ES: The relationship of biology to technology is interesting--some say it is wrought with contradictions, others say that it provides significant parallels that we can find useful. How did "bio-curiosity" enter your work with design and digital art?

KI: I’ve always been interested in nature--the patterns and textures found in plant life, anatomy, birds (both aesthetically and behaviorally), natural life cycles, emergence and naturalism. In terms of subject matter, the world of microbiology was a natural progression for me, so conceptually, it was an easy jump from the natural world into biotechnology. Practically speaking, however, understanding the tools and concepts behind biotechnology has required a whole lot more effort than I’d ever have imagined.

I met Daniel Grushkin and Wythe Marschall because they spoke at my event series, The Empiricist League (more on that below). Dan is one of the founding members of Genspace a community biotech lab in Brooklyn. I became interested in Genspace and decided to take Ellen Jorgensen’s biotech crash course. Ellen’s class was a pivotal moment for me.

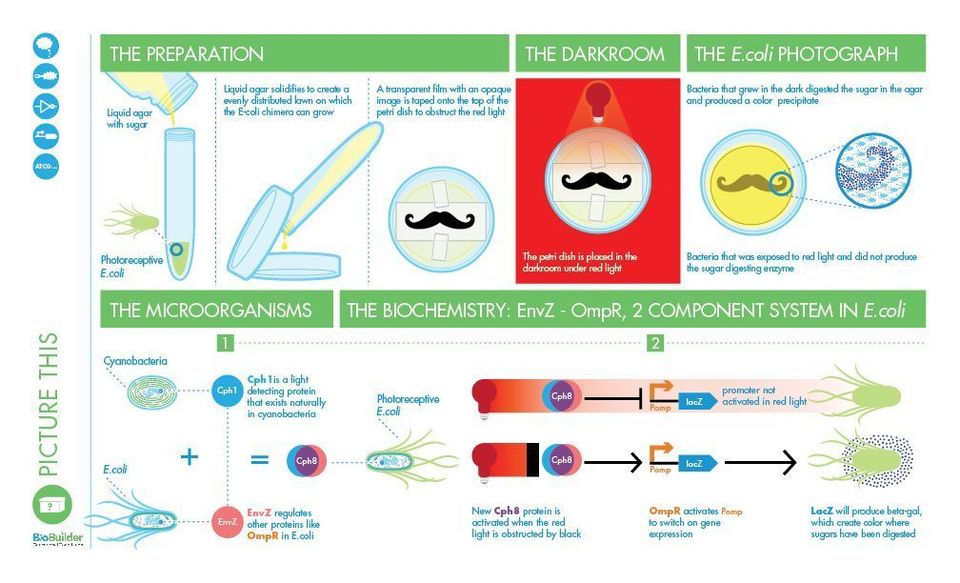

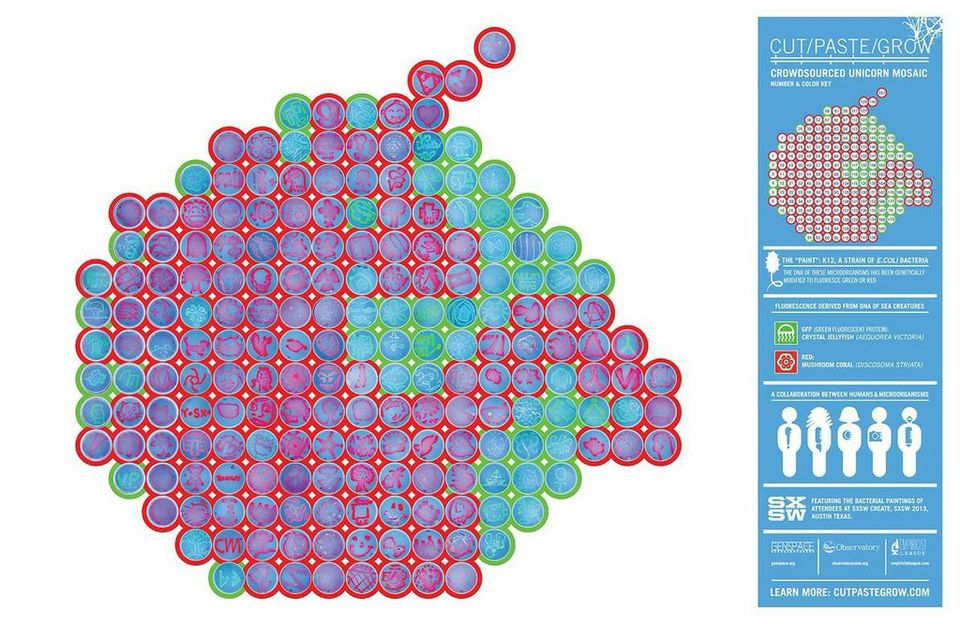

Dan and Wythe also asked me to help them with a bioart exhibit they were curating called "Cut/Paste/Grow." As part of what we were collecting for the exhibit, Wythe and I went one morning to MIT to observe Natalie Kuldell's bacterial photography lab in her synthetic biology class. Natalie is the founder of the Biobuilder Foundation, an organization dedicated to making “teachable modules” for synthetic biology. We engineered bacteria that responds to light; we placed a film over the bacteria in a Petri dish, and the bacteria was supposed to react to the dark areas and form an image. Unfortunately, our plates failed to produce an image. I was not to be daunted, and set out to try to create some sort of graphical representation that would distill what I had tried to do in the lab. Going through the motions of the protocol had been interesting, but I was oddly inspired by the fact that our lab had failed, and I wanted a 'picture' of what was supposed to have happened on a microbial level.

KI: I’ve always been interested in nature--the patterns and textures found in plant life, anatomy, birds (both aesthetically and behaviorally), natural life cycles, emergence and naturalism. In terms of subject matter, the world of microbiology was a natural progression for me, so conceptually, it was an easy jump from the natural world into biotechnology. Practically speaking, however, understanding the tools and concepts behind biotechnology has required a whole lot more effort than I’d ever have imagined.

I met Daniel Grushkin and Wythe Marschall because they spoke at my event series, The Empiricist League (more on that below). Dan is one of the founding members of Genspace a community biotech lab in Brooklyn. I became interested in Genspace and decided to take Ellen Jorgensen’s biotech crash course. Ellen’s class was a pivotal moment for me.

Dan and Wythe also asked me to help them with a bioart exhibit they were curating called "Cut/Paste/Grow." As part of what we were collecting for the exhibit, Wythe and I went one morning to MIT to observe Natalie Kuldell's bacterial photography lab in her synthetic biology class. Natalie is the founder of the Biobuilder Foundation, an organization dedicated to making “teachable modules” for synthetic biology. We engineered bacteria that responds to light; we placed a film over the bacteria in a Petri dish, and the bacteria was supposed to react to the dark areas and form an image. Unfortunately, our plates failed to produce an image. I was not to be daunted, and set out to try to create some sort of graphical representation that would distill what I had tried to do in the lab. Going through the motions of the protocol had been interesting, but I was oddly inspired by the fact that our lab had failed, and I wanted a 'picture' of what was supposed to have happened on a microbial level.

GFP pattern, 2013. An ode to GFP, featuring E.coli, the Crystal Jellyfish, and the

unicorn. Courtesy of the artist.

GFP pattern, 2013. An ode to GFP, featuring E.coli, the Crystal Jellyfish, and the

unicorn. Courtesy of the artist.

I spent a few months on my couch, referencing various scientific papers, articles in Nature, a smattering of notes I had taken, and some photos of sketches Natalie had made on the chalkboard. At the time, I couldn’t find a visual language for synthetic biology, so I had to improvise (since then, SBOL--Synthetic Biology Open Language - has evolved as a standard). I’m not a scientist, and fumbling through these scientific works, I grew to have a deep reverence and appreciation for the knowledge scientists acquire through schooling. There’s a good reason people in biotech fields go to school for so long. It was quite a cryptic endeavor.

Eventually I made something that I felt good enough about to share with someone who was familiar with the science. Oliver Medvedik at Genspace was kind enough to give me :30 of feedback, after asking me, “Why are you doing this?” My answer was to see if I could make sense of it. In effect, I wanted to explain it to myself, and others like me. With Oliver’s feedback, I polished up what I had done it was ready to share my work. Little did I know, that Natalie was going to publish a book, which would be a collection of labs she had compiled that were inspired by iGEM (a genetic engineering competition) projects. This began a wonderful collaboration. The book is slated to come out this spring. Natalie, Katie Hart, Rachael Bernstein, and myself have worked tirelessly on Biobuilder over the past few months, and I am looking forward seeing my diagrams and illustrations on the shelves of bookstores, labs, educational institutions, and hack spaces.

I’ve come to realize through working on Biobuilder, and tinkering in synbio, that electronics and code can be used to model biological processes. That’s the beauty of synthetic biology. It frames biology as a technology—an engineering process, but with DNA and RNA as the building blocks. The actions of enzymes and proteins can be viewed as the outputs, by detecting environmental toxins, treating disease, or by generating valuable medicines. It’s fascinating!

ES: Your recent projects surround the topic of biohacking. Can you explain a bit about what biohacking is and how it brings specialists into collaboration?

KI: One can look at biohacking from several different perspectives. Biohacking can be defined as engaging and tinkering with biology outside of traditional labs. The term 'hack' has begun to be synonymous with tinkering. It isn’t about people cooking up pathogens in garages and basements; that’s bioterrorism. Biohacking is: community labs like Genspace, or open workshops at museums, also, distributed science projects like those organized by Josiah Zayner, The ODIN and Synbiota. For me, biohacking has also been a way to learn more about biotechnology, and biology in general.

I’ve hacked with neuroscientists, microbiologists, other designers and artists, strategists, software developers, engineers… the list goes on. The hands-on experience of working with people of different disciplines results in collaborations that can foster a lot of ideas. It also creates a sense of mutual appreciation for both artisans and scientists.

Another experience that I had in biohacking and collaborating with a diverse group of specialists was when I participated in iGEM this past fall. iGEM is a genetic engineering competition that has traditionally only been open to biotech students, but through Genspace, I was able to participate in the newly minted Community Labs track. Our team was composed of an architect, a developer, an entrepreneur, some UX designers, an engineer, a filmmaker, as well as some scientists and microbiology students.

Recently I was accepted as a 2015 LEAP (Synthetic Biology Leadership Excellence Accelerator Program) fellow. I joined the ranks of some amazing technologists, scientists, policymakers, and innovators. I think it’s a sign that art- and design-centric biohackers like myself can help shape emerging technologies like synthetic biology. From using biotech materials as an artist medium, to pondering the role of biotech in the cultural through topics like policy-making and environmental effects, an artists’ view aides in the applications of technology, as it did when the internet was emerging as a platform. This energy is familiar to me- it reminds me of the sort of creative energy that was cropping in around the internet in the late 90s.

Eventually I made something that I felt good enough about to share with someone who was familiar with the science. Oliver Medvedik at Genspace was kind enough to give me :30 of feedback, after asking me, “Why are you doing this?” My answer was to see if I could make sense of it. In effect, I wanted to explain it to myself, and others like me. With Oliver’s feedback, I polished up what I had done it was ready to share my work. Little did I know, that Natalie was going to publish a book, which would be a collection of labs she had compiled that were inspired by iGEM (a genetic engineering competition) projects. This began a wonderful collaboration. The book is slated to come out this spring. Natalie, Katie Hart, Rachael Bernstein, and myself have worked tirelessly on Biobuilder over the past few months, and I am looking forward seeing my diagrams and illustrations on the shelves of bookstores, labs, educational institutions, and hack spaces.

I’ve come to realize through working on Biobuilder, and tinkering in synbio, that electronics and code can be used to model biological processes. That’s the beauty of synthetic biology. It frames biology as a technology—an engineering process, but with DNA and RNA as the building blocks. The actions of enzymes and proteins can be viewed as the outputs, by detecting environmental toxins, treating disease, or by generating valuable medicines. It’s fascinating!

ES: Your recent projects surround the topic of biohacking. Can you explain a bit about what biohacking is and how it brings specialists into collaboration?

KI: One can look at biohacking from several different perspectives. Biohacking can be defined as engaging and tinkering with biology outside of traditional labs. The term 'hack' has begun to be synonymous with tinkering. It isn’t about people cooking up pathogens in garages and basements; that’s bioterrorism. Biohacking is: community labs like Genspace, or open workshops at museums, also, distributed science projects like those organized by Josiah Zayner, The ODIN and Synbiota. For me, biohacking has also been a way to learn more about biotechnology, and biology in general.

I’ve hacked with neuroscientists, microbiologists, other designers and artists, strategists, software developers, engineers… the list goes on. The hands-on experience of working with people of different disciplines results in collaborations that can foster a lot of ideas. It also creates a sense of mutual appreciation for both artisans and scientists.

