ES: What led you to the invasive species research you are currently working on?

RP: My initial interest in birds began during a summer exploring the woods of my home state, Rhode Island. My friends and I thought we could become more like the owls we occasionally saw swooping through the forest if we shifted to a nocturnal sleeping schedule. We had such fun, and I was enthralled with the host of new species we saw around our cabins when most people were comfortably sleeping. Fast forward a couple of decades, and I remain in awe of the natural world, particularly focusing on the ecology of invasive species: What makes certain species successful when brought to new places, and how do they spread? My interest in invasive species really grew from many conversations with my PhD advisors, and by becoming familiar with the long human history of moving species (intentionally or unintentionally) from one place to another.

Currently, as a doctoral student in Hunter College’s Animal Behavior and Comparative Psychology training area, I’m interested in the behavioral ecology of an introduced species, the Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis). The Myna was first observed near Miami in 1983, and the population has persisted and spread (albeit slowly) up the Florida panhandle. The bird is native to India and Southeast Asia, but is established in Australia, South Africa, Israel and many other locations. I recently returned from a field season in Homestead, FL where I began running preliminary behavioral experiments to assess traits that make this species a successful invader.

RP: My initial interest in birds began during a summer exploring the woods of my home state, Rhode Island. My friends and I thought we could become more like the owls we occasionally saw swooping through the forest if we shifted to a nocturnal sleeping schedule. We had such fun, and I was enthralled with the host of new species we saw around our cabins when most people were comfortably sleeping. Fast forward a couple of decades, and I remain in awe of the natural world, particularly focusing on the ecology of invasive species: What makes certain species successful when brought to new places, and how do they spread? My interest in invasive species really grew from many conversations with my PhD advisors, and by becoming familiar with the long human history of moving species (intentionally or unintentionally) from one place to another.

Currently, as a doctoral student in Hunter College’s Animal Behavior and Comparative Psychology training area, I’m interested in the behavioral ecology of an introduced species, the Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis). The Myna was first observed near Miami in 1983, and the population has persisted and spread (albeit slowly) up the Florida panhandle. The bird is native to India and Southeast Asia, but is established in Australia, South Africa, Israel and many other locations. I recently returned from a field season in Homestead, FL where I began running preliminary behavioral experiments to assess traits that make this species a successful invader.

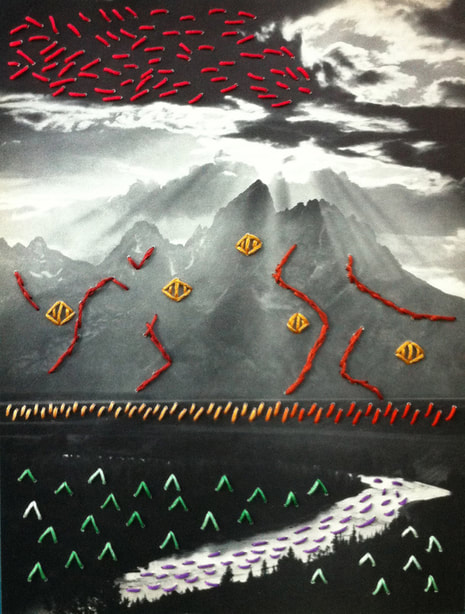

Starlings in Central Park 10" x 8.75", embroidery on fabric, 2015. Image courtesy of the Artist.

Starlings in Central Park 10" x 8.75", embroidery on fabric, 2015. Image courtesy of the Artist.

ES: I love that you do embroidery and that your artwork seems to reflect some of the ideas you bring to the field while doing research. Can you describe a bit your approach to your art-making?

RP: Thanks so much! It’s absolutely true that my research is reflected in my artwork and vice versa. Most ideas for my embroidery pieces begin after reading a journal article on a particular species, or after returning from field work and feeling the need to sort through new ideas and theories while engaging in some creative work—embroidery has been the perfect medium for this!

One of my more recent embroidery pieces illustrates this back and forth between science and art in my own practice. There is the infamous story of the European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) that was introduced to North America. In the late 19th century, a Shakespeare fanatic set about releasing every bird mentioned in Shakespeare’s writing to North America. The most successful of the lot was the Starling, which after releases of 60 individuals in 1890 and another 40 in 1891 (both in Central Park), now number over 200 million and range from Canada to Mexico and all the way across the U.S. to the Pacific. In my European Starling embroidery, I attempted to capture the image of a species that is more widespread than its initial releaser could have imagined. The portrait of a tiny starling, ringed in a gold chain stitch on a swirling blue/green background, belies its true impact, when we know a bit more about the life history of this very relentless introduced species.

My other embroideries fall along similar lines. The Irish Elk went extinct approximately 7,000 years ago, with major causes of their population decline still being debated. The Elk was enormous, and sported antlers that could be up to 12 feet wide. In my Irish Elk embroidery, I decided to again contrast the Elk skeleton with a more pastoral floral landscape. I found the perfect piece of thrift store fabric for the Elk, and began work on the stark skeleton. After that was finished, I added vibrant colorful flowers to symbolize lasting memories of a long gone species.

RP: Thanks so much! It’s absolutely true that my research is reflected in my artwork and vice versa. Most ideas for my embroidery pieces begin after reading a journal article on a particular species, or after returning from field work and feeling the need to sort through new ideas and theories while engaging in some creative work—embroidery has been the perfect medium for this!

One of my more recent embroidery pieces illustrates this back and forth between science and art in my own practice. There is the infamous story of the European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) that was introduced to North America. In the late 19th century, a Shakespeare fanatic set about releasing every bird mentioned in Shakespeare’s writing to North America. The most successful of the lot was the Starling, which after releases of 60 individuals in 1890 and another 40 in 1891 (both in Central Park), now number over 200 million and range from Canada to Mexico and all the way across the U.S. to the Pacific. In my European Starling embroidery, I attempted to capture the image of a species that is more widespread than its initial releaser could have imagined. The portrait of a tiny starling, ringed in a gold chain stitch on a swirling blue/green background, belies its true impact, when we know a bit more about the life history of this very relentless introduced species.

My other embroideries fall along similar lines. The Irish Elk went extinct approximately 7,000 years ago, with major causes of their population decline still being debated. The Elk was enormous, and sported antlers that could be up to 12 feet wide. In my Irish Elk embroidery, I decided to again contrast the Elk skeleton with a more pastoral floral landscape. I found the perfect piece of thrift store fabric for the Elk, and began work on the stark skeleton. After that was finished, I added vibrant colorful flowers to symbolize lasting memories of a long gone species.

|

ES: How do you find the development of a SciArt discourse to be helpful?

RP: For me, a SciArt discourse is helpful for a number of reasons. Most recently, while at my field site near the Everglades, I was invited to show some of my embroideries at a gallery in Miami called SwampSpace. As part of the month-long show I gave a talk about invasive species in south Florida. To me, this was an amazing opportunity that only came about because of a healthy SciArt discourse. I answered questions about the birds or snails residents see everyday in their communities and I asked attendees about their perceptions of invasive species as people who live so close to such biodiverse areas as Everglades and Biscayne National Parks. Back in Providence, RI before I began graduate school, I worked with a wonderful arts mentoring program for high school students called New Urban Arts. I found that oftentimes art was a wonderful place to begin talking about science. In one particularly Science and Art blended week, I talked to students at a local high school’s environmental club about migratory birds they might see in the area. Later that week, the students came over to the art studio, and we built nest boxes that were installed at their high school. Back in NYC, I truly look forward to all SciArt Center gatherings as a way to continue this dialogue when I’m not in the field. I inevitably leave each of our meetings with a wealth of novel ways to approach my creative projects and scientific practices. Rob is a Doctoral Student in the Animal Behavior and Comparative Psychology program at Hunter College, CUNY. Learn more about his research and artwork at www.robpecchia.com. To contact Rob you can email him at [email protected]. |