"Gut Instinct:

Art, Design, and the Microbiome"

a virtual exhibition curated by Charissa N. Terranova and David R. Wessner

during their participation in The Bridge 2015-2016, SciArt Center's residency program

Art, Design, and the Microbiome"

a virtual exhibition curated by Charissa N. Terranova and David R. Wessner

during their participation in The Bridge 2015-2016, SciArt Center's residency program

The digestive systems of mammals are brimming with internal dwellers. Our guts are teeming with billions of microbes! Yet, it usually is a happy coexistence.

We live in a state of mutual symbiosis with these inhabitants: in an alimentary feedback loop, we nurture them and they nurture us. While we provide a hospitable environment in which they can live, they are necessary for our holistic well-being. Various bacteria aid in the digestion of the food we eat. Bacteria like Escherichia coli produce vitamin K and B-complex vitamins for us. Increasing evidence indicates that the microbes in us may affect the functioning of our immune system and our mental health. The microbiota (the actual bacteria) and the microbiome (their DNA) clearly contribute to our well-being.

Gut Instinct: Art, Design, and the Microbiome gathers artists, architects, and scientists to give real and metaphorical shape to the human microbiome. Art theorist and critic Charissa Terranova and microbiologist Dave Wessner have teamed up to curate an on-line exhibition in particular on the brain-gut axis: how the bacteria in the gut affects mood.

In parsing this head-stomach federation, Terranova and Wessner show how rational thinking is connected to the intestines. They reveal that consciousness and mind are seated in the brain as well as the GI tract. By connection, ratiocination unfolds across the body and is made possible by a full battery of the senses. Understanding “mind” in terms of the “gut-brain axis” shows how consciousness is more than quiet brainfed rumination: putative mind is rooted in the behavior of our gut bacteria as well. Mind is thus a matter of seeing, smelling, and tasting as well – anything that brings our gut-brain axis to a joyful equilibrium.

That said, the exhibition “visualizes” the microbiome both scientifically and aesthetically. Here Terranova and Wessner deploy “visualization” in the most capacious sense of the term, as it describes scientific imagery as well as artistic interpretations of the scientific concepts, in this instance the microbiome, microbiota, and the brain-gut axis, i.e. gut bacteria and the cybernetic connections between the brain and intestinal tract. The show includes vibrant and colorful imagery of the microbiota in action, experimental uses of synthetic biology in architectural design, and curious and mind-opening microbiomic extrapolations by new media artists. The art in this exhibition dwells on science, technology, art, design, and a full array of senses.

We live in a state of mutual symbiosis with these inhabitants: in an alimentary feedback loop, we nurture them and they nurture us. While we provide a hospitable environment in which they can live, they are necessary for our holistic well-being. Various bacteria aid in the digestion of the food we eat. Bacteria like Escherichia coli produce vitamin K and B-complex vitamins for us. Increasing evidence indicates that the microbes in us may affect the functioning of our immune system and our mental health. The microbiota (the actual bacteria) and the microbiome (their DNA) clearly contribute to our well-being.

Gut Instinct: Art, Design, and the Microbiome gathers artists, architects, and scientists to give real and metaphorical shape to the human microbiome. Art theorist and critic Charissa Terranova and microbiologist Dave Wessner have teamed up to curate an on-line exhibition in particular on the brain-gut axis: how the bacteria in the gut affects mood.

In parsing this head-stomach federation, Terranova and Wessner show how rational thinking is connected to the intestines. They reveal that consciousness and mind are seated in the brain as well as the GI tract. By connection, ratiocination unfolds across the body and is made possible by a full battery of the senses. Understanding “mind” in terms of the “gut-brain axis” shows how consciousness is more than quiet brainfed rumination: putative mind is rooted in the behavior of our gut bacteria as well. Mind is thus a matter of seeing, smelling, and tasting as well – anything that brings our gut-brain axis to a joyful equilibrium.

That said, the exhibition “visualizes” the microbiome both scientifically and aesthetically. Here Terranova and Wessner deploy “visualization” in the most capacious sense of the term, as it describes scientific imagery as well as artistic interpretations of the scientific concepts, in this instance the microbiome, microbiota, and the brain-gut axis, i.e. gut bacteria and the cybernetic connections between the brain and intestinal tract. The show includes vibrant and colorful imagery of the microbiota in action, experimental uses of synthetic biology in architectural design, and curious and mind-opening microbiomic extrapolations by new media artists. The art in this exhibition dwells on science, technology, art, design, and a full array of senses.

Featured on WNYC public radio

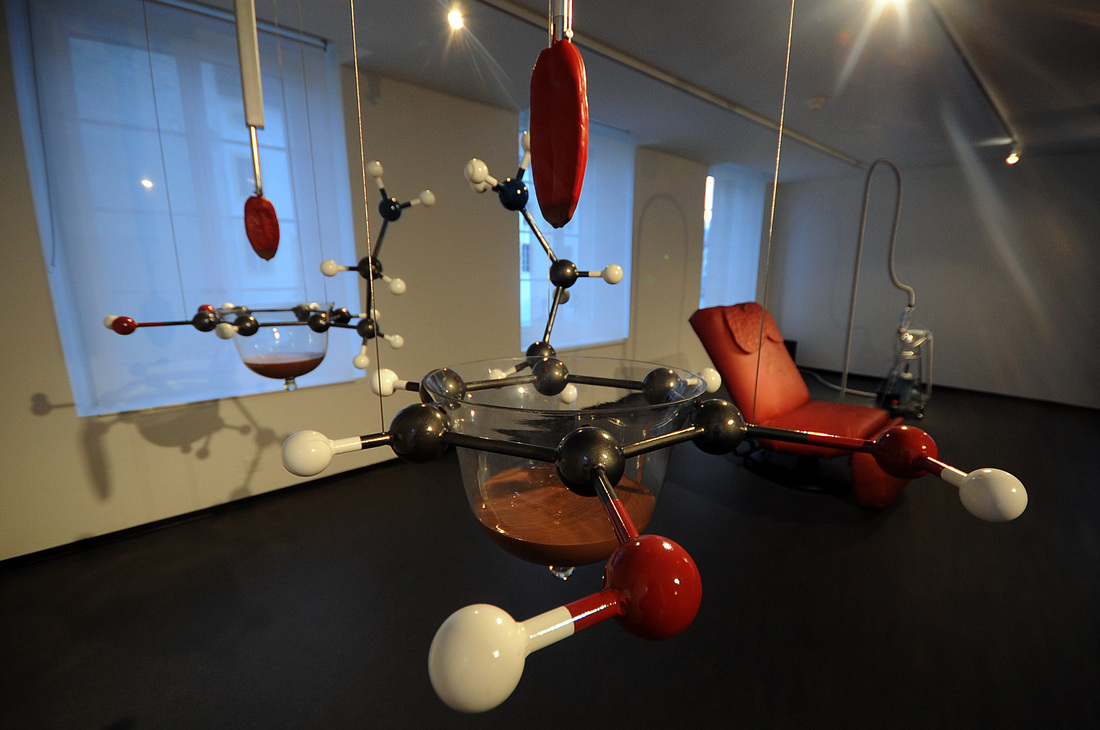

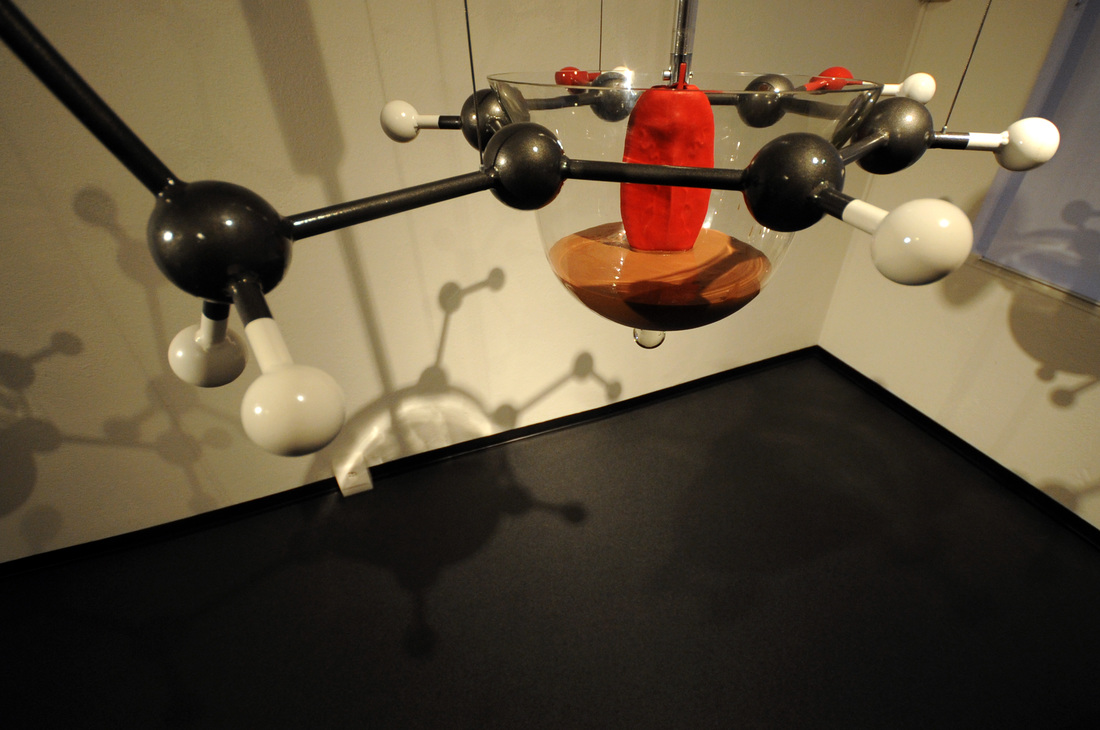

Ken Rinaldo is internationally recognized for his interactive installations blurring the boundaries between the organic and inorganic and speaking to the co-evolution between living and evolving technological cultures. His work interrogates these fuzzy boundaries and posits that as new machinic and algorithmic species arise, that we need to better understand the complex intertwined ecologies that machinic semi-living species create. Focused on trans-species communication he seeks to empower animal, insect, bacterial and emergent machine intelligences. Rinaldo's works have been commissioned/displayed in over 30 countries earning him an Award of Distinction at Ars Electronica Austria and first prize for Vida 3.0 for Autopoiesis.

The Enteric Consciousness is an installation focused on the conscious microbiome. A large glass stomach is filled with living bacteria (lactobacillus Acidophilus) and activates a large robotic chair in the shape of a giant tongue. The tongue chair gives you a comforting 15-minute massage, only if the bacterial cultures within the artificial stomach are living. This work explores our sense of touch and corporeal experience with bacterial cultures driving the function of the robot. Two robotic tongues also dip into chocolate and cheese pools in glass containers, suspended with steel dopamine molecules. Dopamine mediates the subjective experience of pleasure in humans and chocolate boosts antidepressant serotonin and stimulates secretions of endorphins that create pleasurable sensations in both brain and gut. Electronic peristaltic pumps replicate natural gut action, moving cooling water through the microbiome bacterial cultures in the glass stomach, to keep the bacteria cool, happy and healthy in this symbiotic system.

Premiere of Enteric Consciousness by Ken Rinaldo at LA MAISON d’AILLEURS, MUSEUM OF SCIENCE FICTION, UTOPIA & EXTRAORDINARY JOURNEYS Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland Sept-Mar 2010-11 commissioned by Director Patrick Gyger. Photo Joanna Avril.

What is the microbiome?

|

Permission to use granted by Dr. Jack Gilbert and Argonne National Laboratory

|

What is the microbiome? To fully appreciate Gut Instinct, we really should begin by addressing this fundamental question. Although use of the word “microbiome” probably dates to the mid-20th century, individuals often point to Joshua Lederberg’s 2001 use of it as the modern birth of the word. He defined it as the bacterial and viral genomes present in our bodies. Today, scientists and non-scientists alike generally use “microbiome” to refer more broadly to the entire microbial community, organisms and their genomes, occupying a defined habitat.

In this video, featuring Dr. Jack Gilbert, a microbial ecologist at the University of Chicago and Argonne National Laboratory, we learn more about the importance of the human microbiome. As Dr. Gilbert notes, understanding how we acquire our microbiome, how our external surroundings affect our microbiome, and how our bodies interact with the microbiome may dramatically alter how we think about human health. |

ANNA DUMITRIU

Anna Dumitriu is a British artist whose work fuses craft, technology, and bioscience to explore our relationship to the microbial world. She is artist-in-residence on the Modernising Medical Microbiology Project at the University of Oxford and exhibited at venues such as the V&A Museum, London and

The Picasso Museum, Barcelona.

The Picasso Museum, Barcelona.

This sculptural installation explores the complex story of faecal microbiota transplants, used for the treatment of long-term infections caused by the superbug Clostridium difficile. It is not entirely clear how these transplants work but they were approved for use in the UK in March 2014 and have a high success rate in cases where traditional antibiotic treatments have failed. However, the long-term effects are not entirely clear and there are concerns that the composition of our gut bacteria may affect us in untold ways, for example influencing our mood. Faecal transplants performed in hospitals are carefully screened for harmful agents, but there is concern around riskier ‘do it yourself’ transplants which have started become popular, especially in countries where such medical procedures are not available. This enigmatic work comprises a prepared faecal transplant, textiles stained and patterned with gut bacteria, anatomical glass, and an unlocked carved wooden box.

This project explores potential ways in which our harmless bacterial flora could be enhanced to create human superorganisms with better appearances, better health and even better personalities, through active colonisation with hypersymbionts; bacteria that not only happily co-exist on and inside our bodies, but which actively improve us. These “products” contain genuine ‘psychobiotic’ bacteria genetically engineered by the UCL iGEM 2015 team. Their genetically modified E. coli expresses a gene that increases Serotonin production, indicating the possibility of genuinely augmenting our bodies and minds using bacteria to make us happier. Dumitriu worked with Heather-Rose Macklyne to freeze dry the bacteria to make a dust (which was given some added sparkle for cosmetic purposes), which was incorporated into toothpaste, lipstick and food. Dumitriu and Macklyne also made some jellies containing the necessary antibiotics to enable the bacteria to retain the Serotonin producing plasmid. They were grown and decorated with the bacteria.

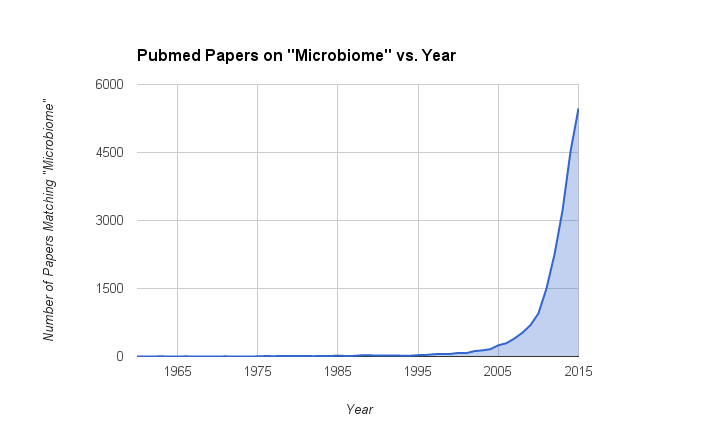

PubMed on the microbiome

|

PubMed, a database maintained by the National Library of Medicine, is a wonderful repository of published biomedical literature. Not only can one search the database to find recent articles on myriad topics, but also one can explore the history of these topics. In this graph, Dr. Jonathan Eisen, a biologist at the University of California, Davis, shows the explosive growth of papers in the PubMed database found using the search term “microbiome.” Between 1956 and 1975, the number of papers in a given years never exceeded three. In 2015, nearly 5500 microbiome-related articles were published. And the numbers certainly will continue to increase.

|

KATHY HIGH

Kathy High is an interdisciplinary artist working in the areas of technology, science and art. She works with animals and living systems, considering the social, political and ethical dilemmas surrounding medicine/bio-science, biotechnology, and interspecies collaborations. High is Professor in the Department of the Arts, at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY.

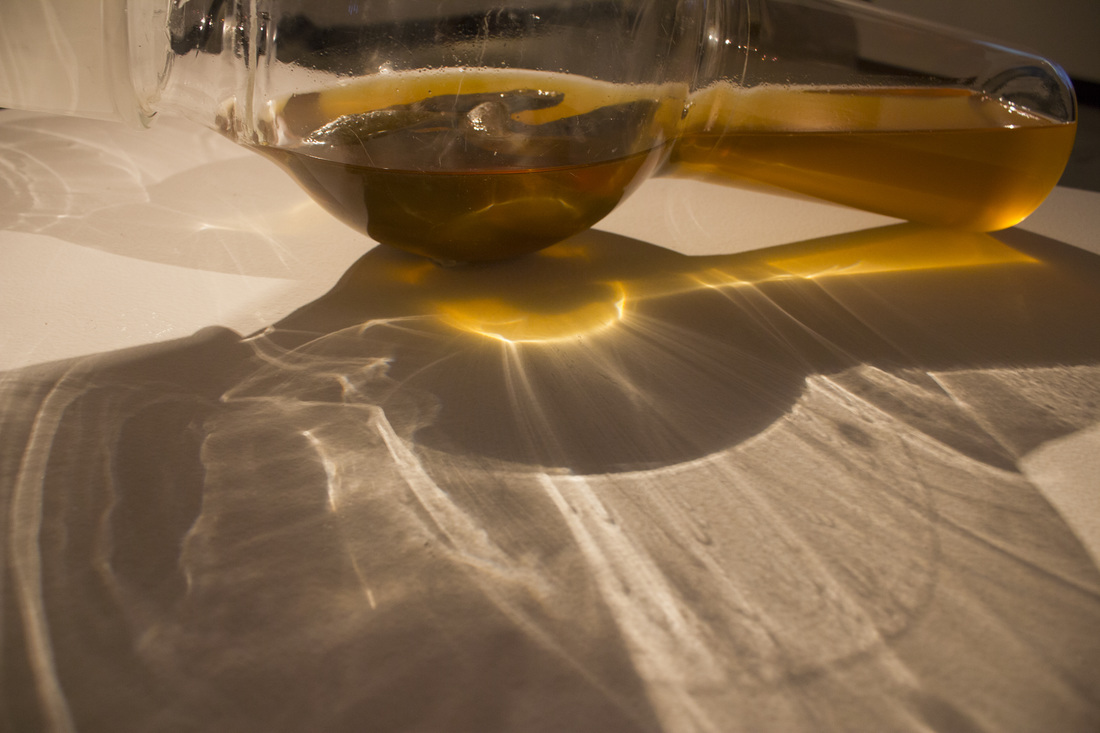

This is a prototype of an at-home, DIY stool bank for the future, using honey as a natural preservative – using its antimicrobial properties. This speculative model is a rounded glass container that can be rotated, and has a glass cap for easy access.

I predict that stool will become a valued commodity in the future. It could be used to heat our houses, to cure a wide array of diseases, and we could find that our guts are in fact our real brain. All this points to the fact that people should preserve “healthy” poop to insure access to it in the future.

“The Bank of Abject Objects” expands ideas around imbalances of internal biomes as a mirror to the imbalances in our larger ecological sphere, where the gut is a “hackable space.” Having dealt with issues around shit all my life, I see my own attempts to make this material invisible reflects our culture’s ways of covering waste. This new visibility will allow for dialog between ecologists, biologists, activists and artists to catalyze the imaginary around the abject. “The transformation of waste is perhaps the oldest pre-occupation of man.” - Patti Smith

The Bank of Abject Objects. DIY stool bank prototype with honey as preservative. Glassware: Bill Jones, Stool samples: Jillian Hirsh, Photos: Mick Lorusso

This series of photos was produced February 2015. I had been doing research about fecal microbial transplantations – the transfer of one person's feces to another person's bowels for curative purposes. A friend asked whose stool I would like to use if I were to have an FMT: “David Bowie’s poop!” I had always been a Bowie fan – but this exchange would be different. I felt as if Bowie’s poop would allow me to join with his gut bacteria, becoming a little bit of him. I created this series of photographs emulating classic Bowie portraits to be offered to Bowie in exchange for his feces donation - so that I might perform a fecal transplant with his stool.

Of course, the exchange never happened. He did not respond. Sadly, Bowie was battling cancer in this last year of his life. Even the day before his death I was plotting with a friend to try to meet his wife, Iman, at her local gym upstate to ask for his stool. But it was not to happen.

The desire was still there. The desire to take in someone else - and take them on. Bowie was the best I could do.

Kathy as Bowie. Proposed Exchange project with David Bowie. Photographer: Eleanor Goldsmith, Make up artist: Jeanna di Paolo

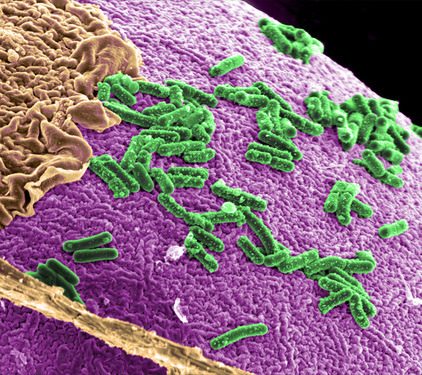

Intestinal bacteria

|

Scientists at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in the U.S. are developing a model of the microbial environment inside the human gut. This model is composed of three-dimensional human intestinal cells cultured with specific gut bacteria. Changes in certain bacterial populations within the gut have been attributed to colon cancer, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases. The three-dimensional model provides an approach to study how changes in bacteria affect gut health and overall human health. Research was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and PNNL’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development initiative in chemical imaging.

Courtesy of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory |

RACHEL MAYERI

Rachel Mayeri is a Los Angeles-based artist working at the intersection of science and art. Her videos, installations, and writing projects explore topics ranging from the history of special effects to the human animal. Her multi-year project Primate Cinema explores representations and subjectivities of human and non-human primates in a series of video experiments. With a major arts grant from the Wellcome Trust, commissioned by the Arts Catalyst, she created Primate Cinema: Apes as Family, a film made for a chimpanzee audience, which also screened at Sundance, Berlinale, and Ars Electronica. She is professor of media studies at Harvey Mudd College.

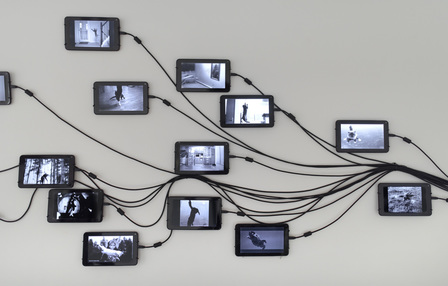

A 29-screen video installation portrays the “Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii” alongside the memetic proliferation of cat videos. T. gondii is a parasite spread by cats, which is present in 30% of the human population. The microbe reproduces in the guts of cat, and is spread fecal-orally. Imbibed by other animals, it produces cysts in muscles, even the eyes and brain. Mice and rats with toxoplasmosis lose their innate fear of cats, and are instead aroused by the smell of their urine, causing a "fatal attraction." The cats can capture and eat these docile rodents, enabling the parasite to complete its life cycle—through mind control. Studies suggest that the parasites may change the behavior of human animals too, making women more gregarious and men more impulsive. The installation explores the relationship between our biological affinity for cats and the technocultural expression of that desire, beginning with one of the earliest films, Marey's "Falling Cat," and recent permutations of the viral cat video.

François-Joseph Lapointe is full professor of biology at Université de Montréal. As a scientist, he is interested in molecular systematics, population genetics and metagenomics. In parallel, he also employs the methods of molecular biology and actual DNA sequences as tools and substrate of artistic creativity. As an artist and researcher in bioart, he applies biotechnology as a means of dance composition, and he has created the field of choreogenetics. For his most recent artistic project, he is currently sequencing his microbiome (and that of his wife) to produce metagenomic self-portraits, or microbiome selfies.

As part of my hybrid work, I play with the fuzzy boundaries between art and science, research and creation, and the fear and fascination that people have with germs, viruses and bacteria. In my practice, I use my body as a laboratory, and I monitor the transformation of my personal microbiome in various experimental conditions. The data collected during my performances are then used to generate portraits of my microbial self, or microbiome selfies. These self-portraits are depicted as microbiome networks, not unlike those published in the scientific literature, to illustrate the intricate relationship we have with the microbes living on us, in us, and around us.

Work # 1 Microbiome Triptych

Microbiome selfie constructed from samples of my gut and oral microbiome collected after eating a burger. The three panels present different visualizations of the same network of bacterial DNA sequences, showing the nodes, the links, or the nodes and links at once. The different colors represent distinct microbiome samples.

Work # 2 Becoming Batman

Microbiome selfie constructed from samples of my oral microbiome before AND after eating a fruit bat in Guinea, right in the middle of the Ebola outbreak. The colors of this network of bacterial DNA sequences represent different microbial communities.

Work # 2 Becoming Batman

Microbiome selfie constructed from samples of my oral microbiome before AND after eating a fruit bat in Guinea, right in the middle of the Ebola outbreak. The colors of this network of bacterial DNA sequences represent different microbial communities.

Belly Button Diversity

|

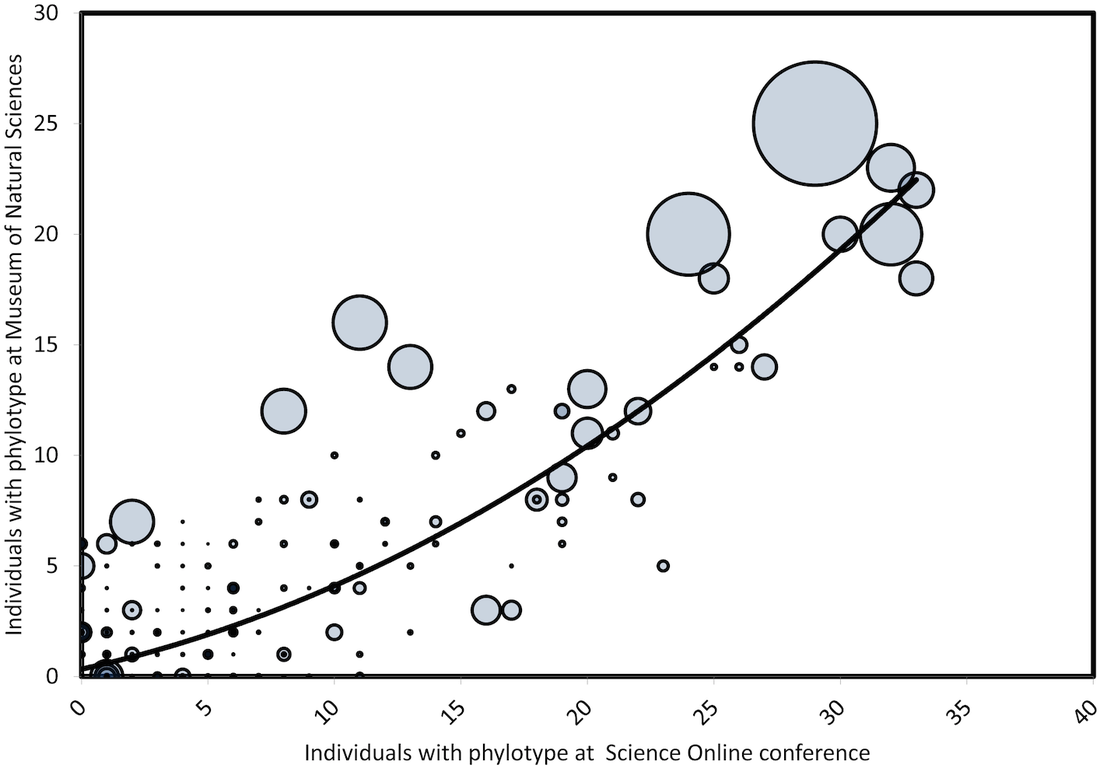

We know that billions and billions, perhaps trillions, of microbes live on us and in us. How similar, or dissimilar, are the bacteria on two different people? To address this question, a group of researchers used a citizen science approach to investigate the microbial diversity of a very specific habitat – the human belly button. Volunteers used a sterile swab to collect microbes from their belly buttons. The researchers then analyzed them. Not surprisingly, they found that a great deal of diversity exists. However, similar types of bacteria were seen in different groups of volunteers. In this figure, the researchers compare the belly button bacterial diversity found in visitors to the Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, North Carolina and attendees of science communication meeting. Each dot represents a type of bacterium. The size of the dot indicates how often that type of bacterium was observed. The most common types of bacteria in the belly buttons of visitors to the museum also were the most common types of bacteria in the belly buttons of conference attendees.

|

MEHMET CANDAS

Mehmet Candas is a scientist, educator, and occasional multimedia artist at The University of Texas at Dallas. He teaches Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Biotechnology, Cellular Microbiology, Modern Biology, and Human Body Systems in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

His research interests concern questions on biochemical and genetic basis of cellular responses to environment and how cells integrate signals

into survival or death pathways.

His research interests concern questions on biochemical and genetic basis of cellular responses to environment and how cells integrate signals

into survival or death pathways.

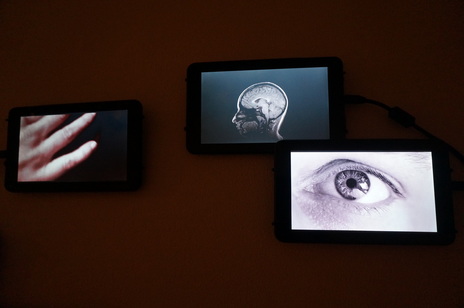

Symbiotic Unconscious is a digital animated collage generated as a soundless imaginative rendition. The work was created with combinations of images animated and arranged in transitions on a digital presentation file. It entertains the concepts involving the relationship between the human body and gut microbiota, and how the complex nature of gut ecosystem influences physiology and brain activity. It emphasizes the fundamental notion that life on Earth originated as prokaryotic cells. These single cell microorganisms evolved with amazing diversity and dominated the biosphere nearly 3 billion years before the first eukaryotic cells descended through cooperative union of some prokaryotic cells. Arrival of eukaryotic cells ushered in a whole new era for life on Earth, giving rise to multicellular life forms, including all plants and animals, on the evolutionary scene. Long history of coexistence of microorganisms with plants and animals shaped symbiotic relationships with ecological and environmental significance. These evolutionary associations formed metaorganisms consisting of multicellular hosts and communities of associated microorganisms. Like all animals, we humans are colonized by microbial communities, which collectively are called microbiota. These resident microbes outnumber our own cells. Vast majority of our microbiota is associated within our gastrointestinal tract, or gut. The gut microbiome - the composition of gut microbiota along with their genes and metabolic products - has enormous impact on our physiology, both in health and in disease states. The effects of gut microbiome on our body involve diet and environmental variables as well as hereditary factors. Gut microbiome also influences our behavioral responses through bidirectional communication between central nervous system and enteric nervous system, which is recognized as the brain-gut axis. Dysbiosis, or disturbed microbiota, and alterations in bidirectional brain-gut microbiota interactions are linked to inflammatory pathology, gastrointestinal diseases and metabolic disorders as well as neurodegenerative and psychiatric neurological conditions. These findings now prompt us to reevaluate many concepts in medicine and brain sciences. Translating how symbiotic interactions involving gut microbiome act as an unconscious system and influence human body and mind certainly will play an important role in advancing knowledge on health, disease, brain functioning and social interaction.

Anorexia

|

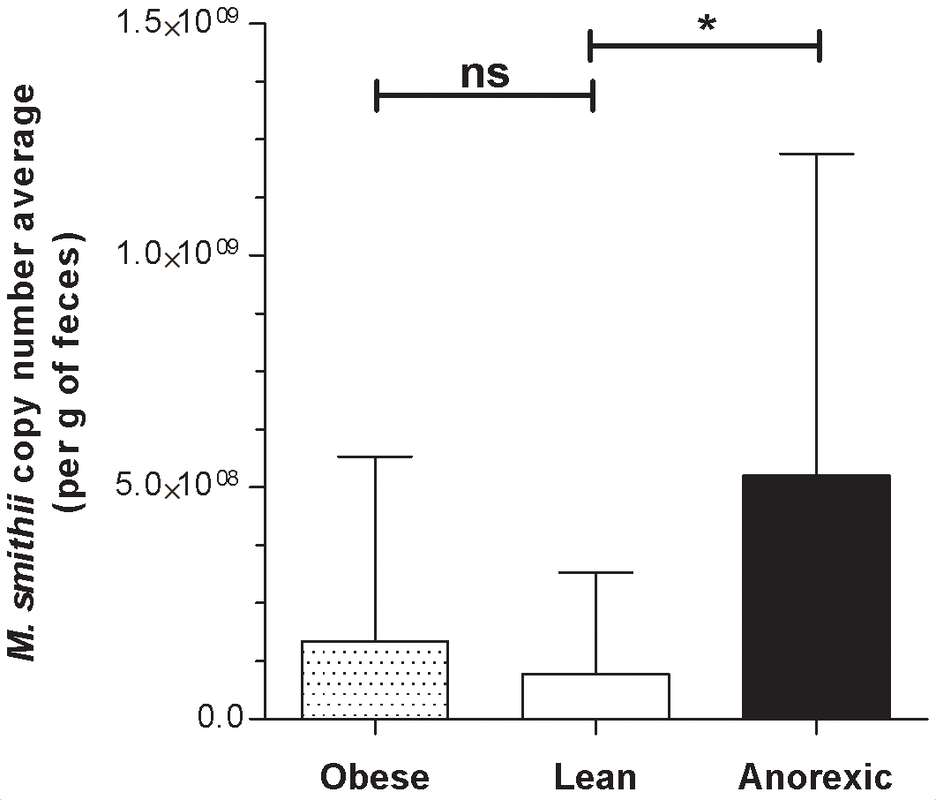

How does our microbiome affect our health? Every day, we are learning more and more about the intricate, essential relationship between us and our microbiome. In one study published in 2009, researchers examined the types of specific microbes in the gut of individuals who were obese, lean, or anorexic. As shown in this graph, they observed significantly more Methanobrevibacter smithii, an archaeon, in the feces of anorexic individuals than in the feces of obese or lean individuals. How can we explain this difference? Previous studies showed that mice experimentally colonized with M. smithii gained more weight than mice devoid of this microbe. Perhaps, the increased amount of M. smithii in people with anorexia is an adaptation, helping the body extract more calories when subjected to a limited amount of food.

Armougom F, Henry M, Vialettes B, Raccah D, Raoult D (2009) Monitoring Bacterial Community of Human Gut Microbiota Reveals an Increase in Lactobacillus in Obese Patients and Methanogens in Anorexic Patients. PLoS ONE 4(9): e7125. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007125 |

MEREDITH TROMBLE

Meredith Tromble is an intermedia artist who often works collaboratively with researchers. Her installations and performances have been presented internationally in venues ranging from the Mills Museum to the Glasgow School of Art. Since 2011, she has been artist-in-residence at the Complexity Sciences Center at the University of California, Davis.

As I made Mr. Science and the Microbes, I was thinking about the dream of eradicating “germs.” Although Mr. Science’s “arms” are made with cleaning implements, the boundaries of his person seem to be breaking up. Despite his protective glasses, a rather large microbe is exploring his forehead. His bottom half, his “foundation,” has deflated. Where his feet might have been, tarry stromatolites are emitting more microbes. Although he lives in a space that someone has tried to rationalize with white paint and a black framing line, everything is dirty and the microbes seem to be having a much better time than he is. How will he come to terms with them? Mr. Science is not a real scientist, but a personification of a certain scientific authority in everyday culture. He’s not going to make it in a world in which we know that we have microbial ancestors, microbial innards, and an “I” that emerges from conglomerations of millions of very, very small beings. We will have to hang on to our sense of humor and welcome a new way of understanding ourselves.

Mr. Science and the Microbes, 2016. Mixed-media installation, dimensions variable

The Fear of Microbes series is an offshoot of the installation Mr. Science and the Microbes. That installation is humorous, ironic, even a bit befuddled; these images revealed a serious undertone. A ghostly face appeared from the cell membrane and organelles of one of the “microbes” in the first photograph. In the second photograph the microbes leave their floating world to crawling up the window sill into human space; the third photograph shows the cleaner that might be used to control them immobilized by red bonds.

Fear of Microbes, 2016. Series of three digital prints, each 20 1/4” x 15'

Origins of our microbiome

|

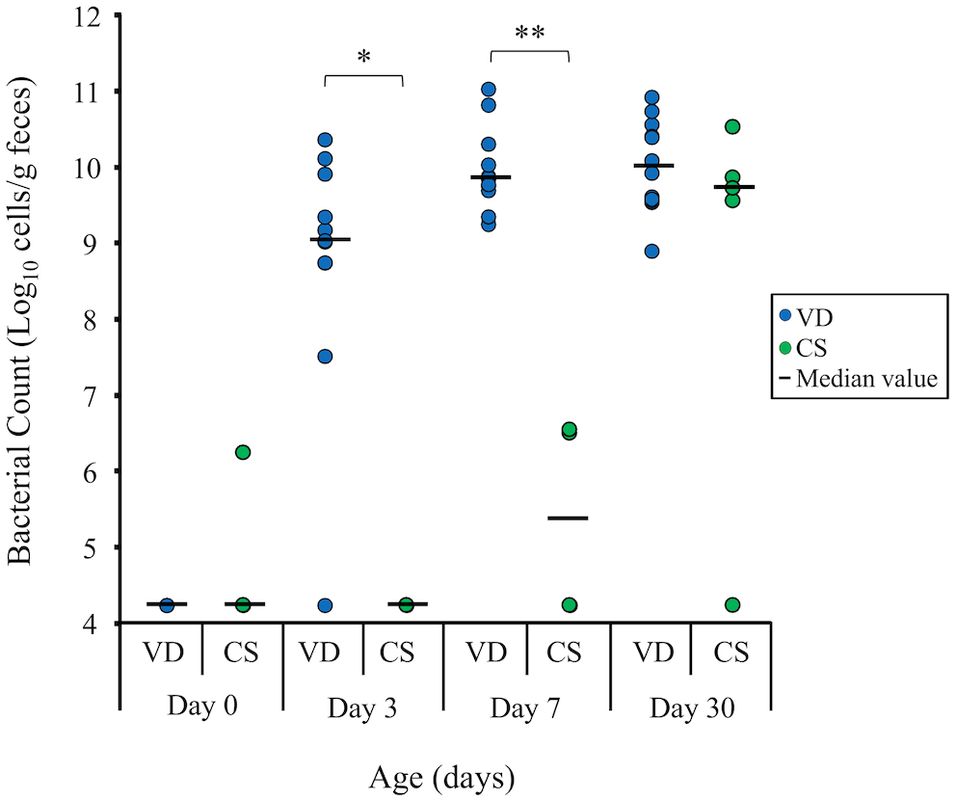

How do we acquire our microbiome? As we learn more about how our microbiome affects our health, we also are learning more about how we acquire our microbiome and how it changes over time. In this study, researchers examined the effect of vaginal delivery versus C-section on the acquisition of bacteria by infants. At various times post-delivery, researchers determined the amount of a difidobacteria in the feces of new-born infants. At day 3 and day 7, significantly more of these bacteria were present in the feces of infants born via a vaginal delivery. The effects of this difference, if any, aren’t known. But, quite clearly, the mode of delivery affects the acquisition of microbes by the infant.

Makino H, Kushiro A, Ishikawa E, Kubota H, Gawad A, Sakai T, et al. (2013) Mother-to-Infant Transmission of Intestinal Bifidobacterial Strains Has an Impact on the Early Development of Vaginally Delivered Infant's Microbiota. PLoS ONE 8(11): e78331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078331 |

ADAM ZARETSKY

Adam Zaretsky, Ph.D. is a Wet-Lab Art Practitioner mixing Ecology, Biotechnology, Non-human Relations, Body Performance and Gastronomy. Zaretsky stages lively, hands-on bioart production labs. He also runs a public life arts school: VASTAL (The Vivoarts School for Transgenic Aesthetics Ltd.) VASTAL was opened as both an artistic gesture and in order to make hands-on biotechnology labs more accessible to the public. During the following years, VASTAL has publically held living-art performance labs with accompanying Unstill Life Studies (ULS) lectures.

“The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) is based on studying the life that lives within us. This is our second genome, our internal ancestors and possibly the source of our third mind. What kind of beings might result after insertion of scrambled genes in their family tree? What kinds of identity splay can we expect from becoming bacterial? In which ways will this project change the cultural reception of scatological action?”

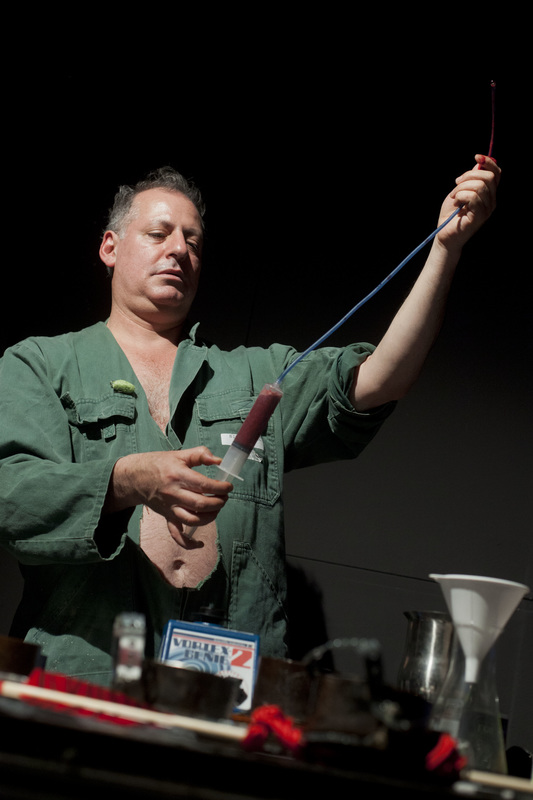

In mutaFelch- a DIY (Do It Yourself) biolistic genegun is used to bombard a mixture of human sperm, blood and shit with raw hybrid DNA soaked in gold nanocarriers.

mutaFelch- Methods of Transgenesis: Genegun (Biolistics), performed at: Queer New York International Arts Festival and Grace Exhibition Space

and Kapelica Gallery

and Kapelica Gallery

Photos: Miha Fras / Kapelica