Danielle Ezzo

Interview by Alexandra Constantinou, Communications & Web Intern

AC: On your website, you describe your practice as the combination of "the historical, technological and the ever-growing “new aesthetic” and how it meets the human form." Could you elaborate on this?

DE: I’m very interested in the lifespan of photography. From it’s inception, the medium has been intrinsically tied to technology and the sciences. There are cameras that can see into space at planets and stars that go unseen with the naked eye and into microscopic worlds within the and body. It’s power to see things they were previously unseeable catalyzed so many fields of inquiry turning them into industries. The Industrial Revolution and the years leading up to it, were incredibly exciting in terms of innovation; uncharted territories were being discovered and documented for the first time.

Now, we live in an age where seemingly everything has been photographed, and yet photography continues to look forward into the unknown. My practice is about chasing those unknown territories and tapping into the feeling of curiosity; photographing the un-photographable.

There’s a lot of interest now in digital technologies and how they change the landscape of photography. I’m specifically interested in how some of these technologies work and express themselves visually, but also how that changes how we view ourselves.

Interview by Alexandra Constantinou, Communications & Web Intern

AC: On your website, you describe your practice as the combination of "the historical, technological and the ever-growing “new aesthetic” and how it meets the human form." Could you elaborate on this?

DE: I’m very interested in the lifespan of photography. From it’s inception, the medium has been intrinsically tied to technology and the sciences. There are cameras that can see into space at planets and stars that go unseen with the naked eye and into microscopic worlds within the and body. It’s power to see things they were previously unseeable catalyzed so many fields of inquiry turning them into industries. The Industrial Revolution and the years leading up to it, were incredibly exciting in terms of innovation; uncharted territories were being discovered and documented for the first time.

Now, we live in an age where seemingly everything has been photographed, and yet photography continues to look forward into the unknown. My practice is about chasing those unknown territories and tapping into the feeling of curiosity; photographing the un-photographable.

There’s a lot of interest now in digital technologies and how they change the landscape of photography. I’m specifically interested in how some of these technologies work and express themselves visually, but also how that changes how we view ourselves.

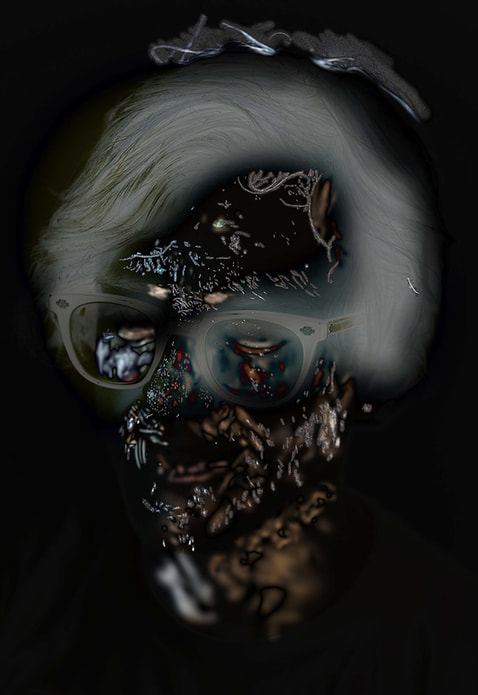

AC: Your work challenges the traditional definition of a photograph. In your recent projects, Phantom Limb and The Intentional Object, some of the photos are barely recognizable as human. How did you develop this style?

DE: Along with being trained as a photographer, I work as a retoucher in the fashion, beauty, and advertising industries. Both of these projects stem from a need to sever retouching from the original image as a way to see what alterations are actually taking place. With The Intentional Object, I remove the original pixel image, leaving a black background in it’s place. What’s left is a trace of a portrait and the elements that would often be removed, partially concealed, or altered. I choose to preserve only those parts.

With Phantom Limb, which I’m currently working on, I’ve built upon that process while strategically bringing back parts of the original image. It’s important to me that my subjects remain human and that the images are viewed in the context of photography and the photographic index. I focus less on the process of retouching and how it functions within the image, and more on the loose themes of human vulnerability and intimacy. Producing photos that expose only that things that most people would prefer to conceal is a vulnerable act for both the subject and the photographer. I’m interested in elevating the fragility of being human and highlighting the beauty in imperfection.

DE: Along with being trained as a photographer, I work as a retoucher in the fashion, beauty, and advertising industries. Both of these projects stem from a need to sever retouching from the original image as a way to see what alterations are actually taking place. With The Intentional Object, I remove the original pixel image, leaving a black background in it’s place. What’s left is a trace of a portrait and the elements that would often be removed, partially concealed, or altered. I choose to preserve only those parts.

With Phantom Limb, which I’m currently working on, I’ve built upon that process while strategically bringing back parts of the original image. It’s important to me that my subjects remain human and that the images are viewed in the context of photography and the photographic index. I focus less on the process of retouching and how it functions within the image, and more on the loose themes of human vulnerability and intimacy. Producing photos that expose only that things that most people would prefer to conceal is a vulnerable act for both the subject and the photographer. I’m interested in elevating the fragility of being human and highlighting the beauty in imperfection.

AC: In your projects, you write about Edmund Husserl and phenomenology. How did you discover phenomenology, and how has it affected your photography process?

DE: Philosophy has always been a point of inspiration for me. Many of my projects try to point to larger unanswerable questions about the human condition. I am fascinated by his proposal in phenomenology that sometimes things can only be experienced and not seen, at least not directly. Retouching is so pervasive that it becomes common place, yet the effects are felt in the ways that we view our bodies and how we shape our identities in an image-saturated culture.

DE: Philosophy has always been a point of inspiration for me. Many of my projects try to point to larger unanswerable questions about the human condition. I am fascinated by his proposal in phenomenology that sometimes things can only be experienced and not seen, at least not directly. Retouching is so pervasive that it becomes common place, yet the effects are felt in the ways that we view our bodies and how we shape our identities in an image-saturated culture.

AC: What are your plans for the rest of the year?

DE: I’m working on a two person pop-up exhibition also called "Phantom Limb," where I will be displaying images from both projects alongside the talented Sophie Kahn’s 3D printed sculptures. That takes place at Dose Projects in Brooklyn on December 15th.

DE: I’m working on a two person pop-up exhibition also called "Phantom Limb," where I will be displaying images from both projects alongside the talented Sophie Kahn’s 3D printed sculptures. That takes place at Dose Projects in Brooklyn on December 15th.