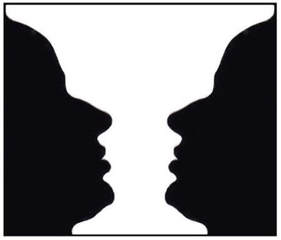

Kent So, my partner Jenny and I are starting to come up with some tangible ideas. That is to say; we are beginning to see what we will have produced by the end of this program. So as mentioned before, we are looking to harness two concepts. One concept we are exploring is the principle of double images within a picture to promote the idea of perspectives in science and art. This is one of the more well-known examples. What do you see? Two faces looking at each other or do you see a vase? Did you see both images right off or did you only see one until I mentioned the other? As mentioned in previous posts, this is an example of how we see the world. Sometimes we see one thing, then we might see things differently even though we are looking at the same object. However, once you see both images, you can’t un-see them. This is a concept we would like to promote in how students see science concepts as well as how they see their own abilities to understand them.  A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte Painting by Georges Seurat, 1886 A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte Painting by Georges Seurat, 1886 The next concept my partner and I are exploring is the principles of pointillism. Many times, students express frustration when they are taking classes that seemingly have no connection to where they have aspirations to be. They look at their day to day assignments as a series of unconnected dots. They don’t see how day to day concepts taught in class or series of classes they must take contribute to “seeing” a much bigger picture. Many students only see the seemingly random dots. Not realizing they make up a much larger picture. This picture is the understanding of a general concept. It is the sum of knowledge that makes one an “expert.” Some pictures are simple while some are much more elegant. My partner and I discussed creating a possible curriculum that could be implemented in a classroom utilizing these theoretical constructs to teach a given subject matter in the sciences. We are going to produce a video teaching from our respective disciplines, but from an overarching perspective of double images, while teaching the “dots” and showing how they contribute to a much larger “picture.” Jenny Scale has been popping up more and more in the discussions between Kent and I, particularly as we discuss the ability to simultaneously comprehend a painting as a collection of brush strokes or points as well as a unified landscape representation. In geology, scale is particularly useful as a concept that helps us frame and contextualize scientific questions. Although a geoscientist might choose a certain scale at which to explore a given problem, it’s likely they will necessarily work at multiple scales during the process of inquiry. For example, if one decides to study trace metal mobility at a basin-wide scale, one may find that the molecular kinematics of trace metals and small-scale soil processes deeply informs the behavior of trace metals at large scales. Sedimentary geologists use sediment flumes the size of a refrigerator to study and teach concepts relevant to massive rivers in the present day as well as strata deposited millions of years ago.

This highlights the importance of scale as not only a scientific tool, but a tool for explaining scientific concepts in the classroom. Teaching students that we use scale to simplify concepts at certain scales, while still acknowledging complexity at finer scales, might help students to connect the dots between fundamental scientific concepts and higher-order ideas. For example, I can explain the concept of pitch, with an A generally representing 440 Hz, in relatively simple terms. I can then use this understanding as a basis for explaining that many orchestras have been gradually creeping up in pitch over the past hundred years, and that each player humming on the same note in an 80-person orchestra is probably playing 445 a few micro-cents differently. Or, I might choose to explain the effect of temperature and humidity on musical instrument and the phenomenon of brass and wind instruments sinking in pitch as string instruments rise. In general, the way we comprehend and interpret our world is incredibly dependent on scale. This week, I challenge you (and myself) to think more about how you work with scale in your own life.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |