George Shortess

Interview by Emma Snodgrass, Intern

ES: Your early work was extraordinarily innovative and is echoed by current sciart concepts. How did you end up merging fields in the seventies?

GS: I had been following a major career path in cognitive neuroscience with a Ph.D. from Brown University in experimental psychology, post-doctoral training in neurophysiology, research grant support from the National Institutes of Health, with a professorship at Lehigh University, etc. The emphasis here was on the neurophysiological basis of vision and visual perception. However at the same time, I had studied studio art at the University of Hawaii and the University of Rhode Island, and completed a foundation program in studio art with an emphasis on painting and drawing at the Boston Museum School. I continued to practice and develop my art while pursuing the cognitive neuroscience career. The focus of my art was on landscape painting, although I had experimented with some other areas including paintings with copper pipes and enamel on copper. Until the mid-seventies, however, these interests were practiced in parallel. I was doing both and there was no overlap.

At this time I reached a point where in order to continue my basic research in neurophysiology of vision I would need a major retooling of my experimental techniques. At the same time my art work was commanding a major part of my attention. As a result I decided to try to merge my neurophysiologically based interests in vision and perception with my art work. One of the appeals of this decision was that my life would be more integrated, but the challenges of combining them were intriguing, since I knew of no one else who was doing this sort of thing. There were a few neuroscientists who were interested in how the nervous system might process art related events, but no one, as far as I knew, was making art that explicitly combined the two areas.

Interview by Emma Snodgrass, Intern

ES: Your early work was extraordinarily innovative and is echoed by current sciart concepts. How did you end up merging fields in the seventies?

GS: I had been following a major career path in cognitive neuroscience with a Ph.D. from Brown University in experimental psychology, post-doctoral training in neurophysiology, research grant support from the National Institutes of Health, with a professorship at Lehigh University, etc. The emphasis here was on the neurophysiological basis of vision and visual perception. However at the same time, I had studied studio art at the University of Hawaii and the University of Rhode Island, and completed a foundation program in studio art with an emphasis on painting and drawing at the Boston Museum School. I continued to practice and develop my art while pursuing the cognitive neuroscience career. The focus of my art was on landscape painting, although I had experimented with some other areas including paintings with copper pipes and enamel on copper. Until the mid-seventies, however, these interests were practiced in parallel. I was doing both and there was no overlap.

At this time I reached a point where in order to continue my basic research in neurophysiology of vision I would need a major retooling of my experimental techniques. At the same time my art work was commanding a major part of my attention. As a result I decided to try to merge my neurophysiologically based interests in vision and perception with my art work. One of the appeals of this decision was that my life would be more integrated, but the challenges of combining them were intriguing, since I knew of no one else who was doing this sort of thing. There were a few neuroscientists who were interested in how the nervous system might process art related events, but no one, as far as I knew, was making art that explicitly combined the two areas.

|

ES: Your ongoing interactive Neural Art project foreruns the emergence of neuroaesthetics as a field of research. Are there any recent developments in neuroscience that have greatly impacted your neural art?

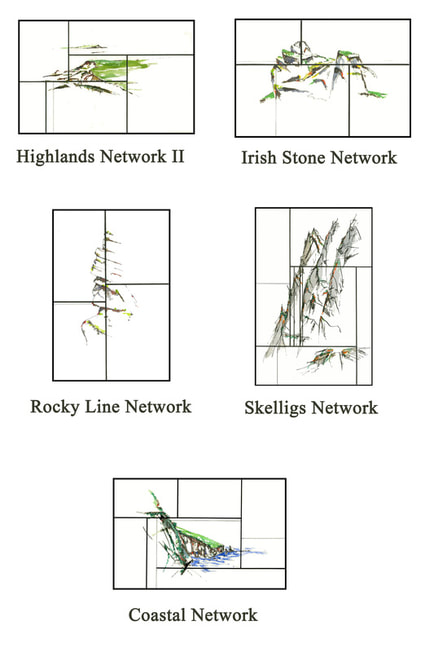

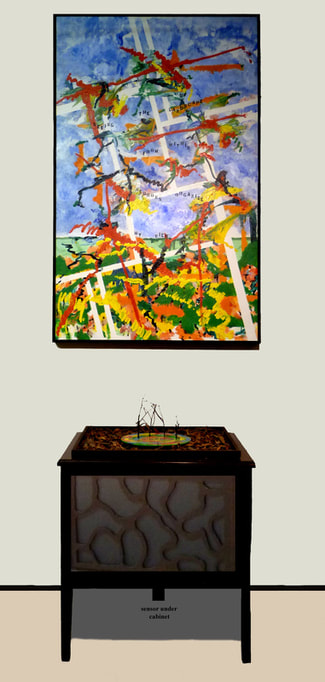

GS: While I have certainly kept up with neuroscience and neuroaesthetics and continue to find it fascinating, no specific developments have had a unique impact. My Neural Art is based on fundamental conceptual aspects of the nervous system, such as its interactive nature and its network structures. I have also emphasized its role as the interface between the outside world and our inner experience and its ability to organize this world coherently. Recent developments have reinforced the importance of these concepts, and I continue to find ways to incorporate them in my work. My early Neural Art work was very conceptual in nature, in which I asked people to conceptualize the nervous system as a work of art. As my ideas developed my work became more concrete and I began to do paintings and interactive sculptures. The early sculptures generate the sounds of simulated nerve impulse patterns in response to the movements of the viewers. The paintings are generally based on the idea that the nervous system is the interface between our inner experience and the external reality. I overlapped scenes, both natural and constructed, with various types of grids, to create the feeling of looking through the grid (the nervous system) at the world. Some grids were rectilinear black lines, while others were the absence of pigment. Still others became more organic in nature. In my most recent work, an interactive sculpture entitled Seeing the Landscape from Within, I hung one of the grid paintings over a small cabinet that housed a speaker, a sampler and a miniature computer. Hidden under the cabinet is a movement sensor which when activated by viewers’ movements generates voice segments through the speaker. There are 24 segments that speak to the nervous system as the interface that organizes and determines our perception of this kind of environment. Each time a viewer triggers the system, two to five segments are selected randomly and played, with some overlap, producing an impression rather than a linear train of thought. |

|

ES: How has disciplinary differentiation shaped how you have gone about communicating your work?

GS: I have found many traditional art venues resistant or even hostile to the idea of my art work based on the nervous system. This is due, I think, to a variety of reasons. The nervous system is not a traditional subject like landscape, portraiture, or still life. There is also a lack of understanding of the nervous system, so it is unclear if my work truly reflects the nervous system. In addition my art is viewed as intellectual rather than as emotional and thus is not art in the way that they define it. However, there have been others who have embraced the idea. The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts has twice awarded me artist fellowships that were based in part on developing my neural art ideas. And there have been gallery directors who have offered me one man exhibits centered on this work. The response of viewers has been quite mixed. Some, of course, are quite taken by it and find it very satisfying. Others are puzzled and are not willing to accept it as art. In my interactive sculptures, it often is unclear how they work and what is causing the sounds. There have been a significant number of viewers who respond to the work by trying to figure out how it works, which I suppose is not significantly different from trying to figure out how a painter, for example, produces a remarkable likeness. I have not rejected traditional art. Since landscape painting was a major part of my original motivation for studying painting, it is still an important part of my artistic life, and I continue to make and show this work. It provides a different type of satisfaction and pleasure. |