|

Devika My experience with the Bridge Residency has been inspiring, and it was such a pleasure to work with Michael over these past few months. Our shared love for neuroscience and dance drove many of our discussion topics, which ranged from brain shift to spinning hydrogen protons to better understanding the motor symptoms underlying Parkinson’s Disease, and I look forward to continuing these conversations in the future as we both carry on with our respective “Sci-Dance” endeavors! On a more personal note, I’ve chosen to shift the topic of my physics-inspired dance piece away from brain tumors due to recent events in my life. A few weeks ago, I began to experience severe migraines, which began to impact my vision in my left visual field. One day the pain was so excruciating that I was taken to the emergency room and underwent a series of neuroimaging tests (i.e., EEG, CT, MRI). I am in recovery now, but while I was in the hospital, I had the opportunity to learn what it was like to be the patient. A challenge I’ve expressed previously while working on the narrative was capturing the emotional aspects of undergoing these tests - as usually, I’m on the other side the scanner and can only imagine what is going on from the patient’s perspective. The universe works in mysterious ways, and I’m taking this as a learning experience to share my story. Michael

I found the process of joining forces with a scientist to be enlightening and inspiring. It was extra exciting that my team member had studied classical Indian dance for so long. And I am glad to see that she made such a great link between her current work as an MRI technician with choreographic elements involved in that type of dance. I am also interested in seeing her dance develop as depicted elements of the MRI process, and certain molecules affected by the machine in that process. I think it’s a unique perspective and one worth depicting for an audience. We had some stellar conversations shooting ideas back and forth, posing some great in-depth questions to each other, helping each other dig deeper, and find exactly what we are looking to accomplish along the way. I feel like we made a good team, as a sounding board for each other, and support system from afar. And I hope to be more involved as her dance piece comes to life, in process to full fruition. Dramaturgically speaking, I enjoyed offering my insight into theatre making, and I enjoyed hearing of her concepts coming together through conversation. I loved offering solutions or ideas as much as I could. That being said, we were enjoying our respective work so much that although we had an interest in working together on a performance piece about cancer, I think we kept that on the back burner for something in the future. For the piece I conceived with writers from The Brooklyn Parkinson Group I’ve pinpointed the scenes that would benefit from more scientific facts as an underscore to the emotional narrative. We had a reading on Friday, December 21st to a good reception with great feedback. One of the notes received being about how the piece really hits home for people. They see themselves. They see people they know. And I believe with an underscoring of real science, the audience might even be moved themselves to feel what it’s like to have Parkinson’s. From the distinct MRI, CT or other medical tests involved with certain injuries, to the exercises that the neurologist and Physical Therapist do in practice, all of these should be technically sound and realistic to ensure a greater understanding from an audience with no Parkinson’s experience, and greater acceptance by those with Parkinson’s experience. There are other immersive elements I’m not at liberty to discuss publicly, because it’s something unseen in theater as of yet, but it will make for an exciting and engaging presentation for audience and actors alike! There is much more work to do, as we begin to put the show on its feet. Some further exploration in the physical symptoms or manifestations of Parkinson's will be highlighted in a big group dance number, symptoms like bradykinesia, dyskinesia, festination, visual disturbances, sleep disorders, and even hallucinations. Certain unseen symptoms like depression, loneliness, apathy, and emotional disturbances will be depicted as well, through dance or in the spoken word, during book scenes. I look forward to delving deeper into the creation of this performance piece. And I look forward to gathering stories from cancer patients and survivors, oncology professionals as well. If there’s another disease that is more prevalent than neurodegenerative conditions I believe it’s cancer, and I would be honored to collect stories or art to make a documentary style theatre piece to depict not only the biological conditions within that molecular war, but also the war waged upon families both during and after such events. Both stories are steeped in drama and conflict, and hopefully ripe with insight and humor too. Please follow along in my adventures through my website michaelvitaly.com. Or if you’re more of a wordsmith, my Twitter is a fun place to keep up to date in my scientific interests and artistic endeavors. If you’re an image driven storyteller through my Instagram: @RealityandTruth (under the alias Jack Burden, named after a character in All The King's Men, a favorite book of mine). If you have a connection to Parkinson’s or just want to chat dance theatre and the like, don’t hesitate, I’m reachable through these channels, or my site.

0 Comments

Devika

Music is comprised of individual notes, and transitions between these notes can often seem either effortless or demanding. Naturally, many of us would prefer the smooth transition from one note to the next, but perhaps it is when we surrender to the uncertainty of what is to come next do we realize that we’re actually working towards something spectacular. In the same vein, creativity in dance, as well as in science, occur in these moments of uncertainty. More specifically, I’ve come to realize that it takes place in moments of near stillness. In the current dance piece I’m learning, a thillana, the second thematic line is considerably less physically-demanding than the first - where my arms and legs are racing to match its speed of the complex rhythmic beats. On the other hand, while the second thematic line would still be considered fast, only my eyes are traveling across an imaginary horizontal plane of transversal magnetization during this part, and my almost stationary body is like a longitudinal magnetization - characterized by subtle fluctuations of my shuffling feet as I try to maintain my balance. A similar thematic line where the dancer must be still and can only move their eyes also exists as the second phrase in another piece I learned earlier last year, which was a jatiswaram. The same choreographer composed both pieces, so this decision to incorporate moments of near stillness is deliberate - but why there? Is there an associated significance? It’s possible that yielding to this uncertainty is therapeutic, as it partially restores the energy you exerted from dancing the first thematic line, as well as having you devote attention to your surroundings and prepare for what is to come - much like a precessing proton of a water molecule in the neural tissue of patient undergoing a MRI scan, where the moments in between sequences both allow the proton to realign its orientation to its natural state and while still knowing that it will again have to change its position when the next sequence begins. I hope to address these aspects of movement and more in the current physics-inspired dance piece that I’m composing. To follow along, my website is www.devikanair.me and on Twitter, my handle is @nairdevikav. (Below is a picture of me in classical dance attire after performing the same jatiswaram early last year.) Devika For a performance art, like dance, music is an integral component to the piece - sometimes more so than the dancer’s movements. Individually, movements carry little, if any, meaning if not accompanied by the right music, because from the audience’s perspective, music, or sound, is often what first captures our attention. A few days ago, I was perusing through Free Music Archive, a fantastic open-source platform to share and discover new music, and serendipitously came across this beautiful instrumental recording by a renowned, partially blind violinist (Professor Dwaram Venkataswamy Naidu) from southern India. What struck me the most about this piece was its deceptive simplicity, a phrase many have used to describe Dr. Naidu’s artistry. Recorded around the 1940s, there is an element of rich disorderliness, or melodic fuzziness, to this piece that is rather challenging to describe with words. The initial few seconds begin with that familiar crackling sound before merging with the melodies of the violin. The air is still, but as soon as the violin starts playing, the water molecule enters the scene and travels randomly around the room by spinning and colliding with other water particles - an attempt to represent Brownian motion in a biological environment. There’s an element of familiarity in this movement, because this is its natural state. That is, this is how water molecules move in its local chemical environment in the body. This familiarity then develops into a sense of optimism near the 40 second-mark, but around 1:15, the cadence rises and there is panic, or rather a change to the local chemical environment. This alteration is representative of the shift from a healthy cell to a cancerous one. The dancing water particle is still spinning and interacting with nearby particles, but movements are slower and more deliberate, and is conscious of this change a little before 1:38, which is indicated by a series of noticeably rapid rhythmic beats. Following this, there is acceptance (around 1:52) and the particle is fighting for its survival. Then the tone changes near 2:30 where the particle has to make a decision. I have yet to think of a conclusion, but hope to have it finalized in the coming weeks. What is constant, though, throughout this recording is that element of rich disorderliness (or melodic fuzziness), which quickly settles into the background. But, does this fuzziness exist to mask the subtle “inaccuracies” of a piece of music that was recorded roughly 80 years ago, and why do we so often equate disorder with imperfection? Maybe it is these imperfections that help us better understand that part of ourselves and our natural world that we so desperately try to make sense of. Michael

It seems to me the human story behind artistic representations of brain processes would make for a more engaging topic then simply seeing beautiful structures or formations on stage. That is to say, I believe the power of theatre rests on the insight an audience gains from landing within the world of the character so fully that they can start to see similarities between the character and themselves. On stage, when someone of differing backgrounds or class, culture or circumstance butts up against something challenging or existentially awakening, it can sometimes elucidate an empathetic understanding, especially for an audience who is able and willing to make such connections. In plays, as in other literary examples there are rising actions, inciting incidents, climaxes, and perhaps emotional peaks and valleys; and even when we find a character at some juncture very unique to them, even if it might seem there are no similarities or parallels one can draw, I believe it is then the spirit of the experience that might capture the spirit of an audience, if not the detailed letter in exact measure. In essence, I think bigger themes can emerge from the nitty-gritty in the details, and sometimes the little things can be the biggest of things. What then can we show as we decide to depict cancer on stage? From the microscopic level of cellular division and defenses against necrosis and the like, to the emotional underpinnings of what a person and their closest network might go through in the fight, how do we navigate both worlds of the micro and the macro? How much do we show of a person’s story in order to get to the scientific facts? Is it necessary to know everything about a person in order to be moved by their experience? Or can we see simple semblances of relationships, snippets of moments, and momentary glimpses or slices of life, snapshots to get the gist. And in that case, are we cheapening the human experience in order to explore the scientific? I suppose there are narrative elements that will shine through when defining something as complex and all-encompassing as cancer. In exploring some of these questions, I suppose we can see the power of storytelling. As we shift our attention to someone else’s story, perhaps, in turn, we may end up seeing our own from a different perspective. Doesn’t great literature bring to light some of humanity’s complexities in various shades and colors, with either subtle beauty or grotesque depth? I think on dueling figures (of opposing forces/viewpoints), characteristics we all might have within us, if we are willing and able to accept it. Characters likes of Count Vronsky or Levin in Anna Karenina; or Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson. By seeing both types of people depicted, richly drawn too, and how they deal with challenges, I think we can connect to our own story, our own way of dealing with challenges. It’s not often we get to connect with our story in a new way, but I believe in a live theater setting, where the action takes place moment to moment, right in front of you, an audience might be able to more easily draw parallels to their own life, by simply receiving the story as it unfolds. The added step of reading and cognitively ingesting the story might make for a longer route to one’s own psyche, but I’m just speculating. And of course, this is all assuming your audience is blessed not only with all 5 senses, but also an open enough heart to let someone’s story in, in the first place. That being said, making theater an inclusive enough space for members of your audience who might be deaf, or blind, or perhaps on the spectrum, can be challenging, but it’s not impossible. I have been in productions that have attempted to make shows accessible to these three populations, and I have also tried to produce shows with added efforts in advancing modes of communication to help reach as many people as possible. Making theater in an immersive way is another way to help audience members experience the story in a palpable or visceral way. By either diminishing or aggrandizing certain sensory elements, by selectively curating what an audience sees, hears, or senses, you can essentially put everyone in the same space, on the same page, and closer to your character’s experience, and their story as well. From our conversation last week, Devika has helped me understand the efforts of some unsung heroes in the medical community: the MRI technicians who actually handle the day to day volume of people coming in to get MRIs. All day long they help administer some of the most important, and also sometimes the only measure of how cancer moves in the body. Either for routine checks, follow-ups, or first procedures people dealing with an onslaught of emotions come in and out of centers around the world, it is the technicians who take them by the proverbial and sometimes literal hand from the unknown to the crystalline. Knowing full well the importance of their work, and the importance of clarity in their images, they have seen the very smallest of us fight innately against something that only knows how to reproduce and feed off of what it sees. There is something deeply compelling there, in that fight, and not altogether non-human as I first thought, but something actually deeply human. The things our brain cells and tissues go through when facing cancer cells seems inherently dramatic now, and also full of conflict too, something that is deeply woven into the fabric of all storytelling. Devika

What determines the frequency of processing protons? Its local chemical environment, and in this story, we are going to witness a battle between aggressive tumor cells infiltrating normal cells. These two cell states represent a two distinct environments. To demonstrate this change on stage, I’ve considered the following:

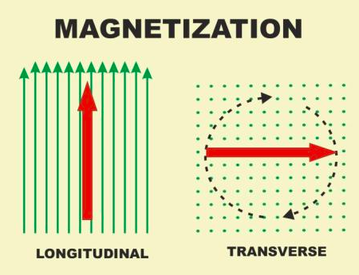

In regard to music, the highly rhythmic vibrations from the mridangam (an Indian percussion instrument) will accompany the dancing proton residing in the normal cell, while slower rhythmic beats will be paired with the proton processing in the cancer cell. To dramatize this effect, I may bring in a violin. For context, there are several key metabolites (or small molecules within brain tissue, and each metabolite has its own unique frequency that is sensitive to its immediate environment. Hence, protons belonging to different molecules will have a slightly different resonance frequency - due to individual differences in their typical chemical environment. And, if a change to this frequency is observed, that can be indicative of disease. Thus, when you put a person in a MRI machine you can learn about the composition of the patient’s neural tissues through specified mechanisms. One of these mechanisms involves knowing that the MR signal is reflective of the number of spinning protons, so tissues with a greater number of protons will have a higher signal. So, what does this say about the signal of cancer tissues versus that of normal tissues? Devika As I started drafting my narrative this week, I mind kept drifting to last week’s dance class. We had just begun learning a new thillana, a highly rhythmic classical piece that demands precise timing and synchronization. What’s fascinating about these kinds of pieces is that they demand a level of stamina where we live in between moments of control and abandon. Driven to better understand this “in between” state in physics, I delved a bit more into the role of radio frequency pulses, which are short bursts of energy sent to disturb the precessing protons, once the patient is in the scanner. Yet, only certain radio frequency pulses excite, or rather perturb, the alignment of the protons - that is, there needs to be an exchange of energy between the pulse and the proton(s) of interest. It’s the difference between exchanging glances with someone and pushing someone to the point where they lose their balance. In the latter case, your alignment would be disturbed. However, for any energy exchange to occur, the pulse and the precessing protons must have the same frequency. When this happens, some of these protons are taken to a higher energy level (facing down, as opposed to facing up), and now, the longitudinal magnetization along the z-axis decreases. So, in my piece, I would have one arm of the dancer represent the longitudinal magnetization (z-axis), while the other representing the transversal magnetization (x-y axis) in their invisible Cartesian coordinate system - and to show that there are multiple protons, I may have the dancer change the positioning of their arms.

Devika Currently, I have a small collection of moments, but nothing cohesive to the point of an established narrative. I want to share an experience of a person going into the scanner for the first time via classical dance (with some theatrical elements). This week, I spent time formulating my story’s direction and defining the various parallel experiences I’d like to incorporate:

For inspiration, I revisited one of my favorite memoirs, When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who learns that that he’s diagnosed with a terminal form of lung cancer. What I admire most about his storytelling is his ability to navigate critical transitional moments, like exchanging his doctor’s coat for a patient gown. There’s a sudden change in his local environment and the rate at which he now has to live his life has altered. Like Dr. Kalanithi, delving into these transient moments and trying to make sense of the unfamiliar is the how I want to share my story. Ultimately, I want the audience to walk away from this having better understanding of ourselves and how the world works - to know a little bit more and to reach beyond those who usually engage. Michael

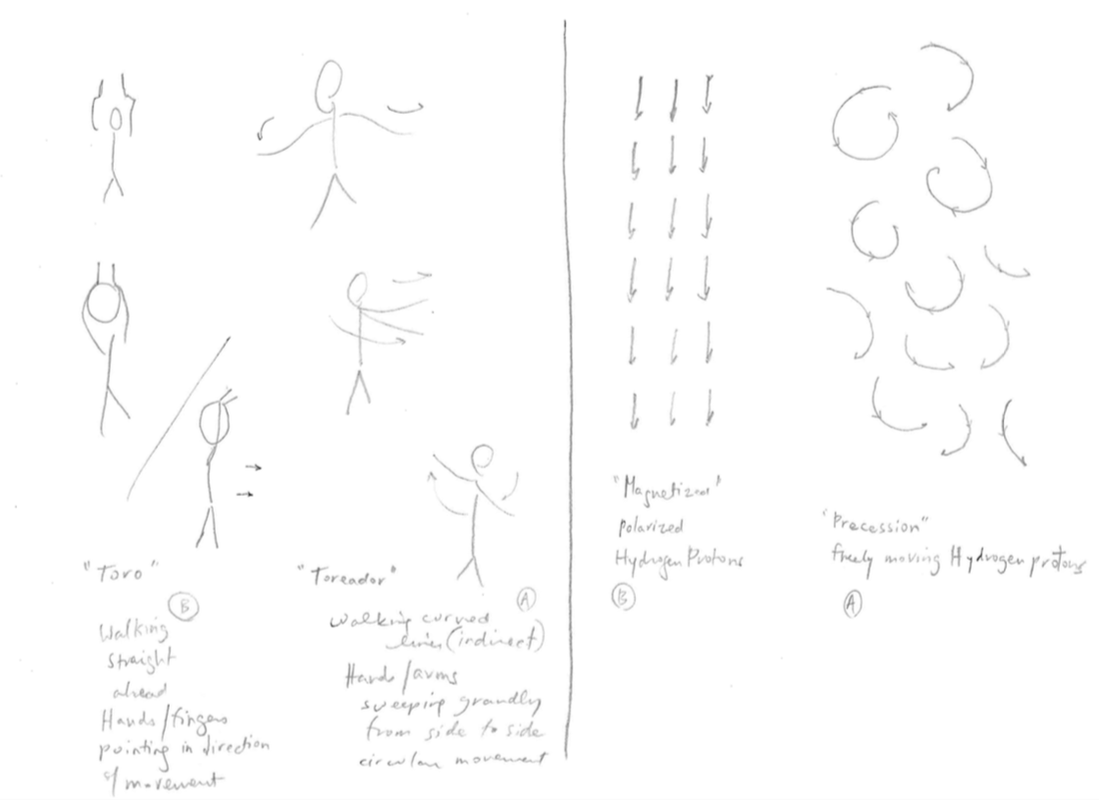

While building the exercises for PD Movement Lab last week, I thought about how best to distill the movement I wanted to create into easy to process images and words. I wanted to make something replicable and easy to memorize, partly improvised, and able to be portrayed by unique bodies with a myriad of movement abilities. On top of that, I wanted to portray two very distinct qualities. In order to inspire the most accessible movement worlds between hydrogen protons before, during, and after the magnetization phases in an MRI machine, I focused on direct and indirect movement, as well as emotional states of being displaying similar aesthetics. As we warmed up in the chairs I made sure to accentuate our efforts towards visual focus. I found it a great tool to establish both a sense of fluidity and freedom, as well as a fiercely focused effort. Adding to our visual focus we also played with direct and indirect emotional physicalizations. Utilizing stock characters from commedia dell’arte, the essences of the Lovers versus Pantalone were tapped into. Physical elements from the first stock character I chose, the Lovers, revolved around being light and airy, chest lifted, arms out, eyes foggy, and hearts fiercely focused towards their partners. The second stock character was contracted while their arms were lower at their sides, fingers grasping and clutching. To build a mind body connection, I added the voice with repetitive lines like, “I love you, I love you, I love you!” and “Gimme, gimme, gimme, gimme!” I described each of their points on the status level within the structure of drama back then, but relied heavily on the essence of each character for improvisational play. I was able to engender distinct modes of emotional grandeur between participants, with relatively ease. I built off of these effort qualities when I moved into standing and moving across the floor, when I created the two movement worlds from another pair of conflicting characters: the toro and the toreador (or the bull and the bull fighter). One exudes a grandness and haughty nature complete with swirling flourishes, while the other is a display of brute force and direct unstoppable energy and focus. The physical essence of the toreador can be seen with a lifted chin and chest, within a spiraling torso, exposing and hiding his heart while sweeping his grand (imagined) cape from side to side. The toro itself casts his gaze downward while directly focused on the red cape, and while there was some side to side movement while transferring weight from foot to foot, the main point of focus was the forward direction of his horns, portrayed by raised fingers of course! Our musician, Andreas Brade, played percussion and piano throughout, settling into a nice musical quality, carrying within it a driving baseline while adding arpeggiated lines in the right hand. It was a great time shifting in between both modes, and I called out during the transitions, whether or not some magnetized feelings were longer lasting than others. Overall I found it to be a great exploration with these themes and I was happy with how it turned out. I’ve included some sketches I drew after class… Devika In the previous week, I explored ways of weaving immersive experiences in the context of MRI machines, but for those patients with an operable tumor, there is another facet to their story: the surgery. As a general rule, an operable tumor can be surgically removed with minimal risk. That is, it is neither located deep within the brain (i.e., the brain stem), nor is it near a sensitive region of the brain that regulates vital functions (i.e., movement). When considering movement on stage, a dancer jumps into the air, but is brought back to the floor thanks to gravity. In relation to physics, the force that is applied to floor is an action, while the reaction to that force is a sound. Similarly, during intra-operative motor mapping, the surgeon will electrically stimulate discrete cortical or subcortical pathways of the brain that control movement. As this step is performed prior to removing the tumor, their hope is that mapping these stimulation sites will help guide the resection more efficiently and accurately, as tumors with poorly defined borders may often be mixed with healthy tissue. Thus, in this case, the action is the electric stimulation and the reaction is involuntary movement of the arm or leg. Yet, there is more to the physics of dance than merely gravity and applying forces. It’s important to also consider displacement, a term used to describe an object’s overall change in position. In dance, displacement is the distance traveled by the dancer. So, when a surgeon simulates a pathway, the direction or degree to which an arm will elevate, for instance, is going to vary and there are a multitude of patient-specific reasons of why this is the case. Perhaps the patient is older and has restricted arm movement, and so, the displacement is short. So then, how would you demonstrate this on a stage? You would need to also consider the complex interplay of additional factors, like time, speed, and equilibrium. As expected, each dancer will create a space for themselves, but the distance traveled will inevitably vary. Michael

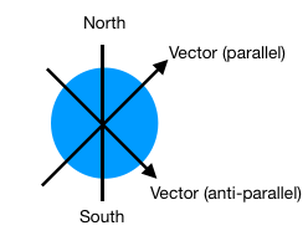

I’m inspired to work with the PD Movement Lab (“Lab”) class this Friday, which differs from Dance for PD a bit in that it was designed to directly address Parkinsonian symptoms with artistic adaptations, while utilizing games or props, physical cueing, and imagery driven lessons to help design new approaches in dealing with some of the everyday of challenges that persons with Parkinson’s might face. The exercises that I’m going to set for class will ideally achieve two sets of goals: making an interesting stage picture by telling the narrative of hydrogen protons during magnetization, and help our Lab participants achieve good locomotive strategies at the same time. To that effect, it will address the work it takes to initiate movements, as well as multitasking, and changing between two distinct movement qualities in sometimes surprising or improvisatory ways. Strategies like “pre-planning,” or as the creator of the Lab, Pamela Quinn has mentioned in some of her writing on “Freezing,” taking an indirect route, might help alleviate the stress to get someplace quickly, by tricking the brain away from the stressful task at hand, and letting it refocus on the body for that initiating moment to go another way rather than going straight for the goal/point of focus. This exercise will also help me understand and depict the science behind MRIs, a conversation that has been of interest to my SciArt partner Devika and I. I have come to realize that during the magnetization process, hydrogen protons go through quite a lot! From their natural states of random movement or what we could even call chaotic freedom, to their magnetized states of paralleled focus and rigidity, hydrogen protons will align themselves or misalign themselves according to the processes of the MRI. Taking these shifting points of extreme states into account, we can give dancers in the Lab concrete cues to work with, like movement that is free, fluid, smooth, curved, flowing; and we can give another set of cues for movements that are more rigid, sharp, angular, focused, linear, choppy. Adding focus and directional alignment to the latter physicality will especially high-light our concept of “magnetized,” having them align themselves directly towards specific points in the room. Embodying these characteristics onstage would take place along the horizontal plane. And through the frontal, or coronal, plane. For fun, and an added challenge, other elements can be added to this, like differing emotional states that might coincide or conflict with the movement style. During the introductory warms up in class I plan on engaging in certain clown based warm ups to enliven the imagination, emotional intellect, and a sense of playfulness. Finding the transitions in between these moments is of great mutual interest to us as well, and I intend to have my class play with the back and forth as well finding ways to go deeply into a proton’s natural state, making sure to create distinct movement worlds of differing states of being. Devika mentioned that perhaps after a long bout of magnetization, we as the hydrogen protons would need time to effectively get back on track, their own track, after being driven by such a rigid and forced energy. Devika When we say protons exert a force, I imagine them as vectors (or little arrows) oriented in a specific direction. They maintain this orientation while precessing either parallel, or anti-parallel, to the magnetic field. To demonstrate this idea, below is basic schematic with two protons positioned in different directions. The vertical line in the center represents the external magnetic field. Yet, protons move, or rather precess, and so, what we see now is just a specific moment in time. If you wait a second, the protons may be in a different position because of this movement (the speed of which will vary depending on the magnetic field). Like a camera, the MRI machine is designed to take detailed pictures inside of your body, and to ensure full coverage of the brain, we need to maximize the number of slices. Slice thickness plays a role here, but standard pre-operative protocols call for hundreds of slices. To portray this in dance, I would need to manipulate light. In between moments of darkness, each dancer would “precess” their way to a new pose - each one different from the last. For simplicity, I may use certain poses, and here are a few that have inspired me. I may have the “standing” positions represent protons at higher energy levels, while “sitting” positions representing protons at lower energy levels - because sitting demands less energy than standing. However, not all “sitting” positions are the same - some may be a bit more difficult, but not as energy-consuming as the standing ones! Demonstrating parallel and anti-parallel orientations is a bit more complicated, and while I mentioned having the dancers not face each other in my previous post, I am now thinking of using specific hand gestures (mudras) instead to convey these two positions. The act of precession (that is, the act of spinning) would be constant, but the degree to, or the intensity, with which they spin will vary among the dancers - as this will depend on which axis of the Cartesian coordinate system they are spinning on and how many protons (or dancers) are present on each axis. Still, while opposing magnetic forces of protons in the x and y axes cancel each other out, individual magnetic forces (or vectors) in the z-axis do not! Rather, these foces will team up and generate a magentic vector in the same direction of the external magentic field. In the coming weeks, I hope to expore ways of depicting this phenomenon, which will be both interesting and challenging, because in a way, it’s as if the person has their own magnetic field. Michael

This entry is dedicated to the inimitable and ever inspiring Leonore Gordon, who we lost recently. My fellow poet friend, caring activist, community organizer, and fighter for a better life -may your loved ones know peace, and may they also know how much you were loved by the people you touched. Thank you for your poetry and your life that shined for others… I’ve been feeling a bit lost lately. Swimming in the sea of possibilities and circumstances. I am feeling the rush of time like I’m in a stolen car evading police, and although I enjoyed the newest Robert Redford movie, “The Old Man and The Gun” I hardly feel like the hero in this story. Perhaps because, as of late, people close to me have been hit quite hard by the disease -by Parkinson’s- in different ways; but it all feels the same, and that’s what makes it all the more painful. Whether it’s dropping down a level on the rungs of mobility, or worse, this disease is unrelenting and it waits for no man. There are clues and steps towards health, and studies for cures (thank you to those who study this for a living, adding valuable concrete evidence to people like me delving into the creative world to help people live healthfully by whatever means we know how). In essence, everyone who lives within the PD community, whether personally, peripherally, or those working to find a cure are all in search of the same thing. Understanding. The reasons for why this happens seems out of reach, as sometimes the reasons, “Why go on?” might feel just as far from one’s grasp. But understanding how to live the best way possible, how to live with the ups and downs or on’s and off’s, is probably the most vital key to happiness. And, I believe, in order to understand this disease, in order for me to continue on this trek of making a performance piece to teach others what it’s like, what it takes, and what connects us all, whether we have the disease or not, demands a closer look- closer than I’ve ever looked before... The theatre piece I conceived almost three years ago, has been co-written by folks with PD, and, like a good epic poem or play, drops you into the thick of it - of the disease’s repercussions - and doesn’t necessarily teach the audience anything. I’m not sure it should, for pedanticism can be perverse in the theatre, or maybe it’s what the theatre is made to do…? Suffice it to say, I at least want to engage the audience in something unique and semi-educational, something that puts them in the shoes of someone with PD. But how do you explain something that stems from something so fundamentally similar, and yet has so many distinct (read: varied) manifestations? I am slowly coming to the realization that perhaps it is the medical/scientific explanation for the disease, i.e. what happens within the brain’s Substantia Nigra that might help clarify things. Why not go to the source? Let’s go to those failing dopamine producing neurons, which is the issue at hand. Maybe that is what is needed to connect things, to actually show just that? To build something abstract at first, something seemingly “out there” - a conglomeration of dancers or actors moving about, perhaps in their own “dopaminergic” fashion -some language I create with the help of true science, resembling and recreating cellular metabolic activity, and/or neural activity to better create one of the choreographic languages or movement motifs of the piece… And perhaps after a long while, we see correlating movement themes among each person in the story, really focusing on the two main heroes of the play. Then we see shifts in these thematic elements - throughout the loss of dopamine and its varied effects - like transitions or chapter headers/closers, throughout key moments of shifting narrative points, i.e. like the first time someone falls, or if someone goes to the hospital and a test seems to suggest an infection), or a major stress develops. Once we develop an understanding of this new language being spoken, we might be able to share and develop that movement language to selectively tell a story without the use of dialogue or real life representations at all, but eventually with just movement. The movement disorder through movement. Maybe that is what this piece needs to connect it all, science through art. The representation therein being the tie that binds - ay, there’s the rub - that choreographic complexity. Perhaps I can really get to know the nitty-gritty of what happens to people on the inside. Deep inside their brains. Not just the symptoms, with which most of my teaching work revolve; not as therapy per say, but as an artistic means to set themselves free and approach their own bodies as creative beings, not patients with physical cues, but as dancers with imagery-driven, musical, and creative cues. Thus, in building the piece it might be easier to add science as the transitional scaffolding to the more narrative elements that act as the heart of the matter. This scaffolding will not try to represent symptoms, which is a tender subject and hard line to toe, but will represent the internal structures (perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of this disease) while depicting the effects of the disease on each individual involved. Most everyone will have witnessed the tremors, or the rigidity, bradykinesia, dyskinesia, festination before, but what they might not know is the cause of such things. To show them the inside in order to help us understand the outside. To provide cerebral context as a character. As a key player, in order to allow us to process the rest of the story. Devika As I continue to think about individual hydrogen protons, I’m reminded of a concept I learned in my physics classes: like electrons, these little positively-charged particles also have different energy levels, despite being confined to the atom’s nucleus (center) with the neutrons. So, I imagine a staircase with the first energy level at the bottom, the second energy level one step higher, and so on. These protons exist in only certain energy levels, and only a certain number can fit in each energy level. So, if hydrogen’s nucleus has only one proton, and if I imagine there are two hydrogen protons sitting on the same energy level (i.e., the first energy level), they both cannot be spinning in the same direction if they are to coexist on the same energy level. And this explains why one must spin parallel, while the other spins anti-parallel. While this is a simplistic way of explaining the energy levels of these atomic particles, it helps me understand their mobility and alignment differences. For MRI, mobile protons are of particular interest as the strength of the machine’s magnetic field determines their precession frequency, or the number of times the protons spin per second. Naturally, a stronger force will increase the precession frequency. This, in turn, helps me start choreographing the story of dancing hydrogen protons. So, if each dancer is to represent a hydrogen proton, I imagine two groups of dancers at either end of the stage. They enter spinning (a representation of precession) and meet in the middle. They don’t face each other, which is to illustrate the anti-parallel and parallel alignments. When I introduce the MRI machine, the dancers will need demonstrate the change in precession frequency. To best convey this, I am considering the use of instrumental music, as the vibrations of the machine’s metal coils reminds me of the sounds of a certain percussion instrument from India called the mridangam. Below are short mridangam recordings I found via Freesound, which is an open source database of sounds, that, to me, best capture the rhythmic vibrations in both the presence and absence of the magnetic field. The longer clip contains both slow and fast rhythmic beats and even has brief moments of silence (or stillness). It reminds me the sounds while protons have to align themselves in the direction of the magnetic field, while the shorter clip has more of a sustained rhythmic beat throughout the recording, and so, it reminds me of protons in their natural environment - in the absence of the magentic field.

Michael

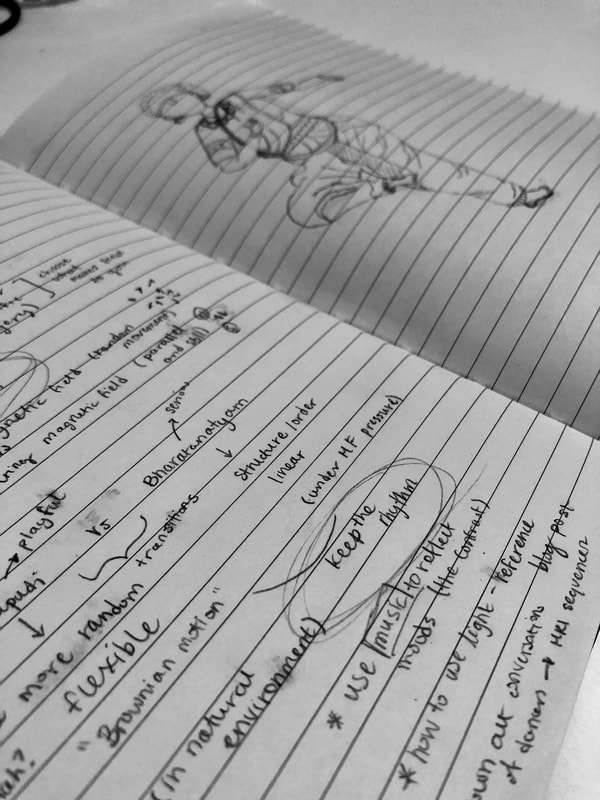

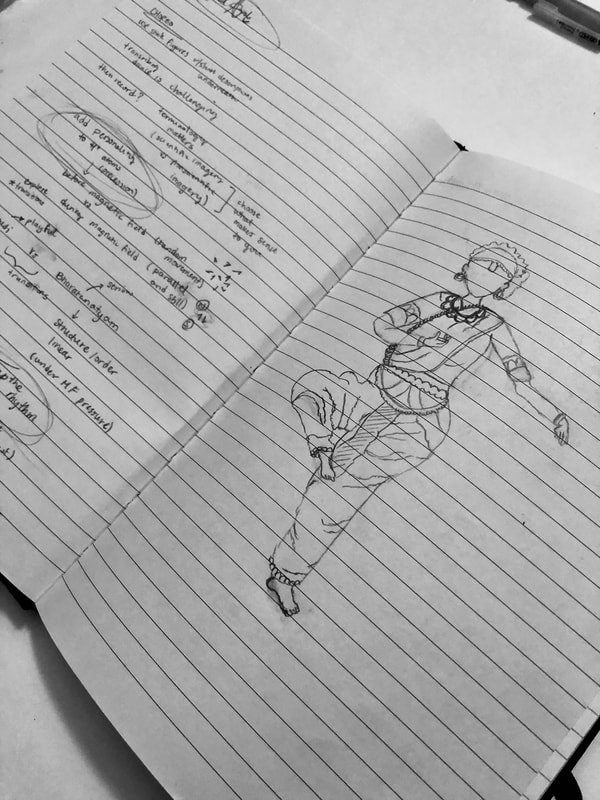

My focus has been locked on to this panel audition coming up – a portion of a performance piece I first conceived some three years ago, and part of which was choreographed and performed for “SharedSpace” at the Mark Morris Dance Center, back in the late Spring of 2017. It’s a story near and dear to my heart, and one that is co-authored by writers for the Brooklyn Parkinson Group. Even if it isn’t chosen for production, I am very glad to have breathed more life into it, and I’m very proud of my quartet of dancers who rose to the occasion. For this particular opening excerpt being presented for the panel, I’m honored to share some poetry and scenes from two spectacular writers, Joel Shatzky and the late Leonore Gordon. In keeping with the spirit of this piece, which is at once a dive into Parkinson’s Disease as well as a tale of lovers whose relationship paradigm shifts leaving one partner caring for the other; I’ve decided to bookend the performance with sounds every New Yorker knows all too well - sounds from the underground - the subway. Imagining a world where our main hero is one who may have walked among us, or is still among us. I’ve decided to record two poems within the ambience of underground, oncoming trains dovetailing or interrupting a particular last line, as if in a way that John Donne might appreciate, exemplifying that no man is an island and even, that train, it tolls for thee. The only instruments you hear (so far, if chosen I believe I will add percussion to a moment in the middle) is my guitar being plucked and strummed, in a rather folksy take on the 12 bar blues. And then later, the guitar in marriage with a Fender Rhodes piano, played by music director Chris Alexander. For this pair of instruments I wrote a song after a poem by John Kavanaugh, a former Catholic Priest and philosophical writer. A poem I felt captured a sense of longing in both the singer and the subject. A sense of longing, perhaps from isolation to connection, but mostly a love song, and a song of courtship - how our main couple met. I’ve personified the musculature during off periods versus on periods - moments of tension and freedom - with contractions and pronation of the upper and lower extremities versus extension through the spine and supination of the aforementioned limbs. The younger couple artistically depicts what the man’s balance and coordination systems might be going through during his routine exercises like marching in place and balancing on one leg, with precarious one legged moves, utilizing themselves or each other to balance and move from leg to leg. Therefore, they embody his internal structures on a macro level. I’m looking forward to spending more time on the phone with Devika after this Wednesday is behind me, and seeing where we might further connect. Her talks on MRI machines instill within me a desire to make more artistic choices influenced by the science behind routine and lifesaving radiology visits encountered throughout one’s life with Parkinson’s. How might we be able to develop a sense of clarity and precision within choreography or music, or chaos and disharmony, into unity? How can we make an audience, who may not know much about these types of screenings, aware of their amazing capacity to create beautiful images, with clarity and thus more complexity - something once impossible to ascertain in parts of the human body. Devika During our most recent Skype conversation, we discussed the challenges associated with transcribing dance, particularly when trying to choreograph a scientific concept. Once a topic has been decided, a route many take is drawing stick figures and scribbling short descriptions underneath. Yet, as Michael pointed out, terminology matters. That is, it’s important to select words that makes sense to you, especially when describing scientific imagery along with non-scientific imagery. So, when considering hydrogen protons, their ability to spin around an axis reminds me of “little planets.” Like earth, these “little planets” each have their own magnetic field, because a moving electrical charge (i.e., a proton) is an electric charge, which induces a magnetic field. To describe this behavior using non-scientific imagery, the following come to mind: “random,” “flexible,” “freedom,” and “almost playful.” However, when exposed to an external magnetic field (i.e., MRI machine), these protons will align parallel or anti-parallel in the direction of the external field. These two types of alignment are on different energy levels: parallel requires less energy and is the preferred state, while anti-parallel demands more energy. It’s similar to walking (or dancing) on your feet versus walking (or dancing while) on your hands - they are both are on different energy levels, because walking (or dancing while) on your hands requires much more effort. Non-scientific phrases to describe this phenomenon include: “stillness,” “need for structure,” “order,” and “desire for perfection.” This is interesting to consider - while dancers crave for flexibility and the creative freedom to move as they please, under certain (strict) conditions, remembering to be still and to only move in a linear fashion can be just as desired. Hence, the need for perfection carries as much value as the desire for playfulness. (The images below are of my notes from my Skype meeting with Kate and Michael, and the pose shown by the dancer is a reflection of this balance between stillness and creative freedom.) Michael

I spent some time down South visiting my family, and the nature in the backyard overtook my imagination for a spell in between thoughts on choreography, color theory, and conceptual presentation techniques. There was a young doe, and then many, blue jays, and a woodpecker, unseen birds too, and chipmunks and squirrels. All taking their respective turns in what may have appeared to be the chain of nutritious events. I first spotted the deer in the crook of two fences, where our old swing set used to be. I suppose she felt safe there, because after that I noticed her back left leg was injured. She ate with a seemingly joyous fervor, but a keen eye and outwardly turned ears towards unseen trouble.There was a veritable city outside this old Bay Window, as I sat stock-still. Movement is life. Whether dancers are representing body systems like the musculoskeletal, neural, emotional, or visual ones, any physicalized depiction or personification of said systems might resemble each other or simply become a lifeless wash of gestures, unless particular attention is put on contextual setup and audience knowledge. I believe in a strong narrative thread to keep an audience engaged and, like in literature, an allusion is only successful if an audience can understand it, so in that regard, an illusion on stage demands the some from both practitioner and participant. And, utilizing the root word of participant for an audience is my choice and my philosophy - perhaps even taking this idea to the point of immersive or participatory art, or at least one step akin to those ideals. If a audience’s engagement is aggrandized to the point of involvement or a point of participation, perhaps empathetic understanding might be achieved. Engaging the minds as well as the hearts of an audience is my aim while also educating them in someone’s struggle, someone’s story, and eventually settling into the fundamental truths that may reveal themselves between us all. Choosing between body systems before, during, or after medical procedures; or before, during, or after medication metabolization; or even before, during, or after dopamine loss is going to be a challenge - especially in the face of depicting a mysterious movement disorder on stage. For one, Parkinson’s grasp is as distinct as it is diverse. There are so many iterations of the same disease, especially when considering the long expanse of stages and symptoms. Behind certain unique symptoms are unexplained sources of such ailments. Medications for example can leave people with a variety of extra symptoms, and some people will undoubtedly eventually ride the waves of bradykinesia and dyskinesia, or slowness of movement versus the involuntary, extraneous movement that might result as a long-term effect on alternate dopamine therapies. I was chosen to present my work for a panel at a really amazing Dance and Performance organization called Gibney in a couple weeks, (in hopes to be produced there in the coming months) so I will remount the Prelude to the piece I’ve been co-writing with a few members of the Brooklyn Parkinson Group I’ve so far entitled “Basal Ganglia: notes from the underground.” I hope to create clearer stage pictures for personifying body systems, such as when one couple represents the musculature of the man with Parkinson’s who is doing exercises and getting a massage, a regular occurrence for this community. Simultaneity, or at least synchronicity, must be achieved between both couples, while not exactly doing the same gestures. Movements must mirror each other in qualitative efforts, while particular attention must be paid to intensity, proximity, and durational efforts. Also, this piece takes us on the journey and depiction of other symptoms such as sleep disturbances and dyskinesia. Even emotional aspects of the disease like depression, isolationism, and irritability. As I close out this entry for the week, I know there is still life outside this Window, but it’s dark o’clock and I can only see myself where once a Dogwood stood proving a nice playground for many a bird. Even though I cannot see them, I can hear some of the night’s animals quite well. Crickets, and locusts, and other humming insects unbeknownst even to this Eagle Scout. But I do know, like the molecular structures within my neural networks, they’re buzzing along. What I don’t realize at first, but do upon further inspection, is that my brain’s neural activity will actually increase tonight while I sleep - at least I hope so! - and within my lifeless looking body, within that stillness, there will be storms brewing, and mountains shifting, a veritable forest of diligent dealings, and daily disposals of things I don’t need. To the 60,000 people in America, and the 10 million plus people around the world who have Parkinson’s Disease... to the unseen many out there both thriving and fighting, and even suffering in silence, please know that you are felt. If not seen or heard, you are felt. |