Microbial Life exhibition at the HMNH and the book Life at the Edge of Sight will both rely on images that I have captured across a range of size scales, from scanning electron microscopy, to light and fluorescence microscopy, to macro photography and on up to satellite imagery from NASA. At the HMNH, we’ll also make use of live microbes and live microbiologists to help look at them!

My mission is not just to bring a strong microbial presence to the HMNH - but to help spur a movement to bring microbial balance to all natural history museums. There’s a reason why this hasn’t already happened despite the fact that - no offense to the beautiful plants and animals - microbes make up the overwhelming majority of the natural history of Earth. As their name implies, most microbes are small. So, the intricate microscopic structures and interactions that underpin microbial activities are typically not out on display before our eyes. For example, a biofilm is a microbial ecosystem that functions like a rainforest. Although unlike a rainforest, we can’t go out and walk inside of a biofilm to see the monkeys swinging from tree to tree, so to speak. I am developing all of these imaging methods, time-lapse techniques and 3D modeling to take that invisible world and present it to the public in a tangible form so that everyone can appreciate microbes.

Why is it important to appreciate and share these microbial worlds? What a great question! Where do I start? I could answer the question of why microbial science is important to share in dozens of different ways, and indeed these will be highlighted in the Microbial Life exhibition and in the book. We are talking about microbes as the organisms that produce the oxygen we bring into our lungs each second, microbes as the ancestor of the endosymbiotic mitochondria that power every one of our human cells, microbes as the foundation of the global ecosystem, and, just one more reason for now, microbes as the makers of our medicines and of some of our most delicious foods and drinks from cheese, to wine, beer, chocolate and coffee! Yes, there is an infinitesimally small minority of microbes that cause disease and these species will continue to cause harm to humanity. But when we readjust our perspective in this way, we realize there is much more to love than to fear in the microbial world.

You can find Scott online:

Website: microbephotography.com

Twitter: @socialmicrobes

Instagram: @scott_chimileski

Website: microbephotography.com

Twitter: @socialmicrobes

Instagram: @scott_chimileski