Matej Vakula

Interview by Alexandra Constantinou, Communications & Web Intern

AC: Your work has dealt with many different areas of science, from neuroscience to astrophysics to artificial intelligence. How do you choose which area of science to explore next? Which area are you currently working in?

MV: Currently, I am working in biology, specifically with nanoparticle-based drug discovery and computational chemistry. All of these different disciplines are closely related because of their shared focus on cancer treatment. Particularly in the Heller Lab at the Memorial Sloan Kettering with whom I am collaborating already almost for two years. Interdisciplinarity, in science, is becoming a key factor for advancement not only cancer research but any other area of biology or medicine. A major part of computational chemistry is based on machine learning and other forms of AI, automating discovery of new drugs and chemical compounds. AI, on the other hand, has close to neuroscience.

AC: You brought together eight artists, scientists, sociologists and futurologists in your Spaceship Jasny Dom project for a Futurological Congress to talk about the future of art. Why was it important to you to include non-artists in this discussion?

MV: The non-artists were crucial in the discussion. First the scientists together with the futurologists very loosely described a direction, the scientific discovery, and technology might be heading in the next fifty years. Based on that, and other sociopolitical circumstances, the sociologist described a possible state of the society. Finally, followed by art theorists, and artists, who tried to extrapolate possible forms of art within that future society. It was very exciting to observe what results would such collaboration across such vast spectrum of disciplines produce and most importantly, how would such transdisciplinary communication work. Without the non-artists, the artists would have nothing to build on.

MV: The non-artists were crucial in the discussion. First the scientists together with the futurologists very loosely described a direction, the scientific discovery, and technology might be heading in the next fifty years. Based on that, and other sociopolitical circumstances, the sociologist described a possible state of the society. Finally, followed by art theorists, and artists, who tried to extrapolate possible forms of art within that future society. It was very exciting to observe what results would such collaboration across such vast spectrum of disciplines produce and most importantly, how would such transdisciplinary communication work. Without the non-artists, the artists would have nothing to build on.

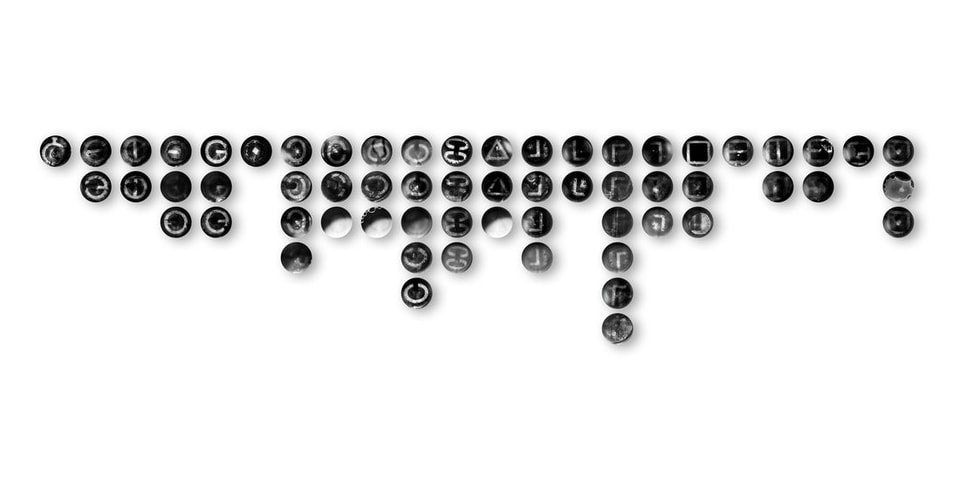

AC: One of your recent projects, Well Plate Utopias, combines Thomas Moore's utopian alphabet with experimental cancer drugs. You wrote that we should think about "the concept of Utopia as a fruitful path, rather than a destination" and "the laboratory as a place where the future is produced." How did this project come about?

MV: When I joined the Daniel Heller Lab, they were testing new nanoparticle-based cancer drugs for photothermal therapy. I recreated the testing process for these experimental nanoparticle-based drugs by growing a monolayer of tissue in a petri dish, adding the drug, and shining an infrared laser onto the dish. The laser activated the drug, which reminded me of analog photo processing; therefore, I started projecting images of letters onto the cancer tissue in this way. This project evolved into a discovery of an entirely new artistic technique but also inspired a discovery of a new form of experimental cancer surgery. Testing of the surgery is ongoing through 2017. Since the image is invisible to the eye, it needs to be photographed using an infrared camera and digitalized. Afterward, it is printed on specialized circular aluminum sheets using dye-sub print technology. Together they are composing a grid of 60 images, 22 different letters in total with 7.8 inches in diameter per letter. Each well plate depicts a letter from Sir Thomas More’s 16th-century imaginary alphabet, the basis for the spoken language on the island of Utopia.

MV: When I joined the Daniel Heller Lab, they were testing new nanoparticle-based cancer drugs for photothermal therapy. I recreated the testing process for these experimental nanoparticle-based drugs by growing a monolayer of tissue in a petri dish, adding the drug, and shining an infrared laser onto the dish. The laser activated the drug, which reminded me of analog photo processing; therefore, I started projecting images of letters onto the cancer tissue in this way. This project evolved into a discovery of an entirely new artistic technique but also inspired a discovery of a new form of experimental cancer surgery. Testing of the surgery is ongoing through 2017. Since the image is invisible to the eye, it needs to be photographed using an infrared camera and digitalized. Afterward, it is printed on specialized circular aluminum sheets using dye-sub print technology. Together they are composing a grid of 60 images, 22 different letters in total with 7.8 inches in diameter per letter. Each well plate depicts a letter from Sir Thomas More’s 16th-century imaginary alphabet, the basis for the spoken language on the island of Utopia.

Find Matej online:

Websites: vakula.eu and clakula.org

Twitter: @MatejVakula

Instagram: @matej_vakula

Facebook: Matej Vakula

Websites: vakula.eu and clakula.org

Twitter: @MatejVakula

Instagram: @matej_vakula

Facebook: Matej Vakula