|

Tali

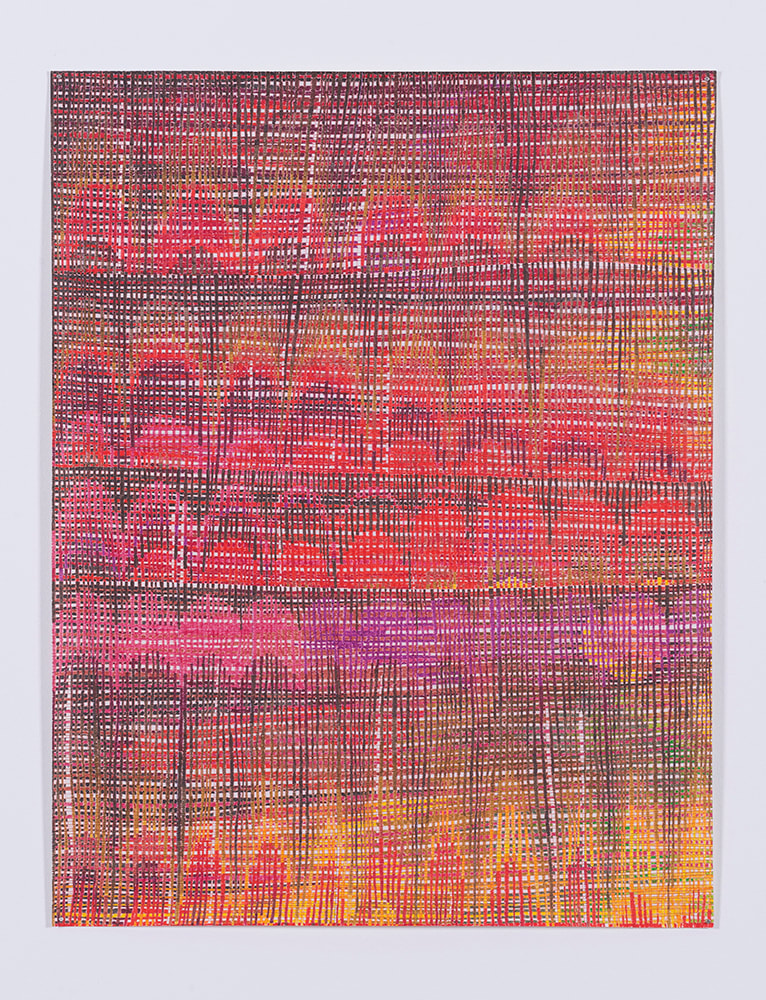

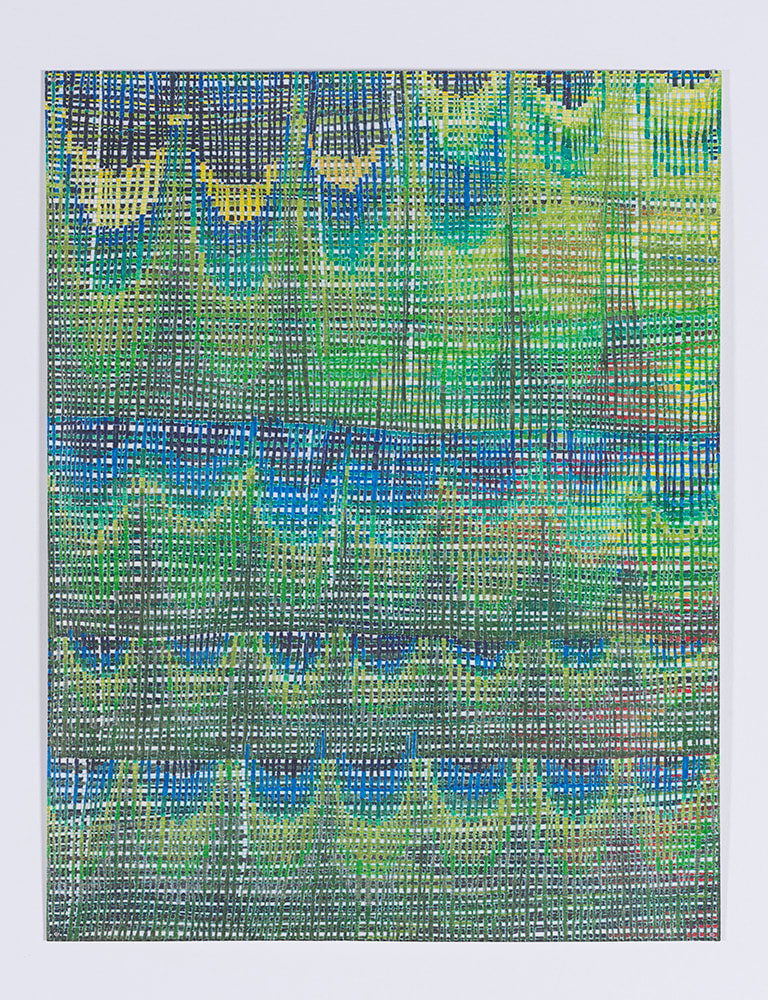

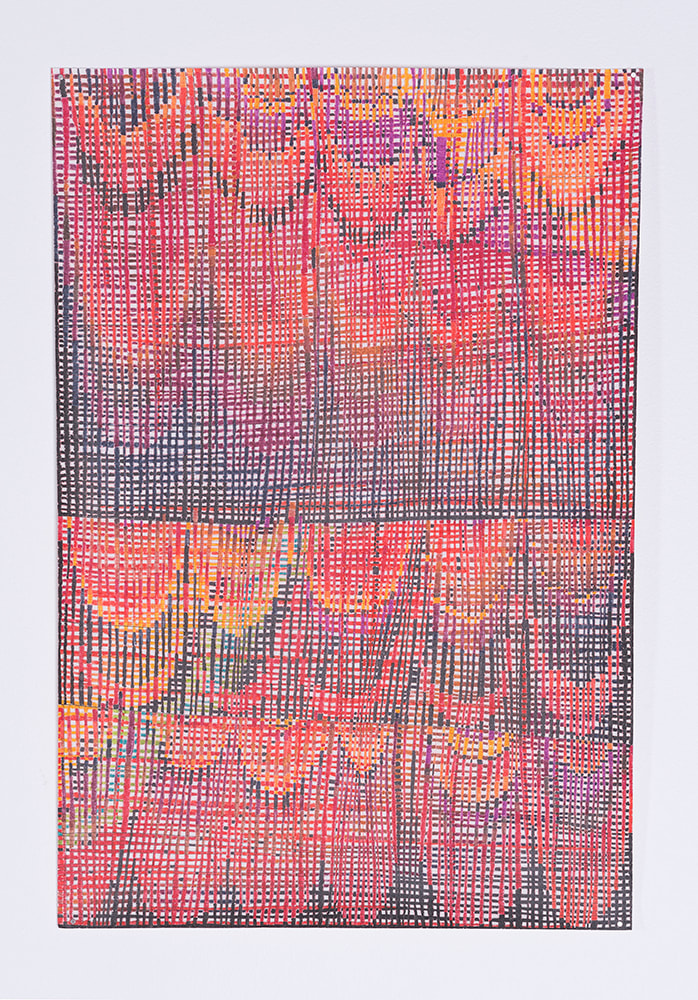

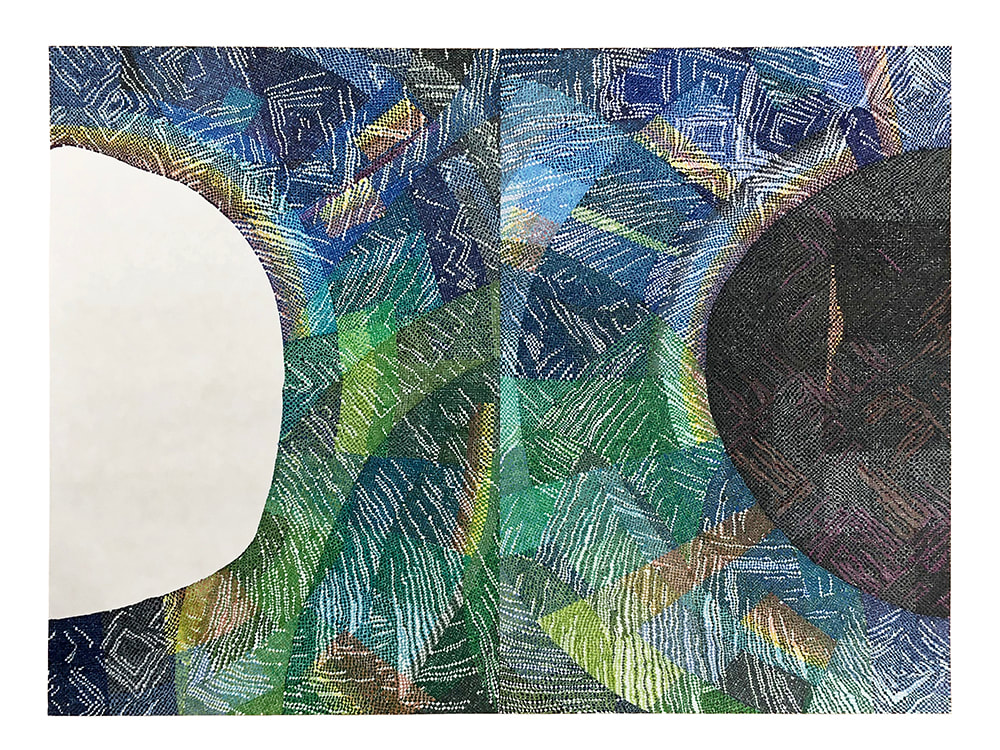

I have been thinking that drawing might be a good way to incorporate the varied layers and interconnecting systems and scales and lifeforms Oscar and I have been discussing. So today, I am sharing a few past drawings that I am thinking of as references. To me, these are a combination of landscapes, maps, weavings (with ink on paper), and journals. They evoke the flexibility of cloth and build on the mathematical patterning of weaving while also undermining the logic of weaving. Rules are created and broken. Systems are set in place and changed. I started this first set of drawings while listening to the news of the hurricanes, floods, and fires August - October 2017.

These drawings each record my experience of moving through a specific place and time.

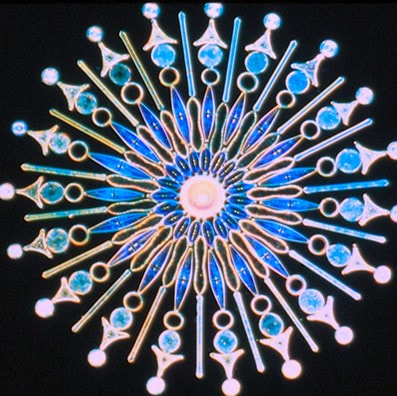

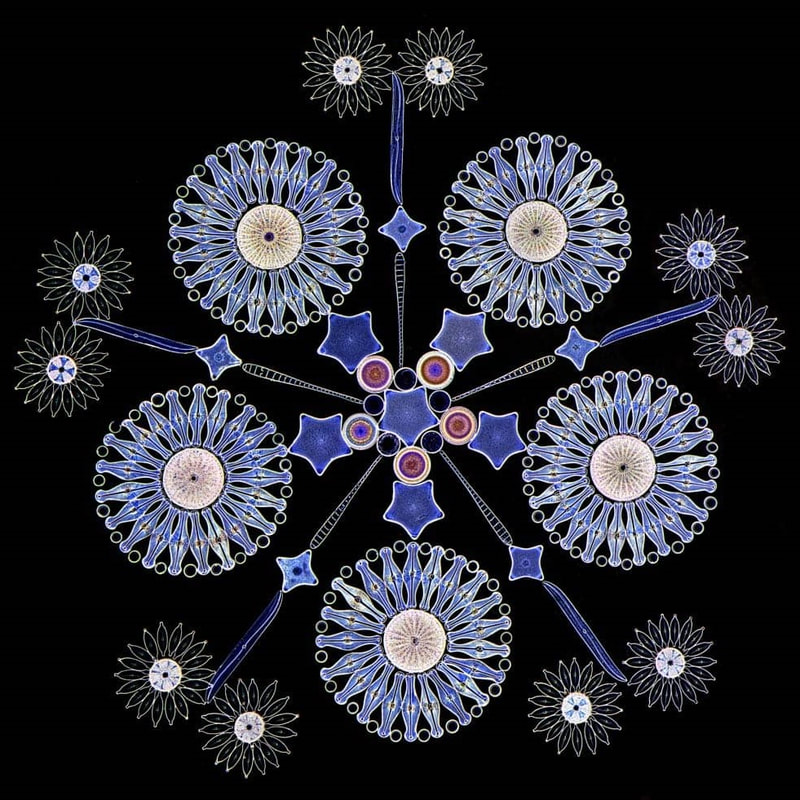

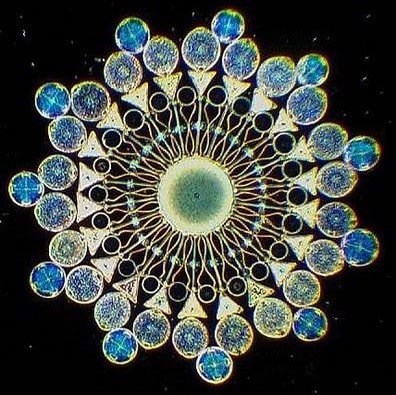

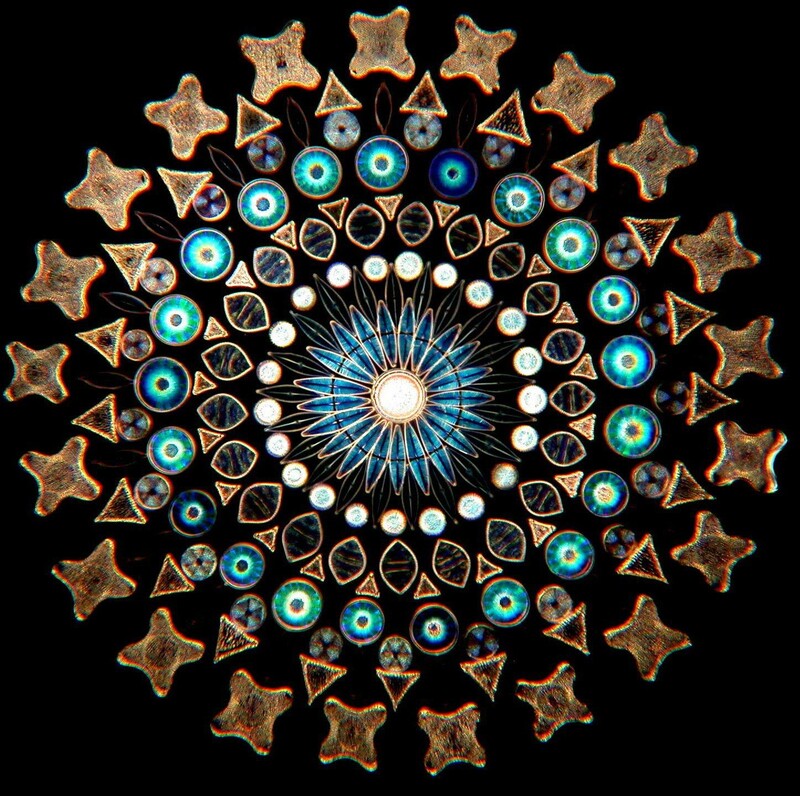

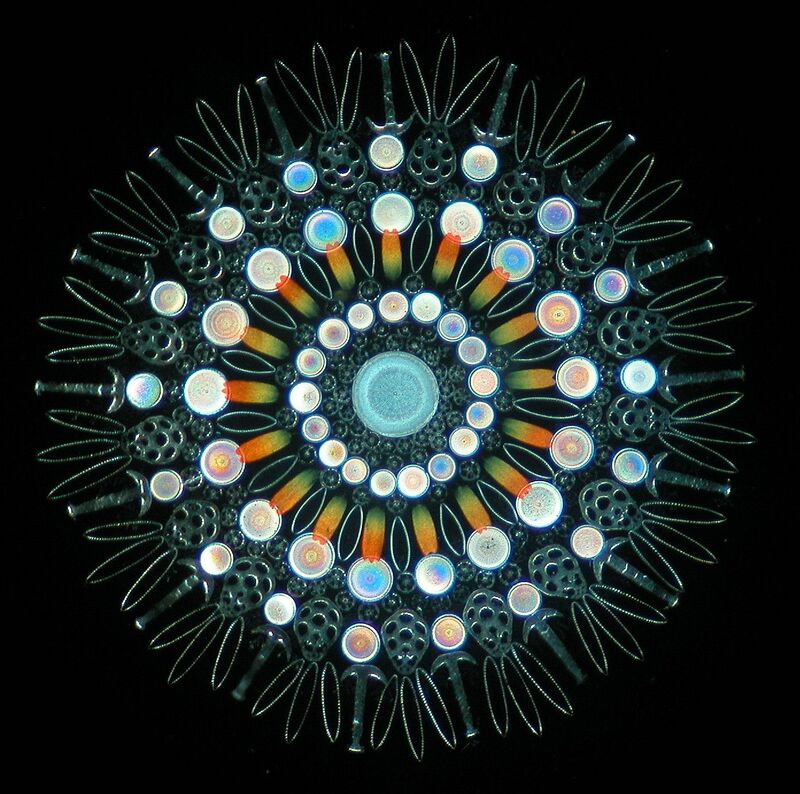

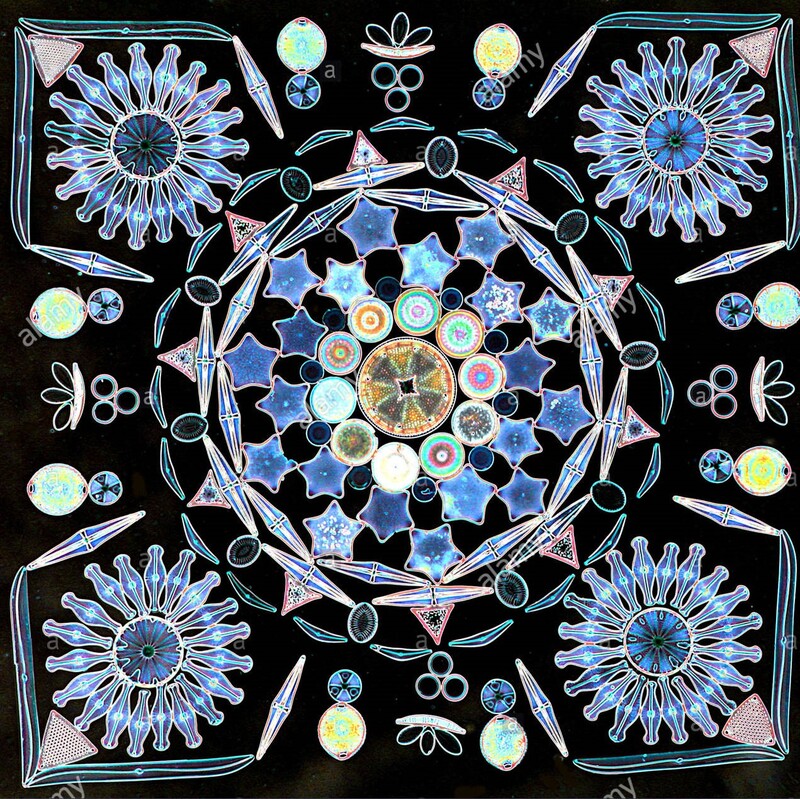

At age 16, Klaus Kemp came across a Victorian diatom arrangement and quickly became fascinated by these algae and the compositions created by these artists. Diatoms are algae (and therefore they grow their biomass from inorganic compounds and light) present in freshwater and marine environments. Diatoms are as diverse as beautiful (as Tali mentioned in her post last week), with some species living in open waters and other growing on sediments, rocks, and plant surfaces, some species forming colonies while others staying as isolated single cells. The most striking characteristic of these algae is their silica valves (like glass shells), the shape, size, and ornamentation of which are characteristic of each species (or group) and used for their identification. Each diatom species presents adaptations to live under specific nutrient, light, pH, and oxygen conditions, and the presence (or absence) of diatom species are often studied to track changes in aquatic environmental conditions.

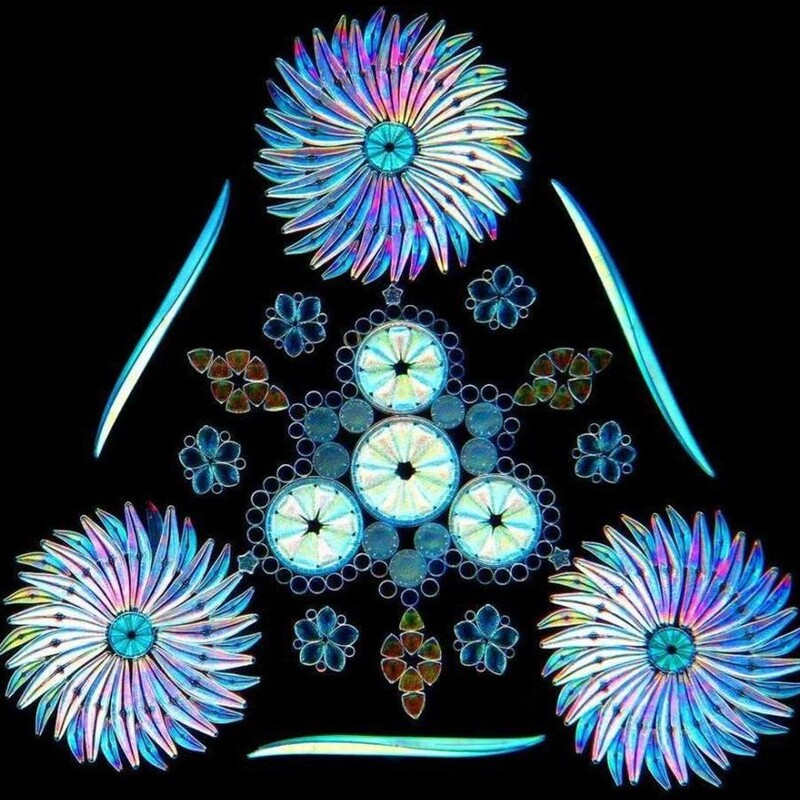

Klaus’ art often depicts diatoms in kaleidoscopic arrangements, carefully placing each cell in a pattern that emphasizes the diversity and beauty of these algae. These arrangements are almost “overwhelming. The variety and intricacy of shapes, patterns and repetitions evoke a profound sense of awe”. But there are more diatom arrangements than those made by Klaus. When diatoms die, they fall to the bottom of lakes and oceans, and since their shells are made of silica, they do not decompose, and remain as some sort of fossils, as an imprint of the conditions of past times. These fortuitous arrangements are equally beautiful in their own way, as they tell the story of lakes and oceans, and their surrounding environments.

Watching how Klaus works through the microscope, carefully picking and placing diatoms on a slide I am reminded of the work of scientists studying diatom records in lake and ocean sediments. I imagine Tali’s process being very similar, inspecting the data, carefully arranging it, and creating new narratives that evoke a profound sense of awe (as Klaus describes it). During our conversations, we continue sharing our techniques and the knowledge we gain from them, and while more similarities in our processes continue to arise, I become even more interested in all those parts that our work does not necessarily have in common, as these can be the trigger of new perspectives to explore and explain environmental and social change.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |