|

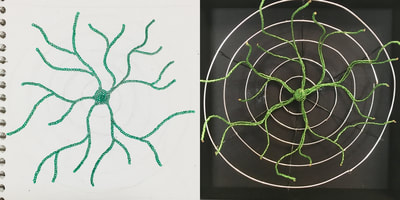

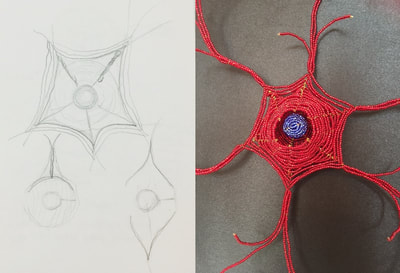

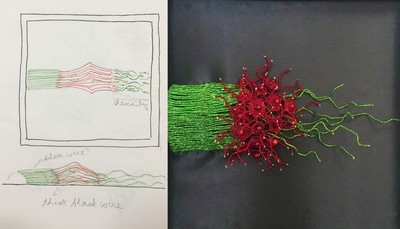

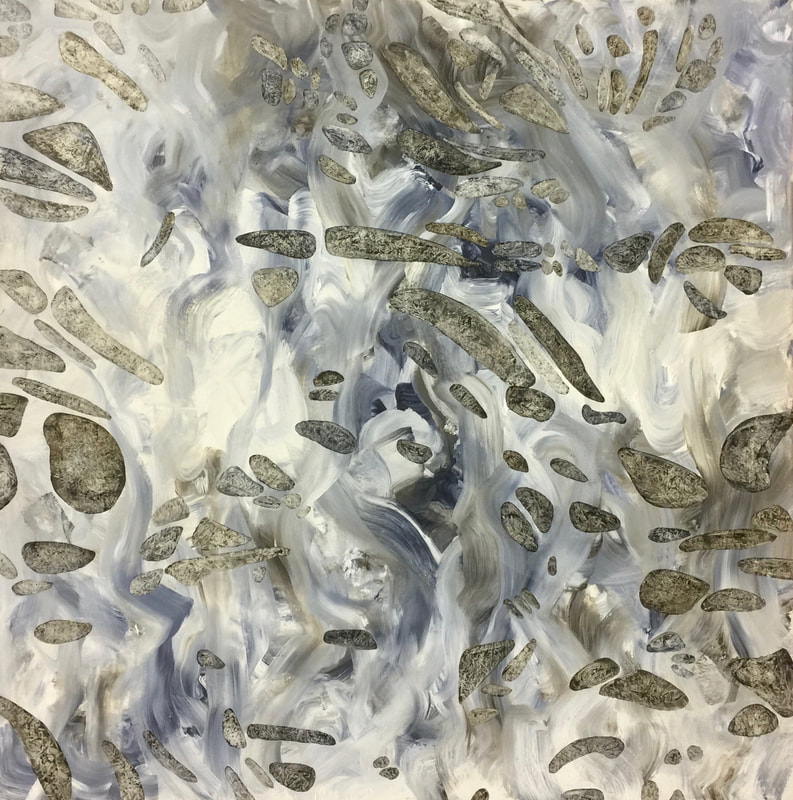

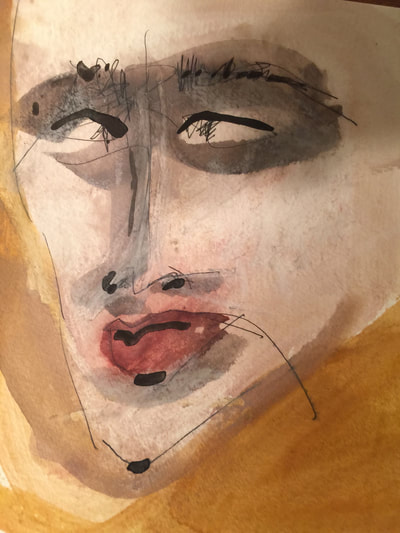

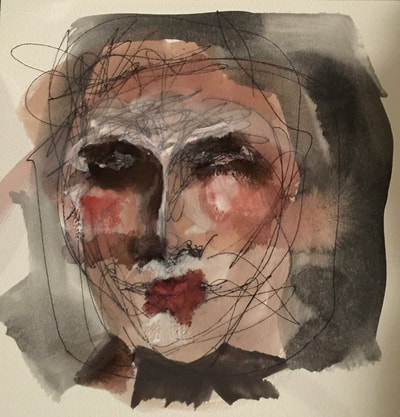

Yana Over the last couple of weeks, Darcy and I have been discussing the parallel aspects that are present in the daily lives of artists and scientists. One topic that has repeatedly come up is the comparison scientists’ lab notebooks and artists’ sketchbooks. In both professions, these records serve as a place to document methods, results and progress over time. They provide a framework for keeping track of what has been done and what has or hasn’t worked. Thereby, in theory, they should provide a space where we could not only gather data, but also brainstorm ideas; thereby allowing us to trace the evolution of our thinking process over time. However, this is where things begin to diverge. Several years ago I came across a wonderful article by Beth Schachter, a science communications consultant who taught scientific writing in my graduate school. In it, Beth talks about the “dry” aspects of a typical lab notebook, where scientists only record solid facts, observations and some common sense conclusions. She questions how this practice deprives us of the true potential of using a notebook as a creative play space for generating ideas, making connections and coming up with truly novel hypotheses. Unfortunately, lab notebooks are considered to be legal documents, which makes lab notebook keeping a dry and un-gratifying process. In following the rules, you are expected to only record solid data and factual statements that could be used in court if necessary. Therefore, scientists are actually strongly discouraged from writing any personal interpretations in their notebooks, as these may lead to more disputes. Compare this to an artist’s sketchbook, which provides complete freedom of experimentation with different concepts, which may never be seen by anyone but the artist, if he/she so chooses. Here, the notebook is used at an earlier, more “hypothetical” stage to try out different ideas and look at potential outcomes, rather than recording observed results. It is more akin to a personal journal, allowing for risks and tracing the artist’s self-discovery over time. This makes it a much more personal space that an artist may view as private. And of course, the artist’s sketchbook is much more visual, rather than focused on writing. People are known to respond differently to different forms of communication. Some people learn better through listening, reading or writing down information. I believe that I belong to the group of people who respond best to visual methods of presentation. A couple years ago, I found myself struggling with holding multiple pieces of information about my research project in my head. I began to draw diagrams and jot down thoughts on potential connections between findings in a separate journal. I tried to distill my copious note taking at meetings to the essence of the take home messages. It allowed me more freedom to brainstorm and free-associate between what appeared to be separate, random findings by drawing multiple lines between them. As a result, it allowed me to come up with my own version of what one of my colleagues liked to jokingly referred to as The Theory of Everything. In turn, that allowed me to communicate my working hypothesis to my colleagues better, proving the usefulness of a more creative approach to notebook keeping. As a final example, this summer I was approached by a curator, who was more interested in seeing my sketches than my final artworks. I would not have expected such a request. As I wrote in my second post (below), I only use my sketchbook to jot down the essence of an idea and the physical methods of executing it. But, I guess if an artist’s sketchbook truly serves as their playground rather than a laundry list, it also deserves to be seen. Darcy After an interesting Skype call with Yana and Kate my brain is buzzing with ideas. We talked about the legal constraints of lab books for scientific purposes versus the freedom and consequent privacy of artists’ sketchbooks. This led into other questions we have discussed previously about the role of imagery in science or art and the importance of visual material for clarity, accessibility, aesthetics, engagement and persuasion. All of these aspects of visual “information” I hope to think and write about at some point. Since Yana and I decided to use this conversation as a jumping off point for our individual blogs... let’s see what happens. As I leaf through my sketchbook, looking for insights, I keep returning to the idea of sketchbooks as the private realm of an artist. Sketchbook images and their role in the artistic process are very different from exhibited artwork that is meant to be responded to by the viewing public. Yana pointed out that labbooks are part of the public record of scientific research and in that way have legal and practical constraints and requirements. I am sure that this is also an interesting window into the differences between scientific and artistic inquiry. My paintings are finished works that have a fairly well defined process and are meant to be displayed in a public setting such as Stillness. My larger paintings and drawings are more purposeful than sketchbook images because they culminate from a number of ideas and often even merge different images together. Even when they are fast and expressive, like Machine below, my paintings are based on lots of experimentation in my sketchbook first. At my last art show, a number of people asked about my sketchbook work of faces that I sometimes post on Instagram (darcyelisejohnson). I do not develop these drawings into public work because they are a spontaneous attempt to capture personal feelings and expressions as an insight into the human psyche. Because of the transience of mood and emotion, these drawings are done intensively and quickly. The images pass away as quickly as they come. They are difficult to translate onto a large ground while maintaining their freshness and purpose.

There is likely another reason that I do not exhibit or develop these images. They are deeply personal and somewhat raw. Some artists use that type of imagery to evoke empathy and curiosity about the human condition. For me, the two sides of my art reveal the two sides of me. The thoughtful, abstract thinker that keeps emotion at bay while harnessing its passion for newness and discovery. The other side reveals a troubling emotional life that I also have to control. I suffer from clinical depression that began in my teens and set my life on its trajectory. So, I am attracted to science because it requires that we recognize and set aside some of our less objective experiences and rely on the quantifiable, systematic observations and analysis. Art making allows both sides of my personal experience a voice... albeit at times, a very private voice, in my sketchbook.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |