0 Comments

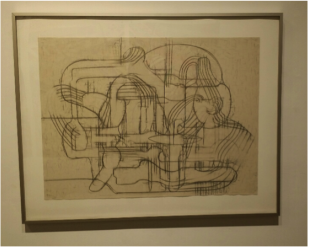

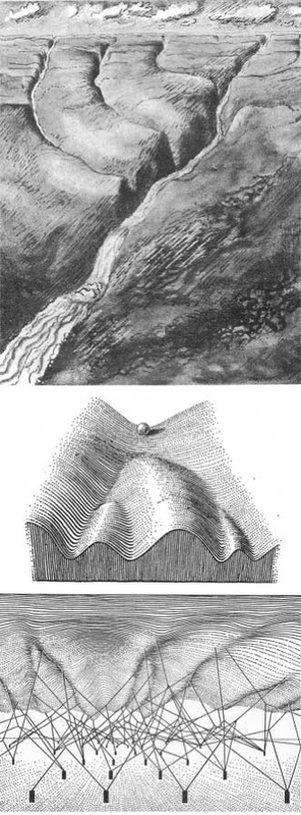

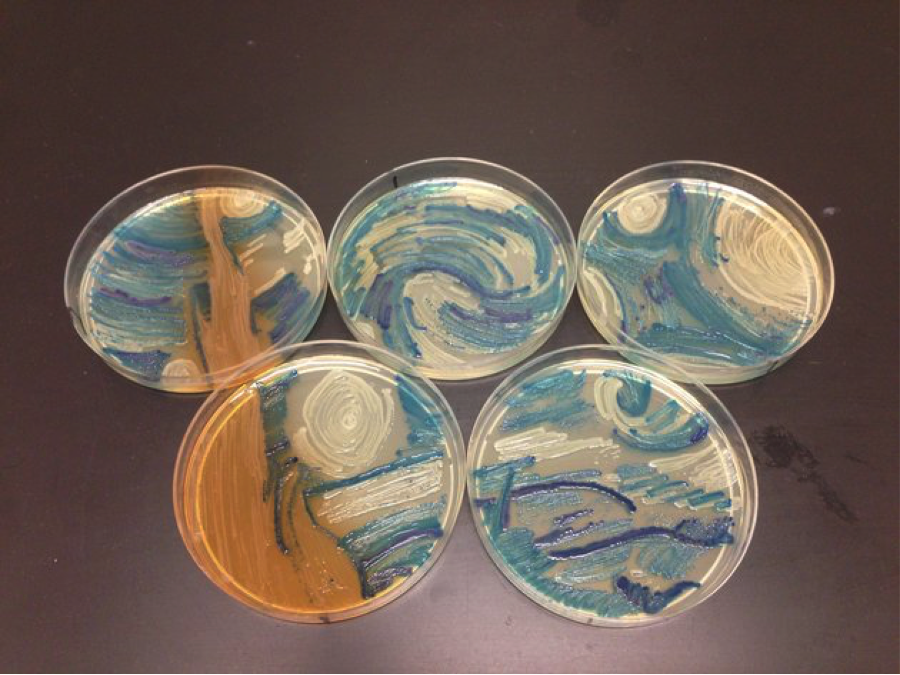

The Many Links between Art and Science: Rethinking Representation, Visualization, and Function

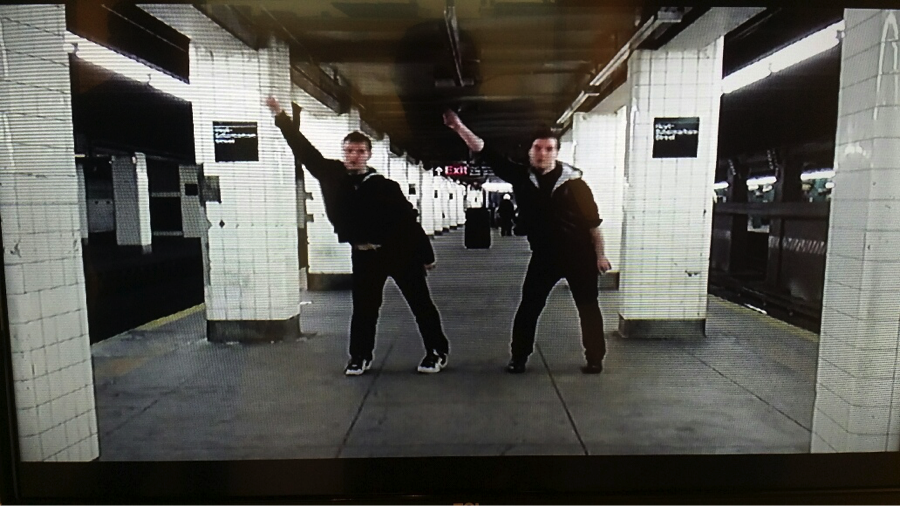

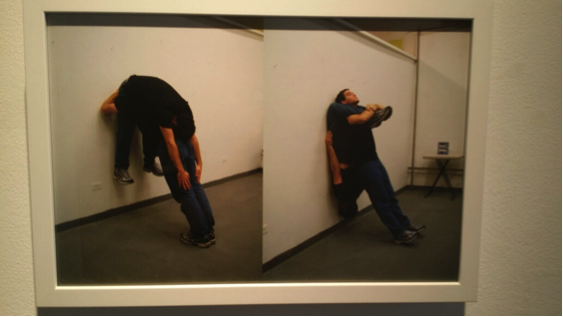

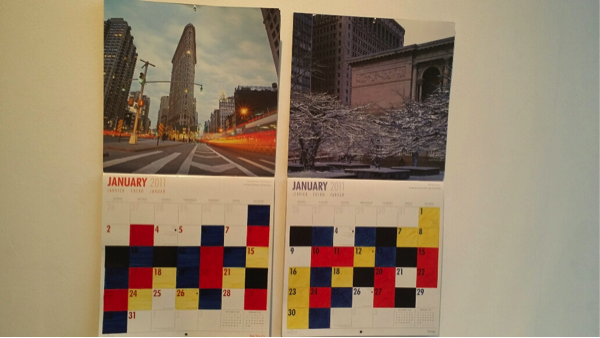

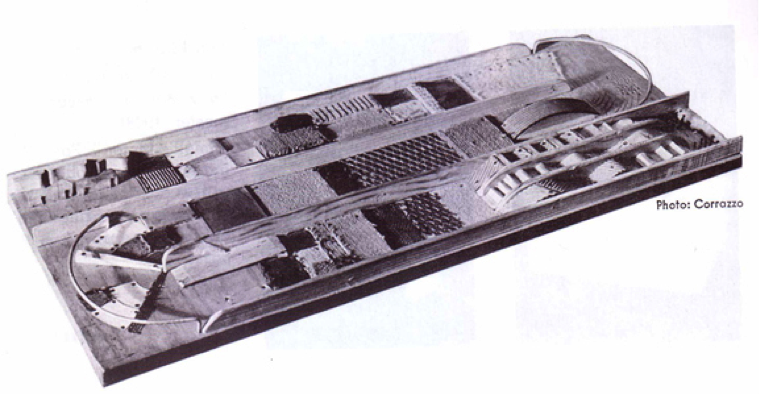

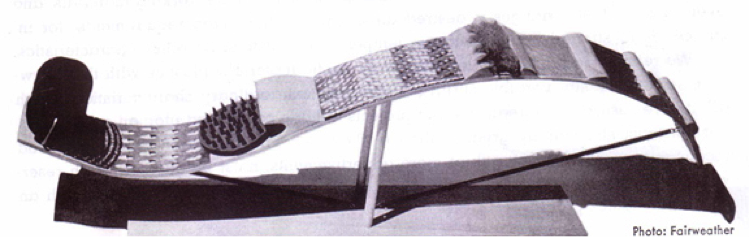

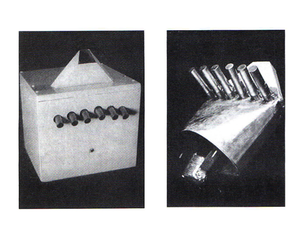

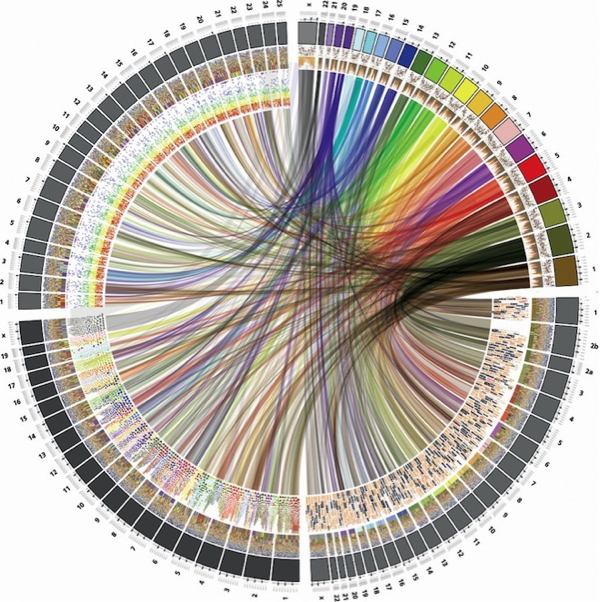

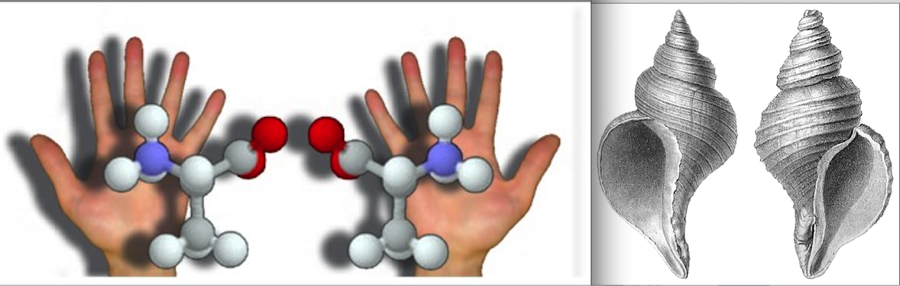

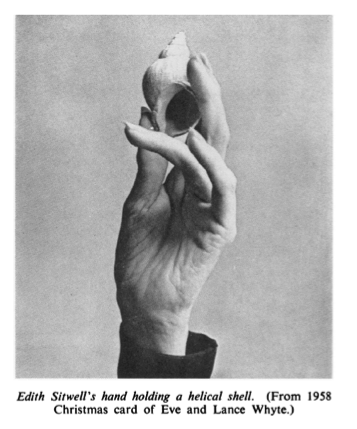

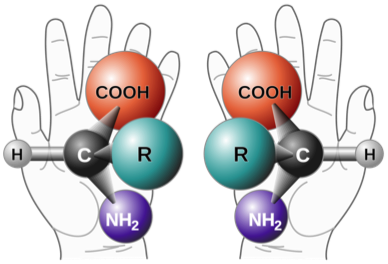

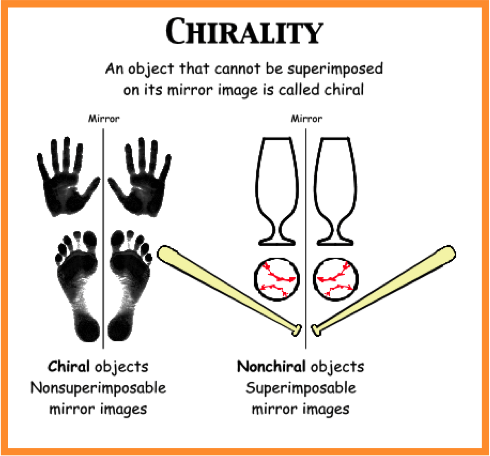

In Prop 1/Prop 2 we see a combination of dance, conceptual art, and minimalist sculpture – altogether making a work of performance art documented in a photograph. The Flemings perform slow, deliberative poses that mimic the rectilinear shapes of 1960s minimalist sculpture. Psychic Color Calendars is a conceptual piece based on telepathy. While living separately, one in New York the other in Chicago, the brothers wanted to test their telepathic skills, each coloring a square daily to see if their minds were in sync. The experiment shows they are not telepathic, with only the 4th and 20th of January syncing up color-wise. Trent Straughan, Eyes in the Back of Your Head, interactive software installation, two cameras, projector, and computer, 2015 Trent Straughan is a frontend software developer by day and an artist by life. His degree in graphic design has served him well! Eyes in the Back of Your Head is a work without an object; it is experiential and uses technology to exteriorize the senses and putative mind. Viewers stand at a specifically designated place centered between two cameras, while looking up at their projection on the wall. They see a live feed of their front, then back, then front, and then back again – indefinitely ad infinitum. The piece plays out the scientific concept of chirality as a live perceptual event facilitated by technologies of computation, surveillance, and projection. I draw connections between Straughan’s piece and Bruce Nauman’s Live Taped Video Corridor Piece (1970), Dan Graham’s time delay rooms from the 1970s, and Les Levine’s television sculpture from the late 1960s.  Jeff Gibbons, Beeper, 50 pounds of aging Appalachian clay, bucket, pillow case, unfired clay potato, 17” x 12” x 12”, 2015 Jeff Gibbons, Beeper, 50 pounds of aging Appalachian clay, bucket, pillow case, unfired clay potato, 17” x 12” x 12”, 2015 Gibbons’ Beeper takes on chirality by way of conceptual art – that is, through the language of fiction. The potato sitting atop a closed bucket is ersatz: it is made from clay, a mound of which sits inside. It is the mirror image – a chiral form – of an actual potato, about which Gibbons writes in a novel based on a character that is his mirror image living in a mirror world. Resonating with the work of Arthur C. Clarke and P.K. Dick, Gibbons brings chirality to the language of fiction writing and materializes ideas from his book. Another exciting idea for me here is the way in which chirality becomes adjacent to Jean Baudrillard’s idea of the simulacrum – all by way of Gibbons’ inventive touch. Ellen Levy is an artist engaged in neuroscientific research. She makes experiential mixed-media installations and writes about complex systems. These images combine analog and digital processes in the creation of swirling alter-worlds where the landscape becomes ocular and in automotive motion. They are experiential in that, according to Levy, “these works call for the viewer to perform mental rotations.” We see highway infrastructure shooting through the anatomical structures of the eye. In her own words, “the freeway interchange is visually mimicked in these works by the superimposition of retinal circuitry over it, including the crossover of visual signals at the chiasma.” I think here once again of the writing of Arthur C. Clarke, in particular the tubular megastructure in outerspace that is at the center of the novel Rama, which further connects us to the “alien megastructure 1400 light-years away” that was in the news last week. Luke Harnden, Dark Eyes, mirror, wood, fabric, 23"x17" 2015 Luke Harnden’s Dark Eyes is equal parts painting, sculpture, and experience. It hangs on the wall like a painting, must be interacted with like a sculpture, and offers a singular experience for each person. Harnden has wrapped nylon interfacing material used in quotidian sewing around a mirror to create a subtle moiré effect. Upon approaching the mirror, one sees black dots at the center of one’s eyes. The piece creates a vertigo of cognitive consciousness and is the great grandchild of the sci-art perceptually based work of Op Art and New Tendencies artists form the 1960s.  Steven J. Oscherwitz, Untitled Drawing, rolled pitt graphite on handmade twinrocker paper, 22” X 30”, 2010 Steven J. Oscherwitz, Untitled Drawing, rolled pitt graphite on handmade twinrocker paper, 22” X 30”, 2010 Steven J. Oscherwitz’s untitled drawing looks like two worlds mirrored while also overlapping. What I really love about Oscherwitz’s drawing is that it was not intended to be an example of chirality. He is adamant that his research in genetics and physics is not consciously present in any of his drawings. But scientific concepts seem to be there unconsciously as this drawing looks like a representation of chirality as well as the physics-based concept of “complementarity,” which is the idea that objects have complementary properties which cannot be measured accurately at the same time. While complementarity is not chirality, it is, like Baudrillard’s simulacrum, semantically connected in that it is a scientific idea about difference within similarity. It is also a term that showed up in one of the many e-mails Oscherwitz and I exchanged leading up to Chirality: Defiant Mirror Images. Dave & Charissa's Update: Gut Instinct, Epigenetics, or Biocomputation? Curating an On-Line Exhibition Last week, we had an exciting discussion about the possibility of co-curating an on-line exhibition. Here are three possible themes for on-line exhibitions: Gut Instinct “Gut Instinct” would be an exhibition about the brain-gut axis, microbiota, and the microbiome. Microbes are all over us. Single-celled organisms cover our skin. They inhabit our mouth and nose and ears. Our gut is full of millions of bacteria. In fact, microbiologists have estimated that the number of bacterial cells in and on us exceeds the number of actual human cells by a factor of 10 to 1. Collectively, these microbial partners are called our “microbiota” and their collective genome is called the “microbiome.” With recent advances in DNA sequencing and analysis, microbiologists have become better able to identify these partners of ours and determine how they affect our health. In fact, the National Institutes of Health began the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) in 2008 as a way of learning more about our microbiota. Researchers from various institutions have received funding from this project to investigate how microbes affect our general well-being. The proper functioning of the human body – wellness in its entirety, including weight, mood, and our ability to fend off disease – depends on a symbiotic relationship with the microbiota in and on our body. In fact, their genes help make our genes work. While there are infinitely interesting qualities about the microbiome, Charissa is most fascinated by the relationship between the brain, mood, and the gut – how the three work in concert to make one feel happy, or otherwise. Happiness depends in part on the well being of the microbiota of your tummy. Here we are once again confronted with holism: the brain and body are one. Works of art might take on this aspect of holism, showing how we think and feel across the body and senses, through smell, sound, and taste – rather than just sight. Charissa’s all time hero László Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian artist, philosopher of aesthetics, and teacher at the Bauhaus, the German school of design, was a holistic thinker. He had his students develop the full gamut of the senses in their training to become artists. These are projects – tactile-o-meters and a smell-o-meter – from his classes in the first half of the twentieth century.  Drawings by John Piper of Conrad Waddington’s “epigenetic landscape,” from The Strategy of the Genes (1957). Drawings by John Piper of Conrad Waddington’s “epigenetic landscape,” from The Strategy of the Genes (1957). Epigenetics An exhibition on “epigenetics” would also be about art that is holistic – that takes full account of the environment influencing gene expression. The prefix of “epigenetic” comes from the Greek “epi” meaning upon, near to, or in addition, so in the most literal sense epigenetics describes all of the forces, from within the cellular membrane to the atmosphere of the planet, which act on the genome giving shape to phenotypic expression. Geneticists typically use the term epigenetics to refer to DNA modifications that affect the structure of our DNA, which, in turn, affects gene expression. For example, certain bases in the DNA can be methylated. A –CH3 group is added to specific bases. With this epigenetic modification (a change upon, or near to the DNA), the sequence of bases in the DNA has not changed. The modification, however, may alter the overall structure of the DNA. This structural change, in turn, may make it more or less likely that a given gene will be expressed. Bottom line – two individuals could have different appearances, even though their DNA sequences were identical. These modifications can be inherited. They also can be caused by environmental factors. Recent research suggests that queen bees and worker bees in a hive differ not because they have different DNA (their DNA is identical), but because the larvae of the developing queen and worker bees are fed differ material. The diet of queen bee larvae affects gene expression by epigenetic means. Embryologist and geneticist Conrad Waddington hired his friend the Welsh painter John Piper to make renderings of the “epigenetic landscape,” a series of images that visualize the changing trajectory of cell potency – the way a cell differentiates into other cell types and functions. Art engaging a theme of epigenetics might deal with biological materials (it might be actual bioart), bear themes of environmental change or catastrophe, or visualize through painting and drawing how cells function. Biocomputation The field of biocomputation is one of the many exciting frontiers of biology. In short, it is an interdisciplinary field in which big data plays a central role. Since the 1980s, our ability to sequence DNA has improved dramatically. Today, we can sequence DNA more quickly, and more cheaply, than we could even five years ago. And the processes continue to become faster and less expensive. As a result, more and more DNA is being sequenced. In 1995, researchers for the first time published the entire genome of a living organism, the bacterium Haemophilus influenza, which has a genome of roughly 1.8 million bases. In 2004, the entire sequence of the human genome, all 3 billion bases, was published. Today, the entire genomes of over a thousand of organisms have been published. What do we do with all of that data? Scientists use software to understand biology. The growing fields of genomics and bioinformatics involve software designed to analyze and compare the vast amounts of DNA sequence data that are being generated daily. These analyses are providing exciting insight into the relationships between organisms and their evolutionary histories. Works of art engaging data visualization or synthetic biology might come to play in an exhibition on-line about biocomputation.

|

GROUP THREEDave Wessner

Charissa Terranova

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed