Henry F. Brown

Interview with Julia Brennan, Lafayette College SciArt Intern

JB: Your work studies the influence of perception on information and imagery, and your recent series, “Paving the Way,” seems to expand on this idea by not only examining perception but transmission and how the act of transmission impacts the information being communicated.

In a field so reliant on people’s perception and recognition of imagery, do you push to ensure the imagery and information you use in your work eventually becomes recognizable by the viewer or do you embrace a work’s potential to be abstract?

HB: Rather than looking at realism and abstraction as opposites, I pull apart photographic images to reveal the abstract experience inherent within viewing an image. I really focus on the perceptions at work in image construction, both in physically making the image as well as within the human eye. I try to call attention to the human element, both biological and subconscious, that is able to see image and meaning within patterns of pigment. Not only do I want the viewer to see past the imagery in my work to look at the physical pieces that construct it, I want the viewer to realize that his or her gaze is also a continuing process of physical and conceptual image-making.

Interview with Julia Brennan, Lafayette College SciArt Intern

JB: Your work studies the influence of perception on information and imagery, and your recent series, “Paving the Way,” seems to expand on this idea by not only examining perception but transmission and how the act of transmission impacts the information being communicated.

In a field so reliant on people’s perception and recognition of imagery, do you push to ensure the imagery and information you use in your work eventually becomes recognizable by the viewer or do you embrace a work’s potential to be abstract?

HB: Rather than looking at realism and abstraction as opposites, I pull apart photographic images to reveal the abstract experience inherent within viewing an image. I really focus on the perceptions at work in image construction, both in physically making the image as well as within the human eye. I try to call attention to the human element, both biological and subconscious, that is able to see image and meaning within patterns of pigment. Not only do I want the viewer to see past the imagery in my work to look at the physical pieces that construct it, I want the viewer to realize that his or her gaze is also a continuing process of physical and conceptual image-making.

As you mentioned, I'm interested in how transmission impacts information, and the heart of that is in the material transformation that various technologies enact upon the information being transmitted. That draws me to technologies of image-making, everything from traditional printmaking to electron microscopy, LCD monitors, the Hubble telescope, and so on. I use these tools to create artwork by engaging with their processes of translation, by pulling apart information and piecing it back together. Whether the final piecing-together results in a legible image isn't predetermined. It's important to me to let the process of creating the piece speak for itself, and sometimes the process and the image are in dialogue and other times the materials and the viewer's experience are in dialogue - the form comes out of those relationships.

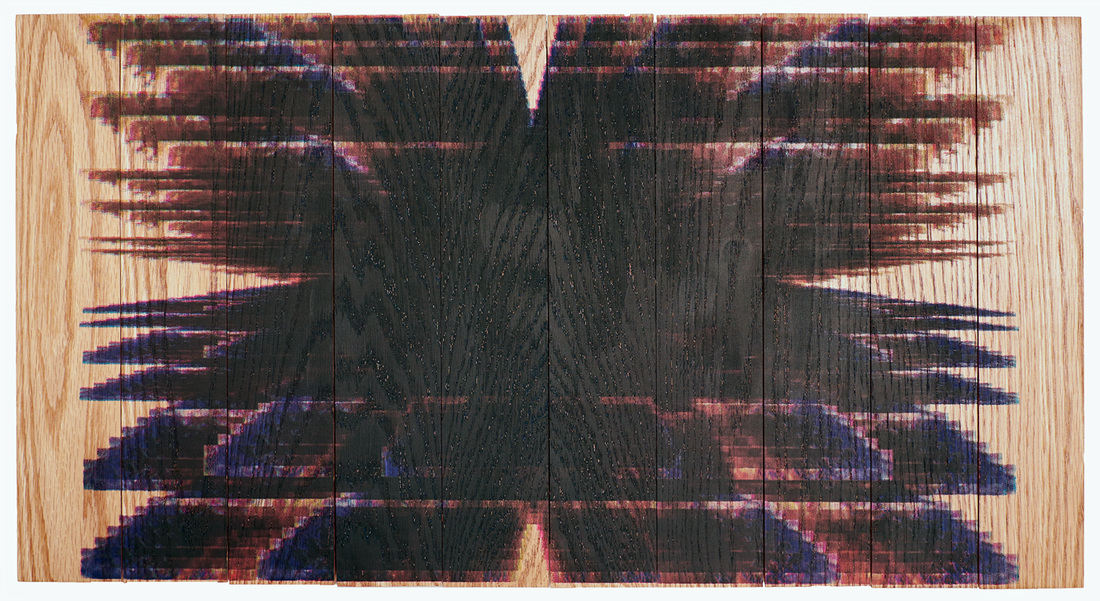

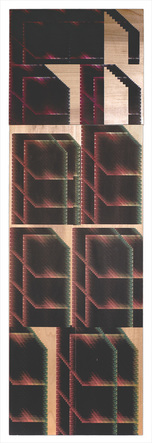

In the pieces Waterfall and Red Shift I deconstructed the source imagery, Hubble telescope photographs, by digitally cropping and multiplying one small piece of the image. By continuing the process of repeating the image, cropping it, then repeating and flattening again, I allowed the imagery to find form through the process. This path of deconstruction and reconstruction created the geometric forms that are printed on the surface of the wood. What I'm looking for is for the content and material of the surface pattern to interact with the physical support to question the duality of surface and structure.

In the pieces Waterfall and Red Shift I deconstructed the source imagery, Hubble telescope photographs, by digitally cropping and multiplying one small piece of the image. By continuing the process of repeating the image, cropping it, then repeating and flattening again, I allowed the imagery to find form through the process. This path of deconstruction and reconstruction created the geometric forms that are printed on the surface of the wood. What I'm looking for is for the content and material of the surface pattern to interact with the physical support to question the duality of surface and structure.

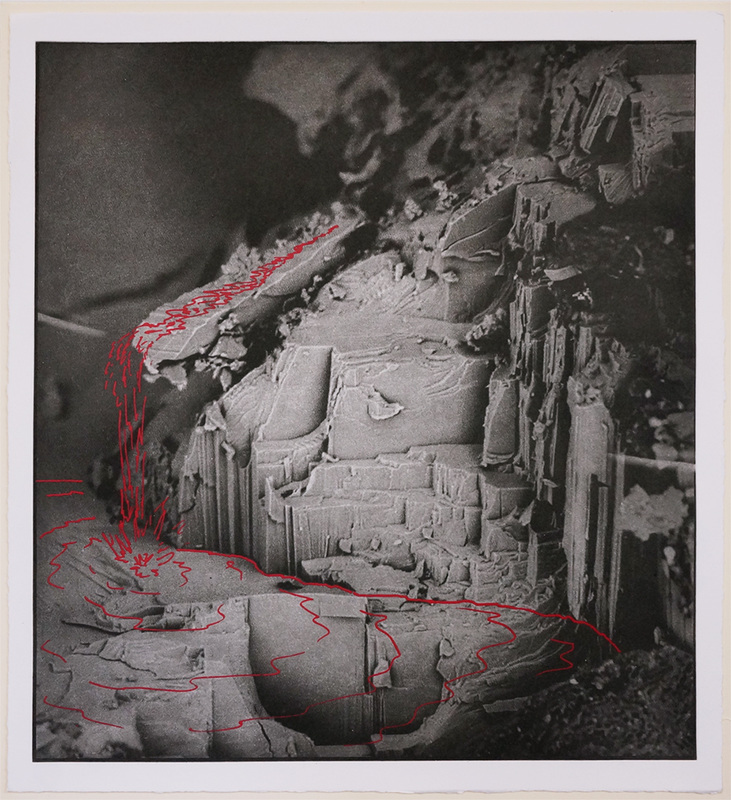

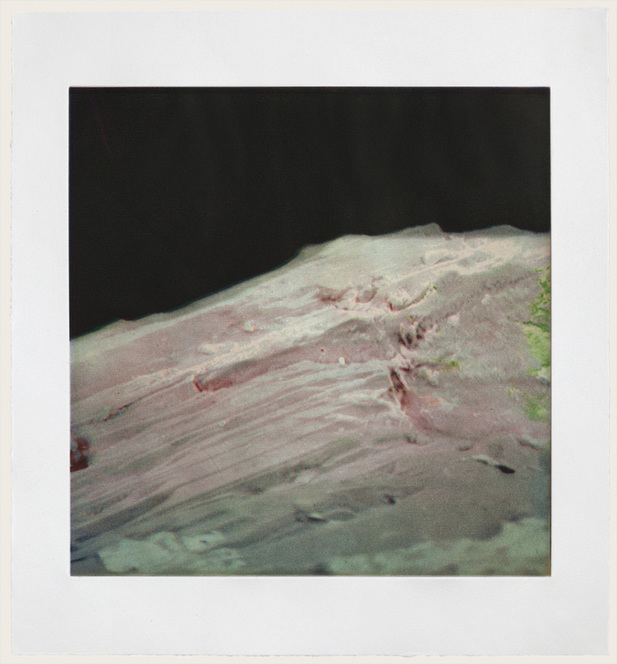

On the other hand, in Paving The Way I was attempting to transform real yet inaccessible places within a microscope into accessible and intangible spaces in the mind of the viewer. I took the source micrographs, and I was blown away by the huge shift in scale, by the incredible resolution, and the ease with which the images clicked into my mind as landscapes. In one way they are a landscape, just mineral formations, but on an inaccessible scale. It was the abstractness of the scale shift coming into contact with my natural instinct or desire to see landscape spaces that opened up the potential for the fictional narrative that takes place in the portfolio.

Whatever the image-making tool might be - electron microscope, a copper plate, or a paint brush - it's the meeting point of what we want to see and how we are able see. I find abstraction by exploring the physical transformations that enable the transmission of information.

Whatever the image-making tool might be - electron microscope, a copper plate, or a paint brush - it's the meeting point of what we want to see and how we are able see. I find abstraction by exploring the physical transformations that enable the transmission of information.

Waterfall (2013). 45" by 14". Silkscreen and shellac on wood.

Waterfall (2013). 45" by 14". Silkscreen and shellac on wood.

JB: What experiences and/or ideas influenced the manifestation of this theme for you?

HFB: Growing up in New York City had a huge influence on the way I look at the materials and processes of making art. Anyone who's spent enough time walking around NYC knows the cement sidewalk squares, the subway grates, bricks in brownstones, thousands of windows, the tiles in the subway station - all of these repeating patterns of materials that piece together the surface of such a physically and culturally massive place. As a kid I enjoyed looking at all those patterns on the surface and imagining the structures that they hid beneath them. I loved thinking about the pipes and cable lines that I couldn't see, and the subway lines reaching out under the city and under the rivers to connect all of the people across the city. I think that's where I first started to look at the patterns of materials we use to build and how they simultaneously enable and are formed by our cultural and social structures. That was a big thing for me - noticing that the forms and materials that make the city could also show the human needs that created it. I was amazed to think that even the modular, standardized, usually grey materials that cover the city could reveal a glimpse of the hands and minds that put them all together. Behind all of the poured and extruded industrial forms is a human need, or more slightly accurately 10 million human needs, that determine the forms and pathways those materials take.

JB: You’ve done a lot of work with community outreach, from holding community printmaking classes to beginning your own printmaking studio, Overpass Projects. How do you see SciArt broadening the scope of inquiry and curiosity not only for scientists and artists, but also for the community as a whole?

HFB: We often take the view that science and art are diametrically opposed pursuits, and while I don't think things are as clear cut as that, there is a productive way of viewing that duality. In a general sense, I see science as a way of learning about the world by looking outward, while art strives to achieve the same goal by looking inward. Neither approach on it's own can fully delineate the pieces that make up our place within the world, but hopefully by unifying the processes and perspectives of both fields we can can start to see a more complete picture.

HFB: Growing up in New York City had a huge influence on the way I look at the materials and processes of making art. Anyone who's spent enough time walking around NYC knows the cement sidewalk squares, the subway grates, bricks in brownstones, thousands of windows, the tiles in the subway station - all of these repeating patterns of materials that piece together the surface of such a physically and culturally massive place. As a kid I enjoyed looking at all those patterns on the surface and imagining the structures that they hid beneath them. I loved thinking about the pipes and cable lines that I couldn't see, and the subway lines reaching out under the city and under the rivers to connect all of the people across the city. I think that's where I first started to look at the patterns of materials we use to build and how they simultaneously enable and are formed by our cultural and social structures. That was a big thing for me - noticing that the forms and materials that make the city could also show the human needs that created it. I was amazed to think that even the modular, standardized, usually grey materials that cover the city could reveal a glimpse of the hands and minds that put them all together. Behind all of the poured and extruded industrial forms is a human need, or more slightly accurately 10 million human needs, that determine the forms and pathways those materials take.

JB: You’ve done a lot of work with community outreach, from holding community printmaking classes to beginning your own printmaking studio, Overpass Projects. How do you see SciArt broadening the scope of inquiry and curiosity not only for scientists and artists, but also for the community as a whole?

HFB: We often take the view that science and art are diametrically opposed pursuits, and while I don't think things are as clear cut as that, there is a productive way of viewing that duality. In a general sense, I see science as a way of learning about the world by looking outward, while art strives to achieve the same goal by looking inward. Neither approach on it's own can fully delineate the pieces that make up our place within the world, but hopefully by unifying the processes and perspectives of both fields we can can start to see a more complete picture.

|

No matter which discipline one is involved with, it's in the real-world application that ultimately places value on the output. This is why institutional and individual outreach to communities is so important. Without response and participation, the conversation about who we are and how we live in this world simply becomes a sermon. Thankfully there are so many arts and science organizations ranging from large institutions to small groups of amazing individuals that push to connect the public with the research and results of both fields, and to allow the public to participate in its production. It really is those institutions and organizations that allow a reciprocating conversation to take place, and more importantly to take place in the public sphere.

JB: What are you currently working on?

HFB: I've been making progress on a series of paintings called Chevrolet Transmissions that I began while on a residency in the Southwest this past fall. They're photo-silkscreens on board, and they start as photographs that I took from inside a Chevrolet Express van. After driving past hundreds of cell phone and radio transmission towers I got to thinking about how such tall, seemingly silent structures are constantly emitting, receiving, relaying microwave and radio wave transmissions. The movement of all these invisible energetic waves that constantly surround us and pass through us fascinated me, especially thinking about how all those waves are packed with information. I saw a connection between the constant forward movement of the van, the acoustic bubble of being inside a vehicle, and the radio waves emitting from the towers that clicked for me and sparked the project. |

Now I'm back in Providence and for the near future Overpass Projects is going to be taking up most of my time and focus. My business partner and former RISD classmate Julia Samuels and I have recently finished the construction phase of the printshop, and are now starting to tackle the publishing side. We've invited a few artists to come work with us to produce some print editions that will be shown at The Wurks Gallery in Providence, RI in October.

View more of Henry's work on his websites:

www.henryfeltonbrown.com

www.overpassprojects.com

Follow Henry on Instagram: @overpassprojects & @hankattak

www.henryfeltonbrown.com

www.overpassprojects.com

Follow Henry on Instagram: @overpassprojects & @hankattak