How do forests respond to the loss of their most important "foundation" species?

AARON ELLISON: "Eastern hemlock is slowly vanishing from North American forests as it is weakened and killed by a small insect, the hemlock wooly adelgid. I tell the story of multiple consequences of hemlock loss through Hemlock Hospice, a collaborative, outdoor site-specific sculpture installation co-developed with artist and designer David Buckley Borden, currently being exhibited at Harvard University's Harvard Forest. Hemlock Hospice uniquely blends science, art, and design to [1] respect eastern hemlock and its ecological role as a foundation forest species; [2] promote an understanding of the adelgid; and [3] encourage empathetic conversations among all the sustainers of and caregivers for our forests - ecologists and artists, foresters and journalists, naturalists and citizens - while fostering social cohesion around ecological issues. More expansively, Hemlock Hospice contextualizes hemlock decline in the broader context of climate change, local effects of our global economy on the natural world, and environmental impacts of our consumer culture. As a scientist, I study how our forests may respond to the loss of this foundation tree species, but as a human being, I cry, I mourn, and I look to the future for hope. Hemlock Hospice tells the story of eastern hemlock in a new way, communicating why so many scientists and poets care about it, and what its plight tells us about the future of our environment."

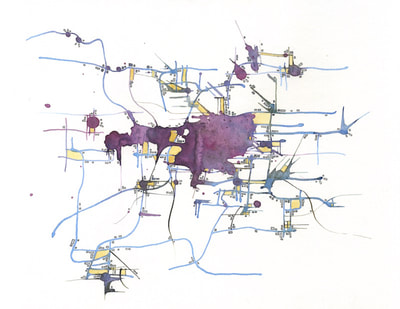

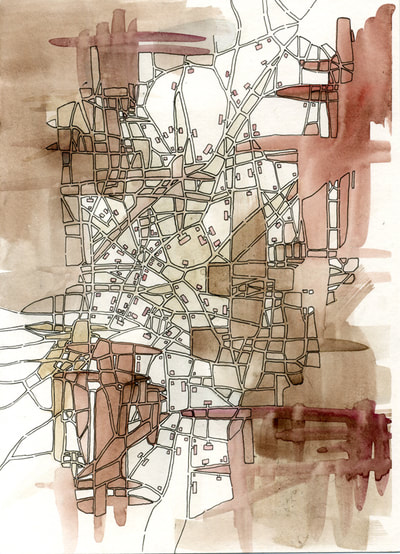

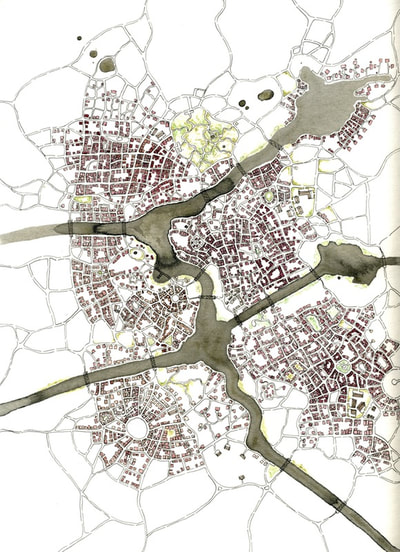

How do cities get their form, and how does that emergent process relate to how complex biological systems evolve?

EMILY GARFIELD: "I study both cities and natural objects and use that to structure my drawing explorations. Through drawing I refine and iterate upon my mental conception of how this growth happens. In practice, I create abstract drawings in pen and watercolor that follow procedural rules with hand-drawn execution, resulting in images that can be interpreted as maps or networks, but also veins, cells or biological forms."

x

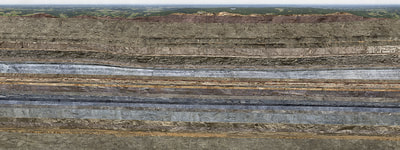

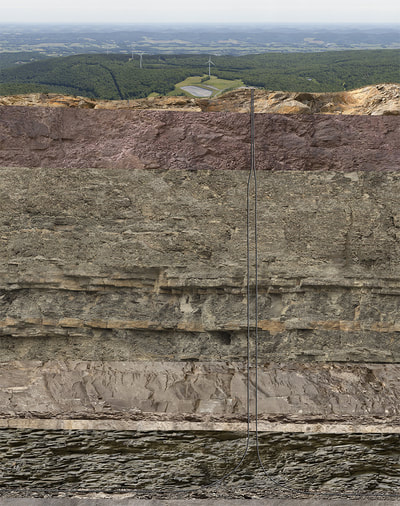

What does fracking look like?

JONATHON WELLS: "My search for the answer to what fracking looks like involves using my knowledge as a geologist, creativity as an artist, and skill as a photographer. The perspective of the final picture I create does not exist in reality. It is an image created in my mind as a geologist that I digitally composite using photographs on the computer. My perspective typically places emphasis on the greater context of what I am trying to show by extending the frame outward. After learning which types of sedimentary rock layers fill the basin, I photographed those same types of rocks where they were visible on the earth's surface, and then placed the photographs into the image. I then depicted the locations of eight different shale gas wells. If it were possible to split the earth crust apart and open up a view that is three miles deep and eight miles wide, then this is a generalization of what I believe one would see. I felt that it was important to show the entire scene at a scale of 1:1 without vertical or horizontal exaggeration. Imagery is important to help us understand an issue such as shale gas extraction or fracking. It is my hope that my interpretation of available geologic data and my artistic, photographic depiction of the earth's crust and shale gas wells is helpful to others who would like to know more about shale gas extraction/fracking."

JONATHON WELLS: "My search for the answer to what fracking looks like involves using my knowledge as a geologist, creativity as an artist, and skill as a photographer. The perspective of the final picture I create does not exist in reality. It is an image created in my mind as a geologist that I digitally composite using photographs on the computer. My perspective typically places emphasis on the greater context of what I am trying to show by extending the frame outward. After learning which types of sedimentary rock layers fill the basin, I photographed those same types of rocks where they were visible on the earth's surface, and then placed the photographs into the image. I then depicted the locations of eight different shale gas wells. If it were possible to split the earth crust apart and open up a view that is three miles deep and eight miles wide, then this is a generalization of what I believe one would see. I felt that it was important to show the entire scene at a scale of 1:1 without vertical or horizontal exaggeration. Imagery is important to help us understand an issue such as shale gas extraction or fracking. It is my hope that my interpretation of available geologic data and my artistic, photographic depiction of the earth's crust and shale gas wells is helpful to others who would like to know more about shale gas extraction/fracking."

x

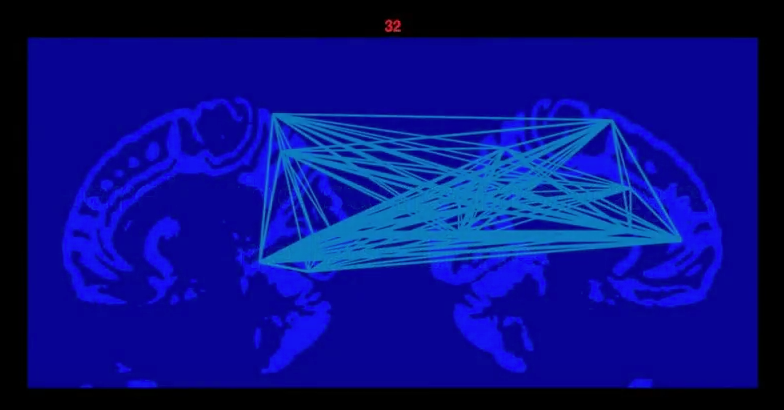

What is it about the brain that makes it the seat of consciousness?

DAN LLOYD: "I work at the multi-dimensional intersection of cognitive neuroscience, philosophical phenomenology, cognitive musicology, and data visualization/sonification. I start with phenomenology, the detailed anatomy of conscious experience as it has been excavated by philosophers like Husserl, Sartre, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Beauvoir. They outline the necessary structures of conscious experience and thereby specify what it is that a scientific theory of consciousness must explain. One of these necessary structures is temporality - our experience of the passage of time, duration, sequence, and change. I work with online data repositories like the Human Connectome Project to sift through terabytes of fMRI data to observe how the brain embeds its representation of the present in a detectable (and experienced) context of time. The observed patterns are complex (no surprise), which has led in two further directions. First, I conjecture that human brain dynamics are congruent with the dynamical structure of music, or to put it another way, music arose as a sensory structure modeled on the syntax of thought. Some of the salient temporal and tonal properties of world music reappear as global properties of the active brain. This finding invites a search for musical representations of brain data, the second main direction of my current research. This is data sonification, which along with visualization, offers an intuitive and informative representation of the gyrations of this most complex of systems, the brain, as it embodies the most complex of conscious beings, namely, us."

DAN LLOYD: "I work at the multi-dimensional intersection of cognitive neuroscience, philosophical phenomenology, cognitive musicology, and data visualization/sonification. I start with phenomenology, the detailed anatomy of conscious experience as it has been excavated by philosophers like Husserl, Sartre, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Beauvoir. They outline the necessary structures of conscious experience and thereby specify what it is that a scientific theory of consciousness must explain. One of these necessary structures is temporality - our experience of the passage of time, duration, sequence, and change. I work with online data repositories like the Human Connectome Project to sift through terabytes of fMRI data to observe how the brain embeds its representation of the present in a detectable (and experienced) context of time. The observed patterns are complex (no surprise), which has led in two further directions. First, I conjecture that human brain dynamics are congruent with the dynamical structure of music, or to put it another way, music arose as a sensory structure modeled on the syntax of thought. Some of the salient temporal and tonal properties of world music reappear as global properties of the active brain. This finding invites a search for musical representations of brain data, the second main direction of my current research. This is data sonification, which along with visualization, offers an intuitive and informative representation of the gyrations of this most complex of systems, the brain, as it embodies the most complex of conscious beings, namely, us."

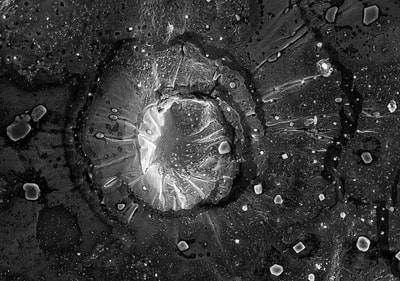

How can artistic thinking and procedures shift the visual outcomes of scientific photomicrography for aesthetic purposes?

ANASTASIA TYURINA: "My research involves aesthetic approaches to scientific photomicrography. Specifically, this project investigates the reinterpretation of photomicrographic images of micro-scale drops of water made by a scanning electron microscope (SEM), a tool that has expanded the boundaries of observation and representation of the micro world since it was introduced to scientific research in the mid-1960s. The primary purpose of my visual art project is to depict the inherent features of water that are invisible to the eye through using the SEM. To do so, I used the process of evaporation as an alternative and unusual artistic method of visually presenting the composition of water. My approach is unique in the specific way in which I use water to create images using the SEM. During experiments for my project, it became evident that the structure of water impurities is visually transformed after evaporation and reveals a unique connection between evaporation and solidification. This process of revealing the nature of water (water chemistry) allowed me to play with the process like an artist. As well as offering a visual engagement, the work offers an embodied engagement: an important connection to the material significance of water in our lives."

x

What do our genomes say about our biological health?

LYNN FELLMAN: "My work endeavors to make our gene stories understandable and meaningful. It is important for all of us - taxpayers and policy makers - to understand basic science concepts to guide smart strategies for health, economy, and our environment. The problem is getting the fundamentals across in a clear and engaging way. My solution combines accurate information with poetic visualization. Combining art and story to illuminate the beauty and benefit of genomic and evolutionary science is my passion as an artist and as a responsible citizen. To get the art and story right I study current scientific literature, attend science conferences, and work with scientists to understand their work. Then I write, design, and illustrate to explain what they do and why we should care. The outcome could be an art exhibit, animated video, or interactive eBook."

LYNN FELLMAN: "My work endeavors to make our gene stories understandable and meaningful. It is important for all of us - taxpayers and policy makers - to understand basic science concepts to guide smart strategies for health, economy, and our environment. The problem is getting the fundamentals across in a clear and engaging way. My solution combines accurate information with poetic visualization. Combining art and story to illuminate the beauty and benefit of genomic and evolutionary science is my passion as an artist and as a responsible citizen. To get the art and story right I study current scientific literature, attend science conferences, and work with scientists to understand their work. Then I write, design, and illustrate to explain what they do and why we should care. The outcome could be an art exhibit, animated video, or interactive eBook."

x

How can we lower the carbon footprint of art production?

DANIELLE SIEMBIEDA: "For the past several years I have been working on a process of lowering the carbon footprint of art production through the project Art Inspector: Saving the Earth by Changing Art. This entails a three part solution: [1] Healthy Art Program (Education), [2] Green Certification (Third Party Inspections on Life Cycle Assessment), and [3] Economy Reform (Changing the supply/demand of the field). This project has been funded primarily through municipal governments who see the art communities and their practices as potentially hazardous to their health and the environment. This project is part social practice, part institutional critique, and part intervention. It uses energy auditing systems, life cycle assessment and material engineering."

DANIELLE SIEMBIEDA: "For the past several years I have been working on a process of lowering the carbon footprint of art production through the project Art Inspector: Saving the Earth by Changing Art. This entails a three part solution: [1] Healthy Art Program (Education), [2] Green Certification (Third Party Inspections on Life Cycle Assessment), and [3] Economy Reform (Changing the supply/demand of the field). This project has been funded primarily through municipal governments who see the art communities and their practices as potentially hazardous to their health and the environment. This project is part social practice, part institutional critique, and part intervention. It uses energy auditing systems, life cycle assessment and material engineering."

x

How does texting effect language and communication?

ALYCIA THOMPSON: "Texting has become our way of communicating. To help with the lack of tonal changes we would get with listening to a voice, emojis were created. My work shows people expressing different emotions in different situations and what emoji might be used with that given emotion and how they play off each other in different settings."

ALYCIA THOMPSON: "Texting has become our way of communicating. To help with the lack of tonal changes we would get with listening to a voice, emojis were created. My work shows people expressing different emotions in different situations and what emoji might be used with that given emotion and how they play off each other in different settings."

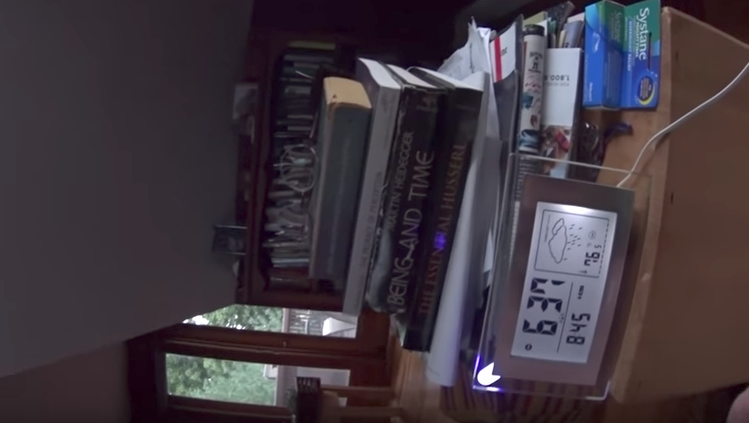

How can we capture the fleeting thoughts that continually race through our minds,

at the edge of consciousness?

at the edge of consciousness?

IAN GIBBINS: "Having been a neuroscientist for 35 years and a professor of anatomy for 20 of them, I am now a widely-published poet, electronic musician, and video artist. My deep knowledge of the brain and the body informs the written, visual, and audio language I use in writing and performing poetry across diverse formats. As a neuroscientist, much of my research was done at the microscopic level, examining how nerve cells communicate with other. I used everything from electron microscopes to recordings of the activity of single nerve cells. As a teacher of anatomy, I came to know the structure of the human body literally from inside out. Along the way, I acquired the language to describe what most people have never seen beneath our skins, as well as the understanding that what we consciously experience is a mental construct, reliable enough much of the time, hopelessly wrong at others. Over the years, my poems have explored these issues to varying degrees, often explicitly drawing on my scientific work and language. In my current practice, video poetry allows me to fuse text, audio, and moving image to present glimpses of the barely-conscious in unique ways. Using combinations of real-world imagery and animations, electronic and environmental sounds, original and found text as appropriate, I can generate microcosms of experience that people generally recognize and connect with, even though the details of any particular piece of work may seem obscure. My videos have been published in various online literary magazines, and have been shown in galleries, public art works, and in international festivals."

x

How do we engage culturally with technological intersections of living and electronic systems?

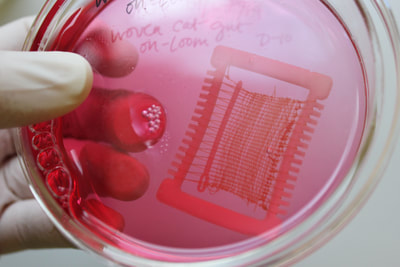

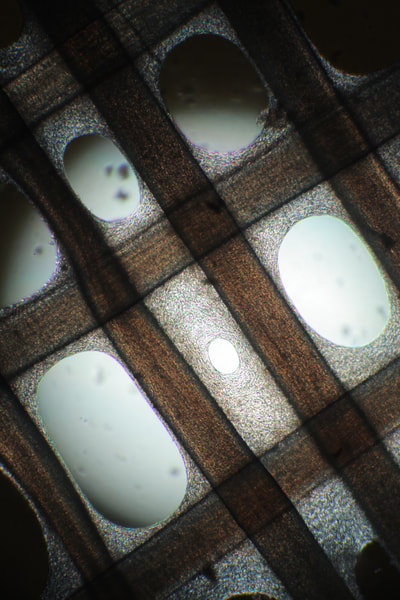

WHITEFEATHER HUNTER: "My BioArt practice is positioned within the context of craft, via material investigations of the aesthetic and technological potential of bodily and vital materials. Some previous projects include: traditional textile constructions of human hair; rogue taxidermy sculpture with recycled fabrics/fur, found flesh and bone; digital representations of the body absent in the digital world; and, mammalian tissue engineering on textile scaffolds. I also hack/build electronics, use web-based platforms to generate new mythologies via viral and interactive media, and work in narrative video and approaches performance as embodied research in both the laboratory and the landscape. My current research-creation practice is focused on the material applications of living systems and the haptic intelligence of microorganisms and their interaction with machines."

WHITEFEATHER HUNTER: "My BioArt practice is positioned within the context of craft, via material investigations of the aesthetic and technological potential of bodily and vital materials. Some previous projects include: traditional textile constructions of human hair; rogue taxidermy sculpture with recycled fabrics/fur, found flesh and bone; digital representations of the body absent in the digital world; and, mammalian tissue engineering on textile scaffolds. I also hack/build electronics, use web-based platforms to generate new mythologies via viral and interactive media, and work in narrative video and approaches performance as embodied research in both the laboratory and the landscape. My current research-creation practice is focused on the material applications of living systems and the haptic intelligence of microorganisms and their interaction with machines."