Ian Gibbins

Interview by Julia Brennan, Lafayette College SciArt Intern

JB: In projects such as "The Microscope Project," How Things Work, and Microscope Music, you’ve created chandeliers, poems, and music focused around a common piece of lab equipment, the microscope. What draws you to continually come back to the microscope?

IG: Having spent most of my working life around microscopes, they naturally feed into my creative output.

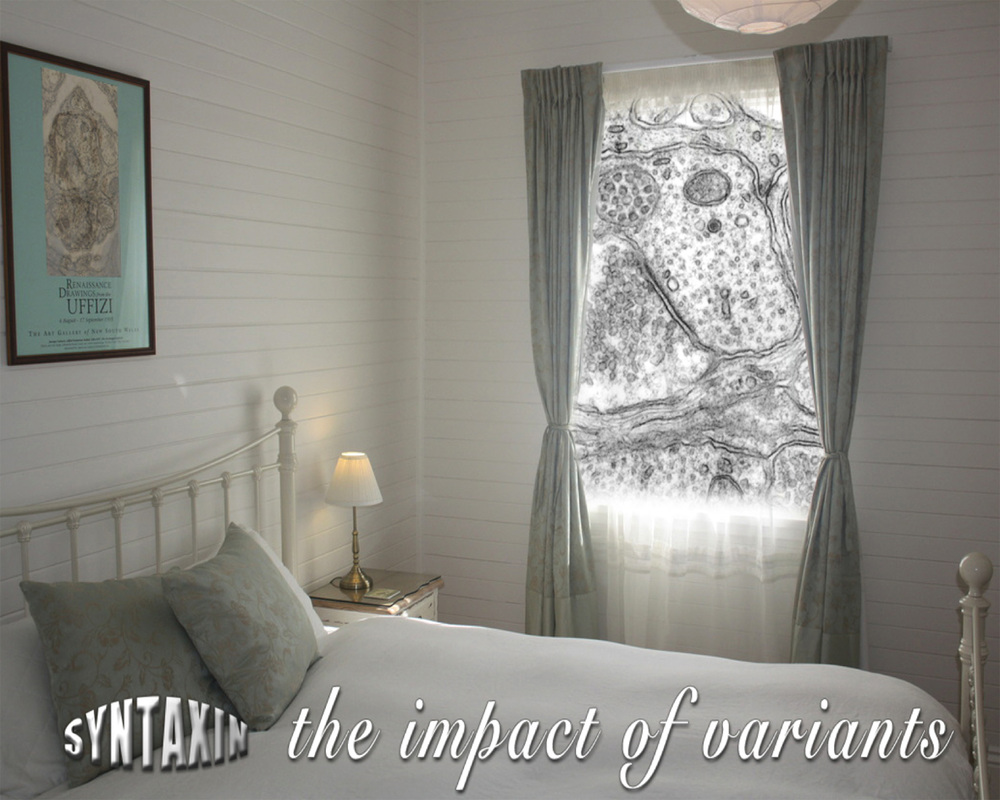

How Things Work (poetry and images) and Microscope Music (poetry and electronic music) were both parts of “The Microscope Project,” a collaborative art-science exhibition we did in 2014. During my career as a neuroscientist, my main experimental technique was microscopy. I first learnt to use an electron microscope in 1974, while still an undergraduate student. Along the way, I used and helped develop new techniques for using a wide range of microscopes, including one that builds up images of living cells one photon at a time. The amazing thing about microscopy is that every time you operate one, your perceptions of the world are challenged: just what is it you are observing? Why does it look that way? Is the instrument working properly? Or is my visual system missing something important?

Interview by Julia Brennan, Lafayette College SciArt Intern

JB: In projects such as "The Microscope Project," How Things Work, and Microscope Music, you’ve created chandeliers, poems, and music focused around a common piece of lab equipment, the microscope. What draws you to continually come back to the microscope?

IG: Having spent most of my working life around microscopes, they naturally feed into my creative output.

How Things Work (poetry and images) and Microscope Music (poetry and electronic music) were both parts of “The Microscope Project,” a collaborative art-science exhibition we did in 2014. During my career as a neuroscientist, my main experimental technique was microscopy. I first learnt to use an electron microscope in 1974, while still an undergraduate student. Along the way, I used and helped develop new techniques for using a wide range of microscopes, including one that builds up images of living cells one photon at a time. The amazing thing about microscopy is that every time you operate one, your perceptions of the world are challenged: just what is it you are observing? Why does it look that way? Is the instrument working properly? Or is my visual system missing something important?

“The Microscope Project” was created when several instruments in the microscopy facility I managed at Flinders University were decommissioned and were going to be dumped. Although they were well and truly superseded, they actually worked, and it seemed such a waste to turn them into scrap, especially two old scanning electron microscopes that crossed the transition from analogue to digital electronics. My friend and colleague, Catherine Truman, was artist-in-residence with me at the time, and we came up with the idea of re-imagining the lives of the instruments and the people who designed, built or operated them. It was a wonderful project that connected between technology and people, basic research and creativity, in ways we never dreamt of when we began. Indeed, some of my research colleagues became quite emotional when they saw they way we’d exposed the human side of all this technology.

As well as the texts I produced for How Things Work, I’ve had several other poems and videos published that have their genesis in microscopy, neuroscience and anatomy.

JB: Some of your work seems to study the influence of the written word on communication, such as Tramstop 6, How to Read, and, on a slightly more abstract level, Game Over. As a poet, were there any experiences and/or ideas that influenced this theme for you?

IG: My creative writing covers many different styles, but one underlying premise is that, for all its undoubted value, language fails us all too often, like, you know, ummm... those occasions when we are 'lost for words'. Modern neuroscience gives us a rationale for this: many areas of brain activity, such as those initiating and controlling movement, our sense of our own body and our location in the world, and our emotional status, are not tightly linked into pathways generating and storing explicit verbal knowledge.

As well as the texts I produced for How Things Work, I’ve had several other poems and videos published that have their genesis in microscopy, neuroscience and anatomy.

JB: Some of your work seems to study the influence of the written word on communication, such as Tramstop 6, How to Read, and, on a slightly more abstract level, Game Over. As a poet, were there any experiences and/or ideas that influenced this theme for you?

IG: My creative writing covers many different styles, but one underlying premise is that, for all its undoubted value, language fails us all too often, like, you know, ummm... those occasions when we are 'lost for words'. Modern neuroscience gives us a rationale for this: many areas of brain activity, such as those initiating and controlling movement, our sense of our own body and our location in the world, and our emotional status, are not tightly linked into pathways generating and storing explicit verbal knowledge.

Paradoxically, the creative arts, including poetry, have the capacity to put into words what cannot be said, or to create images of what cannot be seen. So my works tries to capture and somehow make sense of those fleeting, fragmentary thoughts that continually flit through your mind, the things you don’t quite see out the corner of your eye, the voices you can’t quite hear through the enveloping buzz, memories that may or may not be reliable. Again, the neuroscience confirms what artists have always known: through all this uncertainty and imprecision, we are driven to create narrative; we cannot help trying to put ourselves in the picture.

As a poet, I’m not interested in describing pastoral scenes or revealing my inner self. Most of my work is really fiction: invented scenes, characters, voices, stories. But like all fiction, it must be rooted in my own experience, environment, and emotional state. On the other hand, I really enjoy minimising these personal influences, by using rules to generate or limit text, especially text sampled from public domain sources such as newspapers. The work then lays down a challenge to the reader to build their own narrative from the fragments I assemble. This approach succeeds much more often than many people would expect.

JB: Translating the Body and The Filtered Body were both projects studying the representation of the body from the perspective of students. As a retired anatomy professor, was there anything you learned from this project that surprised you?

IG: These projects were done in collaboration with then artist-in-residence, Catherine Truman, over a couple of years before I retired. We share a long-standing interest in how the body is represented across diverse media, including textbooks and other teaching resources, and then how those representations become internalized into personalized knowledge. When studying anatomy, complex transformations take place between the specific and the general, the external and internal. The question is: whose body do you learn? Catherine was especially interested in how the students physically and emotionally handled the specimens in the anatomy teaching laboratory, as well as how I moved through the complicated architectural, intellectual and cultural spaces of this learning environment.

As a poet, I’m not interested in describing pastoral scenes or revealing my inner self. Most of my work is really fiction: invented scenes, characters, voices, stories. But like all fiction, it must be rooted in my own experience, environment, and emotional state. On the other hand, I really enjoy minimising these personal influences, by using rules to generate or limit text, especially text sampled from public domain sources such as newspapers. The work then lays down a challenge to the reader to build their own narrative from the fragments I assemble. This approach succeeds much more often than many people would expect.

JB: Translating the Body and The Filtered Body were both projects studying the representation of the body from the perspective of students. As a retired anatomy professor, was there anything you learned from this project that surprised you?

IG: These projects were done in collaboration with then artist-in-residence, Catherine Truman, over a couple of years before I retired. We share a long-standing interest in how the body is represented across diverse media, including textbooks and other teaching resources, and then how those representations become internalized into personalized knowledge. When studying anatomy, complex transformations take place between the specific and the general, the external and internal. The question is: whose body do you learn? Catherine was especially interested in how the students physically and emotionally handled the specimens in the anatomy teaching laboratory, as well as how I moved through the complicated architectural, intellectual and cultural spaces of this learning environment.

We learnt a lot about how the students perceive and navigate this environment, why they focus on particular types of specimens, who they choose to sit next to and why. The central role of touch, the ability to handle real anatomical specimens, to understand their weight and materiality and texture and more, emerged as a key experiential element of the learning experience of many students. From understanding this, I became even more attuned of the performative component of my teaching, not least because by then I was being projected onto giant video screens around the classroom and via video links to remote teaching sites. Thus, I became highly aware of what I sound like, what I look like, how I move, or not. In turn, this awareness has fed positively into my poetry performance technique.

JB: What are you working on right now?

IG: Right now, I don’t have any major specific projects on the go. I recently completed some commissioned work including an installation piece and a couple of videos (“situs inversus”) for an art-science exhibition, “Body of Evidence,” at the Adelaide Convention Centre: one video-poem was projected onto the windows of the building, with a different version on a giant LED screen, which was amazing to see! I’ve also had a video-poem commissioned by the Adelaide City Council which will be projected onto the side of a building in the main downtown shopping strip.

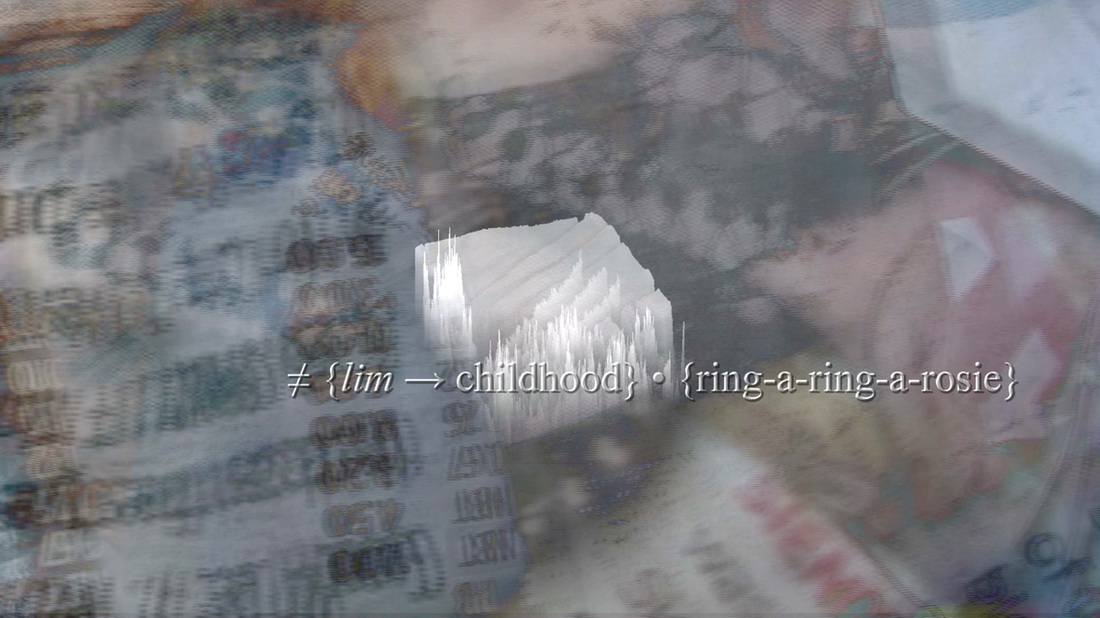

Several of my poems are coming out in various journals over the next few months, all with some sort of science influence. One of them is written in a pseudo computer programming language I more or less invented, and a video poem in which the text is translated into mathematical expressions (“accidentals , recalculated”) was just announced as a finalist in the 2016 Carbon Culture Poetry Film Prize.

IG: Right now, I don’t have any major specific projects on the go. I recently completed some commissioned work including an installation piece and a couple of videos (“situs inversus”) for an art-science exhibition, “Body of Evidence,” at the Adelaide Convention Centre: one video-poem was projected onto the windows of the building, with a different version on a giant LED screen, which was amazing to see! I’ve also had a video-poem commissioned by the Adelaide City Council which will be projected onto the side of a building in the main downtown shopping strip.

Several of my poems are coming out in various journals over the next few months, all with some sort of science influence. One of them is written in a pseudo computer programming language I more or less invented, and a video poem in which the text is translated into mathematical expressions (“accidentals , recalculated”) was just announced as a finalist in the 2016 Carbon Culture Poetry Film Prize.

Ian Gibbin is based in Adelaide, Australia.

Find Ian online:

Website: www.iangibbins.com.au

Facebook: www.facebook.com/IanGibbins.poetry.music.science

Viemo: vimeo.com/iangibbins

Bandcamp: iangibbins.bandcamp.com

Find Ian online:

Website: www.iangibbins.com.au

Facebook: www.facebook.com/IanGibbins.poetry.music.science

Viemo: vimeo.com/iangibbins

Bandcamp: iangibbins.bandcamp.com