Another experience that I had in biohacking and collaborating with a diverse group of specialists was when I participated in iGEM this past fall. iGEM is a genetic engineering competition that has traditionally only been open to biotech students, but through Genspace, I was able to participate in the newly minted Community Labs track. Our team was composed of an architect, a developer, an entrepreneur, some UX designers, an engineer, a filmmaker, as well as some scientists and microbiology students.

Recently I was accepted as a 2015 LEAP (Synthetic Biology Leadership Excellence Accelerator Program) fellow. I joined the ranks of some amazing technologists, scientists, policymakers, and innovators. I think it’s a sign that art- and design-centric biohackers like myself can help shape emerging technologies like synthetic biology. From using biotech materials as an artist medium, to pondering the role of biotech in the cultural through topics like policy-making and environmental effects, an artists’ view aides in the applications of technology, as it did when the internet was emerging as a platform. This energy is familiar to me- it reminds me of the sort of creative energy that was cropping in around the internet in the late 90s.

“tsavo lion” “throttling grip”, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

“tsavo lion” “throttling grip”, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

ES: Community and curatorial work are a very visible part of your web presence as an artist. How do you see emphasizing these realms of art production as important to the breaching of disciplinary walls?

KI: I really enjoy community and curatorial work. I see it as creating conduits for engagement, curiosity, and collaboration. One forum in which I do that is through the Empiricist League. The Empiricist League is a science themed event series that’s held in bars. I co-curate it with David Leibowitz. The idea is to view popular subjects (like Love, Creativity, or the Apocalypse) through a scientific lens in an environment of a music venue; science-as-indie rock. People seem to enjoy these events--both the presenters and the community that attends. Our goals are to one, make science entertaining. Two, to pique curiosity around current scientific research. And three, bring together people from diverse scientific and creative backgrounds to explore new perspectives.

The Empiricist League has been hosting events in NY for almost three years. We just launched an Empiricist League chapter in San Francisco with David Litwak. We’re hoping to launch more chapters in other areas soon.

Meanwhile, Cut/Paste/Grow has turned into an ongoing collaboration. We’ve presented and exhibited at Maker Faire, the World Science Festival, and MOMA, and are continuing to evolve.

I’ve always been interested in community work. When I first started tinkering in code and digital art, I participated in several online design communities, including K10K (San Francisco) and Design Is Kinky (Sydney, Australia). Through my digital art motion experiments, I became involved in SXSW Interactive as a board member. The Interactive festival had its genesis in code and design, and has since evolved to much more. Code and design are still there, but now it’s clear that technology stretches across many fields and areas of life.

In general, I believe that both art and creative curation are important conduits for engaging people about science and technology. They give people a sense for the potential of a new technology, but also reveal its fragilities.

Karen lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

You can contact her at [email protected] and visit her awesome website at www.kareningram.com.

KI: I really enjoy community and curatorial work. I see it as creating conduits for engagement, curiosity, and collaboration. One forum in which I do that is through the Empiricist League. The Empiricist League is a science themed event series that’s held in bars. I co-curate it with David Leibowitz. The idea is to view popular subjects (like Love, Creativity, or the Apocalypse) through a scientific lens in an environment of a music venue; science-as-indie rock. People seem to enjoy these events--both the presenters and the community that attends. Our goals are to one, make science entertaining. Two, to pique curiosity around current scientific research. And three, bring together people from diverse scientific and creative backgrounds to explore new perspectives.

The Empiricist League has been hosting events in NY for almost three years. We just launched an Empiricist League chapter in San Francisco with David Litwak. We’re hoping to launch more chapters in other areas soon.

Meanwhile, Cut/Paste/Grow has turned into an ongoing collaboration. We’ve presented and exhibited at Maker Faire, the World Science Festival, and MOMA, and are continuing to evolve.

I’ve always been interested in community work. When I first started tinkering in code and digital art, I participated in several online design communities, including K10K (San Francisco) and Design Is Kinky (Sydney, Australia). Through my digital art motion experiments, I became involved in SXSW Interactive as a board member. The Interactive festival had its genesis in code and design, and has since evolved to much more. Code and design are still there, but now it’s clear that technology stretches across many fields and areas of life.

In general, I believe that both art and creative curation are important conduits for engaging people about science and technology. They give people a sense for the potential of a new technology, but also reveal its fragilities.

Karen lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

You can contact her at [email protected] and visit her awesome website at www.kareningram.com.