Dave's update:

Extending the Conversation As we approach the end of The Bridge virtual residency program organized by the SciArt Center of New York, I am sure that all three pairs of participants are finalizing their projects. Charissa and I are. We are excited to soon present Gut Instinct, our virtual exhibition focused on the gut microbiome, to the people attending the SciArt Center symposium in February and to a wider online audience. It will be fun for Charissa and me to talk about what we have learned from each other. It will be interesting to hear about the experiences of the other participants. But, at least for me, the impending end of our residency raises a new question. What comes next? As stated on the SciArt Center website, The Bridge virtual residency program was designed, "with the ultimate goal of bridging the gulf between the sciences and the creative humanities." Certainly, that noble goal cannot be fully achieved within a four month period of time. So what comes next? How do the collaborations begun during the residency continue? Just a few days ago, Charissa and I received a partial answer to this question. We have been invited to present our work at Critical Juncture, a conference being held in April, 2016 at Emory University. This conference is designed to explore the intersections of race, gender, and disability, and the specific theme of the 2016 conference is "Representations of the Body." During our presentation at this conference, we will share with a new audience how scientists and artists view the gut microbiome. More importantly, we will share with the participants how each of us has benefited from our interdisciplinary collaboration. In what ways will our collaboration evolve after the Critical Juncture conference? Only time will tell. For now, at least, we know what comes next.

Dave & Charissa's Update:

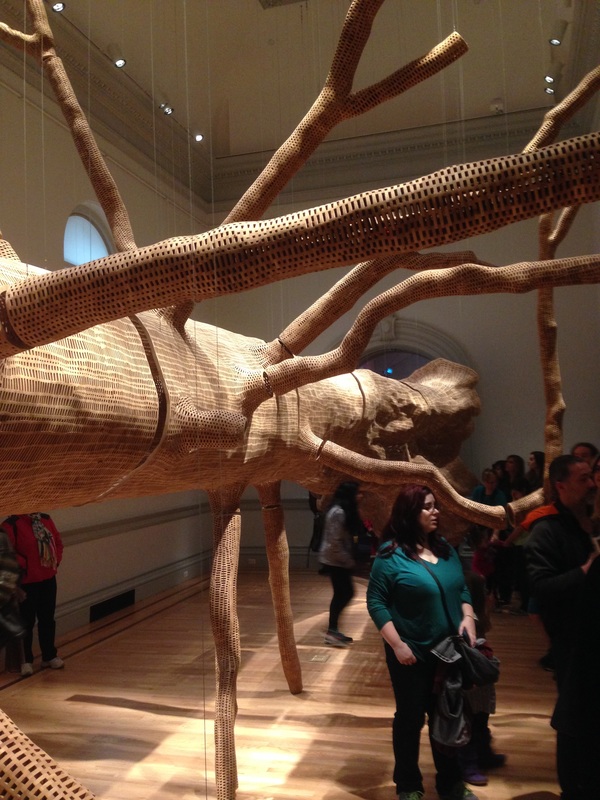

Gut Instinct: Art, Design, and the Microbiome an exhibition curated by Charissa N. Terranova and David R. Wessner During this past week, we continued to flesh out ideas for our online exhibition on the microbiome and its effects on human behavior. Most importantly, we drafted a curators’ statement that we will send to potential contributors to our exhibition. We are anxious to see the responses that we get. Here is our curators’ statement: The digestive systems of mammals are brimming with internal dwellers. Our guts are teeming with billions of microbes! Yet, it usually is a happy coexistence. We live in a state of mutual symbiosis with these inhabitants: in an alimentary feedback loop, we nurture them and they nurture us. While we provide a hospitable environment in which they can live, they are necessary for our holistic well-being. Various bacteria aid in the digestion of the food we eat. Bacteria like Escherichia coli produce vitamin K and B-complex vitamins for us. Increasing evidence indicates that the microbes in us may affect the functioning of our immune system and our mental health. The microbiota (the actual bacteria) and the microbiome (their DNA) clearly contribute to who we are. Gut Instinct: Art, Design, and the Microbiome will gather works by artists, architects, and scientists to give real and metaphorical shape to the human microbiome. Art theorist and critic Charissa Terranova and microbiologist Dave Wessner have teamed up to curate an online exhibition in particular on the brain-gut axis: how the bacteria in the gut affects mood. In parsing this head-stomach federation, Terranova and Wessner will show how rational thinking is connected to the intestines. They will reveal that consciousness and mind are seated in the brain as well as the GI tract. By connection, ratiocination unfolds across the body and is made possible by a full battery of the senses. Understanding “mind” in terms of the “gut-brain axis” shows how consciousness is more than quiet brainfed rumination: putative mind is rooted in the behavior of our gut bacteria as well. Mind is thus a matter of seeing, smelling, and tasting as well – anything that brings our gut-brain axis to a joyful equilibrium. That said, the exhibition will “visualize” the microbiome both scientifically and aesthetically. Here, Terranova and Wessner will deploy “visualization” in the most capacious sense of the term, as it describes scientific imagery as well as artistic interpretations of the scientific concepts, in this instance the microbiome, microbiota, and the brain-gut axis, i.e. gut bacteria and the cybernetic connections between the brain and intestinal tract. The show will include vibrant and colorful imagery of the microbiota in action, experimental uses of synthetic biology in architectural design, and curious and mind-opening microbiomic extrapolations by new media artists. The art in this exhibition will dwell on science, technology, art, design, and a full array of senses. |

GROUP THREEDave Wessner

Charissa Terranova

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed