Gianluca Bianchino

Interview by Kate Schwarting, Programs Manager

KS: On your website you state your work "is an attempt to contain chaos in an ordered aesthetic". What is your process for exploring this concept while utilizing elements of science and architecture?

GB: I regularly inform myself about science, but what I learn is rarely applied to an artwork in any direct capacity. Rather, scientific inquiry lurks in the background affecting my decisions in ways I cannot predict. I studied architecture in Italy before transitioning to fine art. As a student I considered it a discipline founded on achieving stability and order, but as a visual artist I realize the influence of architecture has assisted me in building impromptu organic structures that have made me question my own preconceived notions about order.

My general feeling is that things are always slipping away. You lay down a plan to create a stable path and as the saying goes -life happens while you make those plans. I think this dichotomy of order/disorder plays an important part in my practice and most visibly in my installations. When I initiate a project I install pockets of material as if I were planting seeds in certain areas of the wall or supporting structure. While every decision I make is executed with a sense of draftsmanship and craft, the configurations that emerge tend toward dispersion, particularly near the edges of most compositions. I feel involved in a push/pull relationship with the artwork in which entropy always prevails in the end. The forms I create often make me think of the slow transformations of celestial bodies but also cracks on the Earth’s surface resulting from an earthquake. Eruptive events you can observe but can’t control. I think my work is the result of personal earthquakes presented in super slow motion using geometric abstraction as the narrative language. Nature has an underlining geometry and possibly so does our thought process, even at its most chaotic. Perhaps the attempt to contain chaos happens ultimately in the artwork’s expanded experience of time, in which an event can be interpreted as a structure, one suggesting continuous motion while frozen in its physical essence.

GB: I regularly inform myself about science, but what I learn is rarely applied to an artwork in any direct capacity. Rather, scientific inquiry lurks in the background affecting my decisions in ways I cannot predict. I studied architecture in Italy before transitioning to fine art. As a student I considered it a discipline founded on achieving stability and order, but as a visual artist I realize the influence of architecture has assisted me in building impromptu organic structures that have made me question my own preconceived notions about order.

My general feeling is that things are always slipping away. You lay down a plan to create a stable path and as the saying goes -life happens while you make those plans. I think this dichotomy of order/disorder plays an important part in my practice and most visibly in my installations. When I initiate a project I install pockets of material as if I were planting seeds in certain areas of the wall or supporting structure. While every decision I make is executed with a sense of draftsmanship and craft, the configurations that emerge tend toward dispersion, particularly near the edges of most compositions. I feel involved in a push/pull relationship with the artwork in which entropy always prevails in the end. The forms I create often make me think of the slow transformations of celestial bodies but also cracks on the Earth’s surface resulting from an earthquake. Eruptive events you can observe but can’t control. I think my work is the result of personal earthquakes presented in super slow motion using geometric abstraction as the narrative language. Nature has an underlining geometry and possibly so does our thought process, even at its most chaotic. Perhaps the attempt to contain chaos happens ultimately in the artwork’s expanded experience of time, in which an event can be interpreted as a structure, one suggesting continuous motion while frozen in its physical essence.

KS: Your series "Transportals" requires viewers to interact with the optics and view it at very close proximity. How does these and other interactions create or support meaning in your work?

GB: The optical component of “Transportals” may appear to be the dominant feature, and for viewers willing to be entertained by an artwork it certainly can be. However, these works were conceived to play on duality in several ways relevant to my practice: geometric vs organic, sculpture vs painting, two dimensional vs three dimensional; all strictly formal visual elements overlapping and coexisting to suggest the space that surrounds us has far more dimensions than meets the eye. The outer shells of these sculptures, sometimes reminiscent of analog medium format cameras, are designed in hard edge geometric fashions while the worlds contained within are executed like organic abstract paintings. Here is where I allow the lens, the bridge between the two realties, to do its magic; it activates the internal part of the work surprising the viewer with an unexpected expansive view into a dotted realm of layered material. As if the initial impact were not dramatic enough the viewer’s eye learns quickly that it can interact with this internal space via cross focusing and shifting vantage points. This is perhaps the moment in which the viewer turns the art object into an instrument. This illusionary depth of field has worked especially well when exhibited in the now common small galleries typical of New York’s Lower East Side and Brooklyn. Squished by the wine sipping art goers starving for the next fleeting connection at most openings, an inquisitive viewer can elbow their way through the crowd lured by the calling of a psychedelic moving image produced by the lens when standing at distance (like a peering eye with a lava lamp quality to its surface) only to discover a portal that takes them, for as long as they are willing to explore, into an alternate dimension.

GB: The optical component of “Transportals” may appear to be the dominant feature, and for viewers willing to be entertained by an artwork it certainly can be. However, these works were conceived to play on duality in several ways relevant to my practice: geometric vs organic, sculpture vs painting, two dimensional vs three dimensional; all strictly formal visual elements overlapping and coexisting to suggest the space that surrounds us has far more dimensions than meets the eye. The outer shells of these sculptures, sometimes reminiscent of analog medium format cameras, are designed in hard edge geometric fashions while the worlds contained within are executed like organic abstract paintings. Here is where I allow the lens, the bridge between the two realties, to do its magic; it activates the internal part of the work surprising the viewer with an unexpected expansive view into a dotted realm of layered material. As if the initial impact were not dramatic enough the viewer’s eye learns quickly that it can interact with this internal space via cross focusing and shifting vantage points. This is perhaps the moment in which the viewer turns the art object into an instrument. This illusionary depth of field has worked especially well when exhibited in the now common small galleries typical of New York’s Lower East Side and Brooklyn. Squished by the wine sipping art goers starving for the next fleeting connection at most openings, an inquisitive viewer can elbow their way through the crowd lured by the calling of a psychedelic moving image produced by the lens when standing at distance (like a peering eye with a lava lamp quality to its surface) only to discover a portal that takes them, for as long as they are willing to explore, into an alternate dimension.

Gianluca Bianchino, Transportal 6 -Beyond the Singularity, Mixed media sculpture, 8” x 8” x 9”, 2016

Gianluca Bianchino, Transportal 6 -Beyond the Singularity, Mixed media sculpture, 8” x 8” x 9”, 2016

KS: You employ many materials but light and optics seem have significant importance. What is its role in exposing and exploring the perspective of the viewer and the geometry that is central to your work?

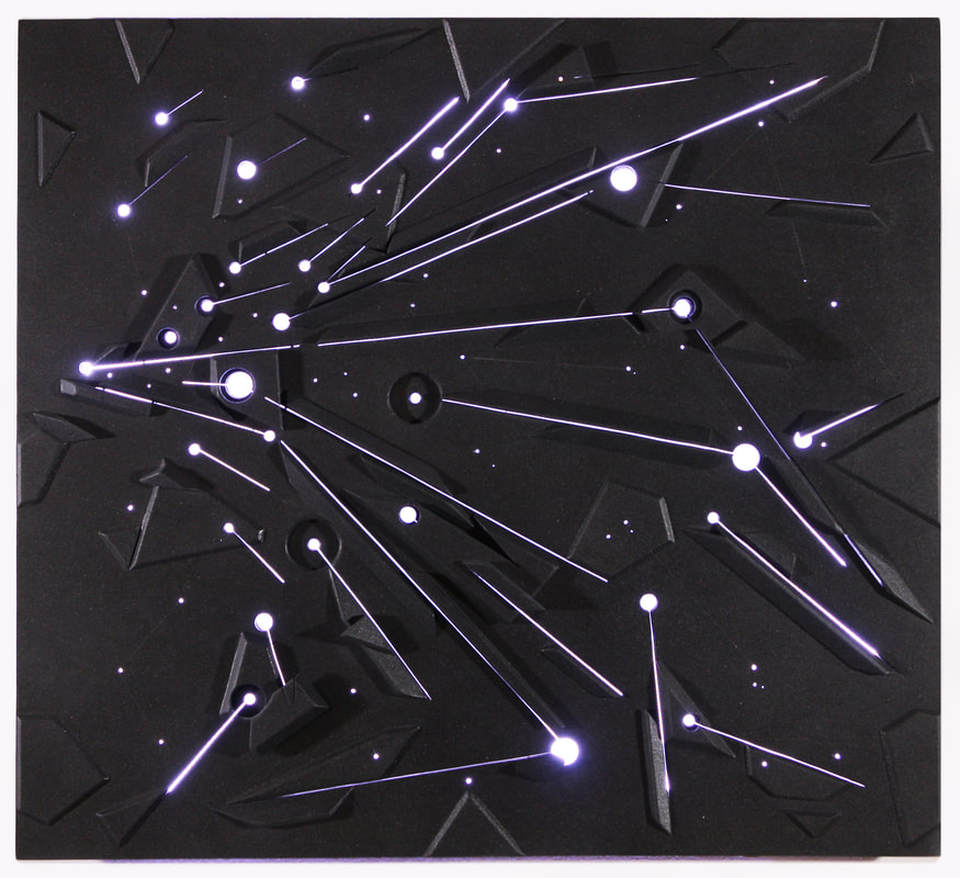

GB: Light and optics have offered the opportunity to engage the viewer beyond the visceral. In my series “Lightmaps” the kinetic-optical quality of the work is suggestive of light moving through space; while the light within the work is actually static the surface becomes activated by the viewer moving in relationship to the object. This intended interaction is loosely inspired by Einstein’s theory of relativity specific to how the position of the observer (the viewer) determines the perception of a celestial body and its related experience of time. From a purely artistic stand point it is a way to engage the viewer in modulating a drawing of lines and dots of light that I can only describe as an interactive star map of some kind where sculpture once again flirts with the idea of becoming an instrument for exploration. “Lightmaps” may be my most deliberate employment of a scientific theory, or data, thus far, because some of these works are actually based on accurate star charts. However, even so, the idea was born from from process and happy accidents in the studio, working with unfamiliar materials and examining the properties of light. In some works, graphite lines and shapes are applied to create a related effect generated by reflected ambient light. If the power goes out the surface is still active.

If you are not a scientist it seems that art is one of the better disciplines by which theories can be tested or experienced somehow, though through experiments not necessarily intended to prove the empirical, but rather conceived to create alternate gateways of perception and understanding of the complex nature of space.

GB: Light and optics have offered the opportunity to engage the viewer beyond the visceral. In my series “Lightmaps” the kinetic-optical quality of the work is suggestive of light moving through space; while the light within the work is actually static the surface becomes activated by the viewer moving in relationship to the object. This intended interaction is loosely inspired by Einstein’s theory of relativity specific to how the position of the observer (the viewer) determines the perception of a celestial body and its related experience of time. From a purely artistic stand point it is a way to engage the viewer in modulating a drawing of lines and dots of light that I can only describe as an interactive star map of some kind where sculpture once again flirts with the idea of becoming an instrument for exploration. “Lightmaps” may be my most deliberate employment of a scientific theory, or data, thus far, because some of these works are actually based on accurate star charts. However, even so, the idea was born from from process and happy accidents in the studio, working with unfamiliar materials and examining the properties of light. In some works, graphite lines and shapes are applied to create a related effect generated by reflected ambient light. If the power goes out the surface is still active.

If you are not a scientist it seems that art is one of the better disciplines by which theories can be tested or experienced somehow, though through experiments not necessarily intended to prove the empirical, but rather conceived to create alternate gateways of perception and understanding of the complex nature of space.

KS: What projects or exhibitions are you currently involved in?

GB: At this time I am primarily focused on “Uncharted Space”, a solo exhibition curated by Midori Yoshimoto which will take place in January 2019 at the Visual Art Gallery of New Jersey City University, in Jersey City. This is where I received my BFA in painting almost twenty years ago. As alumni of the program it is an honor to have been offered this exhibit. The scale of the gallery provides an opportunity to work in several formats, including sculpture and installation. Recent optical sculptures will be coupled with site specific interventions inspired by tectonic activity. While astronomy is always an inspiration, my recent travels keep bringing me back to my homeland in Southern Italy, a hot spot for earthquakes and volcanic activity.

Being Italian to most people means having a connection with ancient rituals and traditions. For me this identity lies more so in how an active and untamed terrain has shaped my experience as an immigrant and traveler. Science continues to inform my artistic relationship with the forces of nature. Somehow in this creative endeavor, which promises to be multimedia based, earth will meet sky.

GB: At this time I am primarily focused on “Uncharted Space”, a solo exhibition curated by Midori Yoshimoto which will take place in January 2019 at the Visual Art Gallery of New Jersey City University, in Jersey City. This is where I received my BFA in painting almost twenty years ago. As alumni of the program it is an honor to have been offered this exhibit. The scale of the gallery provides an opportunity to work in several formats, including sculpture and installation. Recent optical sculptures will be coupled with site specific interventions inspired by tectonic activity. While astronomy is always an inspiration, my recent travels keep bringing me back to my homeland in Southern Italy, a hot spot for earthquakes and volcanic activity.

Being Italian to most people means having a connection with ancient rituals and traditions. For me this identity lies more so in how an active and untamed terrain has shaped my experience as an immigrant and traveler. Science continues to inform my artistic relationship with the forces of nature. Somehow in this creative endeavor, which promises to be multimedia based, earth will meet sky.